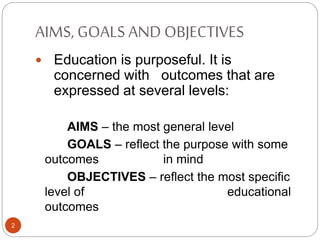

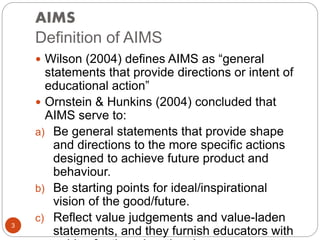

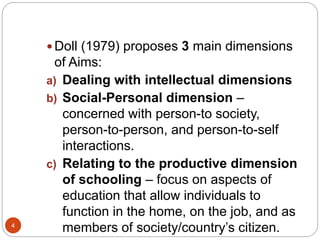

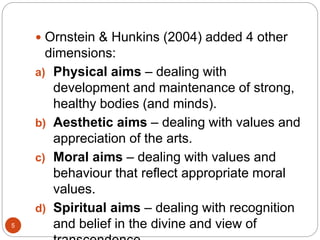

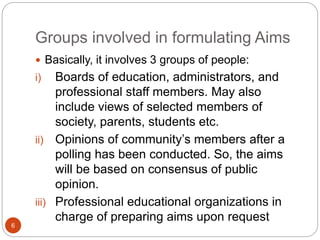

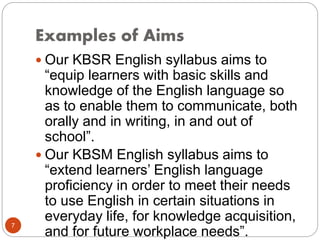

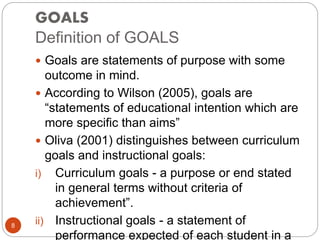

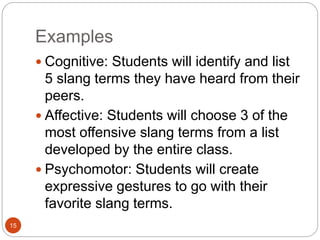

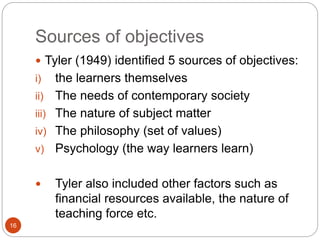

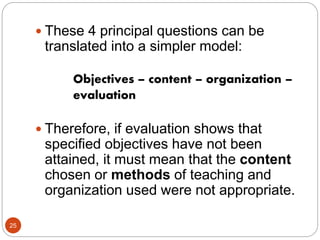

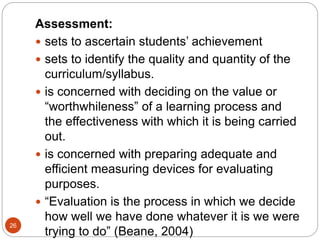

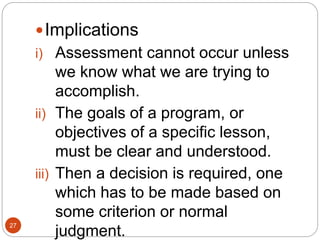

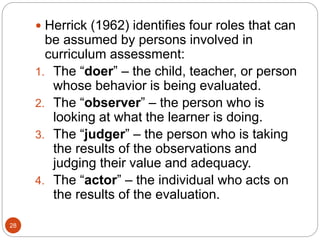

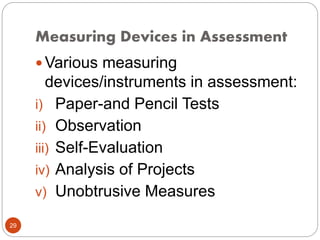

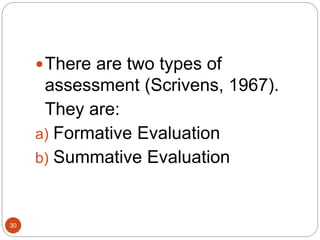

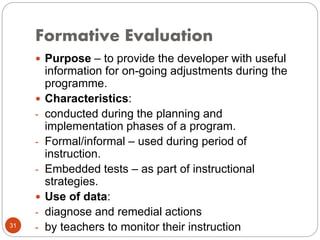

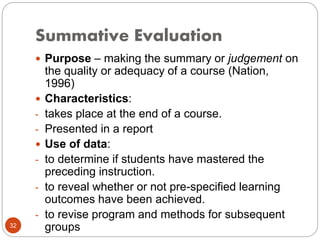

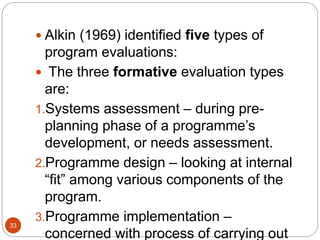

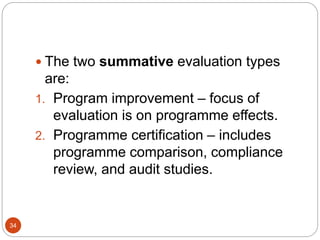

This document discusses the basic components involved in developing a curriculum, including aims, goals, objectives, content, experiences, and assessment. It defines each component and provides examples. Aims are the most general statements, goals are more specific intended outcomes, and objectives are very specific statements of expected learning. Content must account for learner needs and environment. Experiences encompass both in-school and out-of-school activities. Assessment involves evaluating if objectives are achieved and can be formative or summative in nature.