This research thesis by Alex Liberzon focuses on the characterization of coherent structures in turbulent flow, contributing to the understanding of turbulence through comprehensive literature reviews and experimental techniques. It includes detailed mathematical backgrounds and analysis approaches, along with results from various experimental setups like stereoscopic PIV systems. The findings aim to provide insights into coherent structures in turbulent flows and suggest areas for further research.

![LIST OF FIGURES ix

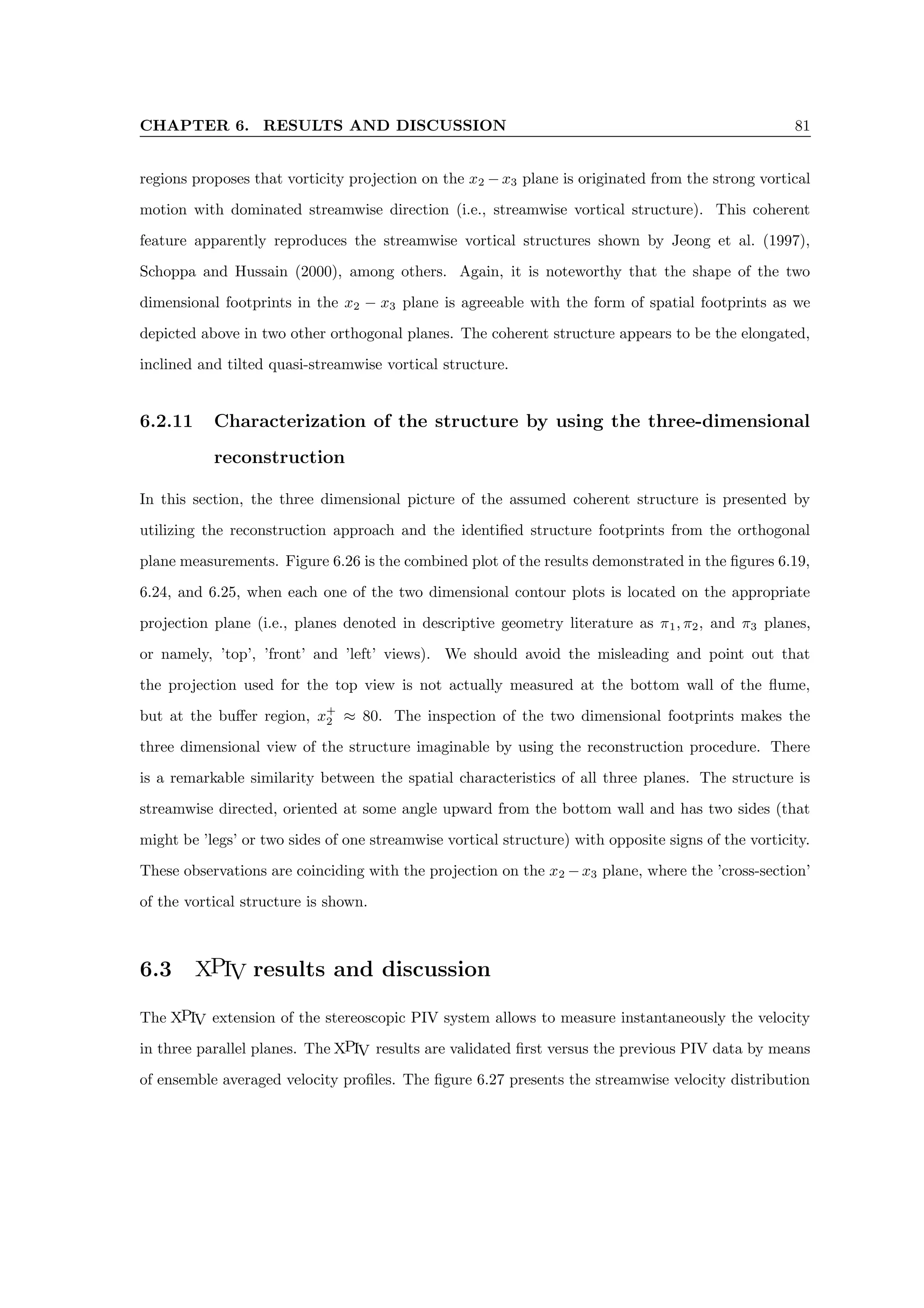

6.23 Instantaneous field of the streamwise velocity fluctuations (red and blue line contours)

over the field of the ∂(u1u3)

