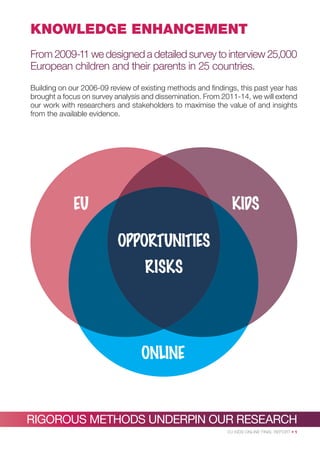

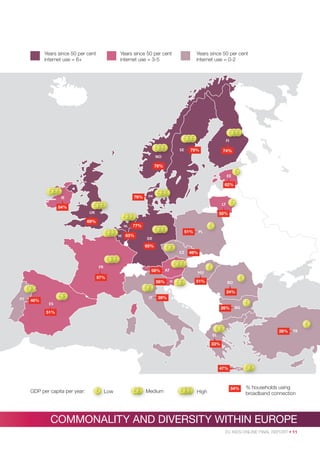

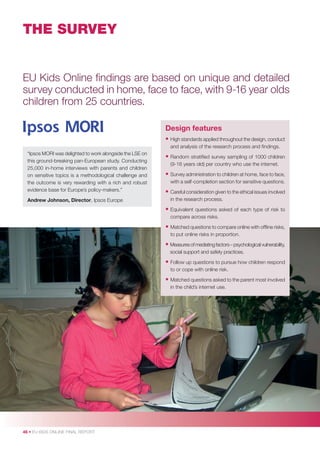

The EU Kids Online project aimed to enhance knowledge about European children's experiences with and practices regarding risky and safer internet use. It conducted a detailed survey interviewing 25,142 9-16 year old internet users and their parents from 25 countries in 2010. The purpose was to provide rigorous evidence to support stakeholders' efforts to maximize online opportunities for children while minimizing risks of harm. The project analyzed the survey data from 2011-2014 to provide insights and evidence to inform policymaking.

![25,142 children interviewed during Spring and Summer 2010

Survey administration

The survey was commissioned through a public tender process. It

was conducted by Ipsos MORI, working with national agencies in

each country. The EU Kids Online team designed the sample and

questionnaire, and worked closely with Ipsos MORI throughout

pre-testing (cognitive testing, piloting), translation, interviewer

briefings, and the fieldwork process.

The design allows comparisons of

children’s online experiences...

• Across locations and devices.

• By child’s age, gender and SES.

• Of pornography, bullying, sexual messaging,

meeting strangers.

Technical report and questionnaires

These can be freely downloaded from the project website.

Researchers may use the questionnaires, provided they inform

the Coordinator (LSE), and acknowledge the project as follows:

“This [article/chapter/report/presentation/project] draws on the

work of the ‘EU Kids Online’ network funded by the EC (DG

Information Society) Safer Internet Programme (project code

SIP-KEP-321803); see www.eukidsonline.net”

• In terms of children’s roles as ‘victim’ and ‘perpetrator’.

• Of encounters with risk versus perceptions of harm.

• Of online and offline risks.

• Of risk and safety as reported by children and by

their parents.

• Across 25 countries.

The dataset

All coding and analysis of the dataset has been conducted by

the EU Kids Online network. Crosstabulations of key findings

are available at www.eukidsonline.net. The full dataset

(SPSS raw file, with data dictionary and all technical materials)

is being deposited in the UK Data Archive for public use.

www.data-archive.ac.uk/

RIGOROUS METHODS UNDERPIN OUR RESEARCH

EU KIDS ONLINE FINAL REPORT • 47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/final20report-140115045715-phpapp01/85/EU-kids-online-report-49-320.jpg)