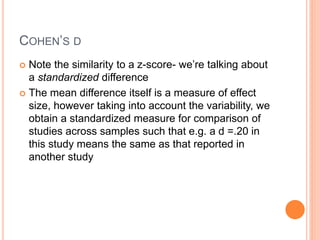

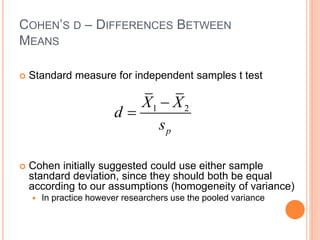

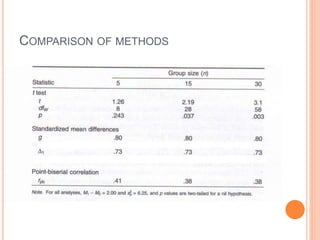

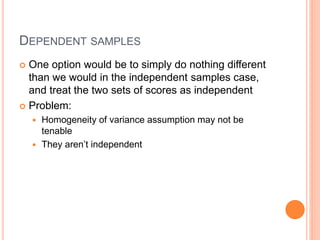

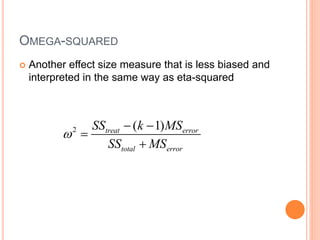

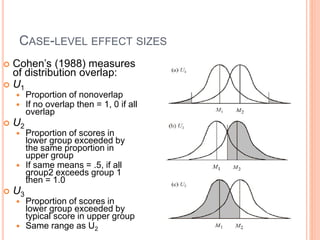

This document discusses effect size and its importance in statistical analysis over solely relying on statistical significance. It defines various types of effect sizes including Cohen's d for standardized mean differences, eta-squared and omega-squared for variance explained, and odds ratios. Guidelines are provided for interpreting small, medium, and large effect sizes. Methods for calculating effect sizes are outlined for independent and dependent sample designs. The document stresses that effect sizes provide valuable information about the practical significance and real-world impact of study findings.