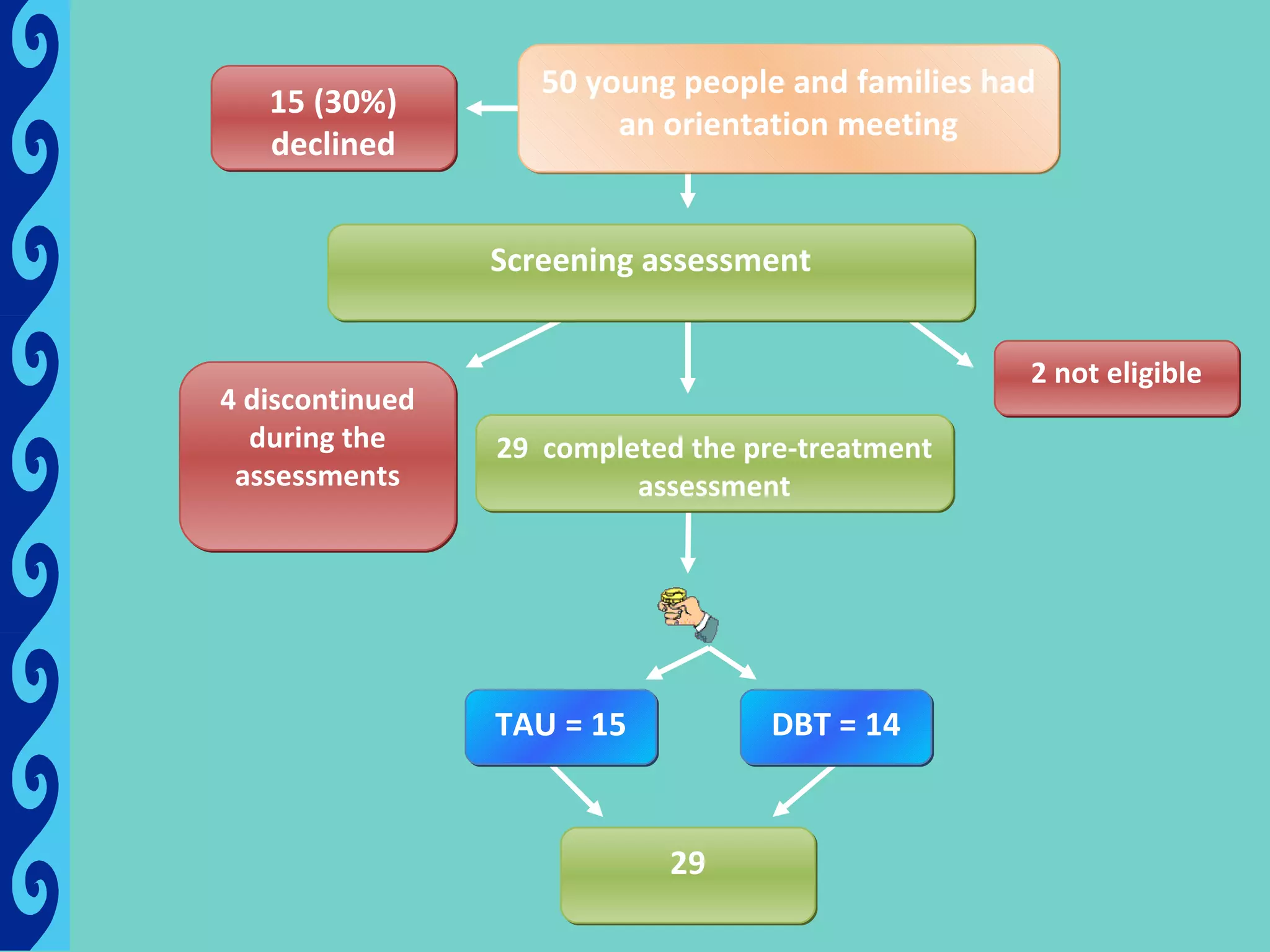

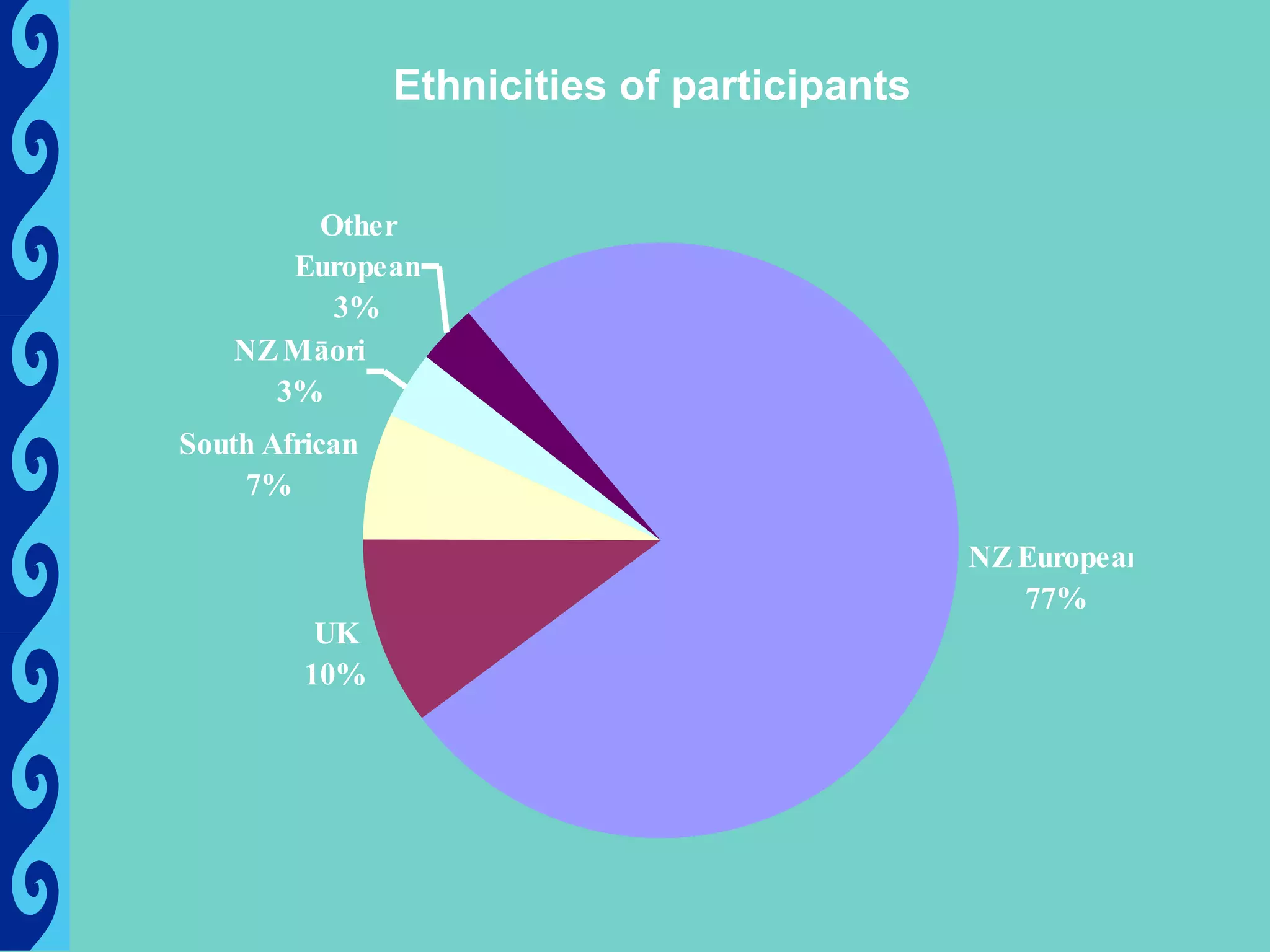

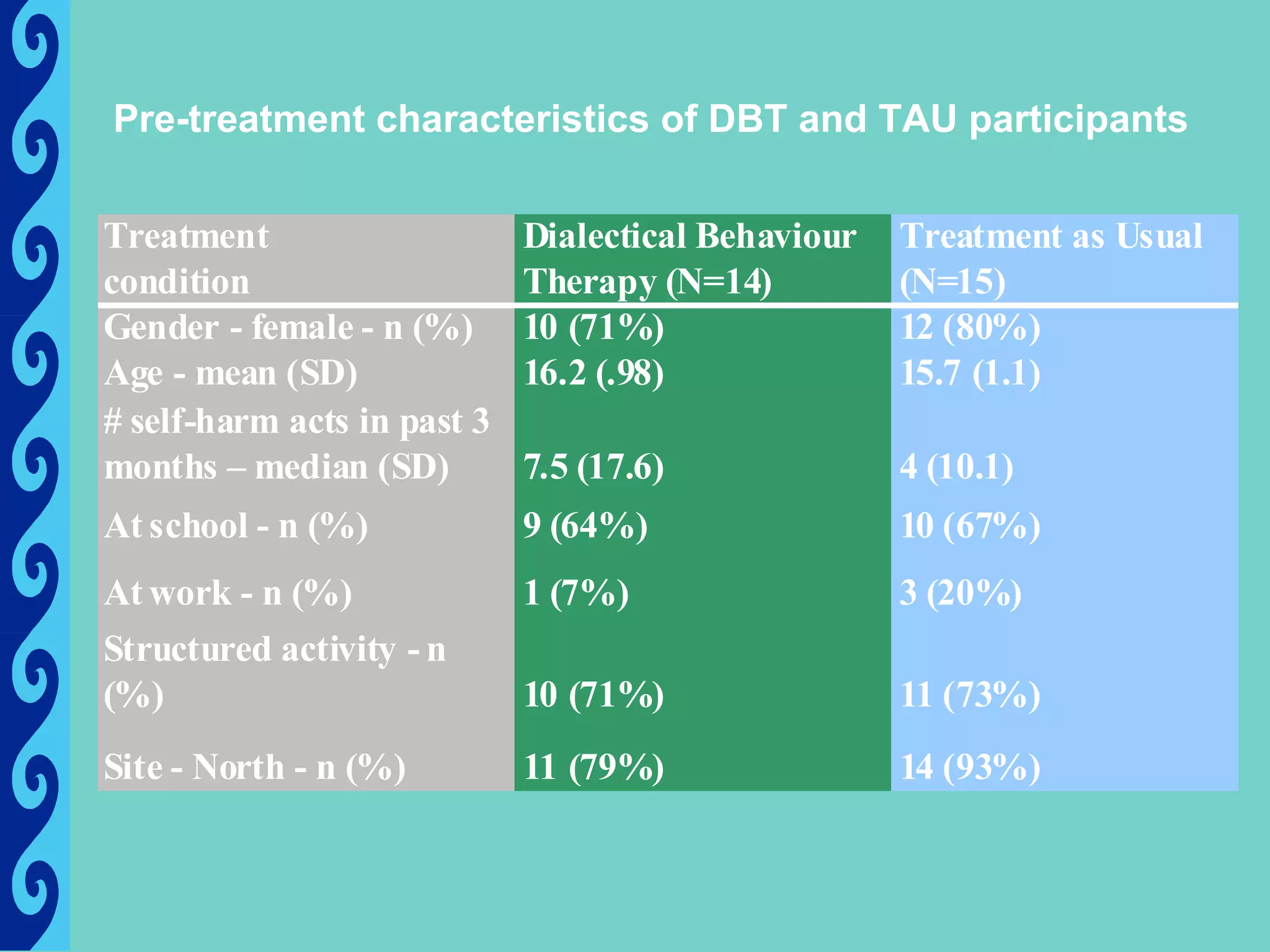

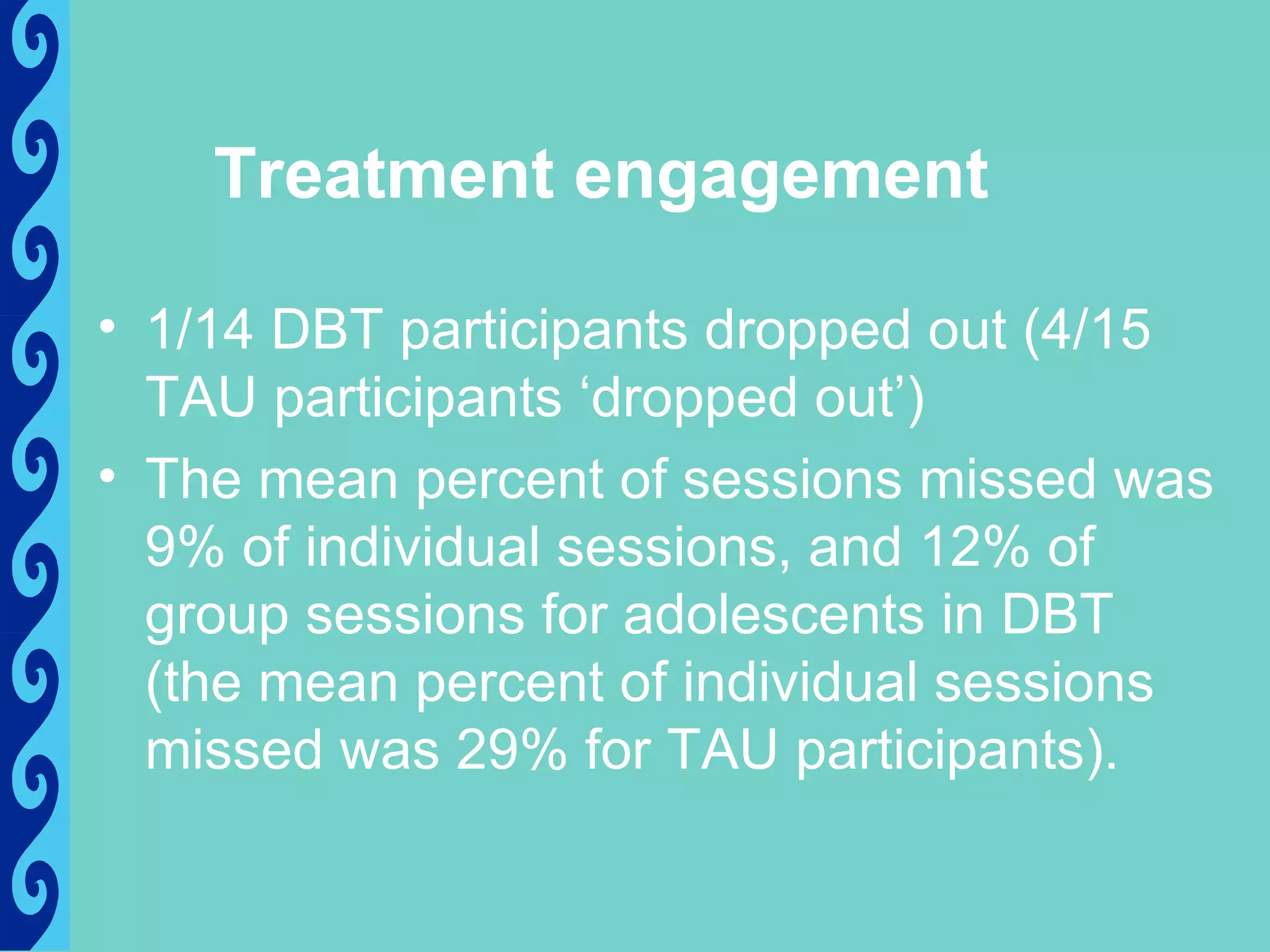

