The document is a course sampler for a short course on engineering probability and visualization techniques using MATLAB, led by Dr. Ralph E. Morganstern. It covers fundamental probability concepts, including sample space, event space, and various representations such as matrix and tree diagrams, along with the application of DeMorgan's laws and counting principles. The Applied Technology Institute offers tailored training programs aimed at enhancing technical professionals' skills in a competitive marketplace.

![Fundamental Probability Concepts

• Probabilistic Interpretation of Random Experiments (P)

– Outcomes: sample space

– Events: collection of outcomes (set theoretic)

– Probability Measure: assign number “probability” P ε [0,1] to event

• Dfn#1-Sample Space (S): Fine-grained enumeration (atomic - parameters)

– List all possible outcomes of a random experiment

– ME - Mutually exclusive - Disjoint “atomic”

– CE - Collectively exhaustive - Covers all outcomes

• Dfn#2- Event Space (E): Coarse-grained enumeration (re-group into sets)

– ME & CE List of Events

S (all outcomes)

Atomic Outcomes

Events: A,B,C ME but not CE A D

(Disjoint by dfn)

Events: A,B,C ,D both ME & CE

C

B

14 INDEX

Discrete parameters uniquely define the coordinates of the Sample Space (S) and the collection of all

parameter coordinate values defines all the atomic outcomes. As such atomic outcomes are mutually

exclusive (ME) and collectively exhaustive (CE) and constitute a fundamental representation of the Sample

Space S.

By taking ranges of the parameters such as A, B, C, and D, one can define a more useful Event Space which

should consist of ME and CE events which cover all outcomes in S without overlap as shown in the figure.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-3-320.jpg)

![Fair Dice Event Space Representations

d2

• Coordinate Representation: 6

– Pair 6-sided dice 5

A: d1=3, d2 =arb.

4

– S={(d1,d2): d1,d2 = 1,2,…,6} 3

2 C: d1=d2

– 36 Outcomes Ordered pairs 1

d1

1 2 3 4 5 6

B: d1+d =7

• Matrix Representation: 1 [1 2 3 4 5 6] (1,1) (1,2) (1,3) (1,4) (1,5) (1,2 )

6

(2,1) (2,2) (2,3) (2,4) (2,5) (2,6)

– Cartesian Product: 2

3

= (3,1)

(3,2) (3,3) (3,4) (3,5) (3,6)

– {d1} x {d2} = d1 d2T 4 (4,1) (4,2) (4,3) (4,4) (4,5) (4,6)

(5,1) (5,2) (5,3) (5,4) (5,5) (5,6)

5

(6,1)

(6,2) (6,3) (6,4) (6,5) (6,6)

6

• Tree Representation: d2

d1 (1,1)

(1,2)

1 (1,3) 36 Outcomes

(1,4) Ordered Pairs

2 (1,5)

3 (1,6)

• Polynomial Generator for Sum Start

4

2 Dice 5 (6,1)

(6,2)

( x1 + x 2 + x3 + x 4 + x5 + x 6 ) 2 = 1x 2 + 2 x3 + 3 x 4 + 4 x5 + 5 x 6 + 6 x 7 6 (6,3)

(6,4)

Exponents represent + 5 x8 + 4 x9 + 3 x10 + 2 x11 + 1x12 (6,5)

(6,6)

6-sided die face numbers Exponents represent pair sums

Coefficients represent #ways 16

It is helpful to have simple visual representations of Sample and Event Spaces

For a pair of 6-sided dice, coordinate, matrix, and tree representations are all useful representations. Also

the polynomial generator for the sum of a pair of 6-sided dice immediately gives probabilities for each sum.

Squaring the polynomial (x1+x2+x3+x4+x5 +x6)2 yields a generator polynomial whose exponents represent

all possible sums for a pair of 6-sided dice S={2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12}and whose coefficients C=

{1,2,3,4,5,6,5,4,3,2,1} represent the number of ways each sum can occur. Dividing by the coefficients C by

the total #outcomes 62 = 36 yields the probability “distribution” for the pair of dice.

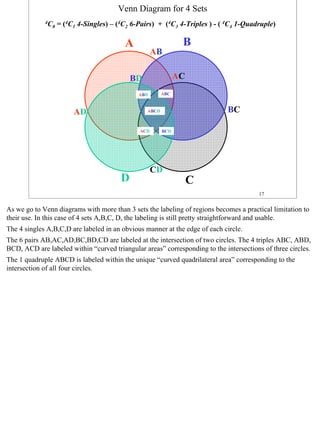

Venn diagrams for two or three events are useful; for example, the coordinate representation in the top

figure can be used to visualize the following events

A: {d1 = 3 and d2 = arbitrary, B= {d1 + d2 = 7}, and C= {d1 = d2}

Once we display these two events on the coordinate diagram their intersection properties are obvious, viz.,

both A & B and A & C intersect, albeit at different points, while B & C do not intersect (no point

corresponding to sum=7 and equal dice values). More than three intersecting sets, become problematic for

Venn diagrams as the advantage of visualization is muddled somewhat by the increasing number of

overlapping regions in theses cases (see next two slides).

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-4-320.jpg)

![Trivial Computation of Probabilities of Events

sum = d1 + d2

d2

Ex#1 Pair of Dice E1

S={(d1,d2): d1,d2 = 1,2,…,6} 6

12

5 11 E2

10

E1={(d1,d2): d1+d2 ¥ 10} 4 9

8

P(E1)=6/36=1/6 3 7

6

2 5

E2={(d1,d2): d1+ d2 = 7} 4

P(E2)=6/36=1/6 1 3

2 d1

1 2 3 4 5 6

Ex#2 Two Spins on Calibrated Wheel

S={(s1,s2): s1,s2 ε [0,1]} s2

E1={(s1,s2): s1+s2 ¥ 1.5}--> P(E1) = ----- =.52/2=1/8 1

1

E1

0.5 E3

E2={(s1,s2): s2 § .25} --> P(E2)=1(.25)/1=.25

E2

0 s1

E3={(s1,s2): s1= .85; s2= .35}--> P(E3)=0/1=0 0 0.5 1

20

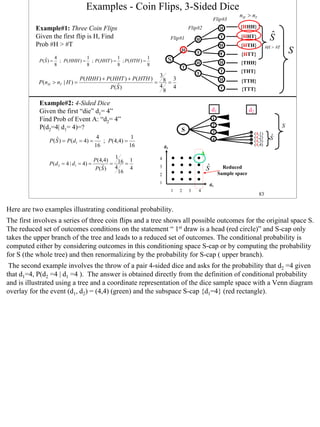

For equally likely atomic events the probability of any outcome Event is easily computed as the (#atomic

outcomes in Event)/(total # outcomes). For a pair of dice, the total # of outcomes is 6*6=36 and hence

simple counting of the # points in E /36 yields P(E), etc.

Two spins on a calibrated wheel [0, 1) can be represented by the unit square in the (s1 , s2)-plane and an

analogous calculation can be performed to obtain the probability for the event E by dividing the area

covered by the event by the area of the event space (“1”): P(E)= area(E)/ 1.

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-6-320.jpg)

![Man Hat Problem n =3 Tree/Table Counting

M#1 M#2 M#3 M.E. Match

Tree#1 Drw#1

Drw#2 Drw#3 Outcomes Outcomes

M#1 M#2 M#3 #Matches

E2 1

2 3 E3 {E1 E2 E3 } triple 1 2 3 3

1/2 Br#1

1

E1 1/2 3 2 c

{E1 E2 E3 }

c

single 1 3 2 1

1/3 1 1/2

1

1

3 E3 {E1c E2 c E3 } single 2 1 3 1

E1C Br#2

Start 1/3 2 1/2 1

1

c c

{E1 E2 E3 }

c

No-match 2 3 1 0

3

1/3 1/2

3 1

1

2 c c

{E1 E2 E3 }

c

No-match 3 1 2 0 Br#3

E1C

1/2

2 E2

1

1 c

{E1 E2 E3 }

c

single 3 2 1 1

P(Ei) = 1/3 2/6 2/6

From Table: From Tree: Connection: Matches & Events

Prob[0-matches]=2/6 Prob[0-matches]=1-Pr[E1 U E2 U E3]

Prob[1-matches]=3/6 Prob[Sgls]=P[E1]=P[E2]=P[E3]=1/3

=1-{Sum[Sngls]-Sum[Dbls]+Sum[Trpls]}

Prob[2-matches]=0/6=0 Prob[Dbls] = P[E1E2]=(1/3)(1/2)=1/6 =1-{3(1/3) -3(1/6)+1(1/6)}=2/6

Prob[3-matches]=1/6 Prob[Trpls] = P[E1E2E3]=(1/3)(1/2)=1/6

Alternate Trees Yield: P[E1E3]= P[E2E3]=1/6

75

This slide shows the complete the tree and associated table for the Man - Hat problem in which n=3 men

throw their hats in the center of a room and then randomly select a hat. The drawing order is fixed as

Man#1, Man#2, Man #3, and the 1st column of nodes labeled as circled 1, 2, 3 shows the event E1 in which

the Man#1draws his own hat, and the complementary event E1c i.e., Man#1 does not draw his own hat . The

2nd column of nodes corresponds to the remaining two hats in each branch shows the event E2 in which the

Man#2 draws his own hat; note that E2 has two contributions of 1/6 summing to 1/3. Similarly, the 3rd draw

results in the event E3 in two positions shown again summing to 1/3.

The tree yields ME & CE outcomes expressed as composite states such as {E1E2E3}, {E1E2cE3c, etc., or

equivalently in terms of the number of matches in the next column. The nodal sequence in the tree can be

translated into the table on the right which is analogous to the table we used on the previous slide. The

number of matches can be counted directly from the table as shown.

The lower half of the slide compares the “ # of matches” events with the “compound events” formed from

the “Ei”s{ no-matches, singles, pairs, and triples }. The connection between these two types of events is

based on the common event “no-matches,” i.e., the inclusion/exclusion expansion of the expression [1-

P(E1U E2U E3) ] in terms of singles doubles and triples yields P(0-matches).

