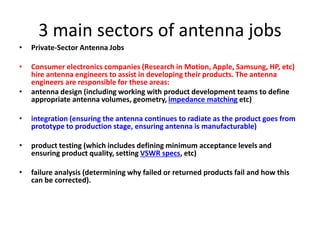

This document discusses different types of antenna jobs and areas of research. It describes three main sectors for antenna jobs: private sector working for consumer electronics companies, defense department/government jobs, and university/research jobs. It provides details on the responsibilities for each type of private sector job and notes that defense and government jobs focus more on research and integration. University/research jobs primarily involve publishing research and involve some teaching. Active areas of antenna research mentioned include meta-materials, electromagnetic solvers, miniaturization, and array optimization.

![Electromagnetic Spectrum

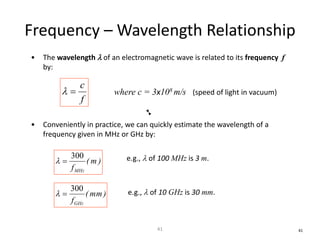

• The Electromagnetic Spectrum covers a very wide range of frequency,

from almost DC to gamma rays.

• Radio frequency (RF) is a subset of the EM spectrum and is loosely

defined as:

“The frequency in the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that is

between the audio-frequency portion and the infrared portion. The present

practical limits of radio frequency are roughly 10 kHz to 100 GHz.” [IEEE

Std 100-1988 Standard Dictionary of Electrical and Electronic Terms]

• EM (Electromagnetic) waves can propagate in vacuum but not acoustic

waves.

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/antennafundamentalsnew-converted-190714192613/85/EC6602-Antenna-fundamentals-40-320.jpg)