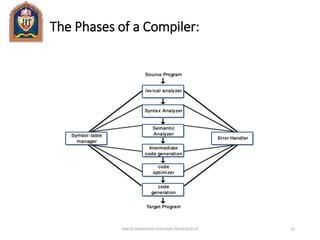

The document discusses the various phases of a compiler:

1. Lexical analysis groups characters into tokens like identifiers and operators.

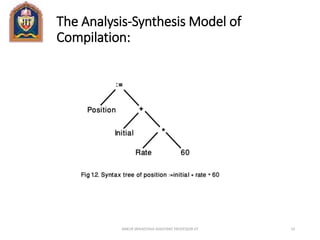

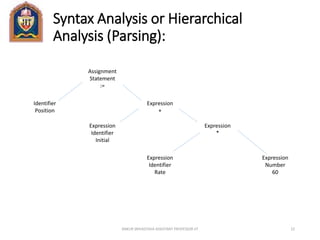

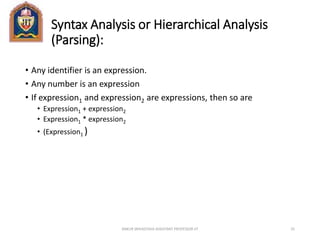

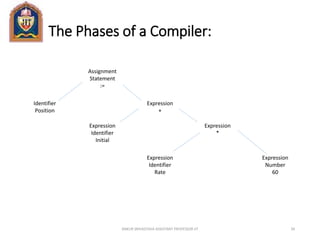

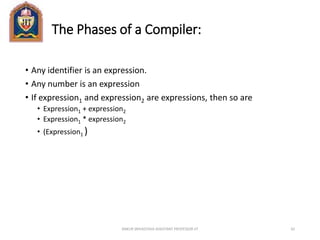

2. Syntax analysis parses tokens into a parse tree representing the program's grammatical structure.

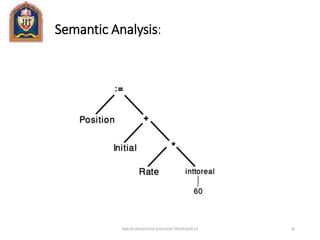

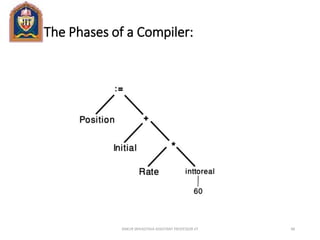

3. Semantic analysis checks for semantic errors and collects type information by analyzing the parse tree.