The document discusses the life and works of Italian playwright Luigi Pirandello, emphasizing his revolutionary play 'Six Characters in Search of an Author.' It explores major themes such as identity, reality versus illusion, and the impact of personal tragedy on his writing. Pirandello's oeuvre significantly influenced modern theatre, positioning him as a key figure in the development of modern drama and anti-illusionism.

![And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing.

!

In 1903 Bertrand Russell also used dramatic imagery to express his sense of an absurd universe:

!

And Man saw that all is passing in this mad, monstrous world, that all is struggling to snatch, at any

cost, a few brief moments of life before Death’s inexorable decree. And Man said: ‘There is a hidden

purpose, could we but fathom it, and the purpose is good; for we must reverence something, and in

the visible world there is nothing worthy of reverence’. And man stood aside from the struggle,

resolving that God intended harmony to come out of chaos by human efforts. And when he followed

the instincts which God had transmitted to him from his ancestry of beasts of prey, he called it Sin,

and asked God to forgive him. But he doubted whether he could be justly forgiven, until he inverted a

divine Plan by which God’s wrath was to have been appeased. And seeing the present was bad, he

made it still worse, that thereby the future might be better. And he gave God thanks for the strength

that enabled him to forgo even the joys that were possible. And God smiled; and when he saw that

Man had become perfect in renunciation and worship, he sent another sun through the sky, which

crashed into Man’s sun; and all returned again to nebula. ‘Yes’, he murmured, ‘it was a good play; I

will have it performed again’. [A Free Man’s Worship]

!

Pirandello also indicts God for creating sentient beings and denying them a purpose in his image, in

the final paragraph of his preface, of the playwright as deus absconditus:

Though the audience eventually understands that one does not create life by artifice and that the

drama of the six characters cannot be presented without an author to give them value with his spirit,

the Manager remains vulgarly anxious to know how the thing turned out, and the ‘ending’ is

remembered by the son in its sequence of actual moments, but without any sense and therefore not

needing a human voice for its expression. It happens stupidly, uselessly, with the going-off of a

mechanical weapon on stage. It breaks up and disperses the sterile experiment of the characters and

the actors, which has apparently been made without the assistance of the poet. The poet, unknown to

them, as if looking on at a distance during the whole period of the experiment, was at the same time

busy creating – with it and of it – his own play. (Keith Sagar)

!

RAISON D’ÊTRE

!

Raison d’être is a french phrase meaning reason or justification of existence. And according to Oxford

Dictionary of Literary Terms, existentialism is a current in European philosophy distinguished by its emphasis

!8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-10-2048.jpg)

![framing action. Thus Six Characters in Search of an Author concerns a play in the making which is never

finished. Each in His Own Way provides a partial but incomplete text, a work purposely left unendcd. In

Tonight We Improvise the play reaches resolution but not according to the original intent of the director-

playwright: the text literally becomes the actors. All the theater plays, however, dramatize a dialectic of

conflict. In Six Characters this dialectic is played out between the characters and the actors, between art and

life. In Each in His Own Way spectators and actors collide as “real” and “fictional" characters encounter each

other, representing fluidity and fixity, reality and illusion. In Tonight We Improvise the struggle for control of

the dramatic material is played out between the director, his actors, and the “truth" contained in the story and

its characters. In all three plays theatrical form is subjected to Pirandellian concepts of relativity and

multiplicity, for the plays tear down conventions, spatial barriers, and the walls separating action and

audience, characters and people.

!

A representative figure, the Father of Six Characters is quintessential Pirandellian in his struggle to

control passion through reason. The Father is equally a cerebral and an emotive creation who expresses a

gamut of feelings including self-confidence, torment, wit, anger, and condescension. He also personifies the

mask of remorse imposed upon him by the playwright as his defining passion. Criticized, like many of the

dramatist’s raisonneurs, for excessive philosophizing, the Father reacts by declaring the “reasons of [his]

suffering." His emphasis on the rational places him squarely in a Pirandellian universe but outside the

traditions of melodrama, where emotions are not given an intellectual structure. As commonly occurs in

Pirandellian drama, thought and emotion are fused, not divided, in the character. The act of passionate

reflection is a fundamental quality of the dramatist’s protagonists. Propelling the action of Six Characters, the

Father is the story’s prime mover, mouthpiece, advocate, and challenger. In recent years, however, literary

criticism of this play has focused more and more on the subterranean, unconscious motivations underlying the

dramatic action. Proceeding in such a psychoanalytical line, Eric Bentley remarks that the Father is the source

of the Characters’ catastrophes and the “base of that Oedipal triangle on which the family story rests.”18 The

family story, the critic notes, begins and ends with the Oedipal image of father, mother, and son, the second

family having literally or figuratively been killed off. Bentley sees the inner melodrama as a “great play of

dead or agonized fatherhood,” including the absence of the greatest father of all, God. In this vein the search

for a welcoming author can be interpreted as a metaphor for humanity’s need for the Author of our being, for

the safety and protection of absolute fatherhood. Moreover some critics employ psychoanalytic instruments

not only to explore issues of character development and plot, but also to understand the creative genesis of

Pirandello’s works in his own psychological makeup. For example, in his article “The Play as Replay,”

Rudolph Binion attributes the tragic situations of Six Characters and Henry IV to the mechanism of “traumatic

reliving” of life-shattering dramas, in an existence termed “a chronicle of psychic gashes” (149). Binion states

that a personal Pirandellian trauma is at the core of Six Characters: Antonietta Portulano’s accusations of

incest against her husband and daughter. These, Binion offers, are transformed into dramatic action in the

scenes depicting the maternally interrupted sexual encounter of the Father and Stepdaughter.

