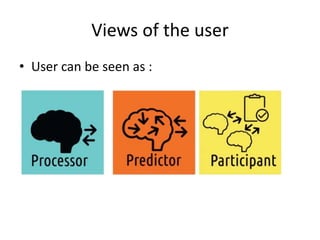

The document discusses different views of the user in user-centered design:

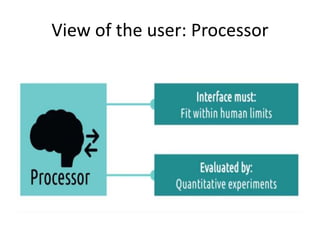

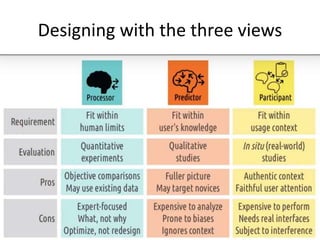

- The processor view sees the user as processing inputs and outputs like a computer. Interfaces are evaluated quantitatively based on tasks.

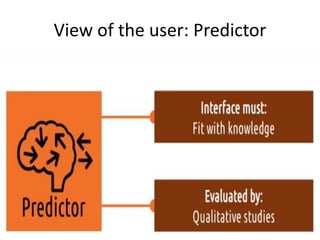

- The predictor view focuses on the user's knowledge, expectations, and thought processes to predict outcomes. Interfaces are evaluated qualitatively based on cognitive studies.

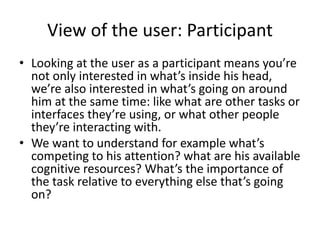

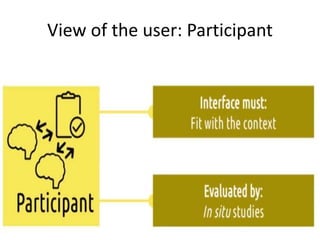

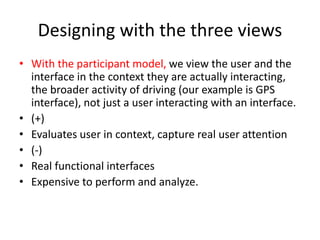

- The participant view considers the user's full context including other tasks and people. Interfaces must fit the context and are evaluated through in-situ studies in authentic environments.

Understanding these views helps design interfaces that are useful, usable, and fit the user's needs based on their role as a processor, predictor, or participant.