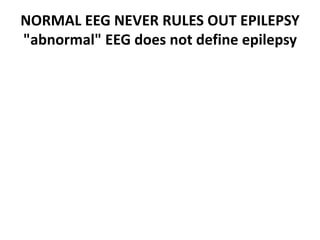

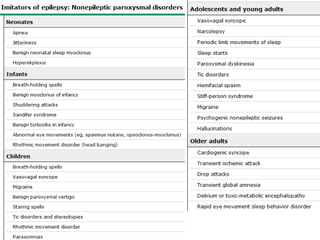

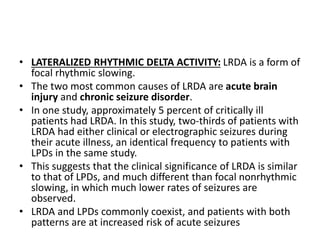

This document discusses the use and interpretation of electroencephalography (EEG) in evaluating patients for possible epilepsy. It makes several key points:

1. EEG alone cannot be used to definitively diagnose or rule out epilepsy, as abnormal EEG patterns can be caused by various neurological conditions, and not all epilepsy cases show EEG abnormalities.

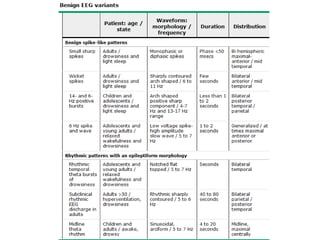

2. Certain EEG findings like interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs) are strongly associated with epilepsy, while nonspecific findings like slowing are less so.

3. The sensitivity of EEG for detecting epilepsy depends on factors like the number of studies, study duration, seizure frequency, and use of activation procedures.

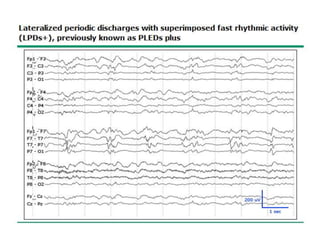

4. Specific EEG patterns like lateralized periodic

![EEG FINDINGS IN PATIENTS WITH

EPILEPSY

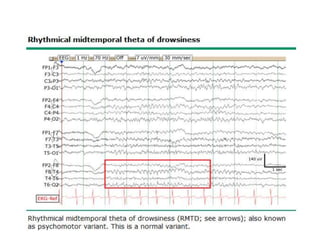

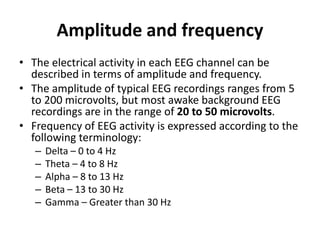

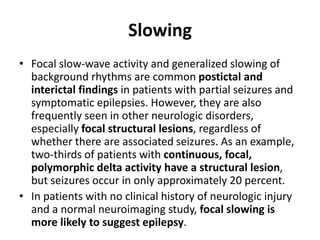

• Different EEG findings are variably associated with

epilepsy.

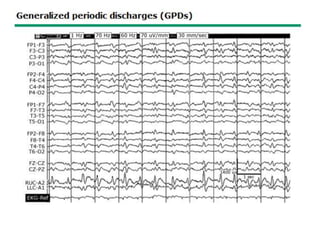

– Examples of epileptiform activity include interictal

epileptiform discharges (IEDs), lateralized periodic

discharges (LPDs; previously known as periodic lateralized

epileptiform discharges [PLEDs], and generalized periodic

discharges (GPDs).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eeg-201009135945/85/Eeg-basics-part-1-8-320.jpg)

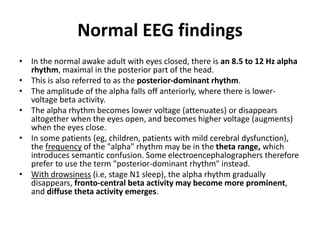

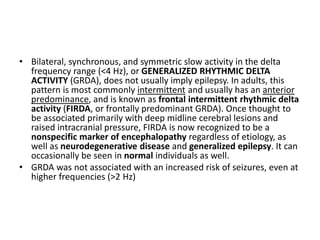

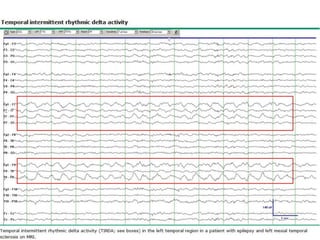

![• Occipital intermittent rhythmic delta activity (OIRDA) is more

common in young children and is rarely seen in patients older than

15 years. It is a frequent interictal finding in generalized epilepsy

syndromes, occurring in 15 to 38 percent of all patients with

childhood absence epilepsy, and implies a good prognosis.

• Temporal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (TIRDA) is a

particular form of focal slowing (and a subtype of lateralized

rhythmic delta activity [LRDA]; that is specific for temporal lobe

localization in patients with refractory epilepsy. TIRDA is observed in

as many as 25 to 40 percent of patients being evaluated for

temporal lobe resection. TIRDA is often associated with temporal

IEDs and has a high positive predictive value for temporal lobe

localization in patients with refractory epilepsy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eeg-201009135945/85/Eeg-basics-part-1-26-320.jpg)

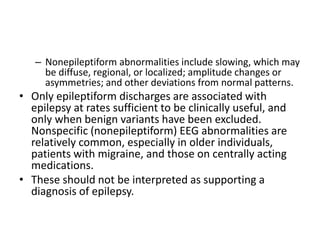

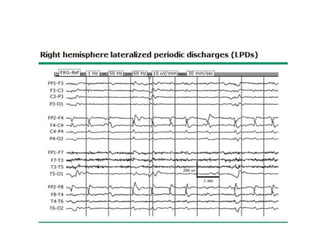

![Sleep and sleep deprivation

• Sleep is a neurophysiologic activator of epilepsy; 20 to 40 percent

of epilepsy patients with an initial normal recording will have IEDs

on a subsequent recording that includes sleep.

• Sleep is sometimes captured on a routine EEG, but sleep

deprivation increases this likelihood.

• Sleep is also usually captured on prolonged EEG monitoring and,

alternatively, can be induced by administration of a sedative,

usually chloral hydrate.

• Sleep deprivation appears to increase IEDs to an extent not fully

explained by the greater chance of recording sleep. One study

found that the additional yield of a sleep-deprived EEG was similar

whether or not sleep was recorded [83].

• The sleep-deprived patients were also more likely to have a seizure

during the EEG compared with the sedated patients.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eeg-201009135945/85/Eeg-basics-part-1-34-320.jpg)