∂x3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

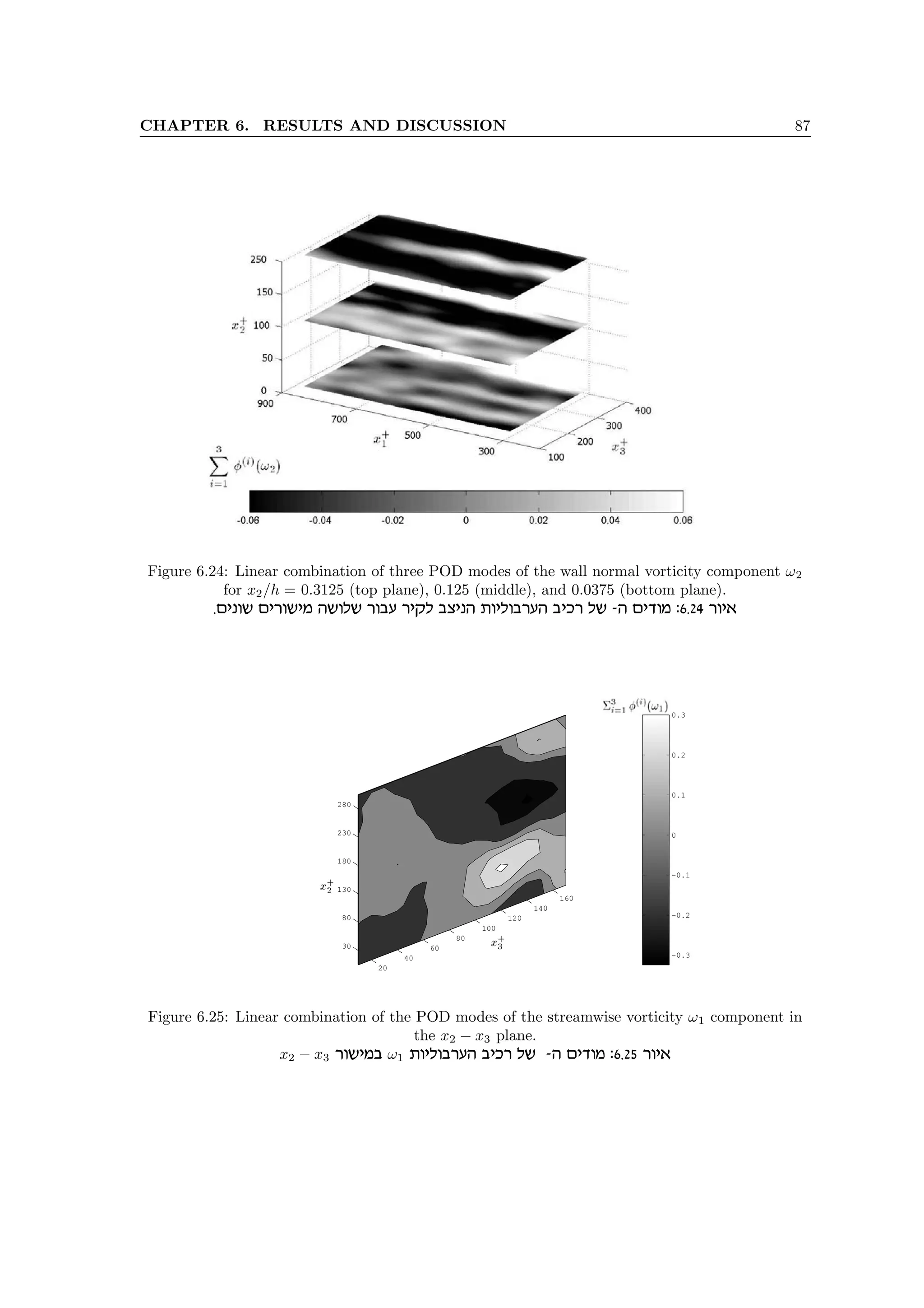

6.24 Linear combination of three POD modes of the wall normal vorticity component ω2

for x2/h = 0.3125 (top plane), 0.125 (middle), and 0.0375 (bottom plane). . . . . . . 87

