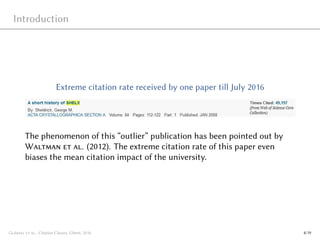

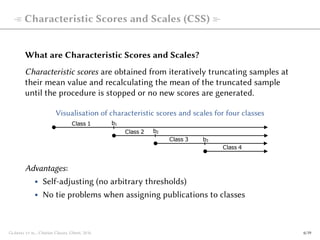

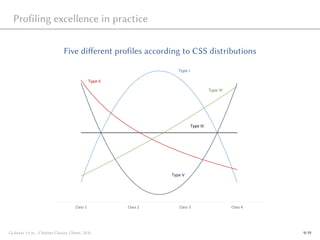

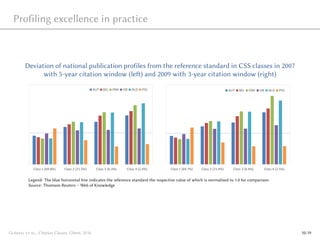

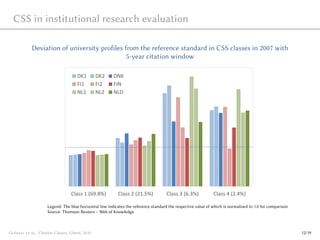

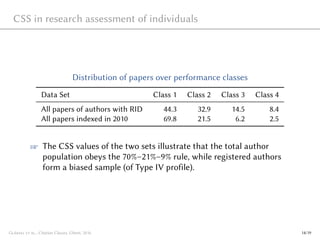

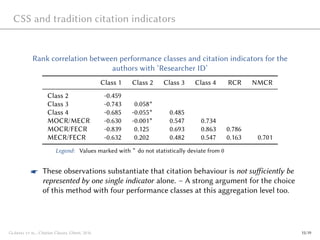

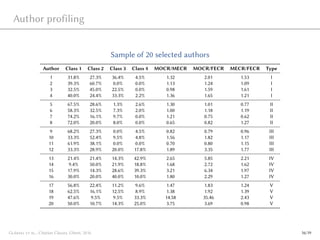

This document presents a novel method called Citation Classes (CSS) for classifying scientific publications based on their citation rates. CSS assigns publications to four performance classes in a self-adjusting manner without arbitrary thresholds. The document demonstrates how CSS can be applied at the level of institutions, countries, and individual researchers to generate detailed profiles of research performance. CSS was shown to be robust, flexible, and able to identify various types of highly-cited publications that traditional metrics cannot fully capture.