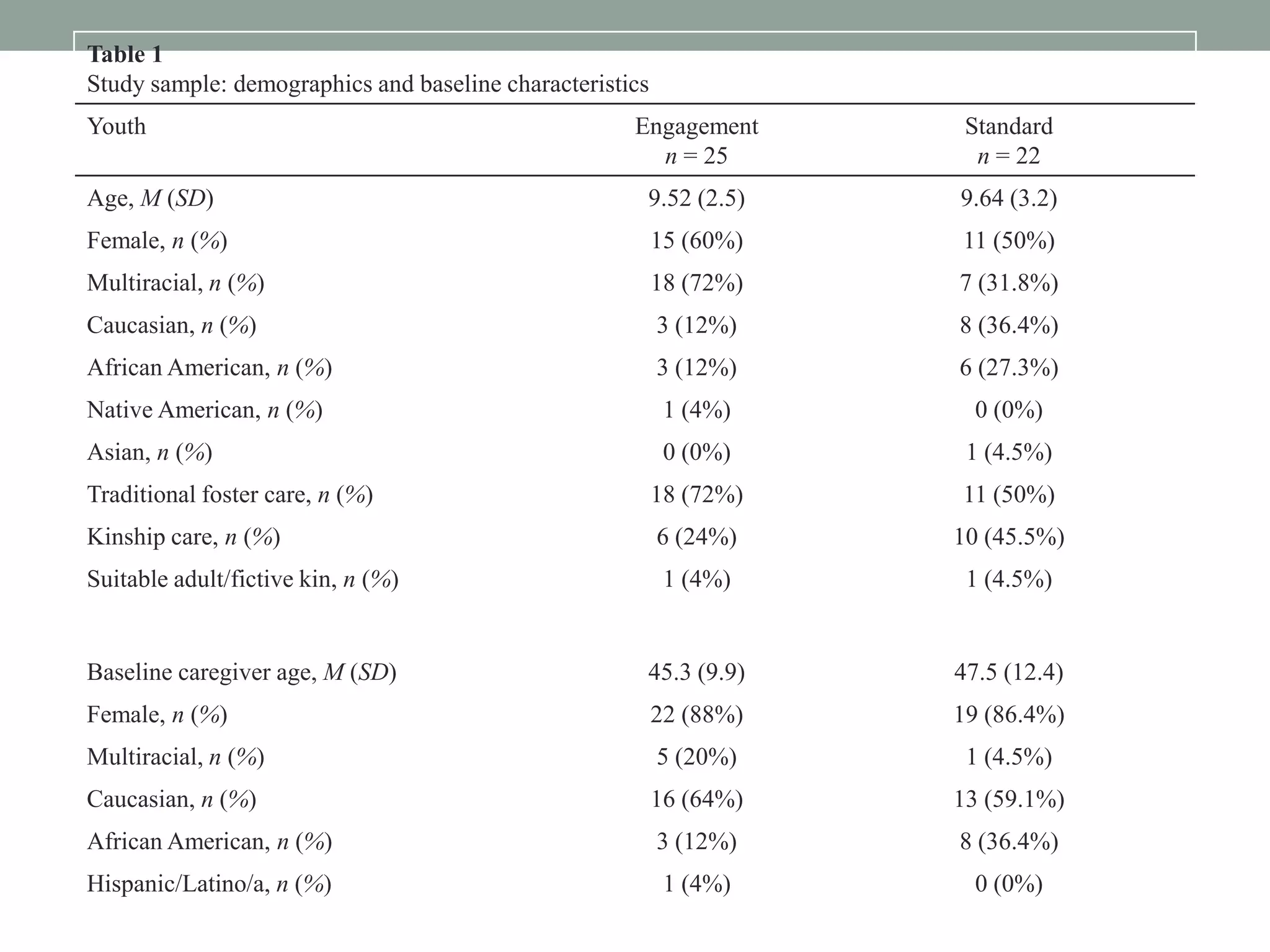

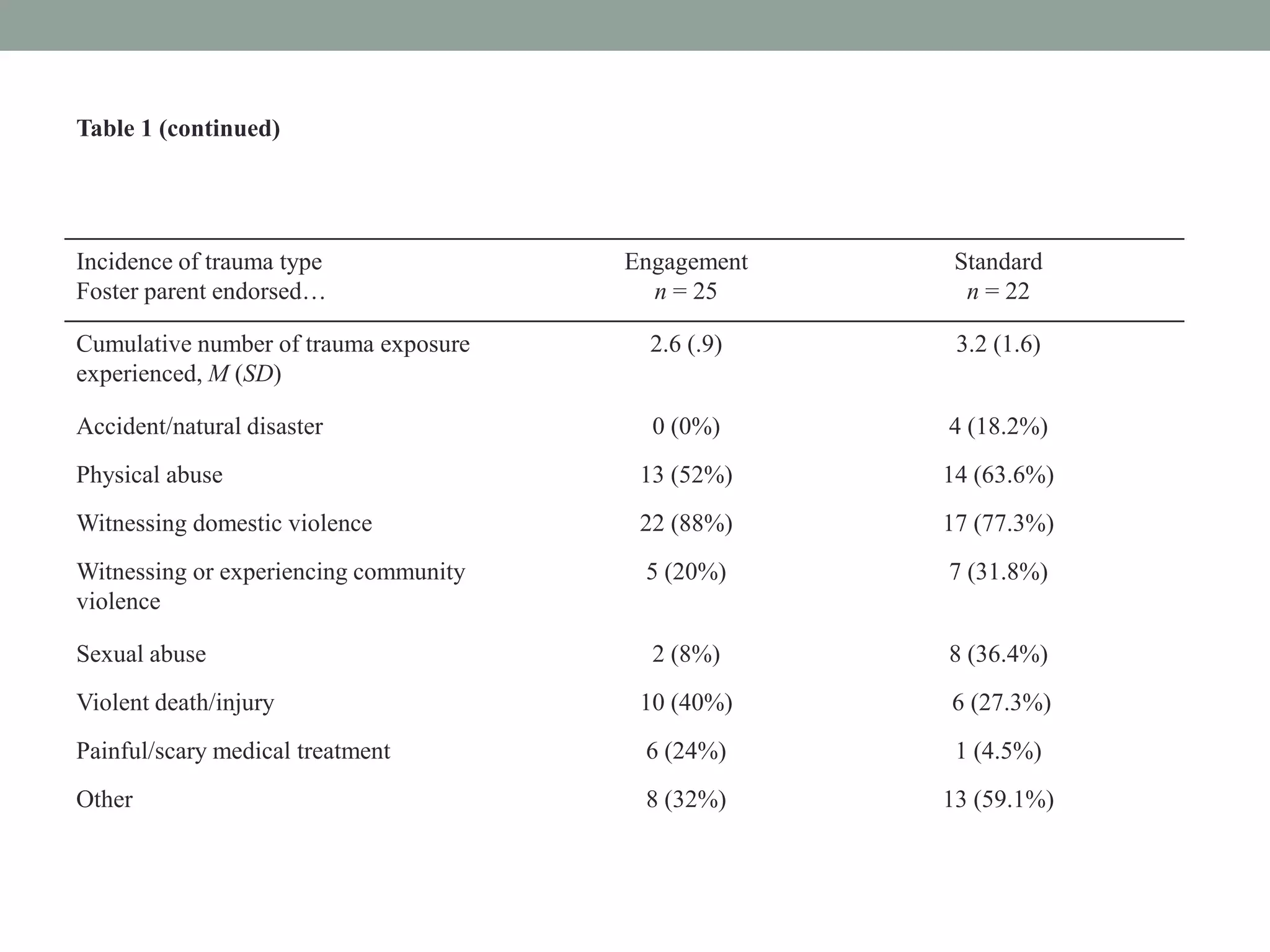

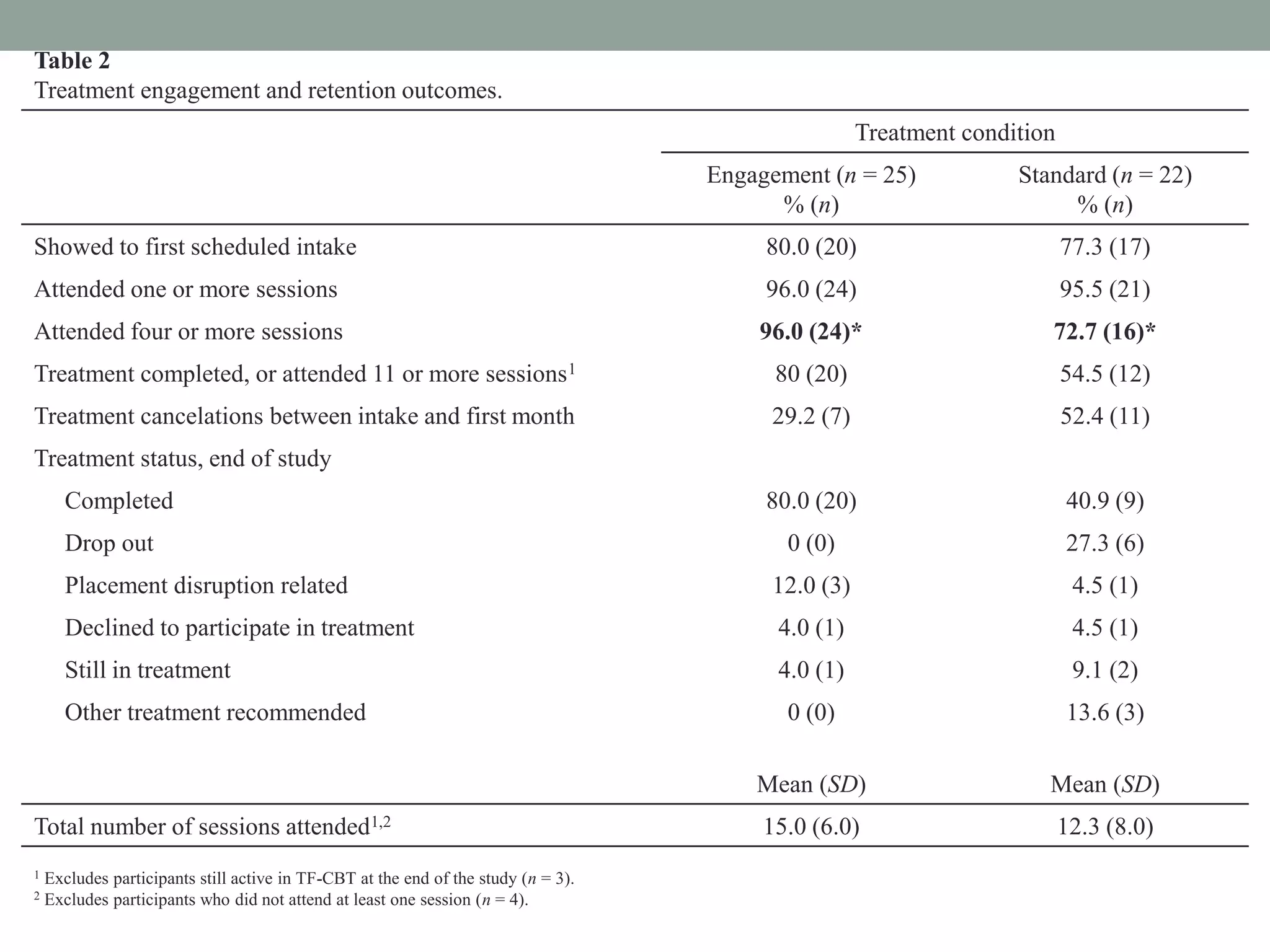