6.25 Linear combination of the POD modes of the streamwise vorticity ω1 component in

the x2 − x3 plane. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

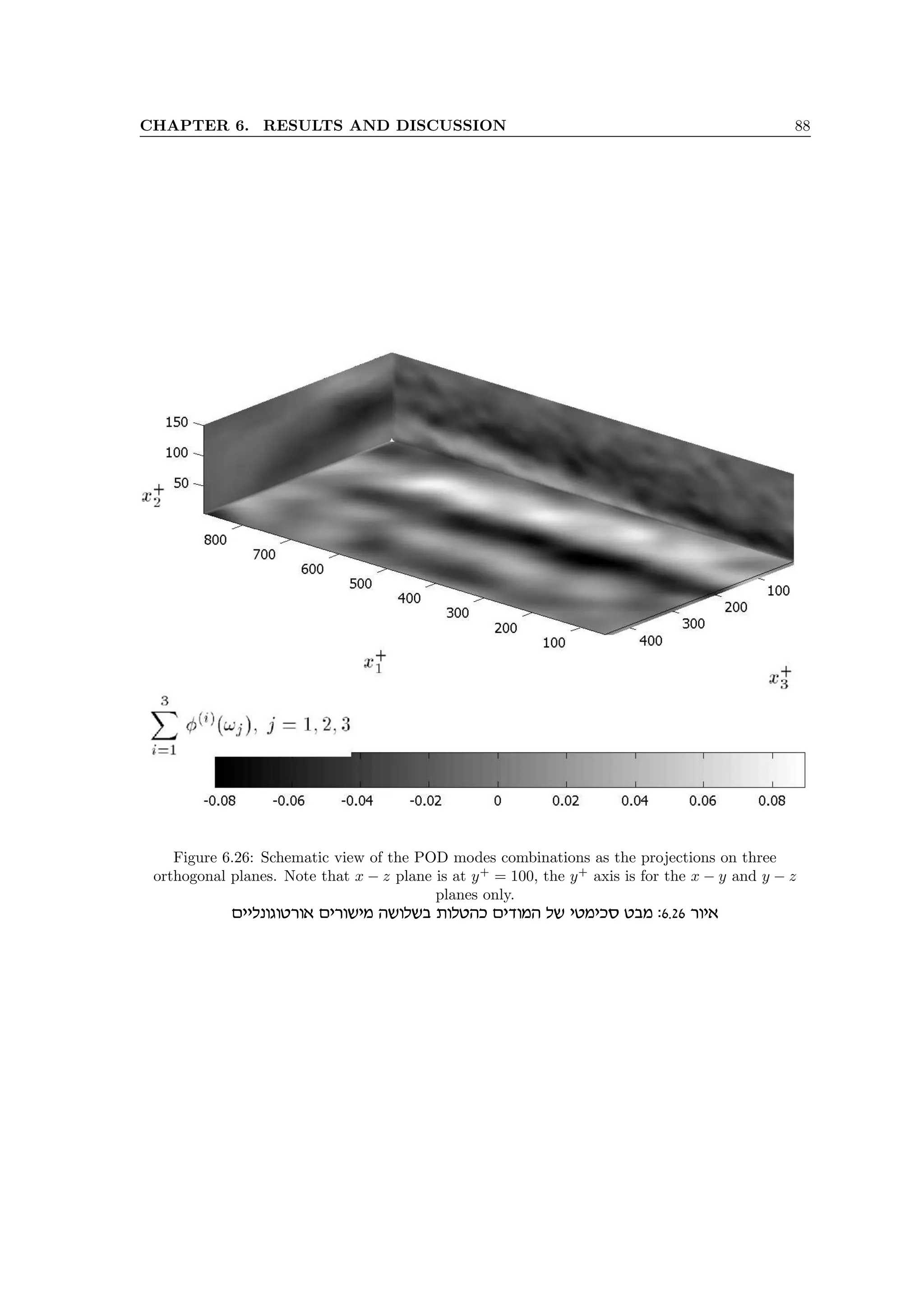

6.26 Schematic view of the POD modes combinations as the projections on three orthog-

onal planes. Note that x − z plane is at y+

= 100, the y+

axis is for the x − y and

y − z planes only. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

6.27 Streamwise velocity average profiles measured by using XPIV (-o) and box-plot of the

PIV measurements in separate y planes(|-[]-|). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