!

!10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-12-2048.jpg)

![In his depiction of the Father, Pirandello is also expressing the failure of the individual’s chosen

masks, which is concealed beneath his self-justifying rational discourse. For all his aspirations toward “a

certain moral sanity,” the Father is stripped of his masks and exposed as a bad husband, a bad parent, an

egotist, and a sensualist. Having been incapable of sustaining a satisfactory marriage, the Father becomes his

wife’s procurer when he sends her off with the Secretary. By this action he foreshadows the seventh Character,

Madama Pace, who procures the Stepdaughter for him, with intimations of an incestuous bond. It is not

coincidental that the play being rehearsed at the opening of Six Characters is Pirandello’s own The Rules of

the Game. Besides forming a comic self-referential aside, the mention and brief discussion of this earlier piece

presage themes of the new text. Like The Rules of the Game, Six Characters is also about roles. On stage,

these roles often clash: father versus child; actor versus character; husband versus wife. The Father is urgent

about his personal tragedy; he has been caught in the compromising role of the middle-aged client of the

disreputable Madama Pace and fixed in it. Madama Pace’s own “nature” is visualized in her grotesque

appearance. The corruption of her character is rendered by the monstrousness of her physique: a hideous old

harridan wearing an orange wig, red silk gown, and a rose behind her car, she is enormously fat.

!

Theoretically, dramatically, and emotionally Pirandello’s theater plays reflect the playwright’s vital

imagination and creativity. Their innovative use of the total theater, their exploration of the creative process in

action, and their invention of novel ways to express human experience make them unique in Pirandello’s

dramatic output and revolutionary within the framework of the European theater of his day. By exposing the

illusion of theater and opening it to public view, Pirandello, fulfilling his goal of capturing the instability of

life and fixing it in dramatic form, redefined the nature of the dramatic work and broke the conventions of

naturalism. In so doing, he made the audience an active, as well as reactive, participant in the construction of

drama. As the playwright declares in the introduction to Six Characters in Search of an Author, “I have set

before them [the audience], not the stage now, but my own imagination in the guise of that stage, caught in the

act of creation” (xxiii). (Understanding Luigi Pirandello By Fiora A. Bassanese)

!

DEATH OF THE AUTHOR

!

“Nature uses human imagination to lift her work of creation to even higher levels.”

!