75](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-15-320.jpg)

![Visualization of Joint, Conditional, & Total Probability

Binary Comm Signal - 2 Levels {0,1}

Binary Decision - {R0, R1}={(“0” rcvd , “1” rcvd} x = 0,1

Joint Probability

(Symmetric) 0 1 sent

P(0,R0) = P(R0,0) ovly

R1

“0” sent & R0 (“0” rcvd ) & y =R0 ,R1 R0 rcvd

R0 (“0” rcvd ) “0” sent

Conditional Probability

0R1

(Non-Symmetric) R0 ,R1 1R1

Joint

P(0|R0) ∫ P(R0|0) 0R0

1R0

“0” sent given R0 (“0” rcvd ) x = 0 ,1

P(0) = P(0, R0 ) + P(0, R1 ) P(R0 ) = P(R0 ,0) + P(R0 ,1)

R0 (“0” rcvd ) given “0” sent

Total Probability P(0) Total Probability P(R0)

sum up joint on R0,R1 sum across joint on 0,1

Conditional Probability P( R0 ,0) P( R0 ,0)

P ( R0 | 0) ≡ =

Requires Total Probability P ( 0) P( R0 ,0) + P( R0 ,1) Re-normalize

Joint Probability

P(0), P(R0), etc. P( R0 ,0) P ( R0 ,0)

P (0 | R0 ) ≡ =

P ( R0 ) P ( R0 ,0) + P ( R0 ,1)

88 INDEX

Another way to visualize the communication channel is in terms of an overlay of a Signal Plane divided

(equally) into “0”s and “1”s and a Detection Plane which characterizes how the “0”s and “1”s are detected

and is structured as shown so that when we overlay the two planes we obtain an Outcome Plane with four

distinct regions whose areas represent probabilities of the four product (joint) states { 0R0, 0R1, 1R0, 1R1}

(similar to the tree outputs).

In this representation the total probability of a “0” P(0) can be thought of as decomposed into two parts

summed vertically over the “0”-half of the bottom plane shown by the break arrow P(0) = P(0,R0) + P(0,R1)

[Note: summing on the “1”-half of the bottom plane yields P(1) = P(1,R0) + P(1,R1).]

Similarly the total probability P(R0) can be thought of as decomposed into two parts summed horizontally

over the “R0”-portion of the bottom plane shown by the break arrow P(R0) = P(R0,0) + P(R0,1); similarly

we have P(R1) = P(R1,0) + P(R1,1).

The Total Probability of a given state is obtained by performing such sums over all joint states.

88](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-19-320.jpg)

![Log-Odds Ratio - Add & Subtract Measurement Information

Note:

Revisit Binary Comm Channel P( R0 | 0) = .95 P ( R1 | 1) = .90 P(0)=.5

E = “1”

P( R1 | 0) = .05 P ( R0 | 1) = .10 P(1)=.5

Ec = “0”

Relation between P (1 | R1 ) P (1 | R1 ) e L1

L1 ≡ ln 1 − P(1 | R ) ⇒ e = 1 − P(1 | R ) ⇒

L1

P(1 | R1 ) =

L1 and P(1|R1) 1 1 1 + e L1

P(1 | R1 ) P (1) P ( R1 | 1) P(1) P( R1 | 1)

L1 ≡ ln 1 − P(1 | R ) = ln 1 − P(1) + ln 1 − P( R | 1) = ln P(0) + ln P ( R | 0)

1 1 1

≡ L0 ≡ ∆L1

P( R1 | 1)

Additive Meas Updates for L Lnew = Lold + ∆LR1 P (1)

P(0) ; ∆LR1 = ln P( R | 0)

Lold = ln

1

Updates

Meas#1: R1 Meas#2: R0 Alternate Meas#2: R1

.5 P( R0 | 1) .10 P( R1 |1)

Lold = ln = 0 ∆LR0 = ln .90

.5 P( R | 0) = ln .95

∆LR1 = ln = ln

0 P( R1 | 0) .05

.9 = −2.25129

∆LR1 = ln = +2.8903

.05 Lnew = Lold + ∆LR0 Lnew = Lold + ∆LR1

= 2.8903

= 2.8903 + (−2.25129) = .63901 = 2.8903 + 2.8903 = 5.7806

Lnew = 0 + 2.8903

e 2.8903 e.63901 e 5.7806

P(1 | R1 ) = = .947 P(1 | R1 R0 ) = = .655 P (1 | R1 R0 ) = = .997

1 + e 2.8903 1 + e.63901 1 + e 5.7806

96 INDEX

Revisiting the binary communication channel we now compute updates using the log odds ratio which are

additive updates. The update equation simply starts from the initial log odds ratio which is

Lold=ln[P(1)/P(1c)] =ln(.5/.5)=0 for the communication channel. There are two measurement types R1 and

R0 and each adds an increment ∆L determined by its measurement statistics, viz.,

R1: ∆LR1 =ln[(P(R1|1)/P(R1|1c)]=ln(.90/.05) = +2.8903 (positive “confirming”)

R0: ∆LR0 = ln[(P(R0|1)/P(R0|1c)]=ln(.10/.95)= -2.25129. (negative “refuting”)

The table illustrates how easy it is to accumulate the results of two measurements R1 followed by R0 by just

adding the two ∆Ls to obtain

Lnew= 0+2.8903-2.25129=.63901,

or alternately R1 followed by R1 to obtain

Lnew=0+2.8903+2.8903=5.7806.

These log odds ratios are converted to actual probabilities by computing P= eLnew / (1+ eLnew ) yielding .655

and .997 for the above two cases.

If we want to find the number of R1 measurements needed to give .99999 probability of “1” we need only

convert .99999 to an L =ln[(.99999)/(1-.99999)] =11.51 and divide the result by 2.8903 to find 3.98 so that

4 R1 measurements are sufficient.

96](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-20-320.jpg)

![Discrete Random Variables (RV) –Key Concepts

• Discrete RVs: A series of measurements of random events

• Characteristics: “Moments:” Mean and Std Deviation

• Prob Mass Fcn: (PMF), Joint, Marginal, Conditional PMFs

• Cumulative Distr Fcn: (CDF) i) Btwn 0 and 1, ii) Non-decreasing

• Independence of two RVs

• Transformations - Derived RVs

• Expected Values (for given PMF)

• Relationships Btwn two RVs: Correlations

• Common PMFs Table

• Applications of Common PMFs

• Sums & Convolution: Polynomial Multiplication

• Generating Function: Concept & Examples

122 INDEX

This slide gives a glossary of some of the key concepts involving random variables (RVs) which we shall

discuss in detail in this section. Physical phenomena are always subject to some random components so

that RVs must appear in any realistic model and hence their statistical properties provide a framework for

analysis of multiple experiments using the same model. These concepts provide the rich environment that

allows analysis of complex random systems with several RVs by defining the distributions associated with

their sums and transformations of these distributions inherent in the mathematical equations that are used to

model the system.

At any instant, a RV takes on a single random value and represents one sample from the underlying RV

distribution defined by its probability mass function (PMF). Often we need to know the probability for some

range of values of a RV and this is found by summing the individual probability values of the PMF; thus a

cumulative distribution function (CDF) is defined to handle such sums. The CDF formally characterizes the

discrete RV in terms of a quasi-continuous function that ranges between [0,1] and which has a unique

inverse.

Distributions can also be characterized by single numbers rather than PMFs or CDFs and this leads to

concepts of mean values, standard deviations, correlations between pairs of RVs and expected values.

There are a number of fundamental PMFs used to describe physical phenomena and these common PMFs

will be compared and illustrated through examples. Finally, the relationship between the sum of two RVs

and the concept of convolution and the generating function for RVs will be discussed.

122](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-21-320.jpg)

![Common PMFs and Properties -1

RV Name PMF Mean Variance

E[ X ] = ∑ x⋅ p

x = 0 ,1

X ( x) var( X ) = E[ X 2 ] − E[ X ]2

p X = 1 (success)

Bernoulli p X ( x) =

1 − p = q X = 0 (failure) E [ X 2 ] = 0 2 ⋅ (1 − p ) + 12 ⋅ p

1-Trial

E [ X ] = 0 ⋅ (1 − p ) + 1 ⋅ p = p

X=x succ.

= p var( X ) = p − p 2 = p (1 − p )

“0” or “1” x “Atomic” RV

successes = pq

0 1

p X (x)

Binomial n

p X ( x) = p x q n − x

x

n

n

n - Trials E[ X ] = ∑ x p x q n − x

6/16

5/16

var( X ) = npq

x = 0,1, n x=0 x

X=x Succ. 4/16

3/16

= np

How many Independent 2/1

6

1/16

succ “x” in Bernoulli Trials 0 x

“n” trials ? 0 12 3 4

p X (x)

Geometric p X ( x) = pq

x −1

x = 1,2, ∞

d ∞ x

1/2

E[ X ] = ∑ x ⋅ pq x −1 = p ∑q var( X ) =

q

X=x Trials 0 (otherwise) 7/16 dq x =1

6/16

x =1 p2

1- Success 5/16 d 1 +p 1

=p = =

dq 1 − q (1 − q) 2 p

4/16

How many One Sequence 3/16

trials “x” 2/16

1/16 As p decr. Expected num. trials

for “1” succ 0 x “x” for 1-succ must incr.

0 1 2 3 4 5 ... ∞

x − 1 r x − r

Negative x − 1 r −1 x − r E[ X ] = ∑ x ⋅

r − 1 p q

q

r − 1 p q ⋅ p

p X ( x) = var( X ) = r ⋅

Binomial

x=r

p2

succ. on

Geom RV = Neg Binom r

next trial =

X=x Trials ( r −1) succ. in ( x −1) trials

for r=1 succ. p

x = r , (r + 1), ( r + 2), ∞ As p decr. Expected num. trials

r- Successes

Many Sequences “x” for r-succ must incr.

137 INDEX

This table and one to follow compare some common probability distributions and explore their

fundamental properties and how they relate to one another. A brief description is given under the “RV

Name” column followed by the PMF formula and figure in col#2; formulas for the mean and variance are

shown in the last two columns.

