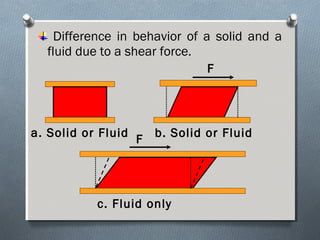

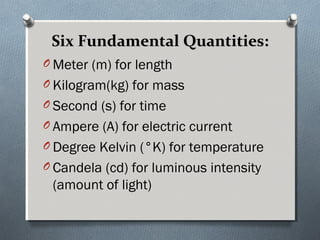

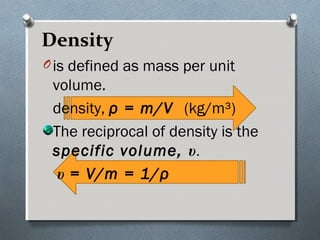

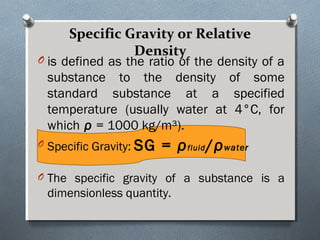

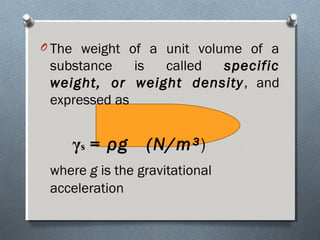

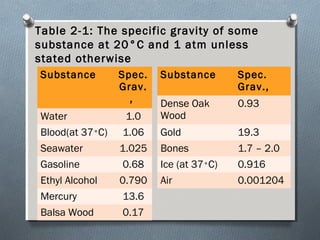

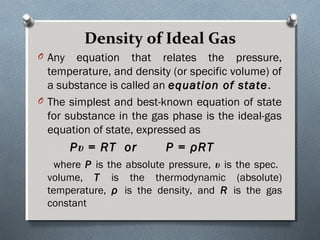

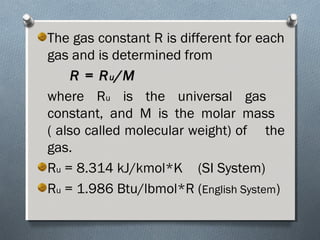

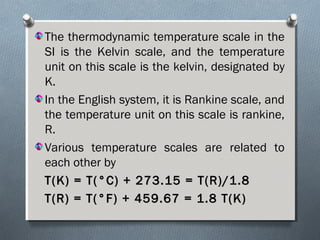

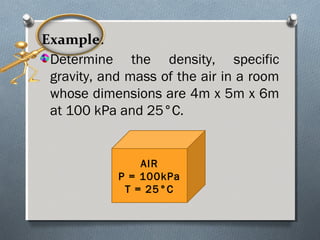

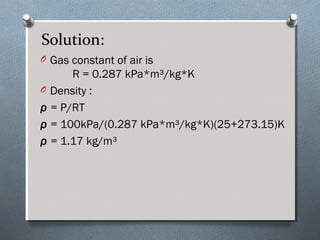

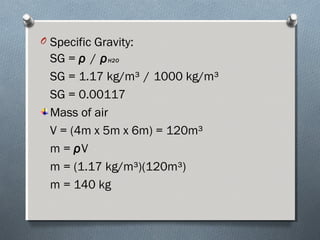

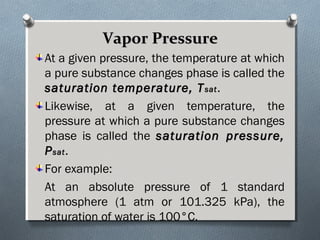

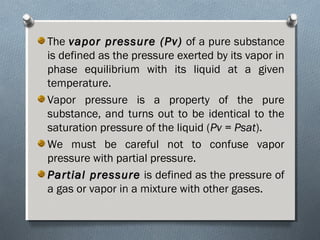

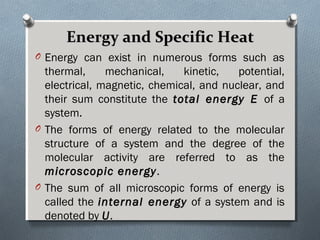

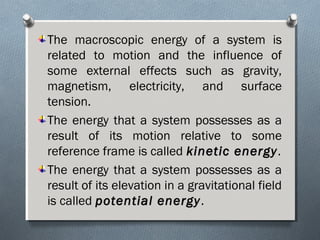

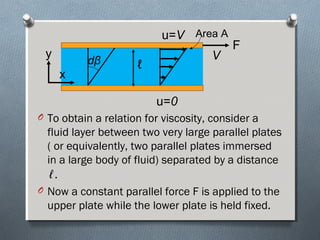

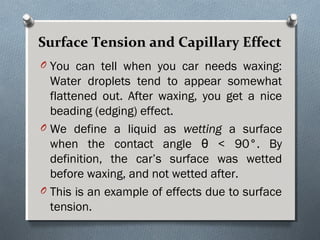

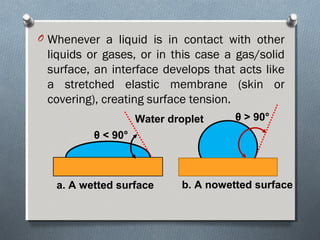

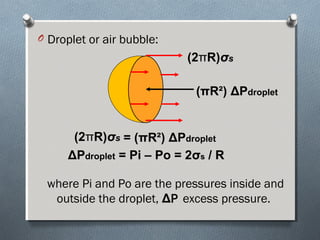

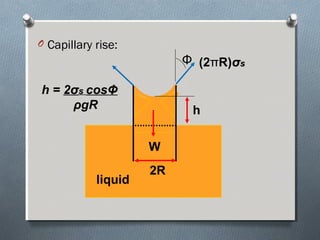

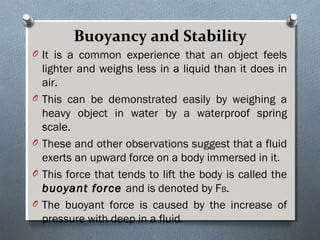

This document discusses fluid mechanics and defines key terms. It begins by defining fluid mechanics as the science dealing with fluids at rest or in motion. Fluid mechanics is then divided into several categories based on the type of fluid flow, such as hydrodynamics, hydraulics, gas dynamics, and aerodynamics. The document goes on to define properties of fluids like density, specific gravity, vapor pressure, energy, and viscosity. It also discusses concepts like the ideal gas law, temperature scales, and surface tension.