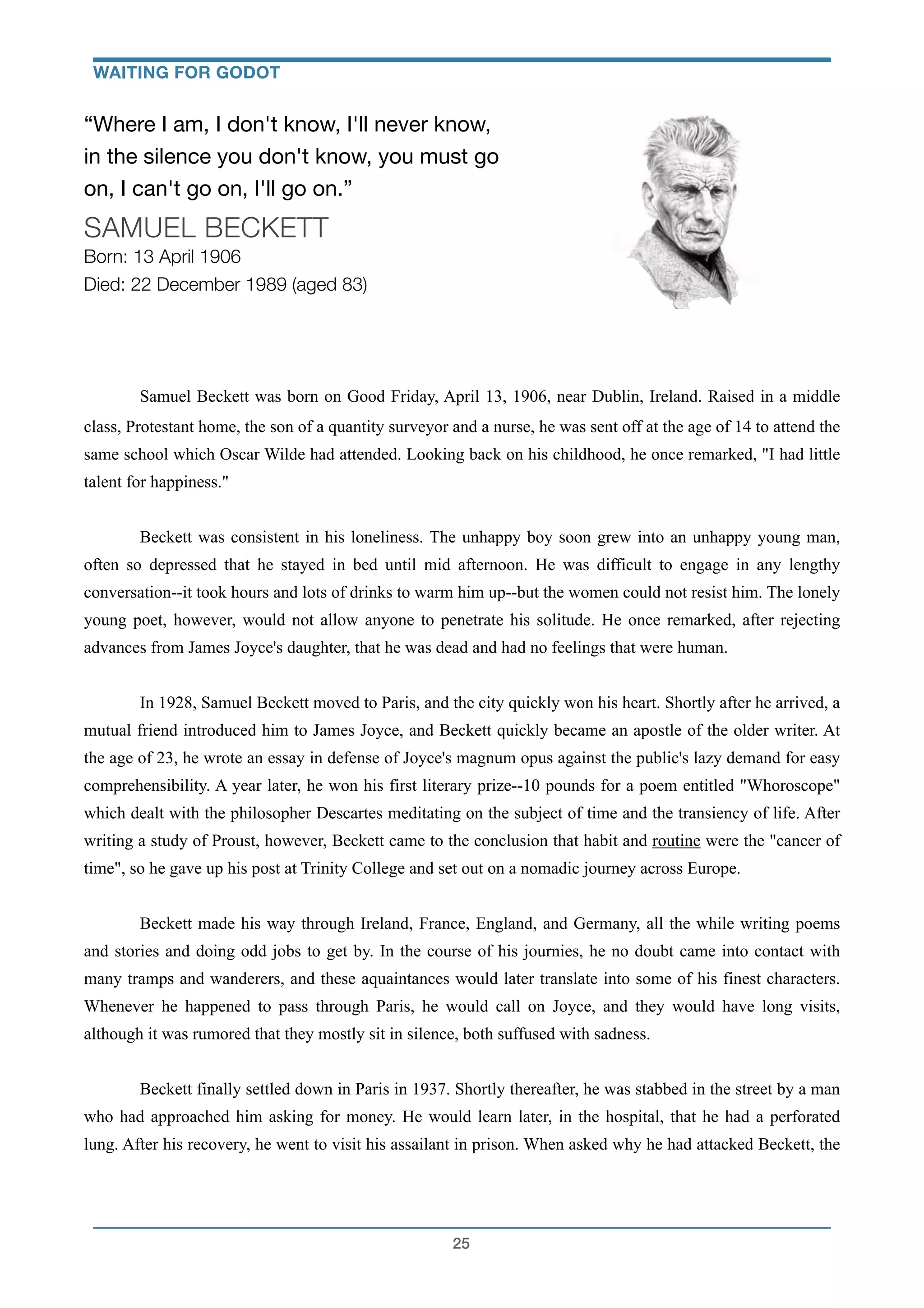

“Death of the Author” (1967) is an essay by the French literary critic

Roland Barthes that was first published in the American journal Aspen. The

essay later appeared in an anthology of his essays, Image-Music-Text (1977), a

book that also included “From Work To Text”. It argues against incorporating

the intentions and biographical context of an author in an interpretation of text;

writing and creator are unrelated.

!

!11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-13-2048.jpg)

![In his essay, Barthes criticizes the reader’s tendency to consider aspects of the author’s identity-his

political views, historical context, religion, ethnicity, psychology, or other biographical or personal attributes-

to distill meaning from his work. In this critical schematic, the experiences and biases of the author serve as

its definitive “explanation.” For Barthes, this is a tidy, convenient method of reading and is sloppy and flawed:

"To give a text an Author” and assign a single, corresponding interpretation to it “is to impose a limit on that

text.” Readers must separate a literary work from its creator in order to liberate it from interpretive tyranny (a

notion similar to Erich Auerbach’s discussion of narrative tyranny in Biblical parables), for each piece of

writing contains multiple layers and meanings. In a famous quotation, Barthes draws an analogy between text

and textiles, declaring that a “text is a tissue [or fabric] of quotations,” drawn from “innumerable centers of

culture,” rather than from one, individual experience. The essential meaning of a work depends on the

impressions of the reader, rather than the “passions” or “tastes” of the writer; “a text's unity lies not in its

origins,” or its creator, “but in its destination,” or its audience.

!

No longer the locus of creative influence, the author is merely a “scriptor” (a word Barthes uses

expressly to disrupt the traditional continuity of power between the terms “author” and “authority”). The

scriptor exists to produce but not to explain the work and “is bom simultaneously with the text, is in no way

equipped with a being preceding or exceeding the writing, [and] is not the subject with the book as predicate.”

Every work is "eternally written here and now,” with each re-reading, because the “origin” of meaning lies

exclusively in “language itself” and its impressions on the reader.

!

Barthes notes that the traditional critical approach to literature raises a thorny problem: how can we

detect precisely what the writer intended? His answer is that we cannot. He introduces this notion in the

epigraph to the essay, taken from Honore de Balzac’s story Sarrasine (a text that receives a more rigorous

close-reading treatment in his influential post-structuralist book S/Z), in which a male protagonist mistakes a

castrato for a woman and falls in love with her. When, in the passage, the character dotes over her perceived

womanliness, Barthes challenges his own readers to determine who is speaking-and about what. "Is it Balzac

the author professing ‘literary’ ideas on femininity? Is it universal wisdom? Romantic psychology?... We can

never know.” Writing, “the destruction of every voice,” defies adherence to a single interpretation or

perspective.

!

Acknowledging the presence of this idea (or variations of it) in the works of previous writers, Barthes

cites in his essay the poet Stephane Mallarme, who said that “it is language which speaks.” He also recognizes

Marcel Proust as being “concerned with the task of inexorably blurring...the relation between the writer and

his characters”; the Surrealist movement for their employment the practice of “automatic writing” to express

“what the head itself is unaware of”; and the field of linguistics as a discipline for “showing that the whole of

enunciation is an empty process.” Barthes’s articulation of the death of the author is, however, the most

radical and most drastic recognition of this severing of authority and authorship. Instead of discovering a

“single ‘theological’ meaning (the ‘message’ of the Author-God)," readers of text discover that writing, in

!12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-14-2048.jpg)

