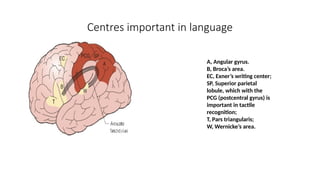

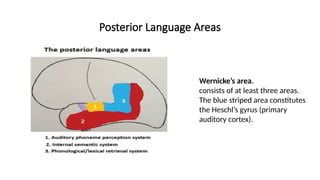

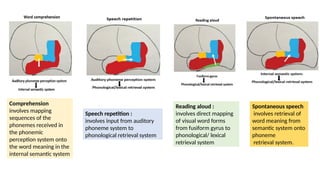

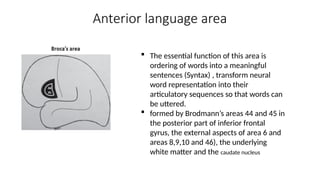

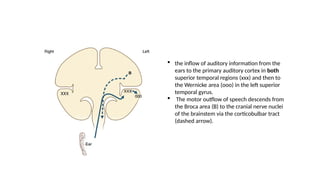

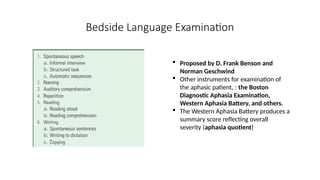

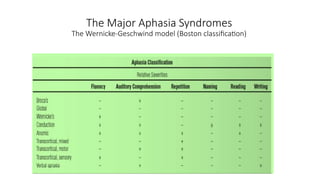

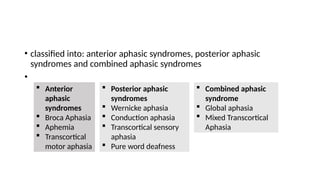

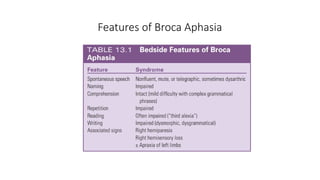

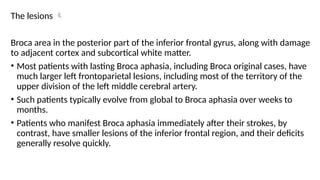

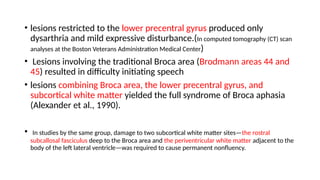

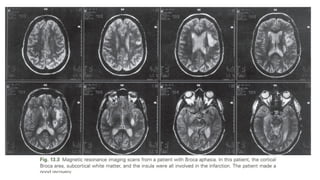

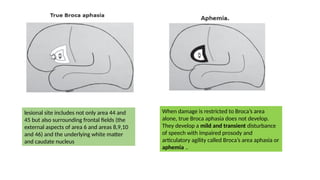

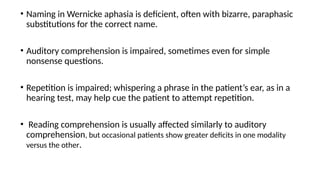

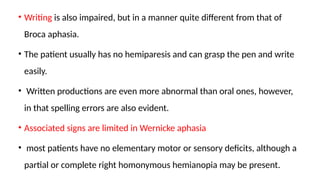

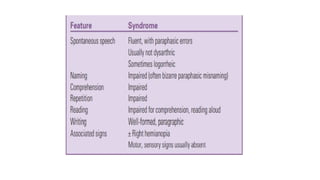

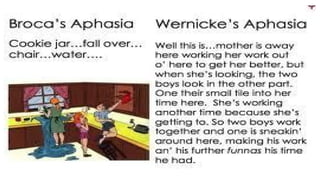

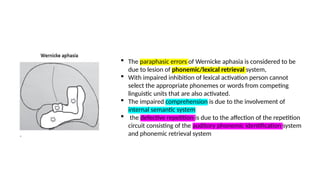

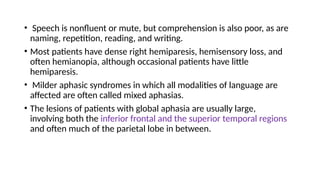

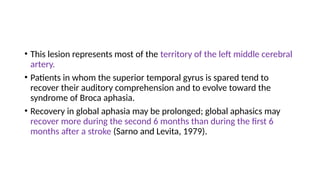

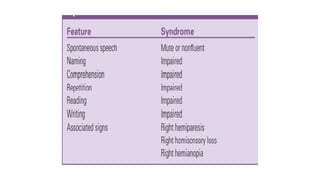

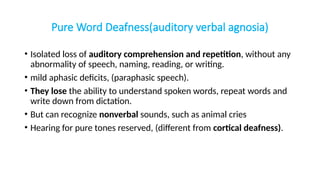

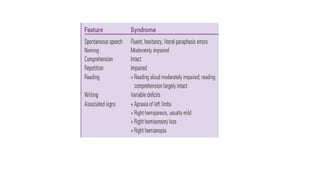

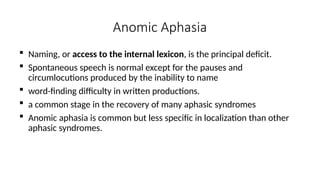

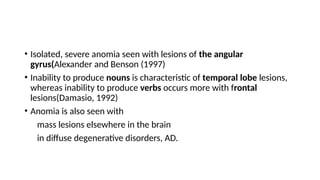

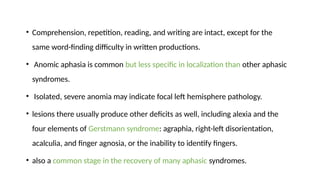

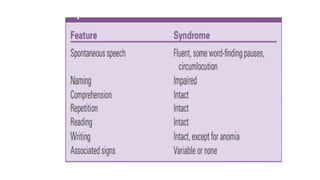

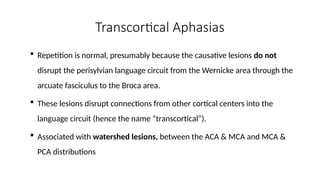