The Bernoulli RV X answers the question “what is the result of a single Bernoulli trial?” It takes on

only two values, namely “1”=Success with probability p and “0”=Fail with probability q=1-p.

The Binomial RV “X” answers the question “how many successes X in n Bernoulli trials?” It takes on

values corresponding to the number of successes “X” in “n” independent Bernoulli trials; the sum RV

X=X1+ X2+ ...+Xn of n Bernoulli RVs has nCx tree paths for X=x successes yielding a pmf nCx px qn-x as

shown.

The Geometric RV X answers the question “how many Bernoulli trials X for 1 success?” It takes on

values from 1 to infinity and is the sum of n-1 failed Bernoulli trials followed by one successful trial; the

sum RV X=X1+ X2+ ...+Xn of n Bernoulli RVs has only one tree path with X= x trials yielding 1-success

and so has a pmf qx-1 p1 as shown.

The Negative Binomial RV X answers the question “how many Bernoulli trials X for r- successes?” It

takes on values from r to infinity and is the sum of n Geometric random variables; the sum RV X=G1+

G2+ ...+Gr of “r” Geometric RVs with probability pr-1 qx-r p1 and has x-1Cr-1 tree paths for X=x-1 trials

yielding (r-1)-successes followed by one final success and so has a pmf x-1Cr-1 pr-1 qx-r p1 with x = r, r+1,

... inf, as shown

137](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-23-320.jpg)

![Bernoulli/Binomial Tree Structures

RV Name PMF

p X = 1 (success)

Bernoulli p X ( x) = (q+p) x Prob

1-Trial 1 − p = q X = 0 (failure)

F

q 0 q

X=x succ. START

p

1 p

“0” or “1” x “Atomic” RV S

successes 0 1

Prob

Binomial 2 p X (x) x

p X ( x) = p x q 2 − x

2 - Trials x (q+p)2 F {FF} 0 q2 2C

1/2 q 0

x = 0,1, 2

X=x Succ. q

F

S {FS} 1 qp

p 2C

1/4

How many Independent START

q F {SF} 1 pq

1

succ “x” in Bernoulli Trials x

p S

{SS} 2 p2 2C

“2” trials ? p

S

2

0 1 2

(q+p)2 = q2 + 2pq + p2

= 2C0 p0 q2 + 2C1 p1 q1 + 2C2 p2 q0

138 INDEX

The RVs of the last slide are grouped in pairs {Bernoulli,Binomial} and {Geometric, Negative Binomial}

for a reason. The sum of many independent Bernoulli trials generates a Binomial distribution and similarly

the a sum of many independent Geometric trials generates the Negative Binomial distribution. This slide

and the next give a graphical construction of these trees for these two groups of paired distributions by

repeatedly applying the basic tree structure of the underlying Bernoulli or Geometric tree structure as

appropriate.

In the first panel we show the PMF properties for Bernoulli on the left and on the right we display

Bernoulli tree structure where the upper branch q=Pr{Fail] goes to the state X= 0 and the lower branch p =

Pr[Success] goes to the state X= 1.

In the second panel we show the PMF properties for a simple n=2 trial Binomial. The corresponding tree

structure for this Binomial is obtained by appending a second Bernoulli tree to each output node of the first

trial, thus yielding the 4 output states {{FF}, {FS}, {SF}, {SS}}. We see that there is 2C0 tree paths leading

to {FF} p0q2 , 2C1 tree paths leading to{FS} p1q1 , and 2C2 tree paths leading to {SS} p2q0 , which is

precisely as expected from the Binomial PMF for n=2.

This can be continued for n=3, 4, ... by repeatedly appending a Bernoulli tree to each new node. Further we

see that this structure for n=2 is represented algebraically by (q+p)2 inasmuch as the direct expansion gives

1=q2 + 2q1p1 +p2 ; expanding an expression corresponding to n Bernoulli trials (q+p)n obviously yields the

appropriate Binomial expansion for general exponent n.

Thus the Binomial is represented by the repetitive tree structure or by the repeated multiplication of the

algebraic structure 1=(q+p) by itself n-times to obtain 1n=(q+p)n .

138](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-24-320.jpg)

![Geometric/NegBinomial Tree Structures

RV Name PMF

p X (x)

Geometric

pq x −1 x = 1,2, 1/2

[(1-q)-1 p]

X=x Trials p X ( x) = 7/16

q

F

0 (otherwise) 6/16

p

1- Success 5/16 F S

4/16 q

How many 3/16 START p

trials “x” for One Infinite 2/16 S

“1” succ Sequence 1/16

p

0 x

0 1 2 3 4 5 ... S

Negative x − 1 2−1 x − 2 F

Binomial p X ( x) = p q ⋅ p [(1-q)-1 p ]2 q

2 − 1 succ. on q F

X=x Trials (2 −1)succ. in ( x −1) trials

next trial S p

S

2- Successes

x = 2,3, 4, ∞ q

F p

p

F S

S

p X (x) START

q

p q

F

1/4 S q F

p S p

3/16 S

S p

Many Infinite

1/8

Sequences S

1/16 F

q

0 x S

q F

0 1 2 3 4 5 ... p

S

p2 (1-q)-2 = p {1+(-2)1-3(-q)1 +[(-2)(-3)/2] 1-4(-q)2 +[(-2)(-3)(-4)/(2)(3)] 1-5(-q)3 + ...} p p

...} S

={ 1C p

1 + 2C

1 pq1 + 3C

1 p1 q2 + 4C1 p1 q3 + p

139 INDEX

This slide first gives a graphical construction of a Geometric tree from an infinite number of Bernoulli

trials and then shows how the Negative Binomial tree is the result of appending a Geometric tree to

itself in a manner similar to that of the last slide. In the first panel we repeat the PMF properties for

Geometric RV. On the right side of this panel we display Geometric tree structure whose branches end

in a single success. This tree has a Bernoulli trial appended to each failure node and is constructed from

an infinite number of Bernoulli trials. The 1st Bernoulli trial yields X=1 with p=Pr[Success] and this

ends the lower branch; its upper branch yields X=0 with q=Pr{Fail]; this failure node spawns a 2nd

Bernoulli trial which again leads to X=1 or X=0; this process continues indefinitely. It accurately

describes the probabilities for a single success in 1, 2, 3,... inf number of trials and is algebraically

represented by the expression 1=[(1-q)-1 p] which expands to [1 + q1 + q2 + q3 +....]*p corresponding to

exactly 0, 1, 2, 3,... “failures before a single success”

In the second panel we show the PMF properties for an r=2 Negative Binomial; on the right we display

the Negative Binomial tree structure obtained by applying the basic Geometric tree to each node

(infinite number) corresponding to a 1st success. This leads to a doubly infinite tree structure for the r=2

Negative Binomial which gives the number of trials X =x required for r=2 successes. We can verify the

first few terms in the Negative binomial expansion given under PMF in the lower panel using the tree.

This process may be extended to r=3, 4, ... successes by repeatedly applying the Geometric tree to each

success node. For n=2, direct expansion of the algebraic identity 12=[(1-q)-1 p]2 yields { 1C1 p + 2C1 pq1

+ 3C1 p1 q2 + 4C1 p1 q3 + ...}p in agreement with the n=2 Negative Binomial terms in the table. In an

analogous fashion expansion of 1r=[(1-q)-1 p]r yields results for the r-success Negative Binomial. Note

that the “Negative” modifier to Binomial is a natural designation in view of the (1-q)-1 term in the

algebraic structure.

139](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-25-320.jpg)

![Bernoulli, Geometric, Binomial & Negative Binomial PMFs

• Bernoulli RV as Probability “Indicator” for Outcomes of a Series of

Experiments representing a two different Event types, namely,

E1: “Success in 1 trial” X = Bernoulli RV Binomial b(k;n,p)

n = # trials , k = # successes

E2: “ N1 is #Trials for 1stsuccess“ N1 = Geometric RV K=# Succ

for n- trials

n n

K = ∑ Xi p K (k ) = p k q n − k

k

i =1

n

K = ∑ Xi

Bernoulli Bernoulli Process Sum n Indep. i =1

Single RV , Two Outcomes 1 Bernoulli trial for Bernoulli RVs “X” E ( K ) = µ K = np

Event E1 var( K ) = σ K = npq

2

p X = 1 (success)

p X ( x) = p X ( x) = p

1 − p = q X = 0 (failure)

Neg. Binomial bn(nr;r,p)

Sum r Indep.

1 = # trials , 0,1 = # successes Geometric RVs

Geometric Process nr = #trials for r successes

”N1”

E ( X ) = µ X = p ; var( X ) = σ X = 0

2

n1 Bernoulli trials for n − 1

pNr (nr ) = r p r q nr − r

Event E2 r −1

r

pN1 (n1 ) = p1q n1 −1 N r = ∑ ( N1 )i r

i =1 N r = ∑ ( N1 )i

i =1

1

E[ N r ] = µ N r = rE[ N1 ] = r

Nr =# Trials p

for r-Succ. q

var( N r ) = σ N r 2 = r var( N1 ) = r

p2

140

The Bernoulli RV “X” is the basic building block for other RVs ( “atomic” RV ) and has a PMF

distribution with only two outcomes X=1 with probability p and X=0 with probability q=1-p . We have seen

that n such Bernoulli variables when added yield a Binomial PMF {b(x;n,p), x=0,1,2,...,n} which gives the

“#successes “x” for “n” trials.

We have also seen that this Binomial PMF can be understood by repeatedly appending the Bernoulli tree

graph to each of its nodes (repeated independent trials) thereby constructing a tree with 2n outcomes

corresponding to the n Bernoulli trials, each with two possible outcomes.

Alternately, the Geometric PMF can be constructed by repeatedly appending a Bernoulli tree graph, but this

time only to the failure node, an infinite number of times, thereby constructing a tree with an infinite

number of outcomes all of which correspond to “x-1” failures and exactly 1 success for x=1,2, ...., inf.