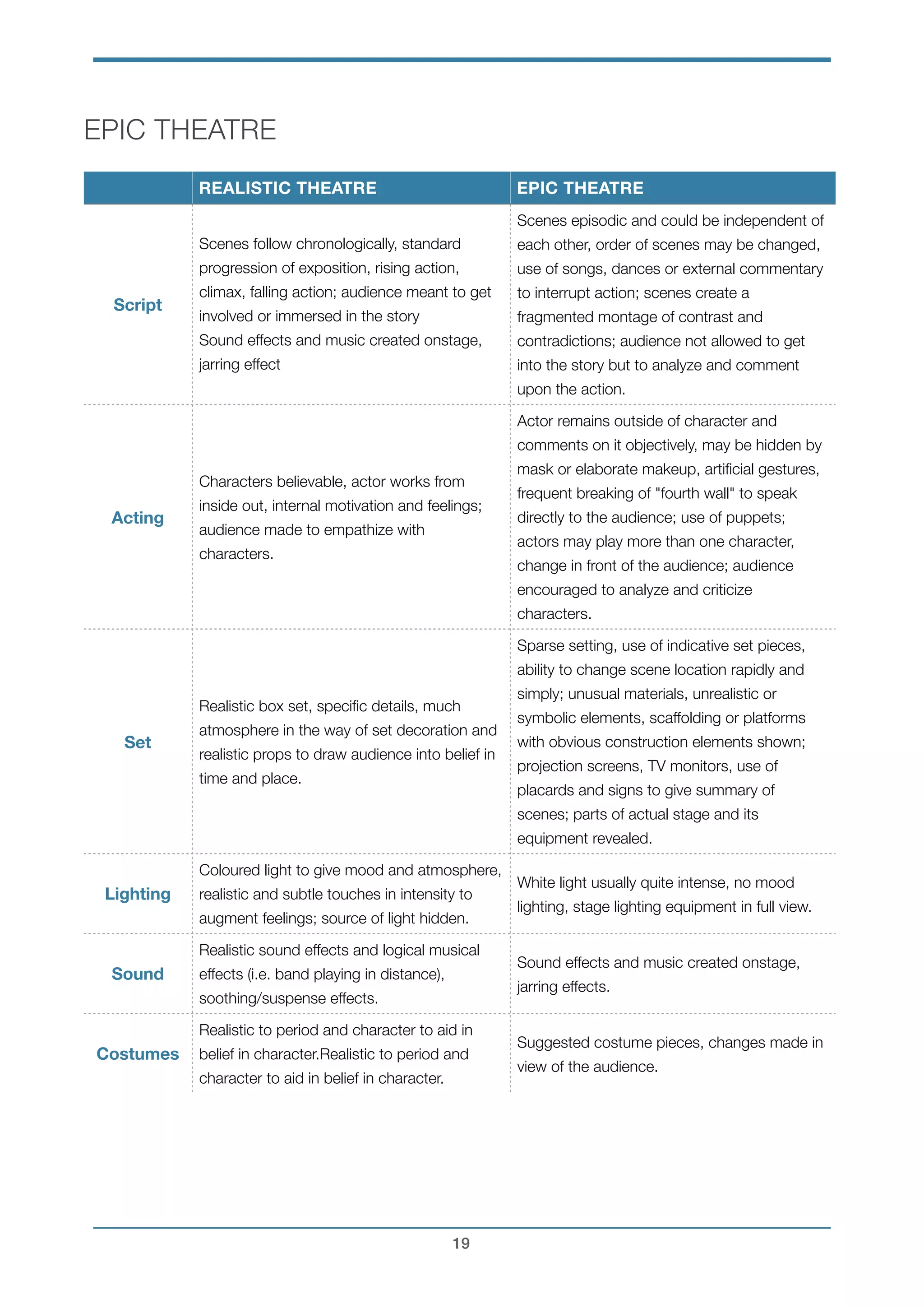

![Brecht had a strong reaction to the generally apolitical nature of the theatre around which he grew up,

particularly the realistic drama of Konstantin Stanislavski. Both Brecht and Stanislavski were reacting to the

shallow spectacle, manipulative plots and exaggerated emotions of the 19th century's melodramas. The two

theatre practitioners, however, went in opposite directions. When Brecht began working as a writer and a

director, the Second World War was a large threat, and he believed that theatre should engage more directly

with the political climate of its day. Whereas Stanislavski hoped to so immerse the audience in the world of

his plays that they too experienced what the characters experienced, Brecht took a didactic approach hoping to

jar his audience into learning his message.

!

"Epic Theatre" was Brecht's term for the form of theatre he hoped would achieve this goal. Its basic

aim was to educate its audience by forcing them to view the action of the play critically, from a detached,

"alienated", point of view, rather than allowing them to become emotionally involved. The famous "willing

suspension of disbelief", where the audience switched off its critical faculties in order to believe in the world

of the play, was the polar opposite to Brecht's epic theatre. Whereas realistic theatre or a "good movie" make

us forget we are in a theatre, Brecht reminds his audience constantly that what is before them is artificial and

presentational. Brecht in his book Brecht on Theatre says: "It is most important that one of the main features

of the ordinary theatre should be excluded from [epic theatre]: the engendering of illusion."

!

Brecht saw Stanislavski's method of absorbing the audience completely into the fiction of the play as

escapism. Brecht's social and political focus departed also from other theatre movements of the early 20th

century such as surrealism and the Theatre of Cruelty as developed in the writings and dramaturgy of Antonin

Artaud, who sought to affect audiences psychologically, physically, and irrationally. Epic theatre also differed

from Theatre of the Absurd, whose principal exponents were Beckett, Ionesco and Genet. These authors did

not set out to present a thesis or tell a story but to present images of a disintegrating world that has lost its

meaning or purpose. They place audiences in a dramatic situation in which man's fears, shames, obsessions,

and hopes are acted out in an atmosphere like a dream, carnival or altered mental state.

!

Brecht rejected the standard Aristotelian dramatic construction for a play and its adherence to the plot

pyramid - exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution - for one in which each element or scene

of the play could be considered independent of the rest, much like a music hall act which can stand on its own.

His plays would not be considered comedies or tragedies but dialectical comments on society.

!

Brecht devised an acting technique for his epic theatre which he called gestus involving physical

gestures or attitudes. The physicality shown to the audience reveals the intent or the personality of the

character. Another activity suggested by Brecht to his actors was that at an early rehearsal the actor should:

first, change the dialogue from first to third person; second, change the dialogue from present to past tense;

and third, read all stage directions aloud. In later rehearsals, the actor should keep these feelings of

!20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-22-2048.jpg)

![no longer considered to be true, there was reconsideration, particularly of philosophical, and religious ideals.

The foundations of society had shifted and artists and playwrights explored profound ideological conflict in

their responses. Post World War II society was new, the world had changed, and could never be the same

again after the millions of deaths and the dropping of the bomb.

!