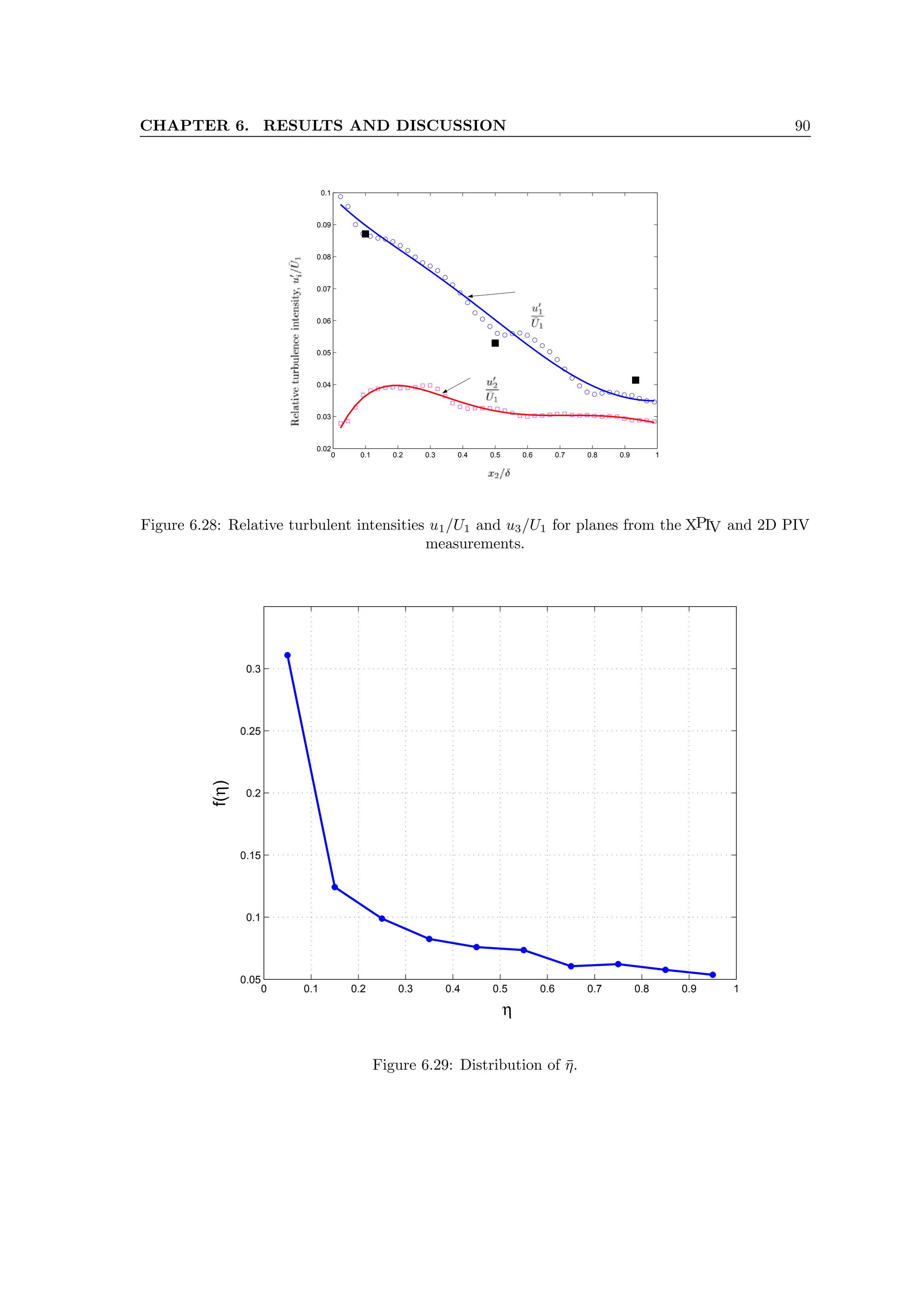

6.28 Relative turbulent intensities u1/U1 and u3/U1 for planes from the XPIV and 2D PIV

measurements. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

6.29 Distribution of η̄. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

B.1 Standard PIV image and the analysis with InsightTM

software . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

B.2 Comparison of the results calculated by InsightTM

and URAPIV software. . . . . . 100

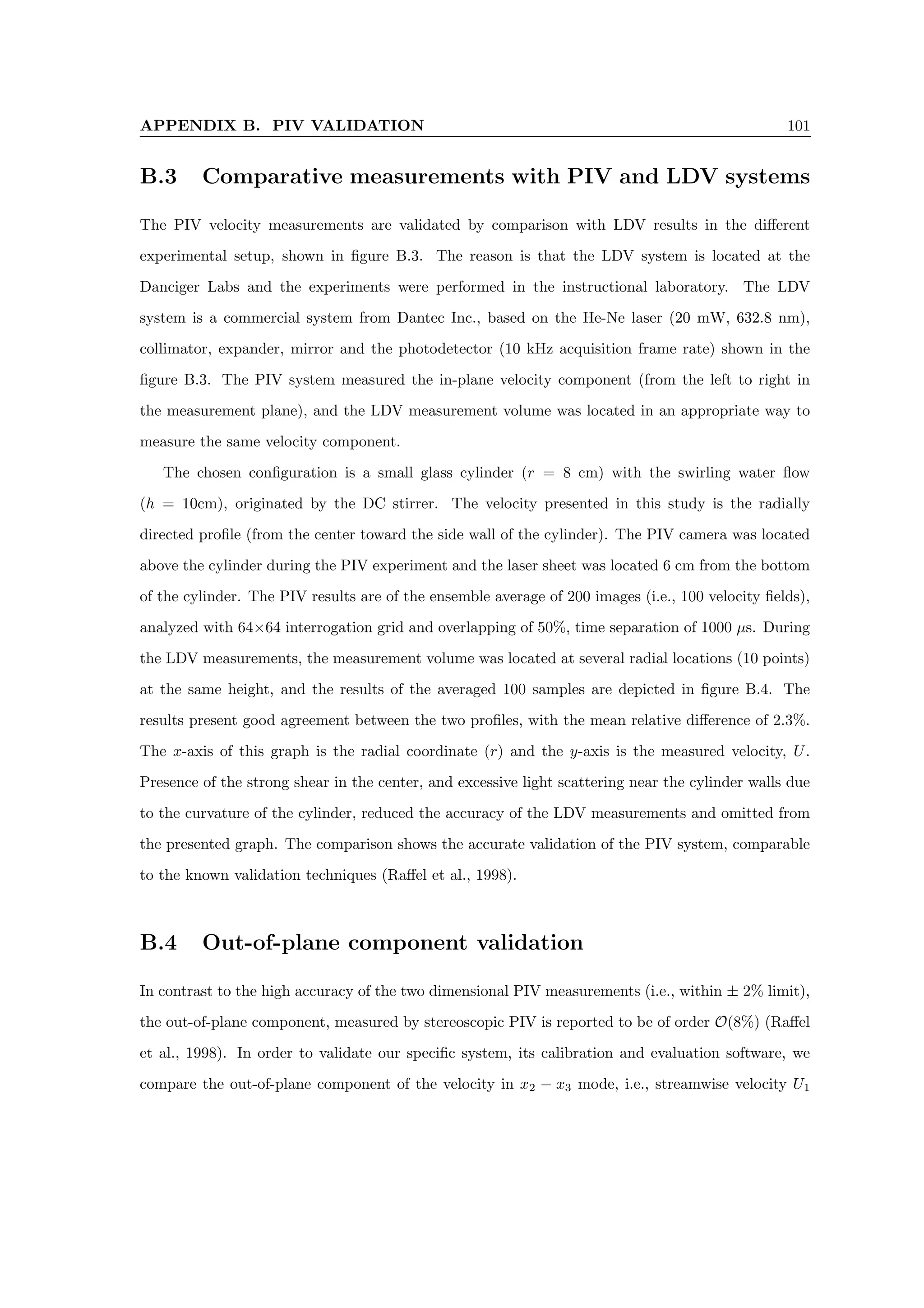

B.3 Schematic view of the PIV and LDV measurement systems and flow configuration. . 102