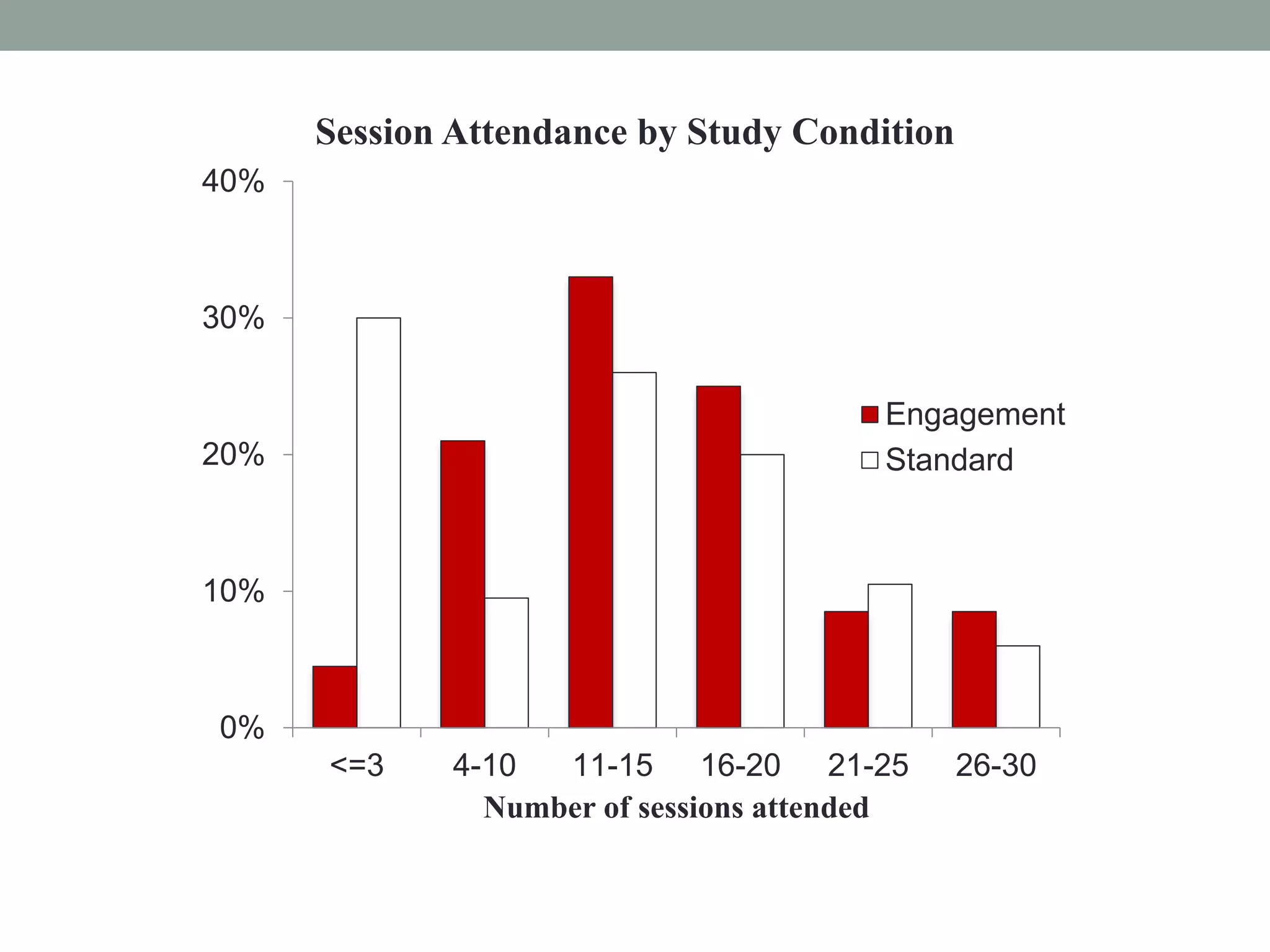

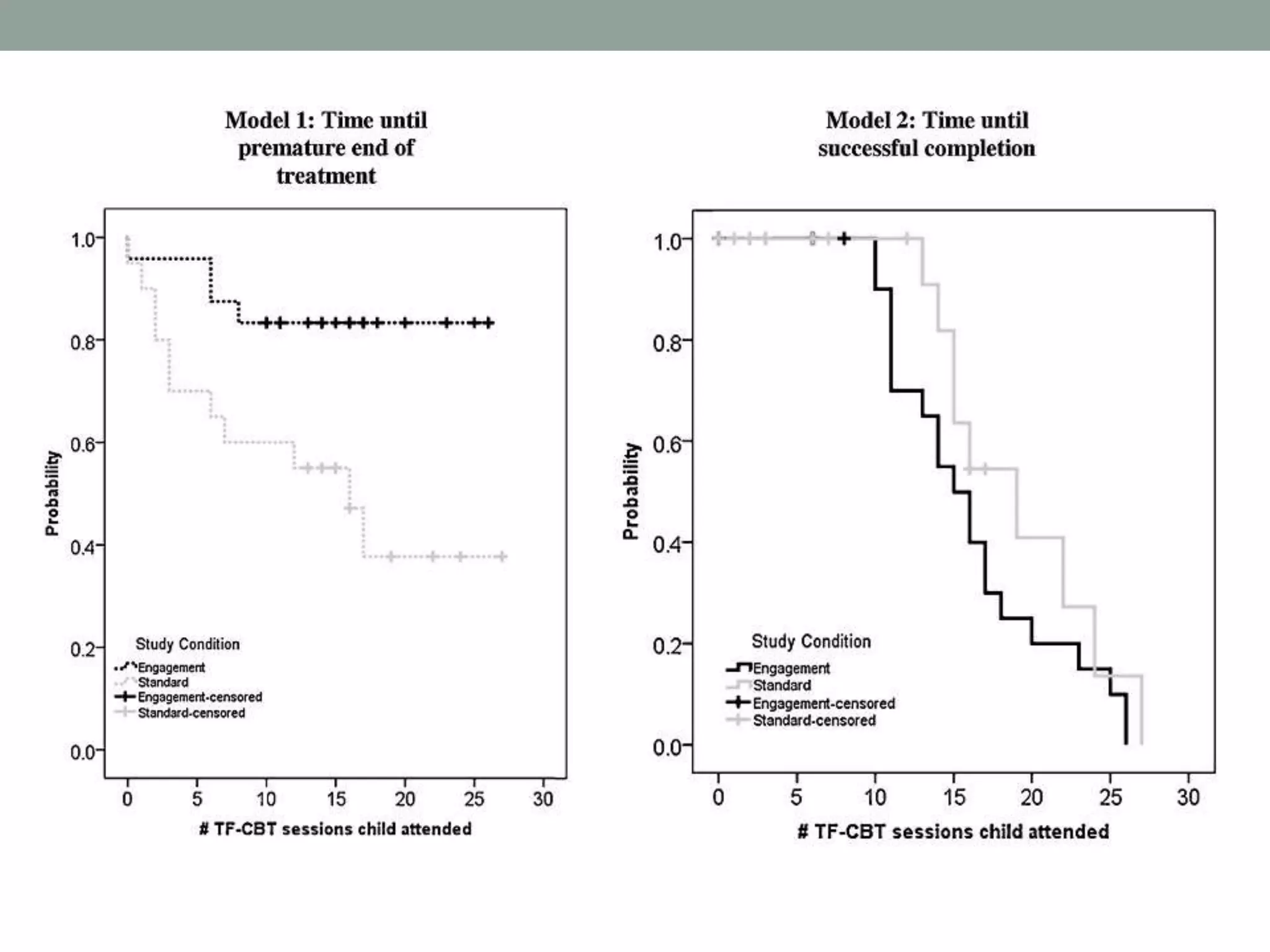

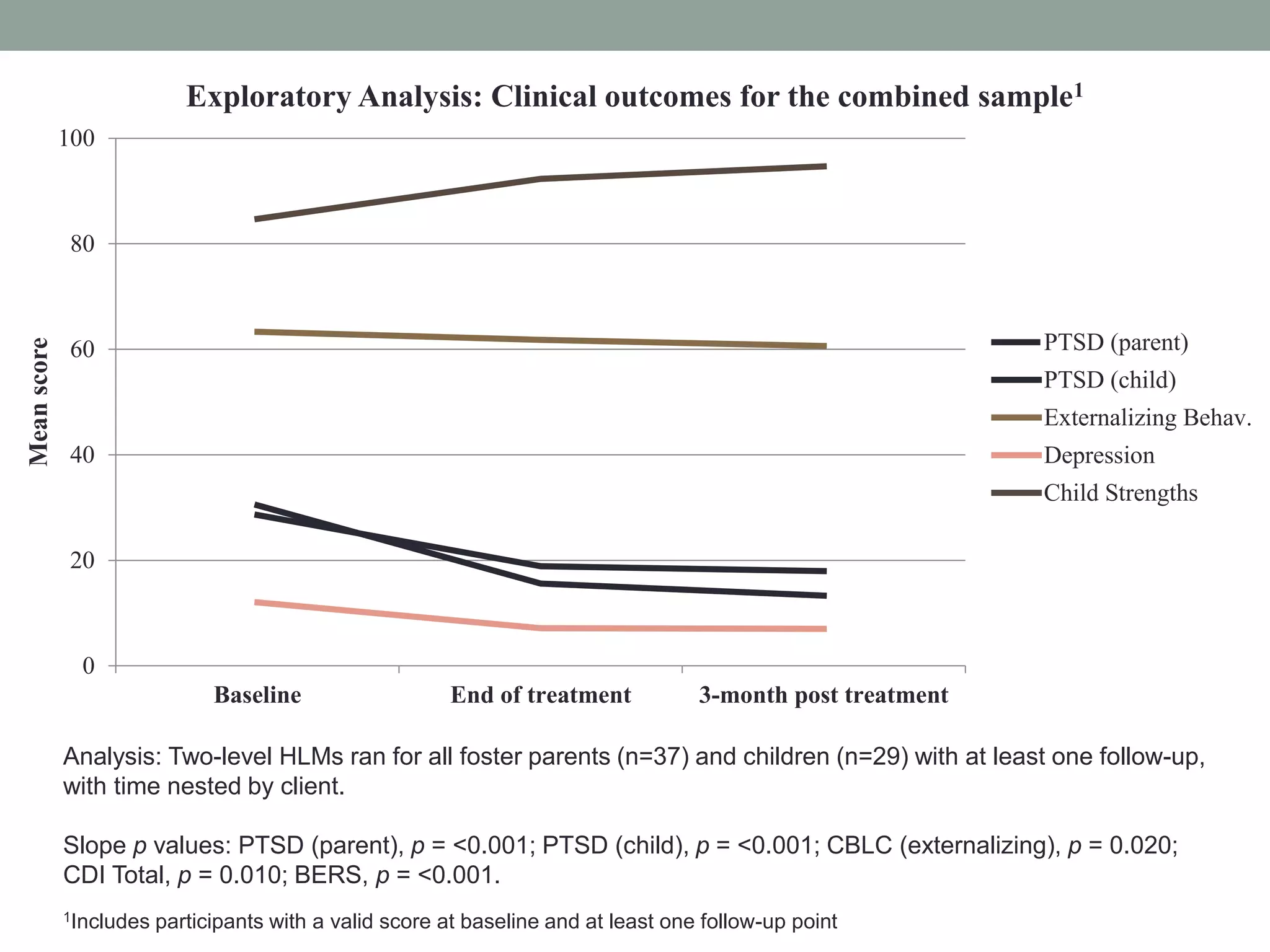

The document presents a randomized trial comparing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) with and without additional engagement strategies for foster parents. Findings indicate that engagement strategies significantly improved participation rates in active treatment sessions, with foster parents in the engagement group attending more sessions and being less likely to drop out. However, clinical outcomes showed no significant differences between the two groups, suggesting that while engagement supports attendance, it does not necessarily lead to improved results in therapy.