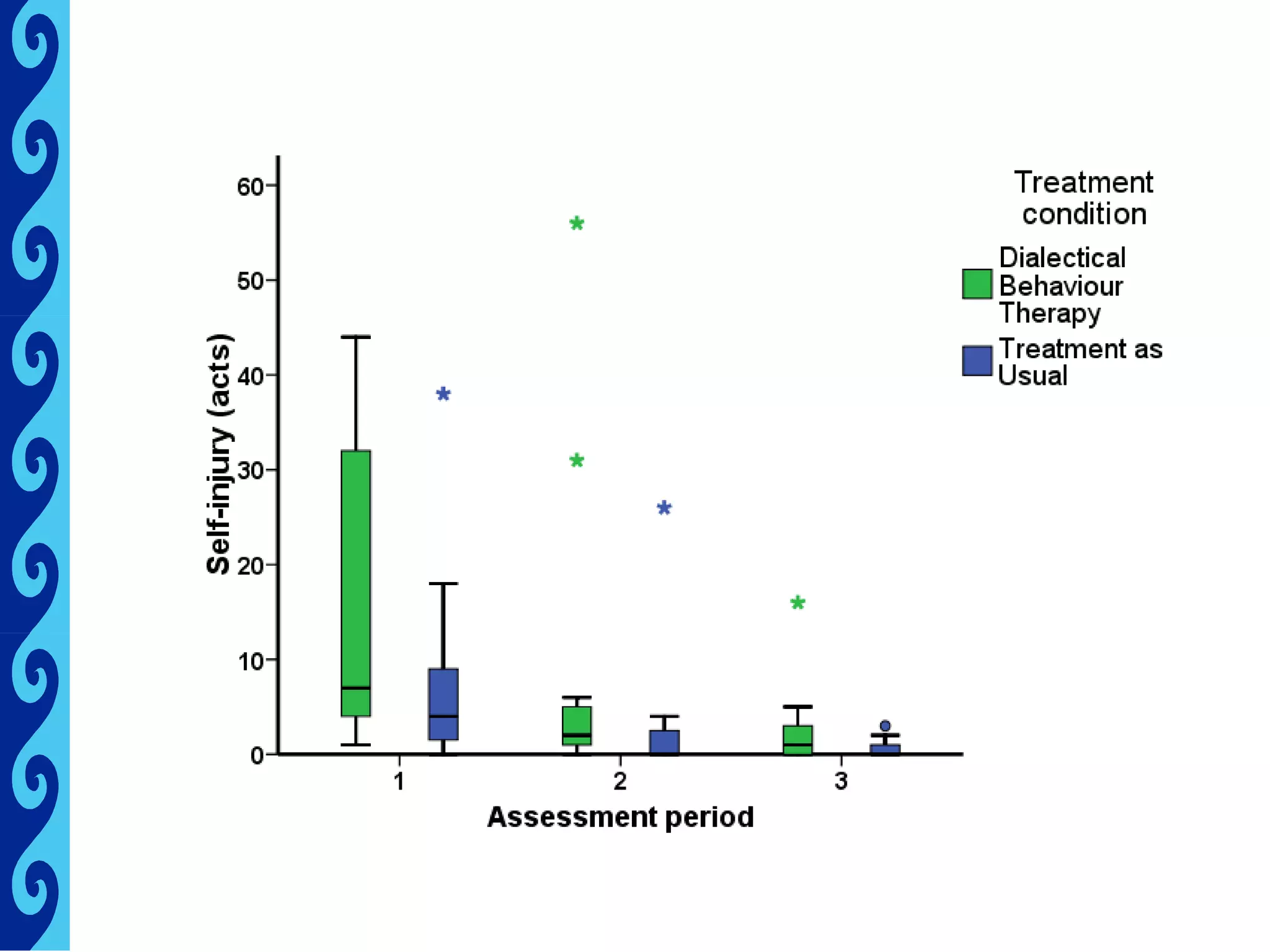

This document discusses the feasibility of researching dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) for suicidal and self-injuring adolescents in New Zealand, highlighting the need for effective treatments for self-harm. It raises important feasibility questions regarding the acceptability of DBT and random assignment among adolescents and their families, and presents initial engagement data from participants enrolled in the study. The findings suggest the potential for DBT to be a valuable treatment option, although the study is limited by small sample sizes and variable assessment times.