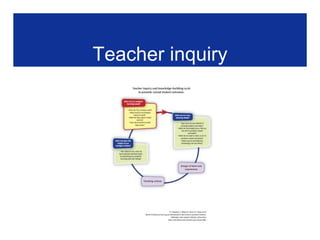

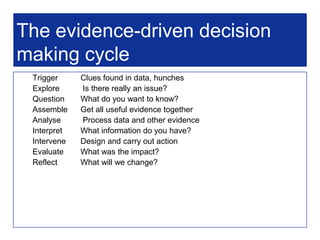

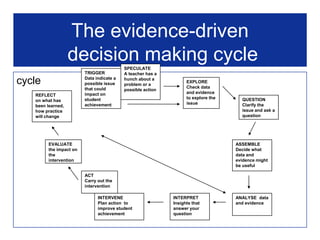

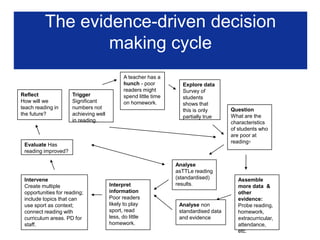

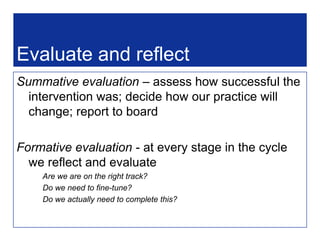

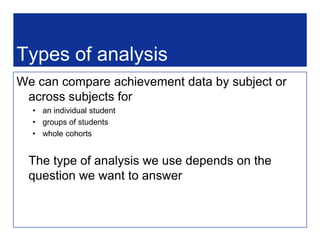

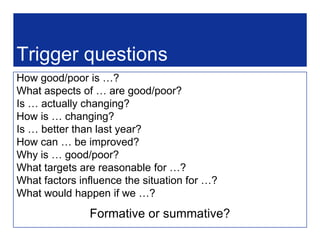

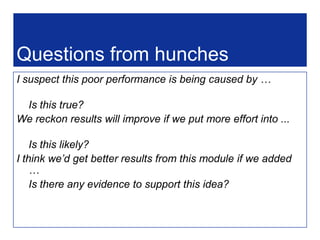

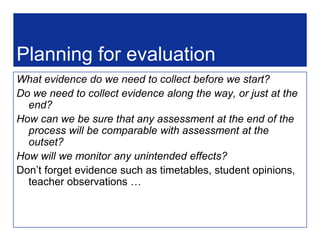

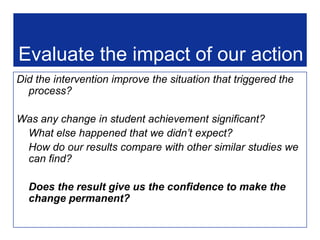

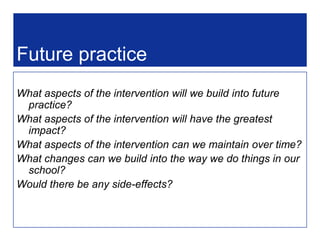

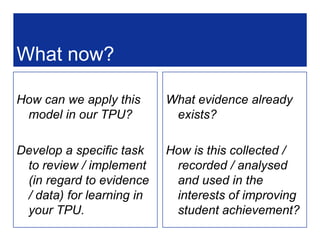

This document discusses using data and evidence to make decisions to improve teaching and learning in Teen Parent Units. It considers what data is collected, why, and how it is used. Evidence-driven decision making requires analyzing data to understand patterns and insights that can inform changes to improve student achievement. The document outlines a cycle for evidence-based inquiry including speculating about issues, exploring the evidence, questioning, assembling data, analyzing, intervening, evaluating the impact of changes, and reflecting on lessons learned. Teachers are encouraged to use this process to set goals for improving their practice using an evidence-based approach.