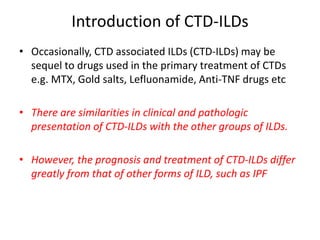

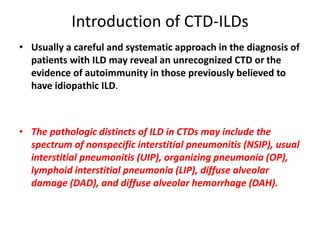

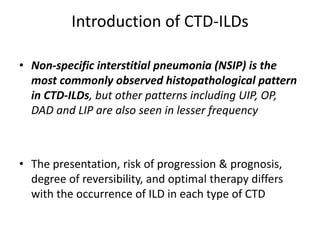

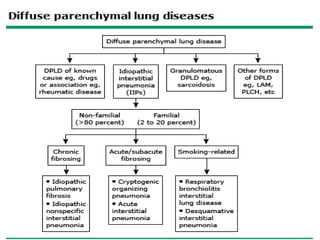

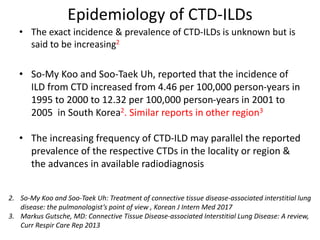

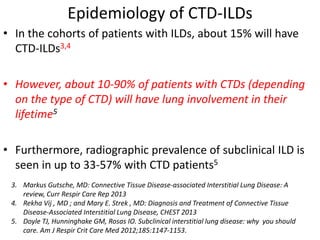

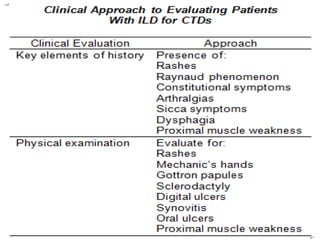

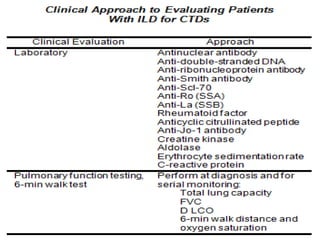

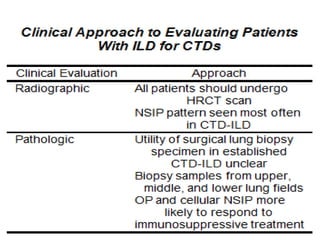

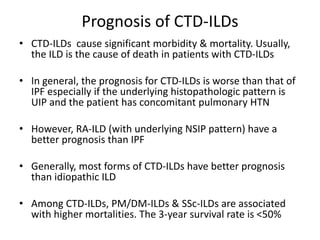

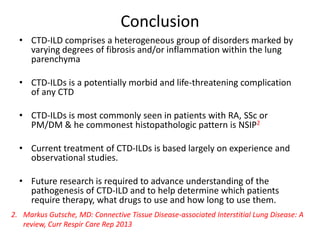

This document provides an overview of connective tissue disease (CTD)-associated interstitial lung disease (ILD). Some key points:

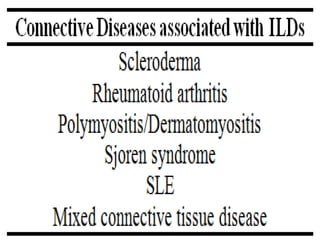

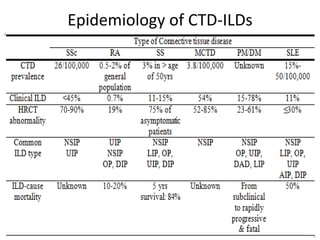

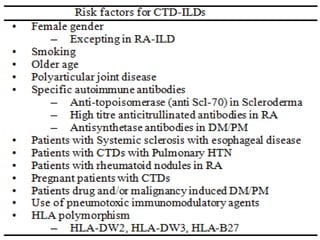

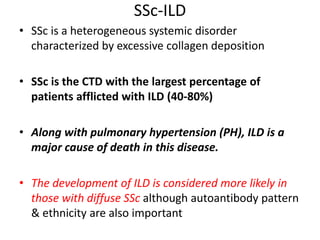

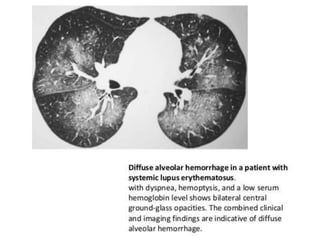

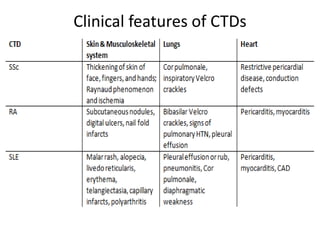

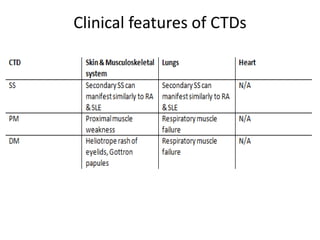

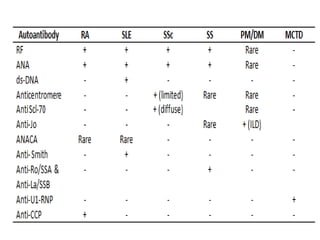

- ILD is a common pulmonary complication in patients with CTDs like systemic sclerosis (SSc), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It can occur concurrently with or after diagnosis of the CTD.

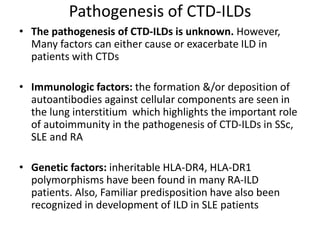

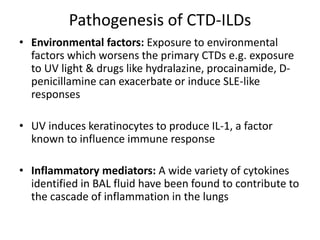

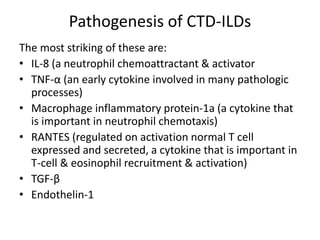

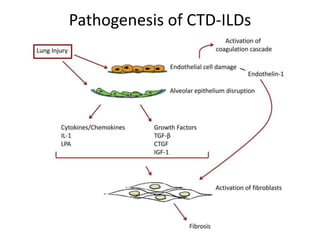

- The pathogenesis involves autoimmune mechanisms, genetic factors, environmental exposures, and inflammatory cytokines that cause lung inflammation and fibrosis.

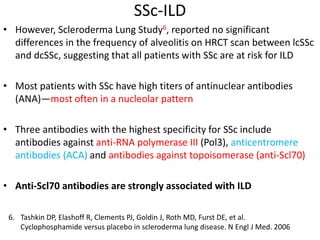

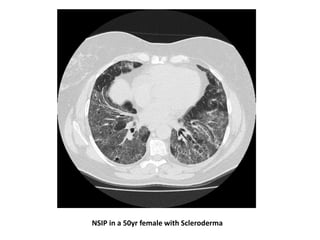

- SSc has the highest rate of ILD of all CTDs, affecting 40-80% of patients. Antibodies to topoisomerase I are associated with increased