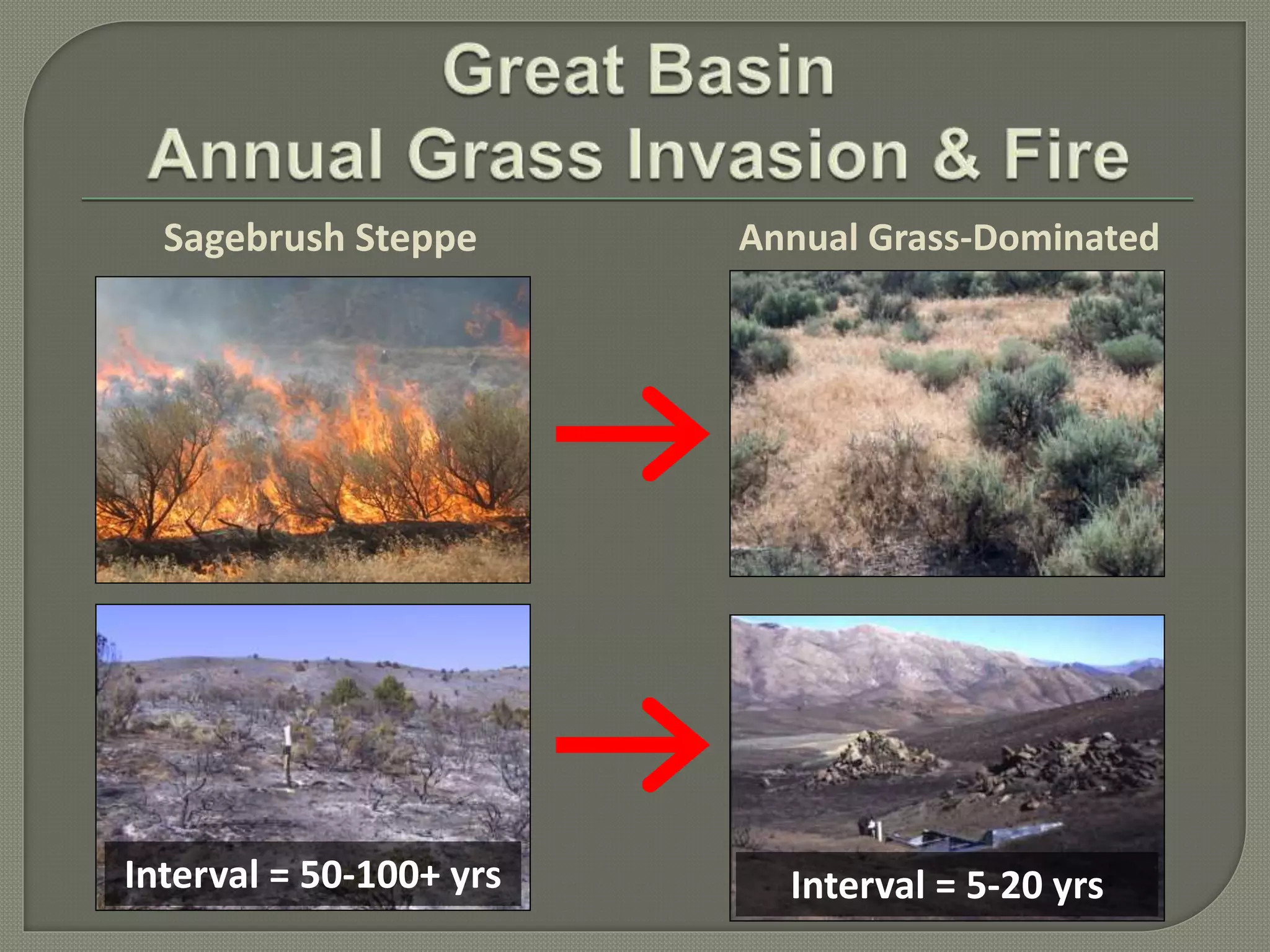

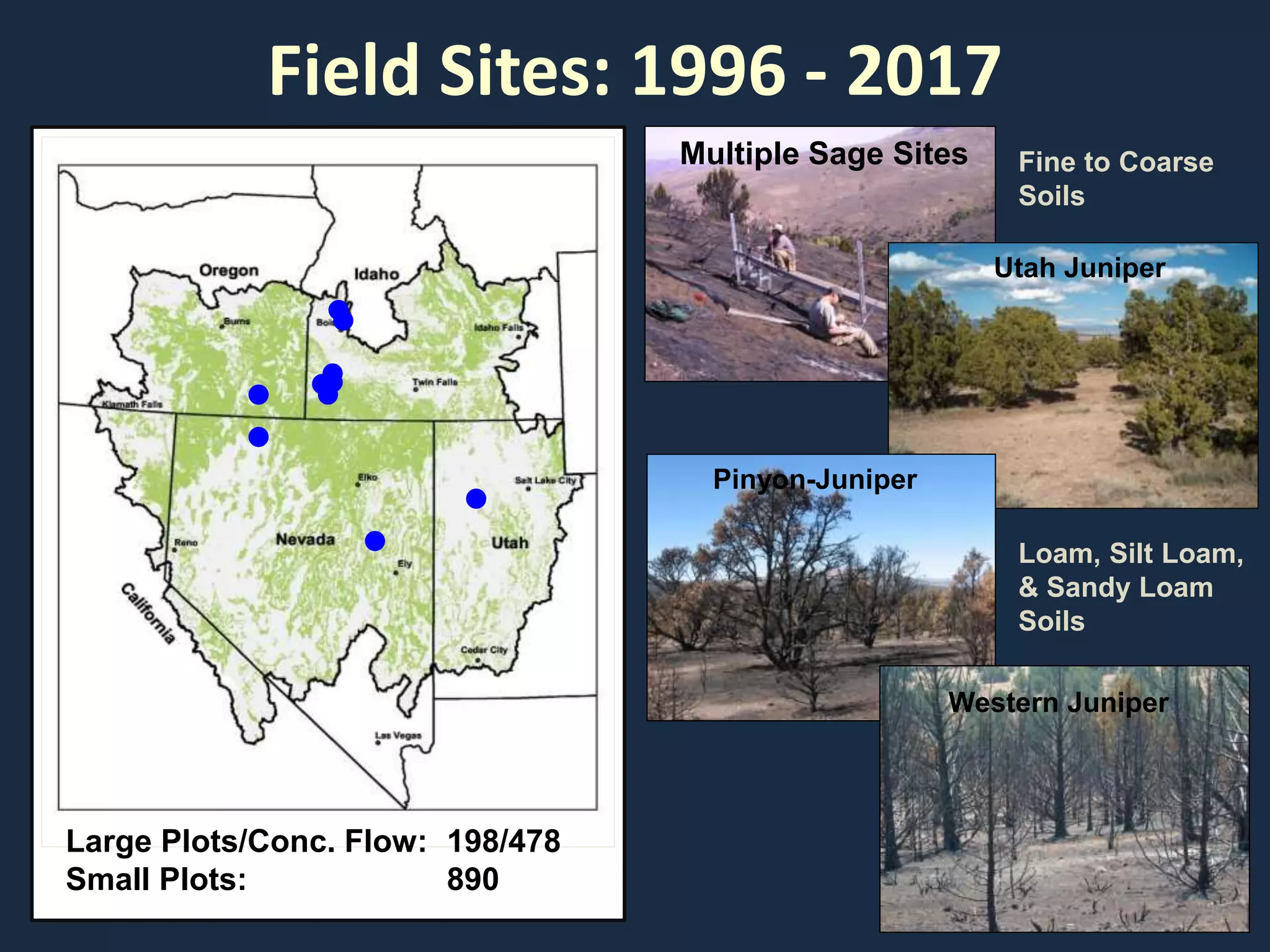

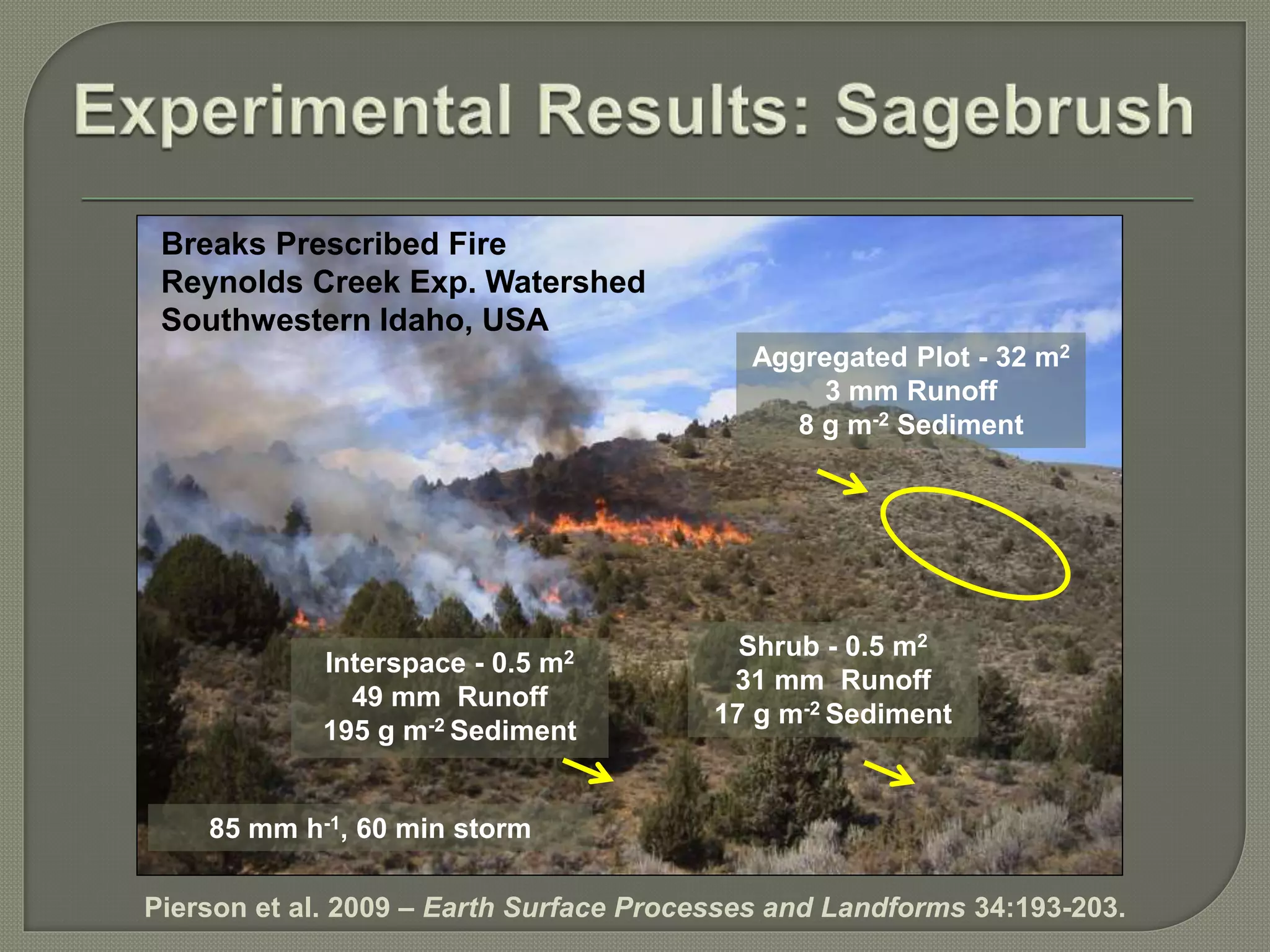

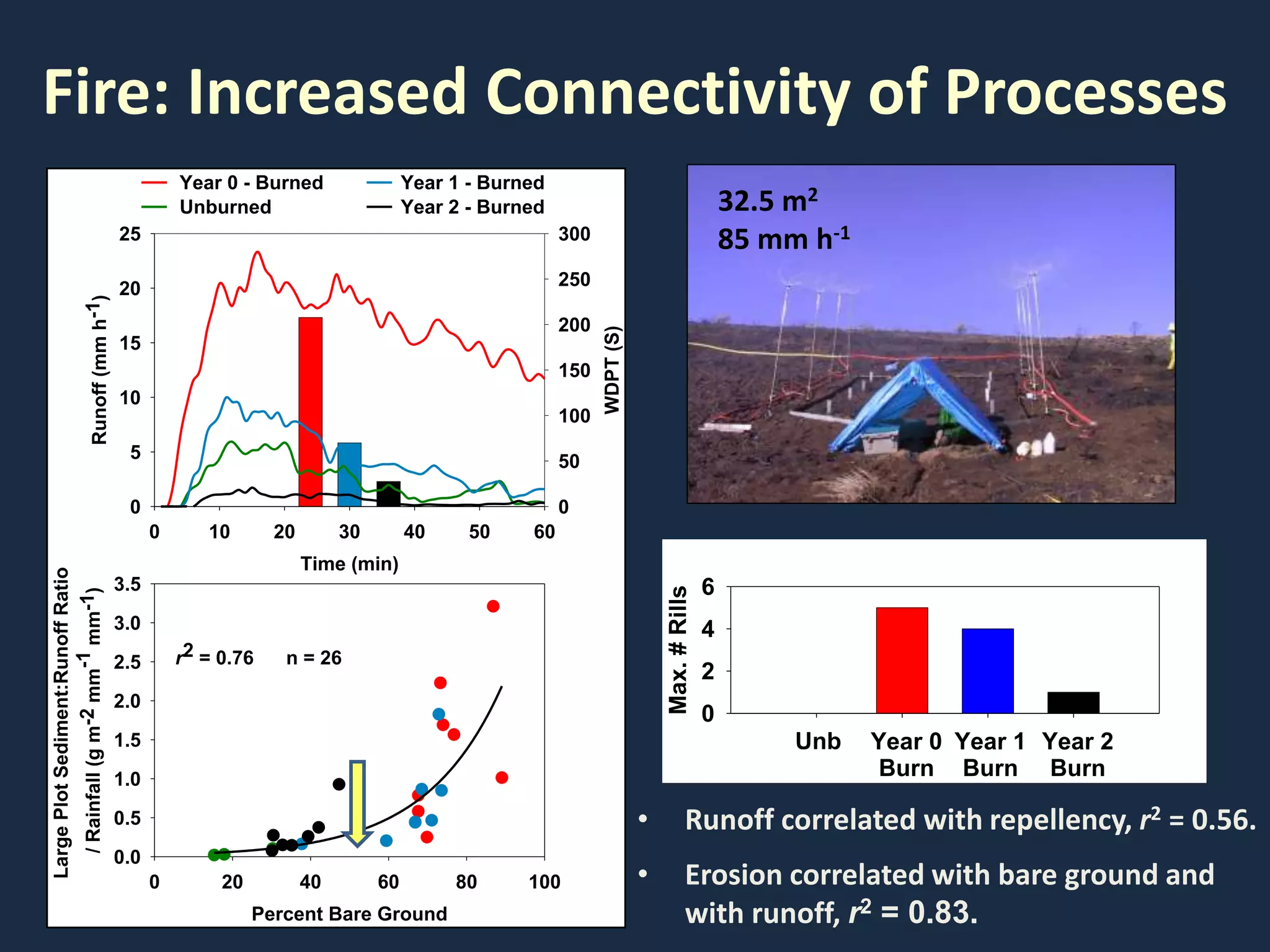