Just as the Bernoulli tree graph is a building block for the Binomial tree graph, the infinite Geometric PMF

tree graph is a building block for the Negative Binomial. The Negative Binomial tree graph for r=2

successes is constructed by appending a Geometric tree graph to itself, but this time only to the success

nodes, resulting in a doubly infinite tree graph corresponding to exactly “x-1” failures and exactly 2

successes for x= 2,3 ...., inf. Repeating this process r-times yields the r-fold infinite tree graph

corresponding to exactly “x-1” failures and exactly r successes for x= r,r+1, ...., inf.

The mathematical transformations relating Bernoulli, Binomial,Geometric and Negative Binomial are

shown in this slide.

140](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-26-320.jpg)

![Common PMFs and Properties-2

RV Name PMF Mean Variance

E[ X ] = ∑ x⋅ p

x = 0 ,1

X ( x) var( X ) = E[ X 2 ] − E[ X ]2

"m-marked" "(N-m) = unmarked"

x from (n-x) from

Hyper- m ( N − n) m ( N − m)

m N − m E[ X ] = n ⋅ = n ⋅ p var( X ) = n ⋅ ( N − 1) ⋅ N ⋅ N

geometric x N

n−x ; x ≤ x ≤ x

X=x -succ pX ( x) = where p = m / N is the

N

min max

( N − n)

N= fixed pop "initial" probability of var( X ) = ⋅n⋅ p⋅q

n ( N − 1)

m= tagged 0 ; Otherwise drawing a marked item

n=test sampl m ∈ [1, N ] ; n ∈ [1, N ] ; ( N − m − n) ≤ x ≤ min(m, n)

w/o rplcemt PMF Derives from N m + ( N − m) m N − m m N − m m N − m m N − m

Binomial Identity = = + + + + +

n n 0 n 1 n −1 x n − x n 0

n≤m≤ N

Poisson ( a x / x !)

x = 0,1, 2, ∞

Trials p X ( x) = ea

E[ X ] = a var( X ) = a

0 Otherwise

X=x Succ

Limit of Binomial

a = lim(n ⋅ p) = λ ⋅ t = (aver. arrival rate)*time

n →∞

p →0

Zeta(Zipf)

( )

1 xs

p X ( x; s ) = ζ ( s) =

"ζ − term "

x = 1, 2, ; s >1 (

∞

E[ X ; s ] = ζ 1s ) ⋅ ∑ x⋅ 1s

x

(

∞

Var ( X ; s ) = ζ 1s ) ⋅ ∑ x2 ⋅ 1s − E[ X ; s]2

x =1

x

n - Trials ζ (s) x =1

X=x Succ.

0 Otherwise (

∞

= ζ 1s ) ⋅ ∑

1

= ζζ( s( −1)

s)

= ζ ζ( s(−)2) −

s ( ζ (s) )

ζ ( s −1) 2

x s −1

−1 x =1

( )

∞ ∞

ζ (1.5) ζ (2.5) 2

∑

x =1

= 1 ⇒ C = ∑ 1s = ζ 1s )

C

xs

x =1 x

(

E[ X ; s = 3.5] = ζζ( s( −1) = 1.191

Var ( X ; s = 3.5) = ζ (3.5) − ζ (3.5)

s)

= .856

Riemann Zeta Fcn ζ (s)

141 INDEX

This second part of the Common PMFs table shows the Hyper-geometric, Poisson and Riemman Zeta (or

Zipf ) PMFs

The Hyper-geometric RV “X” answers the question “how many successes (defectives) X are obtained

with n test samples (trials without replacement) from a production run (sample space) that contains m

defective and N-m working items?” X takes on values corresponding to the number of successes

(defectives) “X” in “n” dependent Bernoulli trials; the distribution is best understood in terms of the

Binomial identity NCn = mC0 N-m Cn + ...+ mCx N-m Cn-x +... + mCm N-m Cn-m which when divided by NCn

yields the distribution mCx N-m Cn-x where X takes on values x=[xmin, xmax] where xmin=N-n-m and xmax=

min(n,m).as allowed by the combinations w/o replacement

The Poisson RV “X” answers the question “how many successes X in n Bernoulli trials with n very

large?” We shall discuss this in more detail in the second part of the course where we pair it with a

continuous distribution. For now it is sufficient to know that it represents a limiting behavior of the

Binomial PMF in the limit that n-> inf and its terms represent single terms in the expansion of ea where a

=λ∗ t is called the Poisson parameter, where λ is a “rate” and t is a time interval for the data run. The PMF

is therefore the ratio of the single term in the expansion to ea over ea which is

pX(x)={ ax/ x!} / ea for x=0,1,2,3,... The Poisson RV has many applications in physics and engineering.

The Riemman Zeta RV “X” has applications to Language processing and prime number theory and its

properties are given in the table. Note that the exponent must satisfy α >0 in order to avoid the harmonic

series which will does not converge and therefore cannot satisfy the sum to unity condition on the PMF.

141](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-27-320.jpg)

![Chapter 5 – Continuous RVs

Probability Density Function (PDF)

f X (x)

Event E = {x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

:

b

Pr[ x ∈ E ] = ∫ f X ( x)dx = ∫ f X ( x)dx Pr[a ≤ x ≤ b]

E a a x

2.0 b

Pr[ x = 2.0] = ∫f

x = 2.0

X ( x)dx = 0 Prob at a point = 0 Except for δ-fcn at a point

αδ ( x − x0 ) uniform

Mixed Continuous & Discrete Outcomes – Dirac δ-fcn f X (x) β

(b − a )

β

f X ( x) = αδ ( x − x0 ) +

(b − a )

b x0 + ε

x

∫ αδ ( x − x )dx = ∫ ε αδ ( x − x )dx =α

a

0

x0 −

0

a x0 b

Sampled Continuous Fcn g(x) f X (x) α k δ ( x − xk )

n

g (x)

f X ( x ) = ∑ α k δ ( x − xk )

k =0

b

α k = ∫ g ( x)δ ( x − xk ) =g ( xk )

a x0 x1 xk xn x

2/24/2012 3

In Discrete Probability a RV is characterized by its probability mass function (PMF) pX(x) which

specifies the amount of probability associated with each point in the discrete sample space. Continuous

probability generalizes this concept to a probability density function (PDF) fX(x) defined over a

continuous sample space. Just as the sum of pX(x) over the whole sample space must be unity, the

integral of fX(x) over the whole sample space must also be unity. An event E is defined by a sum or

integral over a portion of the sample space as shown by the shaded area in the upper figure between x=a

and x=b.

The middle panel gives an example of a mixed distribution containing continuous uniform distribution

β/(b-a) and a Dirac δ-function at the point x0 α∗ δ(x-x0) corresponding to a discrete contribution at that

point. The uniform distribution is shown as a continuous horizontal line at “height” y = β between a and

b and the Dirac δ-function is shown with an arrow corresponding to a probability mass “α” accumulated

at a single point x=x0.. The integral over the continuous part gives (b-a)* β/(b-a) = β and the integral of

the Dirac δ-function α∗ δ(x-x0) over any interval containing x0 yields α. Thus, in order for this

expression to be a valid probability density function, we require the sum of the two contributions be

unity: α+ β =1 .

Consider the continuous curve fX(x) = g(x) in the bottom panel and take the sum of products αk*δ(x-xk).

Is this a valid discrete “PMF”? In order for this to be so the sum of the contributions αk must be unity.

Does it represent a digital sampling of g(x)? No, in order to actually write down an appropriate

“sampled” version of g(x), we need to develop a “sampling” transformation Yk=Yk(X) for k=0,1,2,...,n so

as to transform the original continuous fX(x) to a discrete fY(yk) (See slide#26 )

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-28-320.jpg)

![Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF)

x

FX ( x) = Pr[ X ≤ x] = ∫ f X ( x ') dx ' Probability Density PDF

x '=−∞

integrates to yield CDF

fX(x) fX(x) PDF

Bdy Values : FX (−∞) = 0 ; FX (+∞) = 1 PDF

1 1

¼ δ(x-1)

1/2

Monotone Non - decr. : FX (b) ≥ FX (a ) ; if b ≥ a 0 x x

0

0 1/2 1 3/2 0 1/2 1 3/2

Prob Interpretation : Pr[a ≤ x ≤ b] = FX (b) − FX (a)

FX(x) CDF FX(x) CDF

Density PDF : d

dx FX ( x) = f X ( x)

1 1

¼

1/2 1/2

or, dFX ( x) = FX ( x + dx) − FX ( x) = f X ( x)dx

0 x 0 x

0 1/2 1 3/2 0 1/2 1 3/2

2/24/2012 7

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) for a continuous probability density function fX(x) is defined

in a manner similar to that for discrete distributions pX(x) except that the cumulative sum over a discrete

set is replaced by an integral over all X less than or equal to a value x. This integral yields a function of

“x” FX(x) = Pr[X<=x] which has the following important properties

(i)FX(x) always starts at 0 and ends at 1

(ii)FX(x) is continuous,

(iii)FX(x) is non-decreasing,

(iv)FX(x) is invertible; i.e., FX -1 (x) exists, and

(v)The density fX(x)=d/dx{FX(x)} (since exact differential d FX(x) = FX(x+dx) - FX(x) = fX(x)dx )

It is important to note all five properties of FX(x) as they have important consequences.

The figure shows the relationship between the density fX(x) and the cumulative distribution FX(x) for two

cases (i) two regions of constant density (two “boxes”) and (ii) one region of constant density plus a delta

function (one “box” and an arrow “spike”) .

In case (i) FX(x) ramps from a value of 0 to ½ in the region [0, ½ ] from the 1st constant density box, then

remains constant at ½ over the region [ ½ , 1] and finally ramps from ½ to 1 from the 2nd constant

density box. Note that the slopes of the two ramps are both “1” in this case and that the total area under

the density curves 1* [1/2-0] + 1* [3/2-1] = 1.

