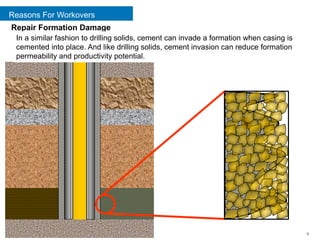

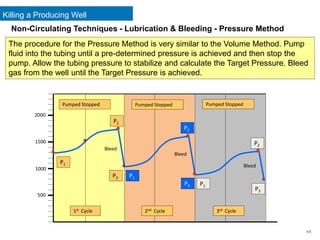

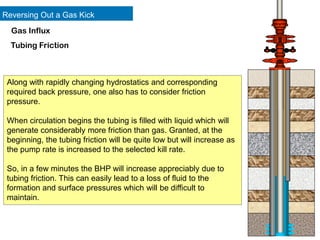

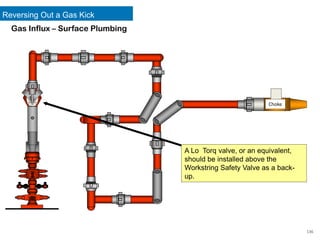

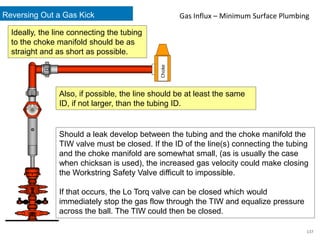

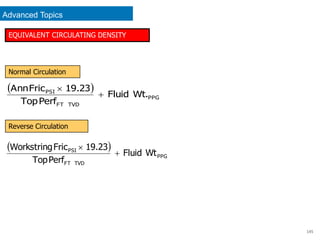

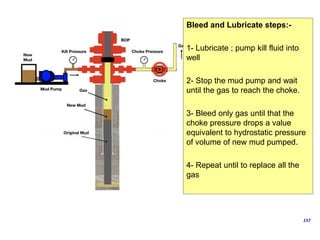

The document outlines the various reasons and techniques for workovers in oil and gas wells, including repairing mechanical and formation damage, reservoir stimulation, and completing previously non-produced reservoirs. It provides detailed descriptions of completion types, such as open hole, gas lift, and electrical submersible pumps, along with the differences between workovers and drilling. Key aspects covered also include well control techniques, managing water and gas intrusion, and the installation of velocity strings and replacement of tubing.