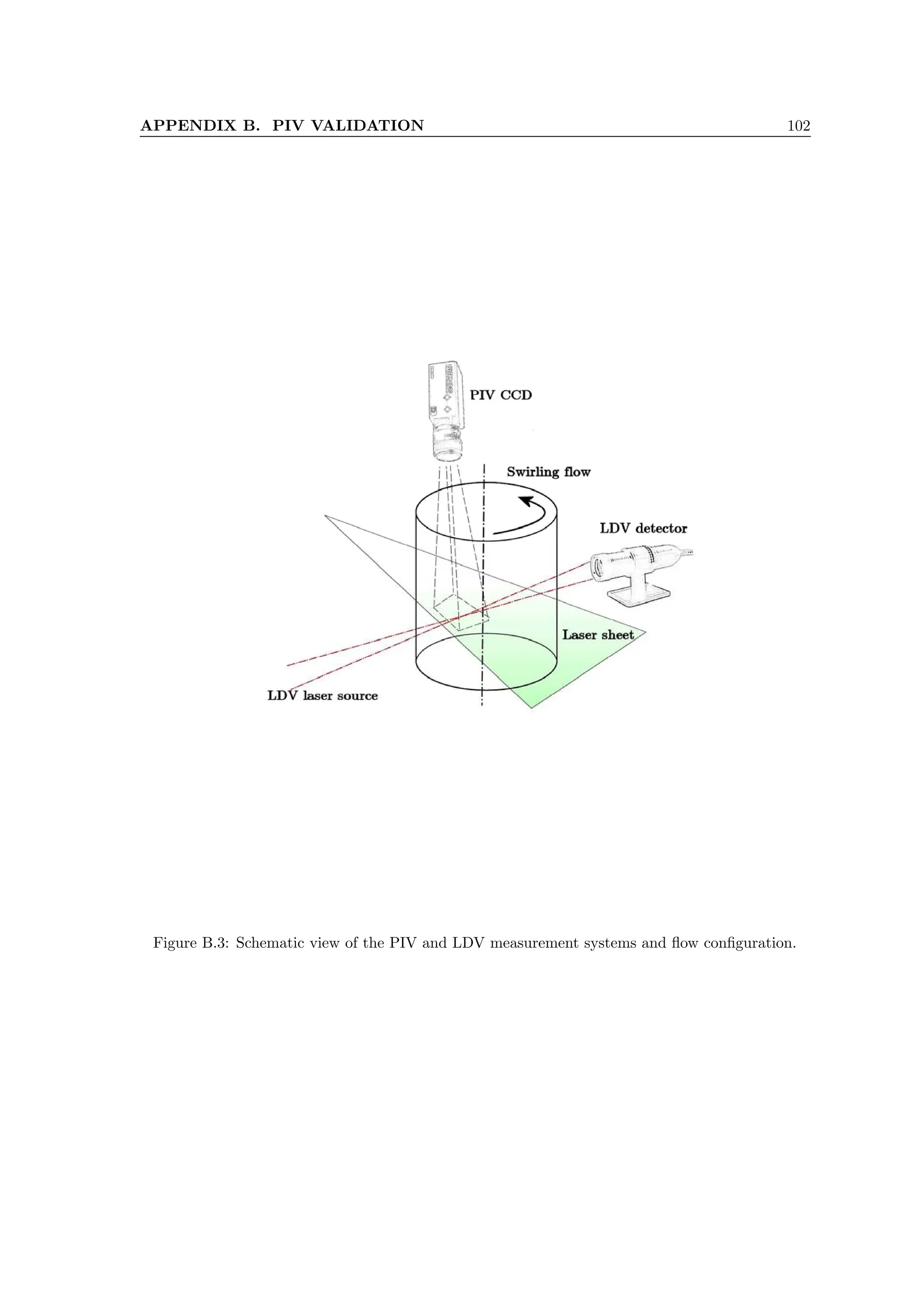

B.4 Velocity results of the PIV versus LDV measurement results. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

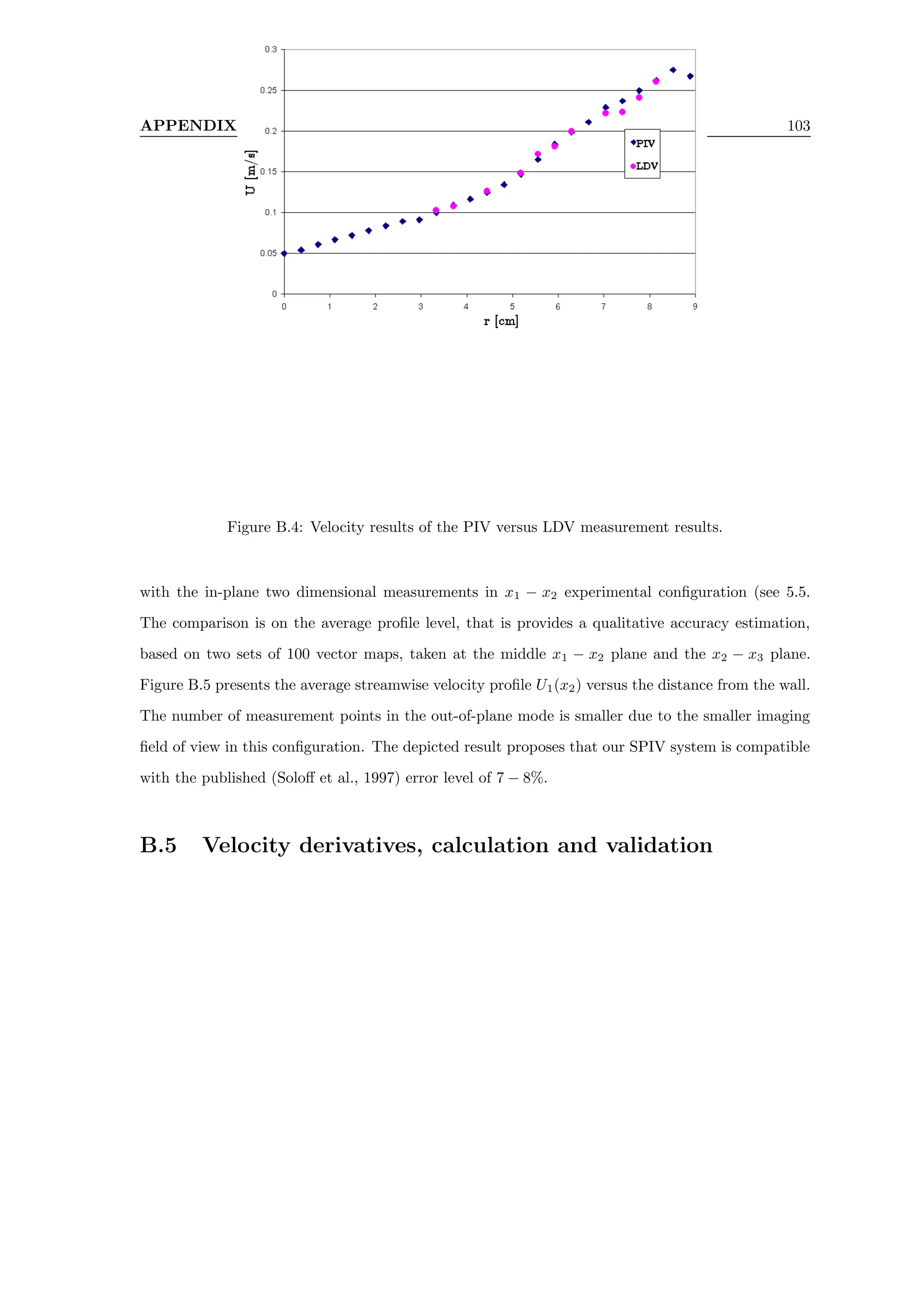

B.5 Velocity profile measured in x − y (+) and in y − z (•) configurations. . . . . . . . . 104

