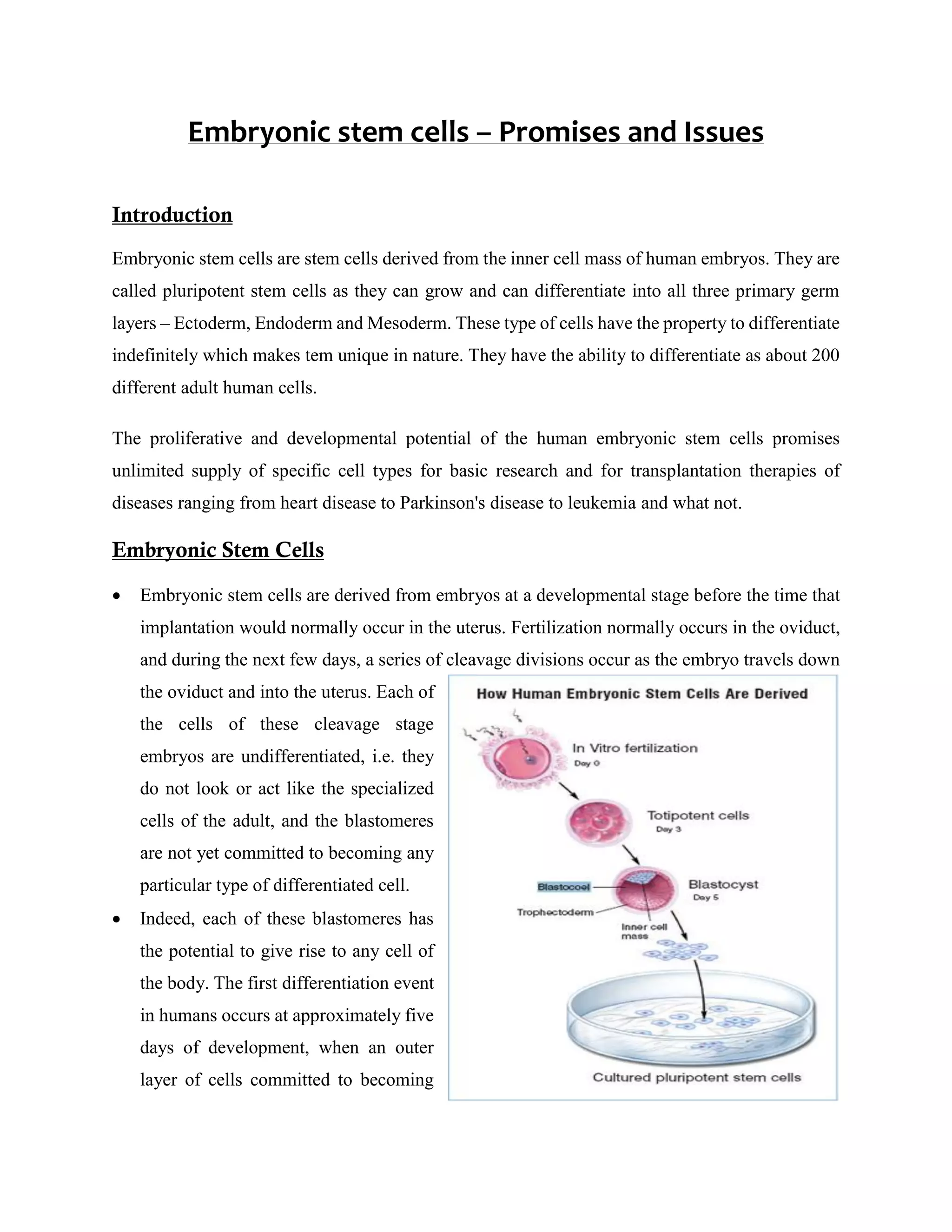

Embryonic stem cells, derived from the inner cell mass of human embryos, hold immense potential for research and therapy, capable of differentiating into any adult cell type and offering a pathway to treat various diseases. However, ethical concerns regarding their use, including informed consent and the handling of frozen embryos from infertility treatments, complicate the research landscape. While promising for cell replacement therapies and wider biological studies, the political climate and funding restrictions significantly challenge the pace of advancements in stem cell research.