Waiting for Godot, questions and confronts its contextual paradigms, incorporating both existentialism

and nihilism. There was an upheaval of the foundations of religion due to the aftermath of World War II. The

existentialist idea of waiting for God, and yet God never comes, was very controversial and confronting for

the audience of the time. When the play was first performed in 1955, audience members were recorded

walking out of the theatre because of the absurdity and confronting nature of the play. Philosophical questions

about existence are raised, discussed, and then juxtaposed with a sight gag, vaudeville humor, or the mundane,

such as the fussing over the boots and bowler hats. The satiric humor undertaken by the characters subverts

what should be tragically nihilistic, into a blackly comedic romp, enjoyable for the audience, and creating

relief from the perpetual philosophical questions. Beckett himself stated 'If I could have expressed the subject

of my work in philosophical terms, I wouldn’t have had any reason to write it.' This outlines how

philosophically important the play was at the time of its release. During to the context of the play, the

1940-50s, existentialist thinking was persuasive, a work about the individual’s quest for purpose included

current controversies about the questioning of existence and religion. Past atrocities such as the holocaust, and

the atomic attacks on Japan caused a change in people’s thinking, religion was indeed questioned and

existentialism was starting to be popularly embraced, for what kind of God could allow the horrors of war

which are still affecting the current generation? This uncertainty, cultural ruin and the physical devastation of

post World War Europe and its accompanying disappointment and angst is captured by Beckett through both

the post apocalyptic setting of the play and the issues explored through his construction of character.

!

“[Waiting for Godot] will make it easier for me and everyone else to write freely

in the theatre.”

William Saroyan

By challenging religious and philosophical paradigms through the dialogue of his characters, Beckett

questions the humanity and beliefs typical of his context. As 'nothing happens, twice', the audience is being

presented with the idea of 'nothing to be done'. Mistakes and major events are repeated by the characters

representing all of humanity. Life and time, World War grief, Cold war uncertainty and the pointlessness of

religion, is being mirrored by Waiting for Godot through Beckett's use of the repetitive structure of absurd

theatre. The philosophical, questioning dialogue of Beckett's characters captures the challenging of prevailing

paradigms and the personal ramifications of the political and philosophical shifts in thinking of the era.

(Monotony Strange, Waiting For Godot, how it mirrors cold war anxiety)

!

!27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-29-2048.jpg)

![!

Lucky

As noted above, Lucky is the obvious antithesis of Pozzo. At one point, Pozzo maintains that Lucky's

entire existence is based upon pleasing him; that is, Lucky's enslavement is his meaning, and if he is ever

freed, his life would cease to have any significance. Given Lucky's state of existence, his very name "Lucky"

is ironic, especially since Vladimir observes that even "old dogs have more dignity."

!

All of Lucky's actions seem unpredictable. In Act I, when Estragon attempts to help him, Lucky

becomes violent and kicks him on the leg. When he is later expected to dance, his movements are as

ungraceful and alien to the concept of dance as one can possibly conceive. We have seldom encountered such

ignorance; consequently, when he is expected to give a coherent speech, we are still surprised by his almost

total incoherence. Lucky seems to be more animal than human, and his very existence in the drama is a

parody of human existence. In Act II, when he arrives completely dumb, it is only a fitting extension of his

condition in Act I, where his speech was virtually incomprehensible. Now he makes no attempt to utter any

sound at all. Whatever part of man that Lucky represents, we can make the general observation that he, as

man, is reduced to leading the blind, not by intellect, but by blind instinct.

!

Pozzo and Lucky

Together they represent the antithesis of each other. Yet they are strongly and irrevocably tied together

— both physically and metaphysically. Any number of polarities could be used to apply to them. If Pozzo is

the master (and father figure), then Lucky is the slave (or child). If Pozzo is the circus ringmaster, then Lucky

is the trained or performing animal. If Pozzo is the sadist, Lucky is the masochist. Or Pozzo can be seen as the

Ego and Lucky as the Id. An inexhaustible number of polarities can be suggested. (Cliffsnotes website)

!

Godot

!

[Another] story has Beckett rejecting the advances of a prostitute on the rue Godot de Mauroy only to

have the prostitute ask if he was saving himself for Godot. Beckett’s longtime friend and English publisher

John Calder summarises Beckett’s position on the play thus: "He wanted any number of stories circulated, the

more there are, the better he likes it.” (S E Gontarski "Dealing with a Given Space”)

!

Without either accepting or rejecting the widespread view that Waiting for Godot is a religious

allegory, let us consider what problems confront a dramatist who wishes to write a play about waiting—a play

which virtually nothing is to happen and yet the audience are to be cajoled into themselves waiting to the

bittersweet end. Obviously those who wait on stage must wait for something that they and the audience

consider extremely important.

!31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-33-2048.jpg)

![When the Son of man shall come in his glory, and all the holy angels with him, then shall he sit upon

the throne of his glory: And before him shall be gathered all nations; and he shall separate them one

from another, as a shepherd divideth his sheep from the goats: And he shall set the sheep on his right

hand, but the goats on the left. Then shall the King say unto them on his right hand, Come, ye

blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. . . .

Then shall he say also unto them on the left hand, Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire,

prepared for the devil and his angels. . . . And these shall go away into everlasting punishment: but

the righteous into life eternal. (Matthew 25:31-46)

This parable is, of course, a narrative about salvation and damnation; the sheep are the saved, the goats the

damned. It is significant that the messenger who attends Vladimir and Estragon is the goatherd. Previous

ironies about the nature of the God parodied in this play are intensified by his perverse beating of the boy who

tends the sheep, not the one who tends the goats (the damned are damned and the saved get beaten). Act II

ends after the appearance of a similar messenger (apparently not the same one, but not necessarily his

shepherd brother either). This boy, in response to questions, provides the information that Godot has a white

beard, frightening Vladimir into pleas for mercy and expectations of punishment. (Biblical Allusions in

Waiting for Godot by Kristin Morrison)

!