In case (ii) FX(x) ramps from a value of 0 to ½ in the region [0, 1] by virtue of the constant “½” density

box, then jumps by “1/4” because of the delta function, and finally continues its ramp from the value ¾ to

1. Note that this is simply the superposition of a constant density of “ ½“ plus a delta function ¼∗ δ(x-

1), and again the total area under the density curves ½ * [3/2-0] + ¼ = 1

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-29-320.jpg)

![Transformations of Continuous RVs

• Transformation of Densities PDFs in 1 dimension

• Transformation of Joint Densities PDFs in 2 or more dimensions

• Two Methods:

1) CDF Method:

Step#1) First find CDF FX(x) by integrating fX(x)

Step#2) Invert y=g(x) transformation y = g(x) ⇒ x = g −1 ( y )

& use it to write FY ( y ) = Pr[Y ≤ y ] in terms of the known FX(x)

(Note y= g(x) may not be “one-to-one” “multiplicity”)

y '= y

Step#3) Differentiate wrt y: d d

fY ( y ) =

dy

FY ( y ) =

dy ∫f

y '= −∞

Y ( y ' )dy '

2) Jacobian Method: Transform PDF fY(y) using derivatives f X ( x)

fY ( y ) =

Express everything in terms of variable y dy dx

fY ( y )dy = f X ( x)dx ; y = g ( x) f X ( x = g −1 ( y ))

=

g ' ( x = g −1 ( y ))

Note absolute value

2/24/2012 14

It is very important to understand how probability densities change under a transformation of coordinates

y=g(x). We have seen several examples of such coordinate transformations for discrete variables,

namely,

(i) Dice: Transform from individual dice coordinates (d1, d2) to the sum and difference coordinates (s, d)

corresponding to a 90 degree rotation of coordinates, and

(ii) Dice: Transform from individual dice coordinates (d1, d2) to the minimum and maximum coordinates

(z, w) corresponding to corner shaped surfaces of constant minimum or maximum values.

There are two methods for transforming the densities of RVs, namely (i) the CDF-method and (ii) the

Jacobian Method. While they are both quite useful for 1-dimensional PDFs fX(x), the Jacobian method is

best for transforming joint RVs .

The CDF method involves three distinct steps as indicated on the slide, namely (i) compute CDF FX(x),

(ii) Relate FY(y) = Pr[Y<=y] to FX(x) and then invert the transformation x = g-1(y) and substitute to find

FY(y) with a redefined y domain, and (iii) differentiate wrt “y” to obtain the transformed probability

density for the RV Y: fY(y). Note that if the function is multi-valued and therefore not invertible, it must

be broken up into intervals for which it is invertible and appropriate “fold-over” multiplicities must be

accounted for.

The Jacobian Method uses derivatives of the transformation to transfer densities from the original set of

RVs to the new one; the Jacobian accounts for linear, areal, and volume changes between the coordinates.

In one dimension the Jacobian is simply a derivative and is obtained by transferring the probability in the

interval x to x+dx: fX(x)dx to the probability in the interval y to y+dy: fY(y)dy Equating the two

expressions yields fY(y) =fX(x) / |dy/dx| = fX(g-1(y) ) / |dy/dx|. Note that the absolute value is necessary

since fY(y) must always be greater than or equal to zero.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-30-320.jpg)

![Method#1

Transformation of Continuous RV - CDF Method

Resistance X = R Step#1 Compute FX(x) CDF= FX(x)

PDF = fX(x)

1/ 200 900 ≤ r ≤ 1100

f R (r ) = 1

0 Otherwise

1/200

r '=r 0 r < 900

FR (r ) = Pr[ R ≤ r ] = ∫ f R (r ')dr ' = (r − 900) / 200 900 ≤ r ≤ 1100

0

r '=−∞ 1 r > 1100 900 1100 x

Conductance Y = 1/R Step#2 Transform to FY(y)

PDF = fY(y)

FY ( y) = Pr[Y ≤ y] = Pr[ R ≥ 1/ y] = 1 − Pr[ R ≤ 1/ y]

6050

1− 0 = 1 1/ y < 900 CDF= FY(y)

1

( − 900)

y 1

= 1 − FR (1/ y) = 1 − 900 ≤ 1/ y ≤ 1100

200

1 −1 = 0 1/ y > 1100 4050

Step#3 Differentiate FY(y) 0 y<

1

1100

1 0

d 1 1

fY ( y ) = FY ( y ) = ≤ y≤ 1/1100 1/900 y

dy 200 y 2 1100 900

0 1

y>

900

2/24/2012 15

The Resistance X=R of a circuit has a uniform probability density function fR(r)=1/200 between 900 and

1100 ohms as shown in the top panel; the corresponding CDF FR(r) is the ramp function starting at “0”

for R<=900 and reaching “1” at R=1100 and beyond as shown. The detailed analytic function is given in

the slide and represents the result of Step#1 in the CDF-Method.

The problem is to find the PDF for the conductance Y=1/X = 1/R. We first down the definition for FY(y)

for a given value Y=y and then re-express it as a function of R =1/Y

FY(y) =Pr[Y<=y] = Pr[R>=(1/y)] = 1-Pr[R<=(1/y)]

= 1 – FR(1/y )

This last expression is now evaluated in the lower panel of the slide by substituting r=1/y into the

expression for FR(1/y ) of the upper panel. Note the resulting expression has been written down by direct

substitution and the intervals have been left in terms of 1/y. (This constitutes step#2 of the method).

Finally, differentiating FY(y) wrt “y” we find (step#3) the desired PDF fY(y); we have also “flipped” the

“1/y” interval specifications and reordered the resulting “y” intervals in the customary increasing order.

As seen in this example, the CDF method requires careful attention to the definition of the FY(y) defined

in terms of cumulative probability of the variable Y. Since Y=1/R, this leads to FY(y) = 1-

FR(1/y ) and a reverse ordering of the inequalities for the intervals.

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-31-320.jpg)

![Transformation of Continuous RV - Derivative (Jacobian) Method

Method#2

PDF

1 / 200 900 ≤ r ≤ 1100 6050

f R (r ) =

0 Otherwise 1

fY ( y ) =

fY ( y )dy = f R (r )dr ⇒ Find fY ( y ) 200 y 2

dr f (r ) 4050

fY ( y ) = f R (r ) = R

dy | dy / dr | 1 1

f X ( x) =

200 dy y=

fY ( y ) =

f R (r )

=

(1 / 200)

900 dx R

| −1 / r |2

y2 hyperbola: xy = 1

dy

slope =

dx

1 1 1

fY ( y ) = for ≤ y≤

200 y 2 1100 900 1100

x=R

Note: fY(y) is large for small slope & vice versa.

Same Differential Area (Probability) is mapped via hyperpola

to yield the tall high and short fat strip areas shown for fY(y)

2/24/2012 16

The Jacobian Method is much more straight forward and moreover has a very intuitive visualization in

the 3-dimensional plot shown on this slide. The uniform probability density function fR(r)=1/200 between

900 and 1100 ohms is written explicitly in the first boxed equation. The Jacobian method just takes the

constant fR(r) = 1/200 and divides it by the magnitude of the derivative |dy/dr|=|-1/r2| = y2 to yield directly

fY(y)=1/(200y2) for y ε [1/1100, 1/900].

The 3-dimensional plot shows exactly what is going on:

i) The original uniform distribution fX(x)=1/200 displayed as a vertical rectangle in the x-z plane ii)

Sample strips at either end with width “dx” have the same small probability dP= fX(x)dx as shown At

R=900, the density fX(x) is divided by the large slope |dy/dx| yielding a smaller magnitude for fY(y) as

illustrated, but this is compensated by a proportionately larger “dy”and thus transfers the same small

probability dP= fY(y)dy.

iii) Conversely, the strip at R=1100 is divided by a small slope |dy/dx| and yields a larger magnitude for

fY(y), which is compensated by a proportionately smaller “dy” again transferring the same dP.

iv) The end point values of the transformed density fY(y) are illustrated in the figure. The strip width “dx”

cuts the x-y transformation curve at two red points which have a “dy” width that is small at x =1100 and

large at x = 900 as determined by the slope of the curve. The shape in between these end points is a

result of the smoothly varying slope of the transformation hyperbola shown in the x-y plane.

Thus the slope of the transformation curve (hyperbola xy=constant in this case) in the x-y plane

determines how each “dx” strip of the uniform distribution fX(x)=1/200 in the x-z plane transfers to the

new density fY(y) shown in the z-y plane. This 3-dimensional representation de-mystifies the nature of

the transformation of probability densities and makes it quite natural and intuitive for 1-dimensional

density functions. It is easily extended to two-dimensional joint distributions.

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-32-320.jpg)

![Analog to Digital (A/D) Converter - Series of Step Functions

Continuous Representation of Discrete “sampled” Distributions Y (OUT)

3

A/D converter

Mapping Fcn Y = g( X ) = k +1 ; k < x ≤ k +1 -3

2

1

-2 -1

X

Mapped Density fY (y) = ∑ αk ⋅ δ(y − yk ) 0

-1 1 2 3 (IN)

k -2

a) Exponential b) Gaussian b) Uniform

1 −x2 / 2

ae − ax PDFX = f X ( x) = e 1 0 ≤ x ≤ 10

x≥0 2π PDFX = f X ( x) =

PDFX = f X ( x) = 0 otherwise

0 x<0 −∞ < x < ∞

k k

α k = ∫ f X ( x)dx = x =∫ −1

k

ae − ax dx = −e − ax x≥0 k

1 − x2 / 2 k

k − (k − 1)

k

x = k −1 αk = ∫ 2π

e dx = ϕ (k ) −ϕ (k − 1) αk = ∫

1

dx =

x = k −1 0 x<0

x = k −1 10 10

x=k

1 − x2 / 2

x = k −1

1

e − ak (ea − 1) x ≥ 0

ϕ (k ) ≡ ∫ 2π

e dx ; k ∈ (−∞, ∞ ) =

10

; k = 1, 2,L ,10

= ; k = 1, 2,... x =−∞

0 x<0

∞ 10

1

fY ( y ) = ∑ e − ak (e a − 1) ⋅ δ ( y − k ) fY ( y ) = ∑ α k ⋅ δ ( y − yk ) fY ( y ) = ∑ δ ( y − k)

k =1 k k =1 10

e − (0.1) k (e0.1 − 1) = .105 ⋅ e − (0.1) k fY(y)

fY(y)

k αk

fY(y)

0.1 α kδ ( y − k )

1 0.095 1/10

0.095 2 0.086

0.050 3 0.078 y y

0 1 5 10

y

0 10 20 11 0.035

2/24/2012 26

In discussing the half-wave rectifier on the last slide we found that the effect of a “zero” slope

transformation function was to pile up all the probability in the x-interval into a single δ-function at the

constant y=“0” value associated with that part of the transformation. Here we extend that concept to a

“sample & hold” type mapping function typical of an Analog to Digital (A/D) converter. The specific

mapping function y=g(x) = k+1 for k < x ≤ k+1 is illustrated in the grey box as a series of horizontal

steps over the entire range of x [-3, 3]; the y-values for these steps range from y=-2 to y=+3. Each

horizontal (zero-slope) line accumulates the integral of fX(x) from x=k to k+1 onto its associated y-value

shown as a red circle with the point of a δ-function arrow pointing up out of the page and having an

amplitude given by the integral for that interval denoted by the symbol αk.

