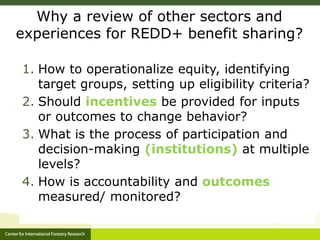

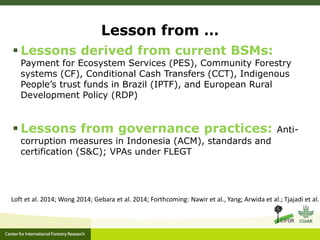

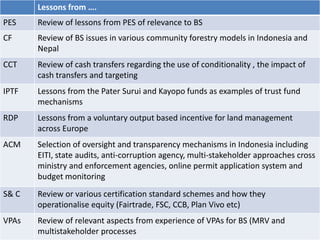

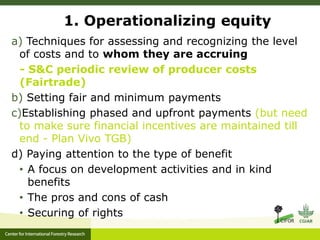

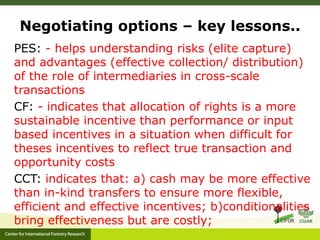

The document discusses the design and development of REDD+ benefit-sharing mechanisms, emphasizing the need for effective, efficient, and equitable outcomes in policy implementation. It reviews existing systems and provides insights from various governance practices and mechanisms, such as payment for ecosystem services and community forestry models, aiming to improve the allocation of benefits derived from REDD+ initiatives. Key considerations include the operationalization of equity, the efficiency of benefits distribution, and fostering accountability through monitoring and evaluation processes.