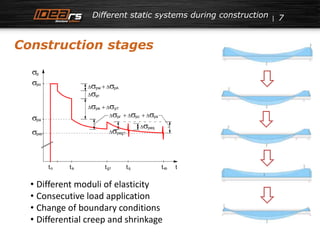

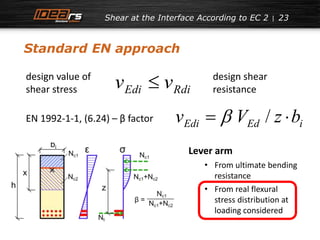

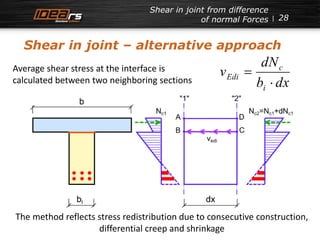

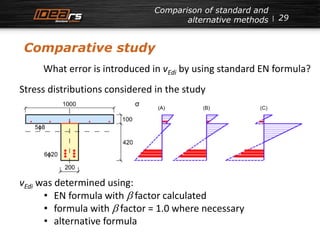

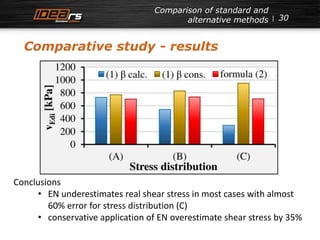

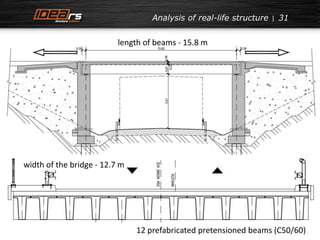

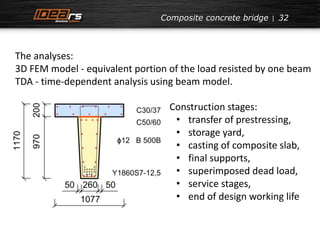

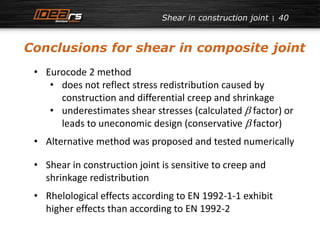

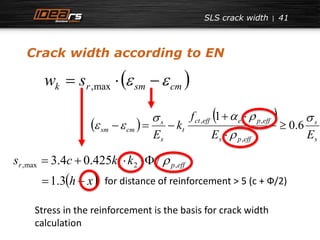

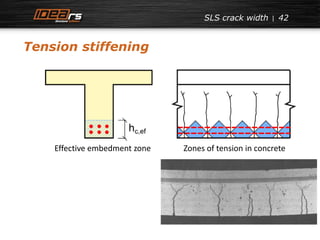

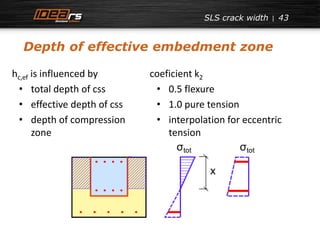

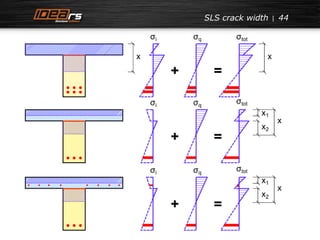

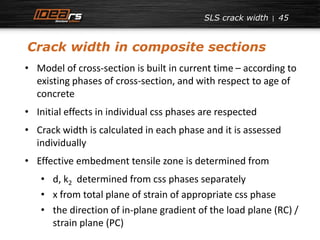

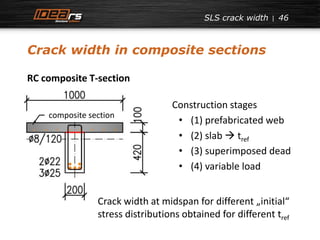

The document presents an analysis of the design of composite concrete structures, focusing on ultimate limit states such as flexure, shear, and torsion. It highlights the shortcomings of current standards (EN) in predicting shear stresses and proposes an alternative method that incorporates stress redistribution effects. Additionally, it discusses crack width calculations and emphasizes the need for a more efficient design tool for engineers.

![33

shear stresses at distance

1.1 m from support

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Shear stress [kPa]

Shear force [kN]

β-2 dx-2

β = 1,0

β ≤ 1,0

cracks

β=0,57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ec2designofcomposite-141215043432-conversion-gate01/85/Eurocode-2-design-of-composite-concrete-33-320.jpg)

![34

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

β-2 dx-2

β-1-1 dx-1-1

β = 1,0

EN 1992-1-1

100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Shear stress [kPa]

Shear force [kN]

β = 1,0

β ≤ 1,0

cracks

cracks

β=0,57

EN 1992-2

shear stresses at distance

1.1 m from support](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ec2designofcomposite-141215043432-conversion-gate01/85/Eurocode-2-design-of-composite-concrete-34-320.jpg)

![35

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

dx-1-1 dx-2

β-1-1 β-2

dx no cr-2 dx lin-2

dx lin-1-1

shear stresses at distance

100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Shear stress [kPa]

Shear force [kN]

cracks

cracks

1.1 m from support](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ec2designofcomposite-141215043432-conversion-gate01/85/Eurocode-2-design-of-composite-concrete-35-320.jpg)

![36

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

0

-1

-2

-3

σc,b-2

σc,b-1-1

σs,t-2

σs,t-1-1

normal stresses at distance

1.1 m from support

1 10 100 1000 10000 100000

Steel stress [MPa]

Concrete stress [MPa]

Age of prefabricated beam [days]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ec2designofcomposite-141215043432-conversion-gate01/85/Eurocode-2-design-of-composite-concrete-36-320.jpg)

![Casting of composite slab after 20 years 37

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0

-0.5

-1

-1.5

-2

1 10 100 1000 10000 100000

Steel stress [MPa]

Concrete stress [MPa]

Slab age [days]

σc,b-2

σc,b-1-1

σs,t-2

σs,t-1-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ec2designofcomposite-141215043432-conversion-gate01/85/Eurocode-2-design-of-composite-concrete-37-320.jpg)

![Casting of composite slab after 20 years 38

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

dx-1-1 dx-2

β-1-1 β-2

dx lin-1-1 dx lin-2

β = 1,0

cracks cracks

100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Shear stress [kPa]

Shear force [kN]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ec2designofcomposite-141215043432-conversion-gate01/85/Eurocode-2-design-of-composite-concrete-38-320.jpg)

![39

Comparison composite slab after

60 days/20 years

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

dx 60 days-2

dx 60 days-1-1

dx 20 years-2

dx 20 years-1-1

100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Shear stress [kPa]

Shear force [kN]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ec2designofcomposite-141215043432-conversion-gate01/85/Eurocode-2-design-of-composite-concrete-39-320.jpg)

![SLS crack width

Crack width in composite sections

51

RC composite T-section (after 100 years)

Casting of composite slab [days]

Crack in slab [mm]

Crack in web [mm]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ec2designofcomposite-141215043432-conversion-gate01/85/Eurocode-2-design-of-composite-concrete-51-320.jpg)