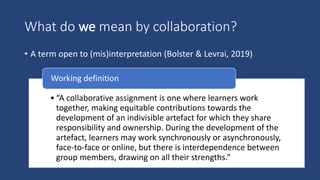

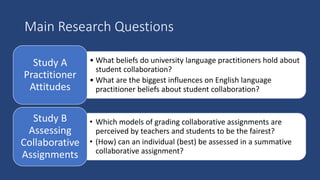

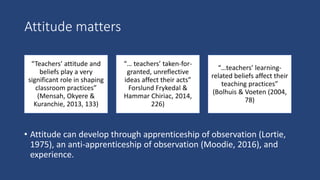

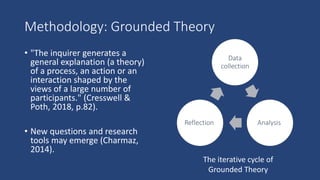

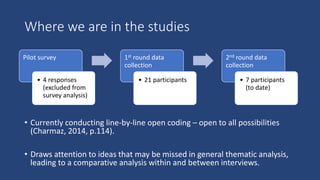

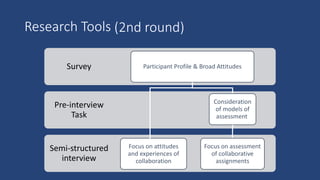

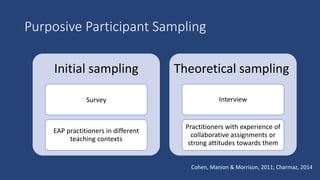

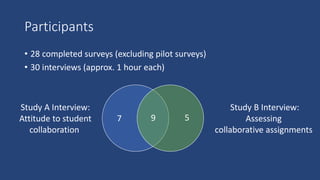

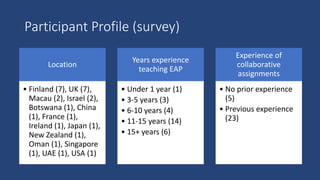

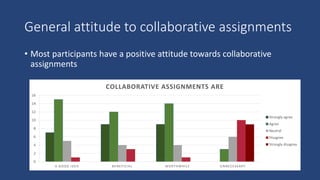

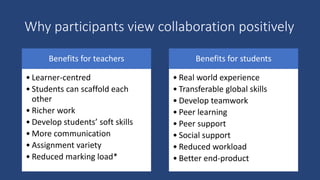

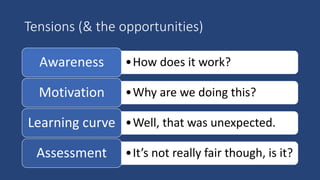

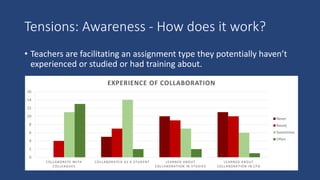

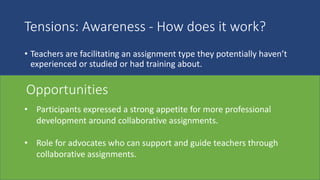

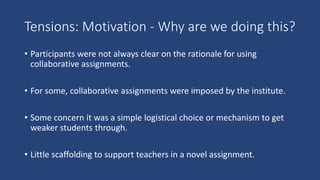

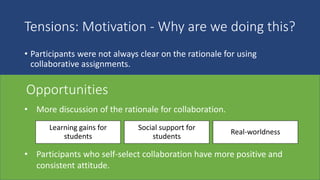

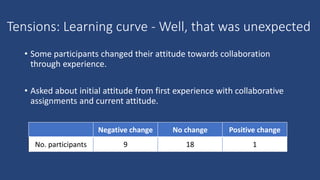

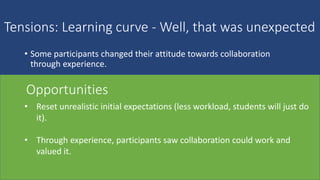

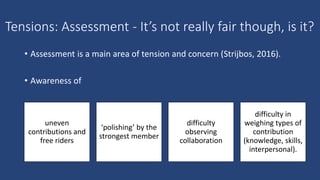

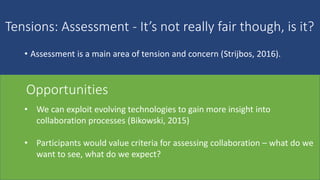

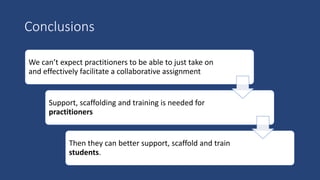

The document discusses the research on English for Academic Purposes (EAP) practitioners' attitudes towards collaborative assignments, highlighting the benefits and challenges involved in their implementation. It outlines the methodology used for data collection, key findings regarding practitioner beliefs, and the need for professional development to facilitate effective collaboration in educational settings. Overall, it emphasizes the necessity for a supportive pedagogy to enhance collaborative learning experiences for both teachers and students.