The document provides an overview of topics related to compressible fluid flow, including:

- Continuity, impulse-momentum, and energy equations for compressible fluids under isothermal and adiabatic conditions.

- Basic thermodynamic relationships like the ideal gas law, processes like isothermal and adiabatic, and concepts like internal energy and entropy.

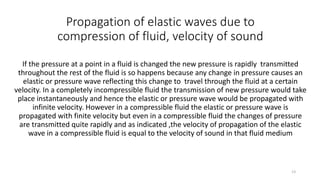

- Propagation of elastic waves in fluids due to compression, and how the velocity of sound depends on factors like pressure, temperature, and fluid properties.

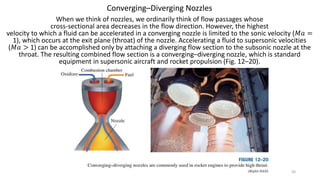

- Additional topics covered include stagnation properties, flow through converging-diverging passages, shock waves, and external aerodynamic flows.

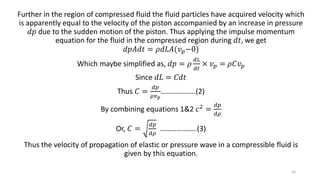

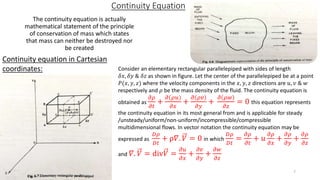

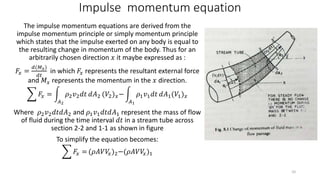

![Continuity Equation for one dimensional flow

Consider a tube shaped elementary parallelepiped along a

stream-tube of length 𝛿𝑠 as shown in figure. Since the flow

through a stream-tube is always along the tangential direction

there is no component of velocity in the normal direction. If at

the central section of the elementary stream-tube ,𝐴 is the

cross sectional area, 𝑉 is the mean velocity of flow, 𝜌 is the

mass density of the fluid then the mass of fluid passing this

section per unit time is equal to 𝜌𝐴𝑉

The mass of fluid entering the tube per unit time at section

𝑁𝑀 = [𝜌𝐴𝑉 −

𝜕

𝜕𝑠

(𝜌𝐴𝑉)

𝛿𝑠

2

]

Similarly the mass of fluid leaving the tube per unit

time at section 𝑁′ 𝑀′ = [𝜌𝐴𝑉 +

𝜕

𝜕𝑠

(𝜌𝐴𝑉)

𝛿𝑠

2

]

Therefore the net mass of fluid that has remained

per unit time= −

𝜕

𝜕𝑠

(𝜌𝐴𝑉) 𝛿𝑠 The mass of fluid in

the tube = 𝜌𝐴 𝛿𝑠 and its rate of increase with time

=

𝜕

𝜕𝑡

𝜌𝐴 𝛿𝑠 =

𝜕

𝜕𝑡

𝜌𝐴 𝛿𝑠 8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluidmechanics-170404114603/85/Fluid-mechanics-8-320.jpg)

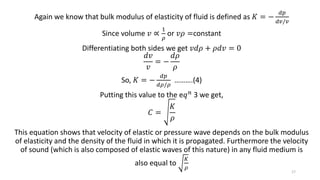

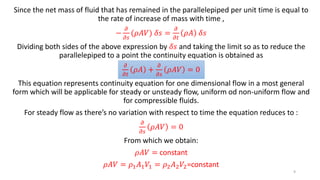

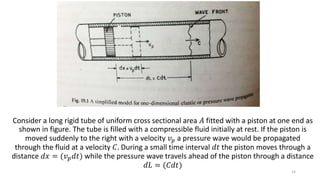

![Before the sudden motion of the piston the fluid within the length 𝑑𝐿 has an initial

density 𝜌 and its total mass is (𝜌 𝑑𝐿 𝐴) .after the piston is moved through a distance 𝑑𝑥

the fluid density within the compressed region of length (𝑑𝐿 − 𝑑𝑥) will be increased and

becomes (𝜌 + 𝑑𝜌). Thus the total mass of fluid in the compressed region will be [(𝜌 +

𝑑𝜌) 𝑑𝐿 − 𝑑𝑥 𝐴] therefore according to the principle of continuity 𝜌 (𝑑𝐿) 𝐴 = (𝜌 + 𝑑𝜌)

𝑑𝐿 − 𝑑𝑥 𝐴

Or, 𝜌 (𝑑𝐿) =(𝜌 + 𝑑𝜌) 𝑑𝐿 − 𝑑𝑥

But 𝑑𝐿 = Cdt and 𝑑𝑥 = 𝑣 𝑝 𝑑𝑡 the above equation becomes,

𝜌 (𝐶𝑑𝑡) =(𝜌 + 𝑑𝜌) 𝐶 − 𝑣 𝑝 𝑑𝑡

Or, 0 = Cd𝜌 − 𝜌𝑣 𝑝 − 𝑑𝜌𝑣 𝑝

Since the velocity 𝑣 𝑝 of the piston is much smaller than the elastic wave velocity 𝐶 the

term 𝑑𝜌𝑣 𝑝 maybe neglected and hence 𝐶 𝑑𝜌 = 𝜌𝑣 𝑝 or 𝐶 =

𝜌𝑣 𝑝

𝑑𝜌

………………….(1)

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluidmechanics-170404114603/85/Fluid-mechanics-15-320.jpg)