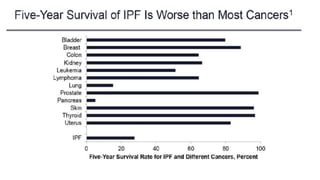

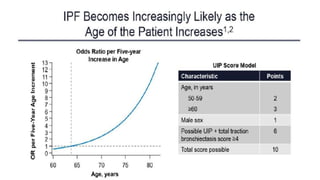

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a group of disorders causing scarring of the lungs. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is the most common ILD, accounting for around half of cases. It generally affects older adults and smokers and causes shortness of breath, cough, and lung function decline. Diagnosis involves imaging, pulmonary function tests, and biopsy. Approved treatments are pirfenidone and nintedanib, which can slow disease progression, but prognosis remains poor with median survival of 3-4 years. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is another ILD that may be idiopathic or associated with connective tissue diseases.

![• In Europe alone, approximately 40,000 new cases are diagnosed each

year. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a clinically heterogeneous

disease but its

• prognosis is overall poor, with a median survival of 3–4 years [6].

Taking all of the above into account, IPF is also an expensive disease,

with direct treatment costs of around 25,000 USD/person-year, which

is a higher cost in comparison to breast cancer and many other

serious conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/interstitiallungdisease-191030121926/85/Interstitial-lung-disease-11-320.jpg)

![• Innate immunity has been proposed to have a role in the

development and progression of IPF, mainly through the activation of

Toll-like receptor (TLR)-9 [59, 60]. TLR-3, amongst other properties,

regulates the recognition of viral pathogen-associated molecular

patterns.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/interstitiallungdisease-191030121926/85/Interstitial-lung-disease-34-320.jpg)

![• ALLAIX et al. [69] compared the clinical presentation, the oesophageal

function and the reflux profile in 80 patients with GORD to 22

patients with GORD and IPF. Results showed that GORD is often

asymptomatic in IPF patients, with heartburn present in ,60% of

patients with GORD and IPF.

• IPF patients had significantly higher oesophageal acid exposure

(9.25% versus 3.3% versus 0.7%) and proximal reflux events (median

51 versus 20 versus nine) compared to non-IPF patients and healthy

volunteers, respectively.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/interstitiallungdisease-191030121926/85/Interstitial-lung-disease-45-320.jpg)

![• It has been shown that IPF patients are more likely than controls to

have venous thromboembolism [74], and both epidemiological and

laboratory studies suggest that activation of the coagulation cascade

within the lung may be involved in the pathogenesis of IPF.

• BARGAGLI et al. [75] showed procoagulant status to correlate with IPF

and acute exacerbation of IPF compared to both NSIP and healthy

controls.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/interstitiallungdisease-191030121926/85/Interstitial-lung-disease-47-320.jpg)

![• NAVARATNAM et al. [76] investigated the presence of a pro-

thrombotic state in a large cohort of patients. They recruited 211

incident cases of IPF and 256 age- and sex-matched general

population controls and reported that IPF cases were more than four

times more likely than controls to have a pro-thrombotic state (OR

4.78 (95% CI 2.93–7.80); p,0.0001).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/interstitiallungdisease-191030121926/85/Interstitial-lung-disease-48-320.jpg)