The table shows several examples of a digitally sampled representation for a) Exponential, b) Gaussian,

and c) Uniform distributions in the three columns. The rows of the table give the specific continuous

densities for each, the computations for the amplitudes of the discrete digital samples αk, the resulting

sum of δ-functions, and finally a plot showing arrows of different lengths to represent the δ-functions of

the sampled distributions.

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-34-320.jpg)

![Order Statistics - General Case n Random Variables

General Case n Variables: X1,, X2 , ... ,, Xn RVs fX (x) fX(y)dy

Assume RVs are Indep and Identically Distributed (IID) FX ( y ) 1 − FX ( y )

{X1,, X2 , ... ,, Xn } fX(x)

f X 1 X 2 L X n ( x1 x 2 L x n ) = f X ( x1 ) ⋅ f X ( x 2 ) ⋅ L ⋅ f X ( x n )

Reorder {X1,, X2 , ... ,, Xn } as follows: fX(y)dy

Y1,= smallest {X1,, X2 , ... ,, Xn } all Yk <y y y+dy all Yk > y

Y2= next smallest {X1,, X2 , ... ,, Xn } Y1 |Y2 |… |Yj-1 Yj+1 | Yj+2 | … | YN

jth “order

Yj= jth smallest {X1,, X2 , ... ,, Xn } (j-1) RVs

statistic” (n-j) RVs

Yn= largest {X1,, X2 , ... ,, Xn }

Each IID: P[Yj ≤ y]= FX(y) P[Yj > y]= 1 - FX(y)

Y1< Y2 < Yj <… < Yn

[FX(y)]j-1 [1 - FX(y)]n-j

Same PDF in variable “y” fX(y)

Diff’l Prob.

Find PDF for the jth “order statistic” “one sequence” = ( FX ( y ) ) j −1 ⋅ f X ( y )dy ⋅ (1 − FX ( y ) )n − j

Pr[ y ≤ Y j ≤ y + dy ] = fY j ( y )dy ; j = 1, 2,L , n jth order statistic

3! [φ| X1 | X2 X3]

j=1: [φ| Y1 |Y2 Y3 ] 0! 1! 2!

=3 [φ| X2 | X1 X3]

Case n=3 {Min, Mdl, Max};Y2 = “Mdl“statistic. Min [φ| X3 | X1 X2]

Y2 could be any one of {X1,, X2 , X3 } 3!

[X2,| X1 | X3], [X3,| X1 | X2]

j=2: [Y1 |Y2 | Y3 ] =6 [X1,| X2 | X3], [X3,| X2 | X1]

1! 1! 1! [X1,| X3 | X2], [X2,| X3 | X1]

Mdl

There are 3! = 6 orderings; however, we partition into 3 [ X2 X3 |X1 |φ]

3!

groups and permutations within a group is irrelevant; j=3: [Y1 Y2 | Y3 | φ] 2! 1! 0!

=3 [ X1 X3 |X2 |φ]

[ X1 X2 |X3 |φ]

Max 48

2/24/2012

Order Statistics for the general case of n IID Random Variables is detailed on this slide. The n IID RVs

{X1, X2,..., Xn} are re-ordered from the smallest Y1 to the largest Yn and the jth Y in the sequence Yj is

called the “jth order statistic”. Again we fix a value Y=y and consider the continuous range of re-ordered

Y-values illustrated in the figure: the small interval from y to y+dy contains the differential probability

for the jth order statistic Yj given by fX(y)dy; all Y-values less than this belong to the Y1 through Yj-1 and

those greater belong to Yj+1 through Yn as shown in the inset figure. Now for each of the Ys on the left we

have the probability Pr[Y1 ≤ y] = FX(y), Pr[Y2 ≤ y] = FX(y), ... Pr[Yj-1 ≤ y] = FX(y), and because they are

IID the total probability of those on the left is Pr[Yleft ≤ y] = [FX(y) ]j-1; similarly on the right we find

Pr[Yright ≤ y] = [1-FX(y) ]n-j. So for the reordered Ys the differential probability is just the product of these

three terms multiplied by a multiplicity factor α, viz.,

dP = Pr[y≤ Yj ≤ y+dy]= f Yj (y) dy = α [FX(y) ]j-1 fX(y) [1-FX(y) ]n-j dy

The multiplicity factor α results from the number of re-orderings of {X1, X2,..., Xn} for each order

statistic Yj ; arguments for n=3 and n=4 are illustrated on this slide and the next. These arguments look

(in turn) at each order statistic min, middle(s), and max and compute in each case the number of distinct

arrangements of {X1, X2,..., Xn} that yield the three groups relative to the “separation point” Y=y and

arrive at multinomial forms dependent upon the orderings for each statistic. The specific multiplicity

factors for the cases for n=3,4 are easily found to be

α = 3C (j-1),1,(3-j) = 3! / [(j-1)! 1! (3-j)!] ; α = 4C (j-1),1,(4-j) = 4! / [(j-1)! 1! (4-j)!]

and the final results for the PDF of the jth order statistic f Yj (y) in these cases are

fYj (yj) = 3C (j-1),1,(3-j) [FX(yj) ]j-1 fX(yj) [1-FX(yj) ]3-j for j=1,2,3 (n=3)

fYj (yj) = 4C (j-1),1,(4-j) [FX(yj) ]j-1 fX(yj) [1-FX(yj) ]4-j for j=1,2,3,4 (n=4)

48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-35-320.jpg)

![Multi-User Digital Communication “CDMA” Arrival Slots

• Two signals s1 , s2 ;Decode s1 or s2 in given time slot s1 Decoded

P|s1,1]= P[1|s1] P|s1] “success”

• a priori Prob: P[s1]=3/4 ; P[s2]=1/4 P[1|s1] =(2/3)(3/4) =1/2 p1=1/2

S1 2/3

• Decoding Statistics: 1/3

P[s1] 3/4 P[0|s ]

P|s1,0]=1/4

decoded “1” : P[1|s1]=2/3 ; P[1|s2]=2/3 Time

1

s1 Not

Slot #4 P[1|s2] P|s2,1]= P[1|s2] P|s2] Decoded

not decoded “0” : P[0|s1]=1/3 ; P[0|s2]=1/3 1/4 S2 =(2/3)(1/4) =1/6 “failure”

P[s2]

2/3

q1=1/2

1/3

Nr time slots (“trials”) n − 1 r n − r P[0|s2]

P|s2,0]=1/12

p N r ( n) = p q

r-Decodes of s1 p1=q1=1/2 r −1 a priori decode

4 −1 1

1 1 1

1) Pr[ 1st decode in 4th slot] Pr[ N1 = k ] = p N1 (k ) = q k −1

p1 ⇒ Pr[ N1 = 4] = p N1 (4) = =

2 2 16

2) Pr[ 4th decode in 10th slot | 3 decodes No memory - slots 6 to 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

“1” “1” “1”

in 1st 6 time slots ] 1 1

3

1

1 1 2 3 4

Pr[ N1 = 4] = p N1 (4) = q 3 p = = 3 “1”s

No Memory

2 2 16

4

3) Pr[ 2nd decode in 4th slot] n − 1 r n − r 4 − 1 2 4 − 2 1 3

Pr[ N r = n] = p N r (n) =

p q ⇒ Pr[ N 2 = 4] = p N 2 (4) =

2 − 1 p q = 3 2 = 16

r − 1

4) Pr[ 2nd decode in 4th slot | no decodes No memory of failures in slots 3 & 4 1 2 3 4

“0”“0”

2

in 1st 2 time slots] 1 1 1 2

Pr[ N 2 = 2] = p N 2 (2) = p 2 = =

2 4 “Renewal”

{ “means” N2>2 }

Pr[ N 2 = 4 , N 2 > 2 ] p N 2 (4) ( 3 / 16 ) 1

Pr[ N 2 = 4 | N 2 > 2 ] = = = =

Pr[ N 2 > 2 ] 1 − p N 2 ( 2 ) 1 − (1 / 4 ) 4

2/24/2012 78

This example illustrates renewal properties and time slot arrivals of the Geometric and Negative Binomial RV distributions.

In a multiuser environment the digital signals from multiple transmitters can occupy the same signal processing time slot so

long as they can be distinguished by their modulation characteristics. Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) uses a

pseudorandom code that is unique to each user to “decode” the proper signal source.

Consider two signals s1 and s2 being processed in the same time slot with a priori “system usage” given by P[s1] = ¾ and P[s2]

= ¼ ; further let “1” denote successful and “0” denote unsuccessful decodes respectively. Given that each signal has the same

2/3 probability of a successful decode P[1|s1] = P[1|s2] = 2/3, we can use the tree to find the single trial probability of success

for decoding each signal.

For signal s1 we see that the end state {s1, 1} represents a successful decode and has p1=1/2 ; all other states {s1, 0}, {s2 1},

{s2, 0} represent failure to decode signal s1 with probability q1 = 1/4+1/6 + 1/12 = 1/2. Similarly for signal s2 we see that the

end state {s2, 1} represents a successful decode of s2 and has p2 =1/6 ; all other states {s2, 0}, {s1 1}, {s1, 0} represent failure to

decode signal s2 with probability q2 = 1/12+1/2 + 1/4 = 10/12 =5/6.