From all this we may gather the Godot has several traits in common with the image of God as we

know it from the Old and New Testament. . . . The discrimination between goatherd [Satanic] and shepherd

[priestly—agnus dei] is reminiscent of the Son of God as the ultimate judge [judicare vivos et mortuos] . . .

while his doing nothing might be an equally cynical reflection concerning man’s forlorn state. This feature,

together with Beckett’s statement about something being believed to be " in store for us, not in store in us ,"

seems to show clearly that Beckett points to the sterility of a consciousness that expects and waits for the old

activity of God or gods.

!

Whereas Matthew (25,33) says: "And he shall seat the sheep on his right hand, but the goats on the

left" in the play it is the shepherd who is beaten and the goatherd who is favoured. What Vladimir and

Estragon expect from Godot is food and shelter, and goats are motherly, milk-providing animals. In antiquity,

even the male goats among the deities , like Pan and Dionysos, have their origin in the cult of the great mother

and the matriarchal mysteries , later to become devils.

!

Today religion altogether is based on indistinct desires in which spiritual and material needs remain

mixed. Godot is explicitly vague, merely an empty promise, corresponding to the lukewarm piety and absence

of suffering in the tramps. Waiting for him has become a habit which Beckett calls a "guarantee of dull

inviolability", an adaptation to the meaningless of life. " The periods of transition ," he continued, "that

separate consecutive adaptations . . . represent the perilous zones in the life of the individual, dangerous,

precarious, mysterious and fertile, when for a moment the boredom of living is replaced by the suffering of

being. (Reflections on Samuel Beckett's Plays by Eva Metman)

!33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-35-2048.jpg)

![Paradoxically, this persistent verbal ambiguating of the tree has the effect of asserting its stage its stage

identity, . . . Once so established, . . . the tree functions as a sign of a tree and the question of its materiality

becomes irrelevant. . . . The stage tree refers to a real tree not because it looks like one (though it may) but

because it creates the stage as a road (in a world) and the actors as characters (rather than, as metatheatrical

readings insist, as performers).

!

Thus the function of the tree goes beyond its world-creating capacity. The tree becomes one of the

principal mechanisms of the characters’ self-constitution, the sign of the area within which their existence

might ultimately make sense. It is not so much a question of their "doing" the tree: the tree "does" them. While

the theatrically absent road tends to theatricalise the characters, to unravel their characterological existence by

placing them on a "mere" stage, the tree (despite its impoverished aspect) richly bestows dramatic identity on

the tramps. In this regard, it does not recall the Christian images with which it has been associated as much as

it does the sacred post of the voodoo séance, down which the Mystères descend to earth. Here, it is not

divinity that the tree attracts like a lightning rod but fictionality: another absent world that constitutes the

actors as characters. Within the world thus created, Godot is not merely an absence but a character, however

stubbornly diegetic. His literal absence, colliding with the others’ literal presence, partakes of their

referentiality. The question of his identity, while it can never be answered, cannot be wished away either. (A

Semiotic Approach to Beckett's Play by June Schlueter and Enoch Brater)

!

In ancient Egyptian art, the Tree is depicted as bringing forth the Sun itself. This Cosmic Tree, the

living Source of radiant energy/be-ing, is the deep Background of the christian cross, the dead wood rack to

which a dying body is fastened with nails. As [Helen] Diner succinctly states: "In Christianity, the tree

becomes the torture cross of the world".

!

Thus the Tree of Life became converted into the symbol of the necrophilic S and M Society. This grim

reversal is not peculiar to Christianity. It was a theme of patriarchal myth which made christianity palatable to

an already death-loving society. Thus Odin,worshiped by the Germans, was known as "Hanging God", "the

Dangling One", and "Lord of the Gallows". [Jungian Erich] Neumann remarks that "scarcely any aspect of

their religion so facilitated the conversion of the Germans to Christianity as the apparent similarity of their

hanged god to the crucified Christ." In the cheerful German version, the tree of life, cross and gallows tree are

all forms of the "maternal" tree.

!

The christian culmination of the Tree of Life is analysed by Neumann in the following manner:

!

Christ, hanging from the tree of death, is the fruit of suffering and hence the pledge of the promised

land , the beatitude to come; and at the same time He is the tree of life as the god of the grape. Like

Dionysis, he is endendros, the life at work in the tree, and fulfills the mysterious twofold and

contradictory nature of the tree.

!35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-37-2048.jpg)

![We are told that the Cross is a bed. It is not only Christ's "marriage bed" , but also it is "crib, cradle and nest".

It is the "bed of birth and . . . it is the deathbed”. (Mary Daly, Gyn/Ecology)

[quoting Beckett]:

!

If life and death did not both present themselves to us, there would be no inscrutability. If there were

only darkness, all would be clear. It is because there is not only darkness but also light that our

situation becomes inexplicable. Take Augustine’s doctrine of grace given and grace withheld: have

you pondered the dramatic qualities of this theology? Two thieves are crucified with Christ, one

saved and the other damned. How can we make sense of this division? In classical drama, such

problems do not arise. The destiny of Racine’s Phedre is sealed from the beginning: she will proceed

into the dark. As she goes, she herself will be illuminated. At the beginning of the play she has

partial illumination and at the end she has complete illumination, but there has been no question but

that she moves toward the dark. That is the play. Within this notion clarity is possible, but for us who

are neither Greek nor Jansenist there is not such clarity. The question would also be removed if we

believed in the contrary—total salvation. But where we have both dark and light we have also the

inexplicable. The key word in my plays is "perhaps".