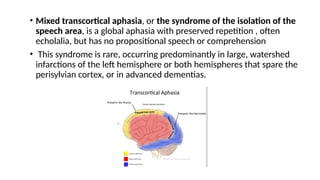

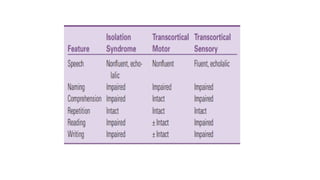

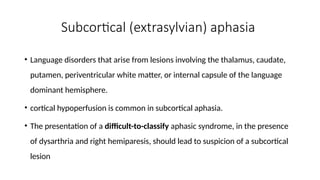

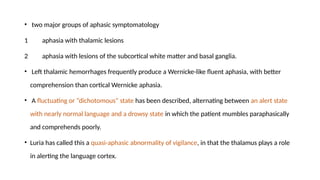

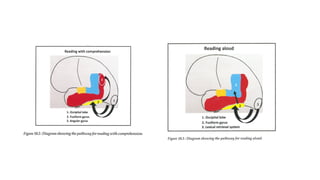

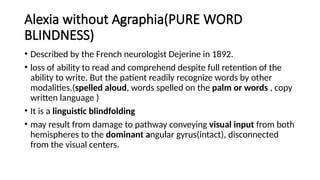

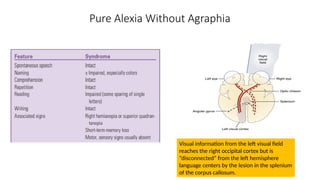

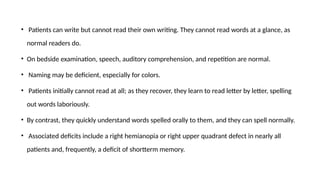

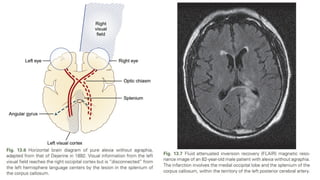

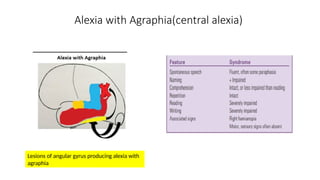

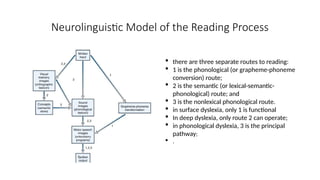

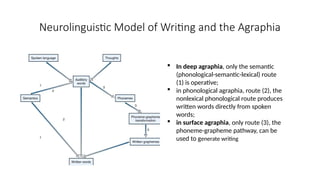

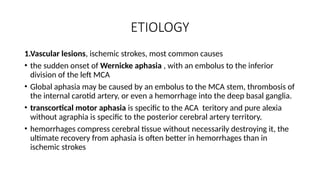

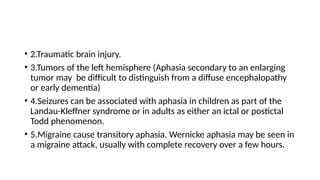

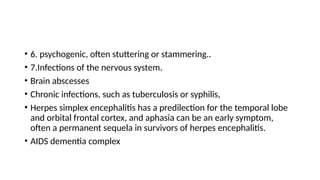

The document discusses the complexities of language and aphasia, including its neuroanatomical basis, types of aphasia, and methods for assessing language impairment. It highlights the distinction between aphasia and related disorders, and elaborates on the symptoms and recovery associated with different aphasia syndromes like Broca's and Wernicke's aphasia. Key components involved in language processing, such as speech production, comprehension, and writing are also outlined, along with strategies for patient assessment and diagnosis.