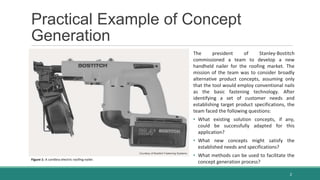

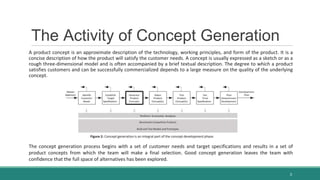

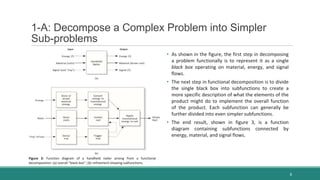

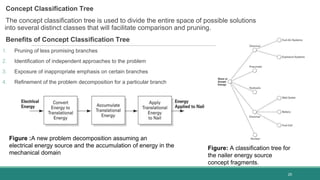

The document outlines a structured approach for concept generation in product development, utilizing a practical example of a new handheld nailer for the roofing market. It emphasizes the importance of exploring customer needs, decomposing complex problems into simpler sub-problems, and employing both external and internal searches for solutions. Key methodologies such as brainstorming, classification trees, and concept combination tables are highlighted to enhance creativity and systematically navigate the solution space.