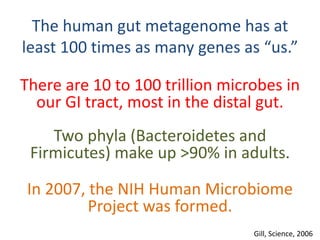

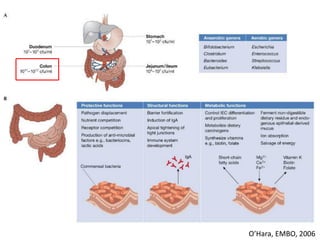

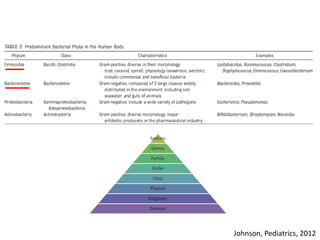

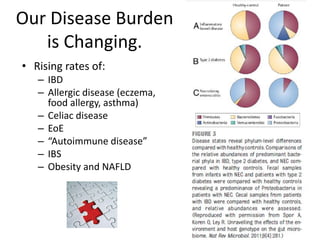

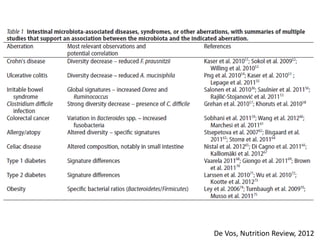

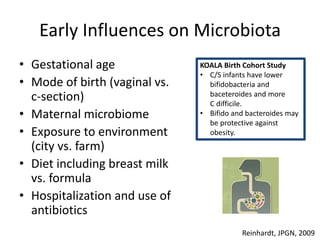

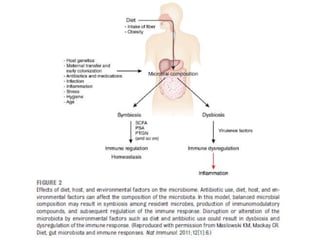

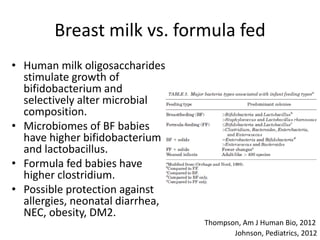

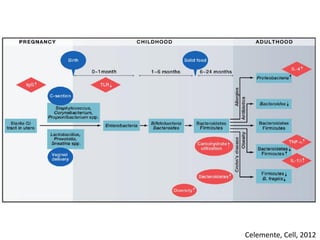

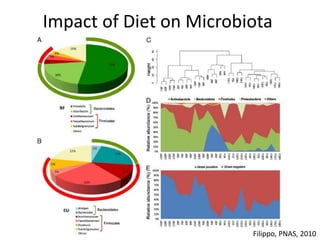

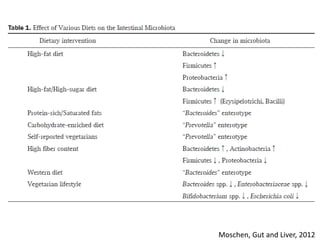

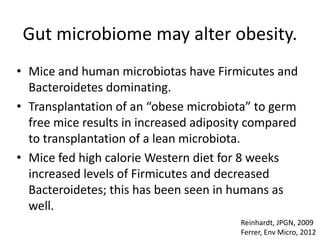

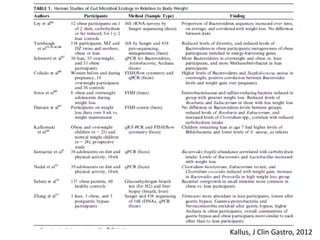

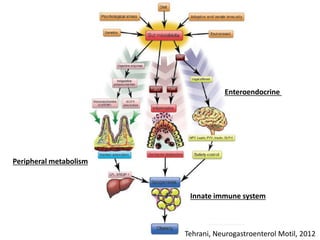

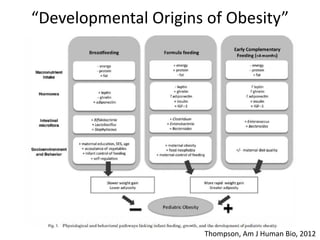

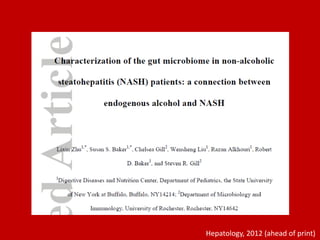

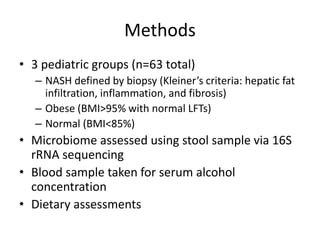

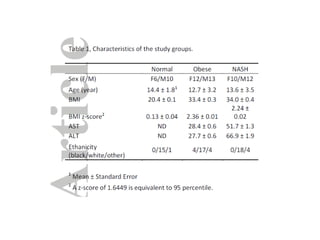

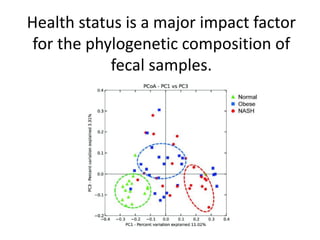

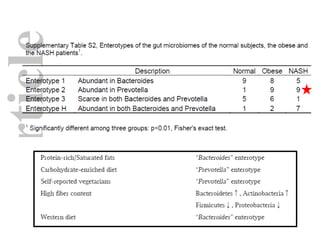

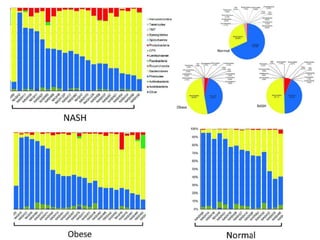

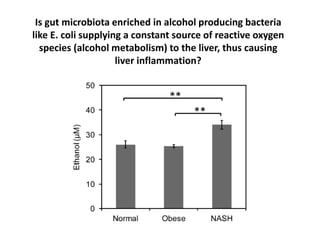

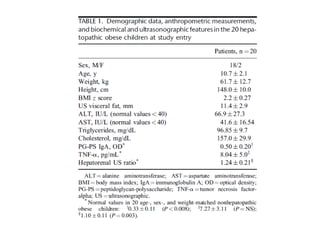

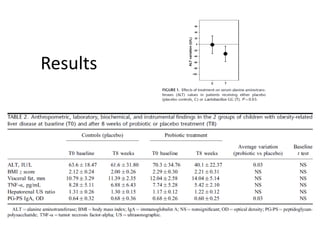

The document summarizes research on the gut microbiome and its relationship to obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). It reviews how the microbiome is influenced by factors from birth and can impact disease risk. Studies show differences in microbiome composition between obese, normal weight, and NAFLD patients, with NAFLD patients having higher levels of Escherichia bacteria that can produce alcohol. A pilot study found that treating pediatric NAFLD patients with the probiotic Lactobacillus GG for 8 weeks improved liver enzymes regardless of weight changes. Further research is still needed to fully understand the mechanisms and potential microbiome-based therapies.