We consider successive decodes of s1 as independent trials with probability of success p1=1/2 . Thus, the probability of

having r- successful decodings of s1 in Nr signal processing slots “trials” is given by the Negative Binomial PMF

pNr(n) = n-1Cr-1p1rq1n-r with nr = r, r+1, r+2, .... with p1=q1=1/2

1) Pr of 1st decode (r=1) in 4th slot (N1 =4) is pN1(4) = 4-1C1-1p11q14-1 = 1(1/2)4 = 1/16

2) Pr of 4th decode (r=4) in 10th slot (N4 =10) given 3 previous decodes in 1st 6 slots is found by “restarting the process with

slots #7 , 8, 9, 10 so we need only one decode (r =1) in 4 slots, i.e., N1 =4, which is identical to part 1) and yields

Pr[N4 = 10 | N3=6] = pN1(4) = 4-1C1-1p11q14-1 = 1(1/2)4 = 1/16

3) Pr of 2nd decode (r=2) in 4th slot (N2 =4) is pN2(4) = 4-1C2-1p12q14-2 = 3(1/2)4 = 3/16

4) Pr of 2nd decode (r=2) in 4th slot given 1st two slots were not decoded is found by “restarting the process with slots #3,4 “so

we need r=2 in the two remaining slots N2 =2 which means two successes in two trials, so we have

pN2(2) = 2-1C2-1p12q12-2 = 1(1/2)2= 1/4

78](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-37-320.jpg)

![Common PDFs - “Continuous” and Properties

RV Name PDF Generating Mean Variance

∞

Fcn

ϕ ( s) = E[e Xs ] ∫ x⋅ f

x = −∞

X ( x)dx var( X ) = E[ X 2 ] − E[ X ]2

f X (x)

1

f X ( x) = b − a

a≤ x≤b e sb − e sa a+b (b − a )2

Uniform 0

Otherwise s (b − a ) 2 12

x

a b

fT (t )

λ e − λ t t≥0 1 1

f T (t ) = λ

Exponential 0 t<0 λ λ2

λ−s “exponential wait”

λ>0 t

f Tr (t) Peaks at

Gamma λ e − λt (λt ) r −1

t≥0 Exponent r r

fTr (t ) = ( r − 1)! ial tmax = r −1

λ

λ

r

r-Erlang

0 t<0

1

r =1 E[T1] = λ λ−s λ

r = integer r =2 E[T2 ] =

2

For r=3: three

λ2

λ>0 Arrival Rate λ

3

r =3 E[T3 ] =

λ

“exponential waits”

t E[T3 ] = 1

λ

+

1

λ

+

1

λ

2

( x −µ )

Normal 1 − Gaussian

f X ( x) = e 2σ2 Rayleigh (σ s )2

2π ⋅ σ Peaks µs+ µ σ2

N (µ, σ ) e

2

2

at x=0 Peaks at

−∞ < x < ∞ x=1/a

( s/ a )2

Rayleigh a2 x2

− 1+ a e

s −

2 π

⋅ 2−π

f X ( x) = a 2 xe 2

2 1 π

2a 2

x ⋅ 1 + erf a 2

(s/a)

x>0; a>0 0

2

2/24/2012 101

This table compares some common continuous probability distributions and explores their fundamental

properties and how they relate to one another. A brief description is given under the “RV Name” column

followed by the PMF formula and figure in col#2, the generating function in col#3, and formulas for the

mean and variance in the last two columns.

The Uniform Distribution has a constant magnitude 1/(b-a) over the interval [a,b]; the mean is at the

center of the distribution (a+b)/2 and the variance is (b-a)2/12 .

The Exponential Distribution decays exponentially with time from an initial probability density λ at

t=0. The mean time for an arrival is E[T] = 1/ λ which equals the e-folding time of the exponential. Its

variance is 1/ λ2 . This cumulative exponential distribution is the probability that the first arrival T1

occurs outside a fixed time interval [0,t]; it equals the probability that the discrete number of Poisson

arrivals K(t)=0 occurs within the interval [0,t] , that is, Pr(T1>t)= Pr(K(t)=0).

The r-Erlang / Gamma Distributions for r>1, all rise from zero to reach a maximum at (r-1)/ λ and then

decay almost exponentially ~tr-1e-λt to zero. The maximum occurs after a wait of one exponential mean

wait time 1/ λ for r=1, two 1/ λ waits for r=2, and r 1/ λ waits for any r. The variance is r times that of

the exponential variance 1/ λ2 . The cumulative r-Erlang distribution is the probability that the rth arrival

time Tr occurs outside a fixed time interval [0,t] ; this equals the probability that the discrete number of

Poisson arrivals K(t) ≤ (r-1) i.e., Pr(T1>t)= Pr(K(t) ≤ (r-1)). The Gamma density is a generalization of the

rth Erlang density obtained by replacing (r-1)! with Γ(r) making it valid for non-integer values of r.

The Gaussian (Normal) Distribution is the most universal distribution in the sense of that the Central

limit theorem requires that sums of many IID RVs approach the Gaussian distribution.

The Rayleigh Distribution results from the product of two independent Gaussians when expressed in

polar coordinates and integrated over the angular coordinate. The probability density is zero at x=0 and

peaks at r=1/a½ before it drops towards zero with a “Gaussian-like” shape for x>0. It is compared with

the Gaussian which is symmetric for about x=0.

101](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-39-320.jpg)

![Consequences of Central Limit Theorem

Discrete Uniform PMF pX(x)

/

1 11

1

p X ( x) = δ ( x − xi ) ; xi = −.5,L , 0,L ,.5

11 x

-.5 -.4 -.3 -.2 -.1 0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5

Generate uniform Sequence of N=1000 points { Xi }

{Xi } .2 | .5 | -.1 | .3 | -.2 | -.1 | -.1 | .4 | -.3 | .1 | -.5 | -.1 L -.1 | .4 | -.3 | .1 | -.5 | -.1

n=2 .7 .2 -.3 .5 -.2 -.6 Sum of n Uniform Variates Xi

n

n=4 .9 .2 -.8 Z n = ∑ X i ; n = 2, 4,8,12

i =1

n=8 1.1

Plot Frequency of Occurrence f Zn ( z )

n = 12 .2

fZn ( z ) ≈ pZn ( z )

pX (x) = 1

11

Note: Curves give “shape” of 1.0

n = 2

freq of occur. for discrete points

spaced 0.1 apart

n = 4

.05

Central Limit Thm:

n = 12

=>Generates a Gaussian

as n=2,4,8,12, … large

z

2/24/2012 -2.0 - 1.0 0 1.0 2.0 109

The Discrete Uniform PMF with values at 11 discrete points ranging from x ={-.5, -.4, -.3, -.2,-.1, 0, .1,

.2,.3,.4.,.5} can be expressed as a sum of 11 δ-functions with magnitude 1/11 at each of these points as

shown in the figure. This can also be thought of as the result of a “sample and hold” transform (see

Slide#26) of a Continuous Uniform PMF fY(y) = 1/11 ranging along the y-axis from y=-.6 to y=+.5 ; for

example, the term 1/11*δ(x-(-.5)) is the δ-function located at x= -.5 generated by integrating the

continuous PMF from y= -.6 to y=-.5 which gives an accumulated probability of ”.1/(.5 –(-.6)) =1/11 at

the correct x-location.

Suppose that a sequence of 1000 numbers from the discrete set {-.5, -.4, -.3, -.2,-.1, 0, .1, .2,.3,.4.,.5} are

randomly generated on a computer to create the data run notionally illustrated in the 2nd panel . Now we

can create sum variables Zn consisting of the sum of n =2 or n= 4 or n= 8, or n=12 of these samples

from the discrete uniform PMF. According to the CLT, as we increase “n”, the resulting frequency

distribution of the sum variables “Zn“s should approach a Gaussian. The notional illustration shows what

we should expect. The dashed rectangle shows the bounds of the original uniform discrete PMF and the

other curves show the march towards a Gaussian. Note that unlike a Gaussian all these distribution are

zero outside a finite interval determined by the number of variables that are summed. The triangle shape

is the sum of two RVs and obviously the min and max are [-1, 1] for Z2 ; the Z12 RV on the other hand,

covers the range from [-6, 6]; the range increases as we sum more variables, but only as n-> ∞ does the

sum variable fully capture the small Gaussian “tails” for large |x| as required by the CLT.

This result can also be thought of in terms of an n-fold convolution of the IID RVs Xk k=1,2,...,n which

also spreads out with each new convolution in the sequence. The next slide shows the results of a MatLab

simulation of this CLT approach to a Gaussian and a plot of the results confirming the notional sketch

shown on this slide. (The MatLab script is given on the notes page of the next slide.)