I would gloss his commentary as follows: Vladimir and Estragon stand for the "we", two moderns

befogged in the inexplicable greyness of "perhaps". Pozzo is Phedre: a relic, an anachronism, an erstwhile

truth—but even so the logical historical argument to the contrary. That is, if one were posing a contrast that

would illustrate how far we have come from an accountable universe, it might be the dark world of tragedy

which has, at least, the comfort of being designed and instructive. Pozzo’s destiny, like Phedre’s is sealed from

the beginning; he proceeds into the dark, and though we do not see the scene, we presume that "as he goes" he

is illuminated. I am assuming that what Beckett means by "illumination" is the process by which the tragic

hero is made aware . . . of what the journey into the dark means. In other words, tragedy is "a complex act of

clarification". In Pozzo this act is condensed into one speech in which he stands outside time in a brief space

of temporal integration. What he says is that all crises, from the coming hither to the going hence, take place

in the same second. The light gleams an instant, then it is night once more.

!

Actually, Pozzo might have answered Vladimir’s question (" Since when ?") even more

philosophically by quoting one of Beckett’s favourite secular thinkers: "Our own past," Schopenhauer says,

"even the most recent, even the previous day, is only an empty dream of the imagination. . . . What was?

What is? . . . Future and past are only in the concept. . . . No man has lived in the past, and none will ever live

in the future; the present alone is the form of all life. . . . “ (Bert O States The Shape of Paradox: An Essay on

Waiting for Godot)

(http://www.samuel-beckett.net/Penelope/Godot.html)

!

!

!

!

!36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-38-2048.jpg)

![!

Today, the functions of the theater have been largely replaced by cinema, although theater

continues to attract a fairly large following. Musical theater has also emerged as a popular entertainment art

form. Already in the 1920s musicals were transformed from a loosely connected series of songs, dances, and

comic sketches to a story, sometimes serious, told through dialogue, song, and dance. The form was extended

in the 1940s by the team of Richard Rodgers (1902-1979) and Oscar Hammerstein II (1895-1960) and in the

1980s by Andrew Lloyd Webber (1948- ) with such extravagantly popular works as Cats (1982) and Phantom

of the Opera (1988).

!

It should be mentioned, as a final word on theater, that theatrical practices in Asia—in India.

China. Japan, and Southeast Asia—have started to attract great interest from the West. The central idea in

Asian performance art is a blend of literature, dance, music, and spectacle. The theater is largely participatory

—the audience does not actually take part in the performance, but participation unfolds like a shared

experience. The performances are often long, and the spectators come and go, eating, talking, and watching

only their favorite moments. The West discovered Asian theater in the late nineteenth century, a discovery that

has gradually influenced many contemporary forms of acting, writing, and staging.

!

TIME

!

“the play doesn’t tell a story, it’s an exploration if a static situation.”

Martin Esslin

!

Apart from young people, there is one other social group whose lack of ingrained theatrical

expectations left them wide open to the impact of a Beckett play: long-term convicts. . . . [Consider] the

reaction of fourteen hundred convicts in San Quentin penitentiary when they saw Godot in 1957. They wrote a

series of articles in their prison newspaper showing how the play had expressed their own situation by virtue

of the fact that its author expected each spectator to draw his own conclusions. . . . The following year some

prisoners put on their own production of Waiting for Godot, and from that a Drama Society flourished in the

prison. It was so successful that in 1970 they had written a play and had been paroled in order to tour the

United States with it.

!

A common factor in all of Beckett’s dramas is that the figures portrayed are all imprisoned. Some can move

away for a short time, in a restricted area, but they are all quite incapable of extended mobility; which forces

our attention upon the extent to which we normally depend on mobility—both in life and in literature.

Mobility offers the chance of escape from an undesirable situation , and the possibility of communication with

!47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-49-2048.jpg)

![Structurally as well as thematically, Godot is an "incomplete" play; and its openness is not at the end

but in many places throughout: it is a play of gaps and pauses, of broken-off dialogue, of speech and action

turning into time-avoiding games and routines. . . . Waiting for Godot is designed off-balance. It is the very

opposite of Oedipus. In Godot we do not have the meshed ironies of experience, but that special anxiety

associated with question marks preceded and followed by nothing.

!

[When Vladimir says to the boy " tell him you saw me "] the "us" of the first act is the "me" of the

second. Habits break old friends are abandoned, Gogo—for the moment—is cast into the pit. When Gogo

awakens, Didi is standing with his head bowed. Didi does not tell his friend of his conversation with the Boy

nor of his insight or sadness. Gogo asks, "What’s wrong with you," and Didi answers, "Nothing." Didi tells

Estragon that they must return the following evening to keep their appointment once again. But for him the

routine is meaningless: Godot will not come. There is something more than irony in his reply to Gogo’s

question, "And if we dropped him?" "He’d punish us," Didi says. But the punishment is already apparent to

Didi: the pointless execution of orders without hope of fulfillment. Never coming; for Didi, Godot has

come . . . and gone.

!

In the first act, Gogo/Didi suspect that Pozzo may be Godot. Discovering that he is not, they are

curious about him and Lucky. They circle around their new acquaintances, listen to Pozzo’s speeches, taunt

Lucky, and so on. Partly afraid, somewhat uncertainly, they integrate Pozzo/Lucky into their world of waiting:

they make out of the visitors a way of passing time. And they exploit the persons of Pozzo/Lucky, taking food

and playing games. ( In the Free Southern Theatre production, Gogo and Didi pick-pocket Pozzo, stealing his

watch, pipe and atomiser—no doubt to hock them for necessary food. This interpretation has advantages: it

grounds the play in an acceptable reality; it establishes a first act relationship of doubt exploitation‚ Pozzo

uses them as audience and they use him as income. ) In the second act this exploitation process is even clearer.

