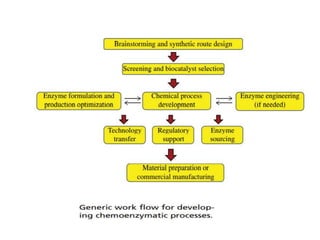

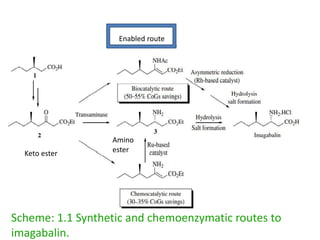

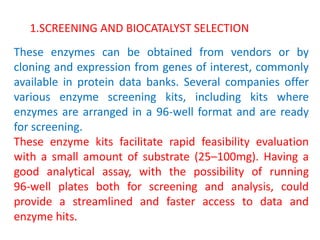

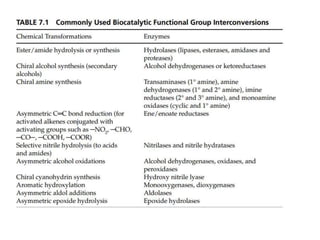

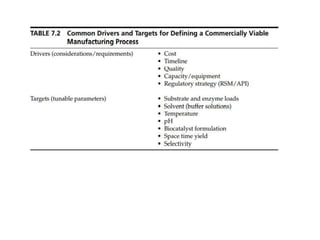

This document discusses the development of chemoenzymatic processes. It notes that while biocatalysis has been used for thousands of years, it has only emerged as a powerful tool in organic synthesis in the last 15 years. Factors driving this growth include genome sequencing, enzyme engineering, fermentation technology advances, and successful manufacturing-scale application. The document outlines key steps in integrating biocatalysis into synthesis routes including screening, selection, process development, reaction engineering, product isolation, and scale up considerations. It emphasizes the importance of enzyme activity, stability and overcoming inhibition to achieve high productivity.