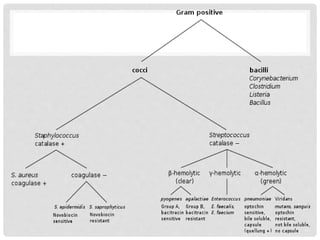

This document discusses gram positive sepsis and toxic shock syndrome. It begins by differentiating between gram positive and gram negative bacteria, noting that gram positive bacteria have a thicker peptidoglycan cell wall. It then discusses epidemiology of gram positive infections, evaluation and management of suspected sepsis, initial resuscitative therapy including IV fluids and antibiotics, monitoring response to therapy, identifying infection sources, and managing patients who fail or respond to initial therapy. It concludes by describing toxic shock syndrome caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

![EPIDEMIOLOGY

• Bloodstream infection mortality rates have increased by

78% in just two decades[1].

• Gram-positive organisms have a highly variable growth

and resistance patterns.

• The SCOPE project (Surveillance and Control of

Pathogens of Epidemiologic Importance) found that

gram-positive organisms in those with an underlying

malignancy accounted for 62% of all bloodstream

infections in 1995 and for 76% in 2000 while gram-

negative organisms accounted for 22% and 14% of

infections for these year.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/grampositivesepsis-200221084925/85/Gram-positive-sepsis-6-320.jpg)

![• Choosing a regimen — The choice of antimicrobials

can be complex and should consider the patient's history

(eg, recent antibiotics received, previous organisms),

comorbidities (eg, diabetes, organ failures), immune

defects (eg, human immune deficiency virus), clinical

context (eg, community- or hospital-acquired), suspected

site of infection, presence of invasive devices, Gram

stain data, and local prevalence and resistance patterns

[46-50].

• antimicrobial choice should be tailored to each

individual.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/grampositivesepsis-200221084925/85/Gram-positive-sepsis-17-320.jpg)

![• Methicillin-resistant S. aureus – There is growing recognition

that methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is a cause of

sepsis not only in hospitalized patients, but also in community

dwelling individuals without recent hospitalization [52,53]. For

these reasons, we suggest empiric

intravenous vancomycin (adjusted for renal function) be

added to empiric regimens, particularly in those with shock or

those at risk for MRSA. Potential alternative agents to

vancomycin (eg, daptomycin for non-pulmonary

MRSA, linezolid) should be considered for patients with

refractory or virulent MRSA, or with a contraindication to

vancomycin](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/grampositivesepsis-200221084925/85/Gram-positive-sepsis-19-320.jpg)

![DE-ESCALATION FLUIDS

• Patients who respond to therapy (ie, clinical hemodynamic

and laboratory targets are met; usually hours to days) should

have the rate of fluid administration reduced or stopped,

vasopressor support weaned, and, if necessary, diuretics

administered.

• While early fluid therapy is appropriate in sepsis, fluids may

be unhelpful or harmful when the circulation is no longer fluid

responsive.

• Careful and frequent monitoring is essential because patients

with sepsis may develop cardiogenic and noncardiogenic

pulmonary edema (ie, acute respiratory distress syndrome

[ARDS]).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/grampositivesepsis-200221084925/85/Gram-positive-sepsis-29-320.jpg)

![DIAGNOSIS

• The diagnosis of staphylococcal TSS is established based on

clinical and laboratory criteria

• Detection of S. aureus in culture is not required for the diagnosis of

staphylococcal TSS.

• S. aureus is recovered from blood cultures in approximately 5

percent of cases [24]; it is recovered from wound or mucosal sites in

80 to 90 percent of cases [62].

• According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC), a confirmed case is a case that meets the

following clinical criteria: fever, hypotension, diffuse erythroderma,

desquamation (unless the patient dies before desquamation can

occur), and involvement of at least three organ systems, with

cultures negative for alternative pathogens and serologic tests

negative for other conditions (if obtained). A patient who is missing

one of the above clinical criteria may be considered a probable

case.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/grampositivesepsis-200221084925/85/Gram-positive-sepsis-40-320.jpg)

![ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

• Empiric therapy — For empiric treatment of sepsis of unknown cause that

might represent staphylococcal TSS, we favor the following regimen (pending

culture results):

• ●Vancomycin (adults: 15 to 20 mg/kg/dose intravenously [IV] every 8 to 12

hours, not to exceed 2 g per dose; children: 60 mg/kg per day IV in four divided

doses)

• PLUS

• ●Clindamycin (adults: 900 mg IV every eight hours; children: 25 to 40 mg/kg IV

per day in three divided doses)

• PLUS one of the following:

• ●A combination drug containing a penicillin plus beta-lactamase inhibitor

(adults: piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5 g IV every six hours; children

300 mg/kg/day IV in four divided doses)

• ●A carbapenem (adults: imipenem 500 mg IV every six hours or meropenem 1 g

IV every eight hours; children: imipenem 15 to 25 mg/kg/dose every 6 hours

[maximum 4 g per day] or meropenem 25 mg/kg/dose every 8 hours)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/grampositivesepsis-200221084925/85/Gram-positive-sepsis-43-320.jpg)

![• In one case report of a 39-year-old man with HIV

infection and diffuse erythema of the arms and legs,

desquamation (of the arms, hands, feet, and eyebrows),

pharyngeal erythema, and a lesion that grew a TSST-1-

producing S. aureus, IVIG (200 mg/kg per day) was

administered for five days after failing antibiotic therapy;

symptoms subsequently resolved [63].

• ●In a retrospective study of patients with necrotizing

fasciitis and shock associated with group

A Streptococcus or S. aureus, adjunctive IVIG has no

apparent impact in mortality.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/grampositivesepsis-200221084925/85/Gram-positive-sepsis-47-320.jpg)