. . . Gogo/Didi try to detain Pozzo/Lucky as long as possible. They play rather cruel games with them,

postponing assistance. It would be intolerable to Gogo/Didi for this "diversion" to pass quickly, just as it is

intolerable for an audience to watch it go on so long. . . . When they are gone, Estragon goes to sleep.

Vladimir shakes him awake. " I was lonely ." And speaking of Pozzo/Lucky, "That passed the time." For

them, perhaps; but for the audience? It is an ironic scene—the entire cast sprawled on the floor, hard to see,

not much action. It makes an audience aware that the time is not passing fast enough.

!

If waiting is the play’s action, Time is its subject. Godot is not Time, but he is associated with it—the

one who makes but does not keep appointments. (An impish thought occurs: Perhaps Godot passes time with

Gogo/Didi just as they pass it with him. Within this scheme, Godot has nothing to do [as the Boy tells Didi in

Act Two] and uses the whole play as a diversion in his day. Thus the "big game" is a strict analogy of the

many "small games" that make the play.) The basic rhythm of the play is habit interrupted by memory,

memory obliterated by games. Why do Gogo/Didi play? In order to deaden their sense of waiting. Waiting is a

"waiting for" and it is precisely this that they wish to forget. One may say that "waiting" is the larger connect

!52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-54-2048.jpg)

![realize he has been dreaming, and must wake up and face the world as it is, that Godot’s messenger arrives,

rekindles his hopes, and plunges him back into the passivity of illusion.

!

For a brief moment, Vladimir is aware of the full horror of the human condition: ‘The air is full of our

cries…But habit is a great deadener.’ He looks at Estragon, who is asleep, and reflects, ‘At me too someone is

looking, of me too someone is saying, he is sleeping, he knows nothing, let him sleep on. . .. I can’t go on!’a

The routine of waiting for Godot stands for habit, which prevents us from reaching the painful but fruitful

awareness of the full reality of being.

!

Again we find Beckett’s own commentary on this aspect of Waiting for Godot in his essay on Proust:

‘ Habit is the ballast that chains the dog to his vomit. Breathing is habit. Life is habit. Or rather life is a

succession of habits, since the individual is a succession of individuals Habit then is the generic term for the

countless treaties concluded between the countless subjects that constitute the individual and their countless

correlative objects. The periods of transition that separate consecutive adaptations ... represent the perilous

zones in the life of the individual, dangerous, precarious, painful, mysterious, and fertile, when for a moment

the boredom of living is replaced by the suffering of being.’ ‘The suffering of being: that is the free play of

every faculty. Because the pernicious devotion of habit paralyses our attention, drugs those handmaidens of

perception whose cooperation is not absolutely essential.

!

Vladimir’s and Estragon’s pastimes are, as they repeatedly indicate, designed to stop them from

thinking. ‘We’re in no danger of thinking any more.... Thinking is not the worst.... What is terrible is to have

thought.

Vladimir and Estragon talk incessandy. Why? They hint at it in what is probably the most lyrical, the

most perfectly phrased passage of the play:

Vladimir: You are right, we’re inexhaustible.

estragon: It’s so we won’t think.

vladimir: We have that excuse.

estragon: It’s so we won't hear.

vladimir: We have our reasons.

estragon: All the dead voices.

vladimir: They make a noise like wing.

estragon: Like leaves.

vladimir: Like sand.

estragon: Like leaves.*

[Silence.]

vladimir: They all speak together.

estragon: Each one to itself.

[Silence.]

vladimir: Rather they whisper.

estragon: They rusde.

vladimir: They murmur

estragon: They rusde.

[Silence.]

vladimir: What do they say?

estragon: They talk about their lives.

!56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-58-2048.jpg)

![vladimir: To have lived is not enough for them.

estragon: They have to talk about it.

vladimir: To be dead is not enough for them.

estragon: It is not sufficient.

[Silence.]

Vladimir: They make a noise like feathers.

estragon: Like leaves.

vladimir: Like ashes.

estragon: Like leaves.

[Long silence.]

!

This passage, in which the cross-talk of Irish music-ha comedians is miraculously transmuted into

poetry, contains th key to much of Beckett’s work. Surely these rustling, murmui ing voices of the past are the

voices we hear in the three novc of his trilogy; they are the voices that explore the mysteries c being and the

self to the limits of anguish and suffering Vladimir and Estragon are trying to escape hearing them. Th long

silence that follows their evocation is broken by Vladimi 'in anguish with the cry ‘Say anything at all!* after

which th two relapse into their wait for Godot.

!

The hope of salvation may be merely an evasion of th suffering and anguish that spring from facing

the reality of th human condition. There is here a truly astonishing paralh between the Existentialist

philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre an the creative intuition of Beckett, who has never consciousl expressed

Existentialist views. If, for Beckett as for Sartre, ma has the duty of facing the human condition as a rccognitio

that at the root of our being there is nothingness, liberty, an the need of constantly creating ourselves in a

succession c choices, then Godot might well become an image of whj Sartre calls ‘bad faith’ - ‘The first act of

bad faith consists i evading what one cannot evade, in evading what one is.

!

STRUCTURE OF THE PLAY

(REPETITIVENESS,

CIRCULAR DEVELOPMENT)

!

!

Even though the drama is divided into two

acts, there are other natural divisions. For the sake

of discussion, the following, rather obvious, scene

divisions will be referred to:

!

ACT I:

(1) Vladimir and Estragon Alone

(2) Arrival of Pozzo and Lucky: Lucky's Speech

!57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dramafile2-140725183425-phpapp02/75/Drama-File-59-2048.jpg)