109](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-40-320.jpg)

![Examples Using Markov & Chebyshev Bounds

Markov Examples:

Prob “value” of RV X

exceeds “r” times its Kindergarten Class mean height = 42” Find bound on

mean is 1/r Prob of a student being taller than 63”

1 µ X = 42 r ⋅ 42 = 63 ⇒ r = 1.5 Pr[ X ≥ 1.5 ⋅ 42] ≤ 1 / 1.5 = 66.7%

P[ X ≥ rµ X ] ≤

r

or

Note that for r =1 the Markov

E[ X ] µ X

bound is “1” or 100%;

P[ X ≥ c] ≤ = Thus useful bounds

c c

require r >1 0 µX 2µ X 3µ X

Chebyshev 1.5µ X

Prob “deviation” of RV

Ross Ex. 7-2a) Factory production

X exceeds “r” times its

std dev r σX is 1/r2 a) Given mean =50, find bound on Prob production exceeds

75, i.e., Prob[X>75] P[ X ≥ 75] ≤ E[ X ] = 50 = .667

Markov

P [ X − µ X ≥ rσ X ] ≤

1

c 75

r2 Note a upper bound: at most 66.7%

or b) Given also variance = 25 , find bound on Prob production

2 between 40 and 60

σX P[ X − 50 ≥ 10] ≤

25

P[ X − µ X ≥ k ] ≤ 10 2

= .25 Chebyshev

k2

⇒ 1 − P[ X − 50 ≥ 10] ≥ 1 − .25 = .75

Note a lower bound: at least 75%

2/24/2012 121

Here are two examples of the application of the Markov and Chebyshev Bounds. The two forms for each

are stated on the LHS of the slide for reference purposes. The decision to use one or the other of these

bounds depends upon what type of information we have about the distribution. Thus if the RV X takes on

only positive values and we only know its mean, µX , then we must use the Markov bound. On the other

hand, if the RV X takes on both positive and negative values and we know the mean, µX , and variance,

σX2, then we must use the Chebyshev bound. If in the latter case the RV X takes on only positive values,

then we could use either Chebyshev or Markov bounds, but we would choose Chebyshev over Markov

because it uses more of the information and hence will always be a tighter upper bound. Neither of these

bounds is very tight because the information about the distribution is very limited; knowing the actual

distribution itself always yields the best bounds.

1) The mean height in a Kindergarten Class is µX = 42” and we are asked “what is the probability of a

student being taller than 63?” Short of knowing the actual distribution, the best we can do is use the

Markov inequality to find an upper bound Pr[X>63] < 42/63=.67 or 67%. This is also easily computed if

we realize that the tail is the region beyond 63”= 1.5(42”) so r=1.5 and the answer is 1/1.5 =2/3=.67 .

2) The factory production has a mean output µX = 50 units and we are asked

(a) “what is the probability of a 75 unit output?” This again involves a positive quantity X the number of

units and we choose the Markov bound for 1.5(50) = 75 units so again r=1.5 and the resulting probability

is 67% .

(b) If we are also given the variance of the production σX2 = 25 the additional information allows us to

use the Chebyshev bound to find the probability in the tails on either side of the mean of 50. Thus, if we

find the probability in the 2-sigma tails (r=2) to left of 50-10 and to the right of 50+10 as Pr[Tails] ≤ 1/22

= 25%. Hence the production within the bounds [40,60] is the complementary probability

Pr[40 ≤ X ≤ 60] =1-Pr[Tails] ≥ 1-.25 = .75 or at least 75%

121](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-41-320.jpg)

![Transformation of Variables & General Bivariate Normal Distribution

r Mean Covariance

X a bivariate normal m X = E[ X ] = 0 0 1 0

(indep comp) N(0,1) mX = K XX =

K XX = E[ X ⋅ X T ] = I 0 0 1

Linear Xform to Y Y = AX + b b

mY = b = 1 KYY = AAT

b2

Computation mY mY = E[Y ] = E[ A ⋅ X + b] = A ⋅ {+ b = b

E[ X ]

r

=0

Computation KYY [ ]

K YY = E (Y − mY )(Y − mY )T = E ( Y − b)(Y − b)T = E[ AX ( AX )T ] = E[ A( XX T ) AT ] = A E[ XX T ] AT = AAT

{ 123

4 4

= AX +b =I

det K YY = det A ⋅ det AT = (det A)

2

Determinant KYY ⇒ det A = det KYY

∂y

y

A is Jacobian: det i = det{ Aij } ⇒ J = det( A) = det KYY

∂x j

x

(A ) (A ) = (AA )

−1 T −1 T −1

−1

= K YY

1

( )

T

− A−1 ( y − b ) ⋅ A−1 ( y − b )

1 2

New Prob Density f X ( x) e

fY ( y ) = y1 y2

= 2π

J

x

det KYY

1 x2

1 − 2 [( y − m y )T KYY −1 ( y − m y ) ]

1

(No Longer Independent

General Bivariate e

f Y ( y ) = 2π

Normal Distribution Components or zero

det KYY means & unit variances)

2/24/2012 132

We introduced the Bivariate Gaussian distribution for the case of two independent N(0,1) Gaussians

(with the same variance =1) and arrived at a zero mean vector mX and a diagonal covariance matrix KXX

=diag(1,1) corresponding to a pair of uncorrelated Gaussian RVs and displayed in the first line of the

table. The second line of the table shows the results of making a linear transformation of variables

Y=AX+b from the X1 X2 coordinates to the new Y1 Y2 coordinates; note that the vector b =[b1,b2]T

represents the displaced origin of the Y1 Y2 coordinates relative to X =[0,0]T. We see that the new mean

vector is no longer zero but rather mY = b and the new covariance KYY =AAT no longer has unit

variances along the diagonal, but, in general, now has non-zero off-diagonal elements as well. The fact

that this linear transformation yields non-zero off-diagonal elements in the covariance matrix means that

the new RVs Y1 Y2 are no longer uncorrelated.

The computations supporting these table entries are straightforward. The new mean is obtained by taking

the expectation E[Y]= E[AX+ b] and using the fact that the original mean E[X] is zero to give mY =

E[Y]= b . Substituting this value b for mY in the covariance expression KYY = E[(Y-b)(Y-b)T] yields

KYY = E[(AX)(AX)T] = A E[XXT] AT =A AT since E[XXT] =KXX = I (i.e., the identity matrix diag(1,1)).

In order to find the new Bivariate density fY1,Y2(y1,y2) we need to divide fX1,X2(x1,x2) by the Jacobian

determinant J(Y,X) and replace X by A-1(Y-b). This Jacobian is found by differentiating the

transformation Y=AX+b to find J=det[∂Y / ∂X ] = det(A) ; note that this is easily verified by writing out

the two equations explicitly and differentiating y1 and y2 with respect to x1 and x2 to obtain the partials

∂yi / ∂xj = aij and then taking the determinant to find the Jacobian. Taking the det(KYY) =det(AAT) and

using the fact that the determinant det(A) = det(AT), we find that detA = det (KYY)½ . Finally substituting

this and X = A-1(Y-b) yields the general Bivariate Normal Distribution fY(y) given in the grey boxed

equation at the bottom of the slide. Be careful to note that the inverse KYY-1 occurs in the exponential

quadratic form and that the matrix KYY occurs in the denominator det (KYY)½ ; also observe the

“shorthand” vector notation for the bivariate density fY(y) in place of the more explicit fY1,Y2(y1,y2).

132](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-42-320.jpg)

![Ellipses of Concentration

1D Gaussian Distribution 2D Gaussian Distributions described

described by two scalars: by vector & Matrix: mean vector

mean µX & Var(X) intuitive Tabulate Area mX & Covariance KXX

Normalized & Centered RV x

1 −t / 2

Φ( y) = ∫ e dt

2

Vector mX and KXX are not very intuitive!

Standardized Distribution 2π

t = −∞ 1

Tabulation of CDF 1 − xT K XX −1 x

f X ( x1 , x2 ) = e 2

2π det K XX

fX(x) Y=

X − µX fY(y)

σX

Gaussian

σX σX Probability

Surface

x y y x2

µX 0

“Level Curves”

Prob Density Standardized Density 2 d Ellipses x1

“Level curves” of Zero x2 x

2

−1 1 2ρx1 x2

Mean 2D Gaussian Surface xT K XX x = 12− + 2 2 = c 2 = const.

with Covariance KXX (

1 − ρ2 ) σ X1

σ X1 σ X 2 σ X 2

2/24/2012 138

The 1-dimensional Gaussian distribution is completely described by two scalars the mean µX and the

variance σX2. The tabulation of a single integral for the cumulative distribution function FY(y) shown in

the left box is sufficient to characterize all Gaussians X: N(µX , σX2 ) if we first transform to a

standardized Gaussian RV Y via Y = X- µX) / σX. The Gaussian integral representing the probability

distribution for the standardized Pr[Y≤y] = FY(y) is used so often it is denoted as the “Normal Integral”

Φ(x).

We would like to extend this concept of a single tabulated integral to describe all 2-dimensional Gaussian

distributions; however, as we have seen, the Bivariate Gaussian distribution requires more than just the

means and variances of two Gaussians as we must also characterize their “co-variation” by specifying

their correlation coefficient ρ. Thus we must specify the two elements of the mean vector µX and all three

elements of the (symmetric) covariance matrix KXX in order to completely characterize a Bivariate

Gaussian fX1X2(x1,x2) given in the right box of the slide.

We have seen that the level “surfaces” (actually curves) of the Gaussian PDF are ellipses centered about

the mean vector coordinates µX1 and µX2 and described by quadratic form xTK-1XX x in the exponent of

the PDF. The explicit equation for the level curves with zero mean is obtained by setting this term equal

to an arbitrary positive constant c2 as given by the equation in the slide. These ellipses are called ellipses

of concentration because the area contained within them measures the concentration of probability for the

specific “cut through” the PDF surface. In the next few slides we will show how this leads to a single

tabulated function for the Bivariate Gaussian that is analogous to Φ(x) for the Normal Distribution.

138](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofengineeringprobabilitycoursesampler-120306115150-phpapp02/85/Fundamentals-of-Engineering-Probability-Visualization-Techniques-MatLab-Case-Studies-44-320.jpg)

![Closure Under Bayesian Updates - Summary

Summary: r X ρ

rr X 0 1

Started with a pair of N(0,1) RVs X & Y with correlation ρ X = µX ≡ E = K XY =

1

Y Y 0 ρ

1) The joint distribution is a correlated Gaussian in X and Y x 2 − 2 ρ xy + y 2

−

2(1− ρ 2 )

f XY ( x, y ) = 1

e

2

2π 1− ρ 2

e − y /2

2) Marginal fY(y) is found to be N(0,1): fY ( y ) =

2π ( x − ρ y )2

−

3) Bayes’ Update fX|Y(x|y) is Gaussian 2(1− ρ 2 )

N ( ρ y,1 − ρ 2 ) f X |Y ( x | y ) = 1

e

2π (1− ρ 2 )

4) Pick off “conditional” mean & variance from fX|Y(x|y) µ X |Y ≡ E[ X | Y ] = ρy ; Var ( X | Y ) = 1 − ρ 2