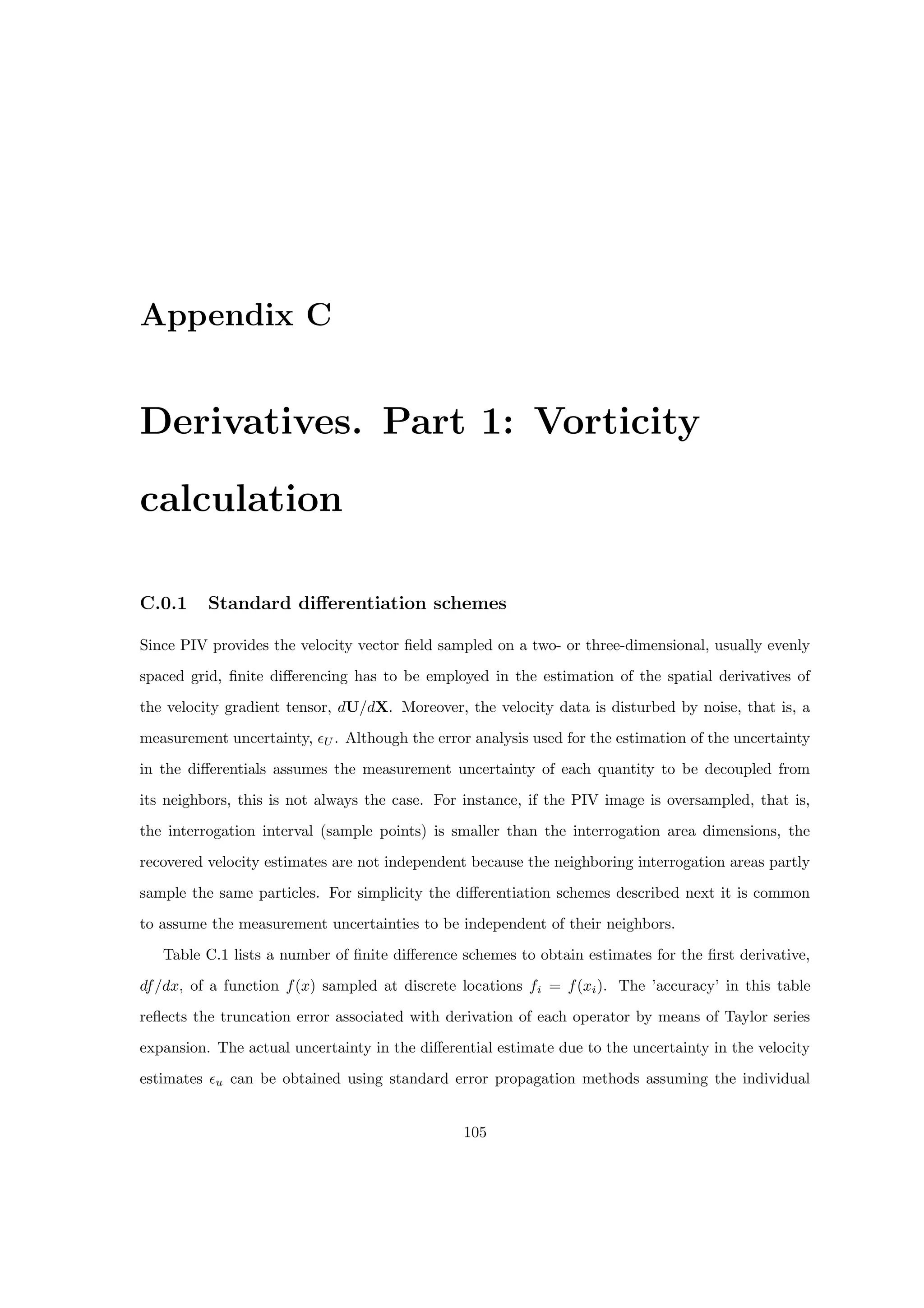

C.1 Taylor-Green vortex flow field and its vorticity. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

C.2 Relative error as a function of simulation runs number for (a) 2%, (b) 5% and (c)

7.5% velocity noise level. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112