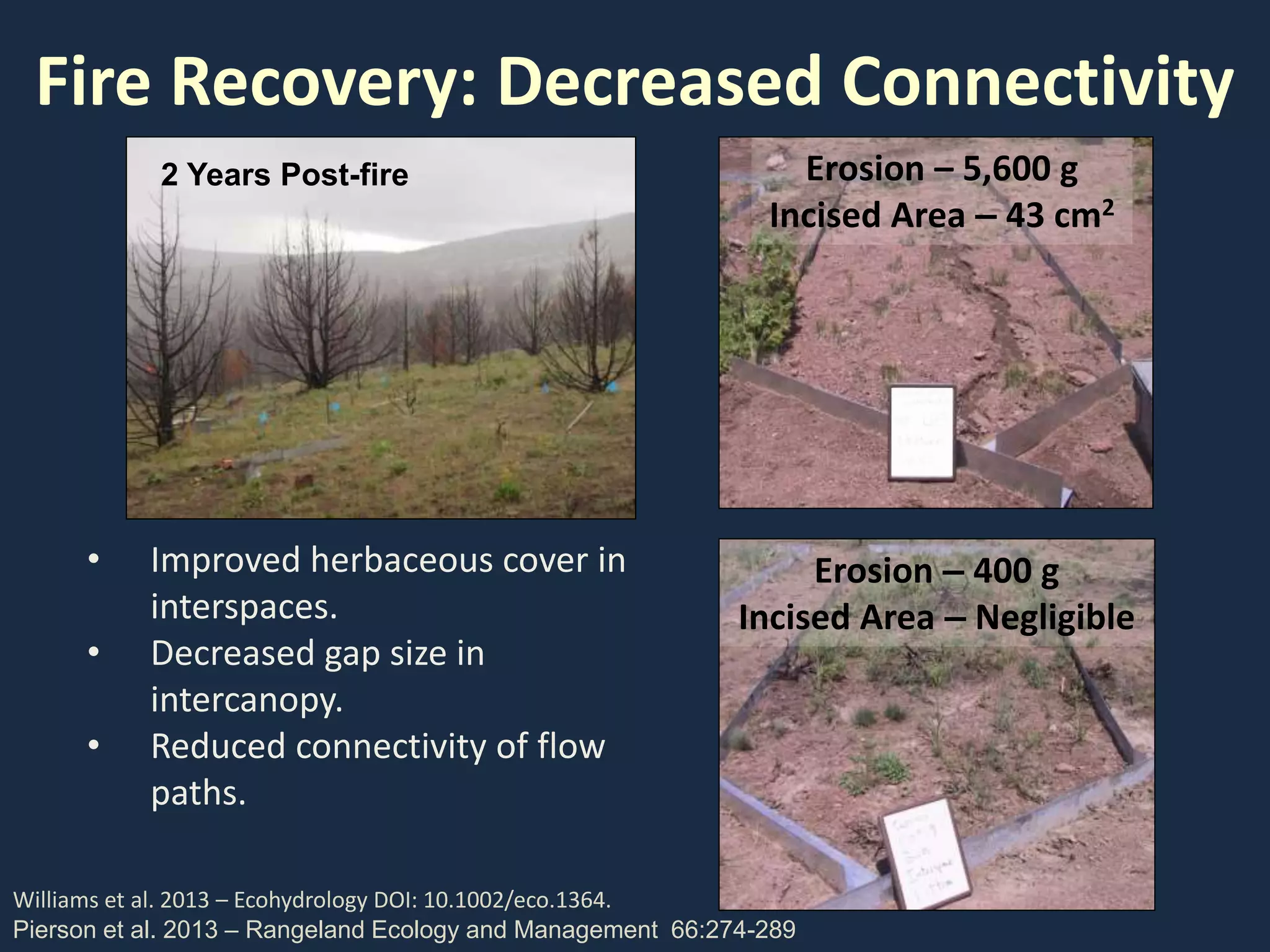

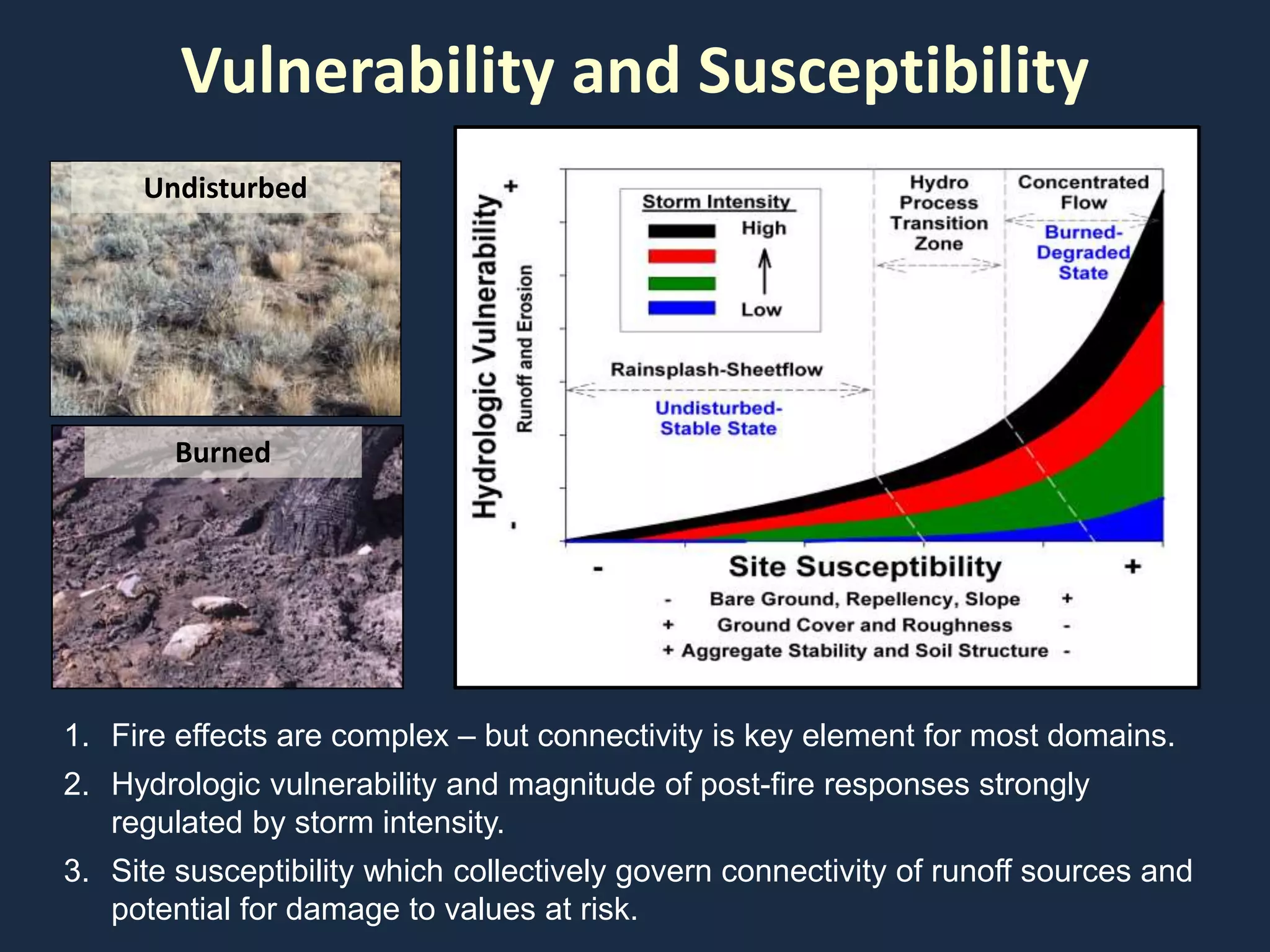

This document discusses research on the impacts of fire on rangeland hydrology and erosion processes in the western United States. The goals are to improve understanding of disturbance impacts, develop tools to predict effects on hydrologic and erosion processes, and provide guidance to land managers. Field research was conducted from 1996-2017 on sites dominated by sagebrush, pinyon-juniper, and western juniper in Idaho, Utah, Nevada and other states. Results show that fire increases connectivity of overland flow paths and sediment delivery. Recovery occurs as vegetation reduces bare ground and connectivity over multiple growing seasons.