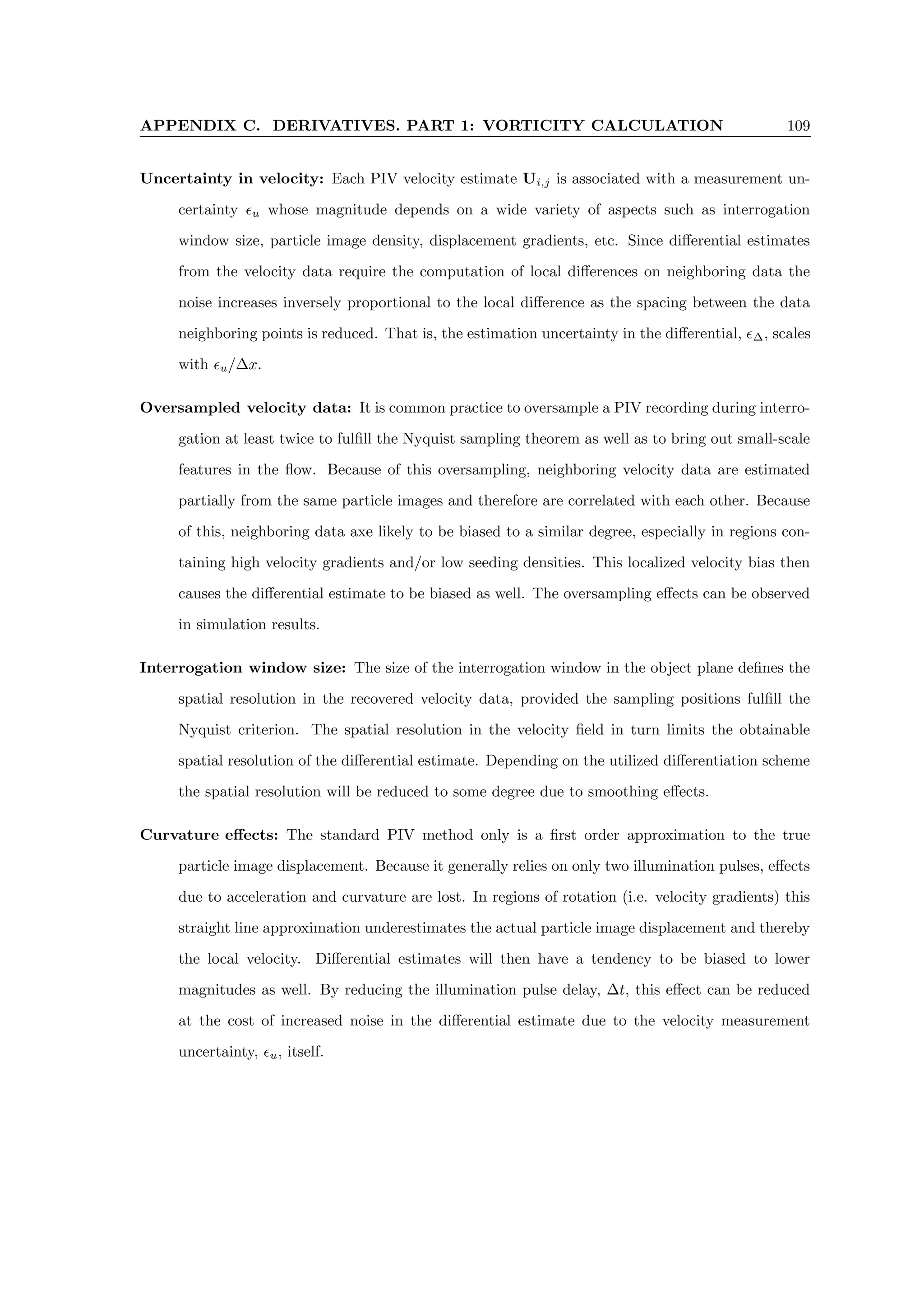

C.3 Relative error as a function of additive noise level for (a) 100, (b) 500, and (c) 1000

simulation runs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

C.4 Mean value of the out-of-plane strain estimation (the mean error of the continuity

equation) for the 500 simulation runs and 5% additive noise level. The plot consists

of the results for the ’Center’ - upper left, ’Richardson’ - upper right, ’Least Squares’

- lower left, and ’Circulation’ calculation scheme at the lower right corner. . . . . . . 114](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-10-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 16

2.4.6 Calculations

Lumley (1970) introduced the Karhunen-Loéve decomposition method of the random functions to

the turbulent flow research to use it as an unbiased method for discrete data set, such as experimental

or numerical data. It is known that in the continuous case the probability density function (PDF)

provides the full description of the of continuous random functions. The integral of the PDF defines

the mean value of the random vector, and the distribution of the random vectors around the mean

is determined by using the covariance matrix. The optimal presentation of the random set defined

above is based on the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the the covariance matrix.

In the discrete case (such as PIV or DNS data) the flow quantities are presented as the set

of (random) vectors that approves the second order statistical property – the existence of optimal

representation by eigenfunctions. If the set of M vectors of length n is presented as:

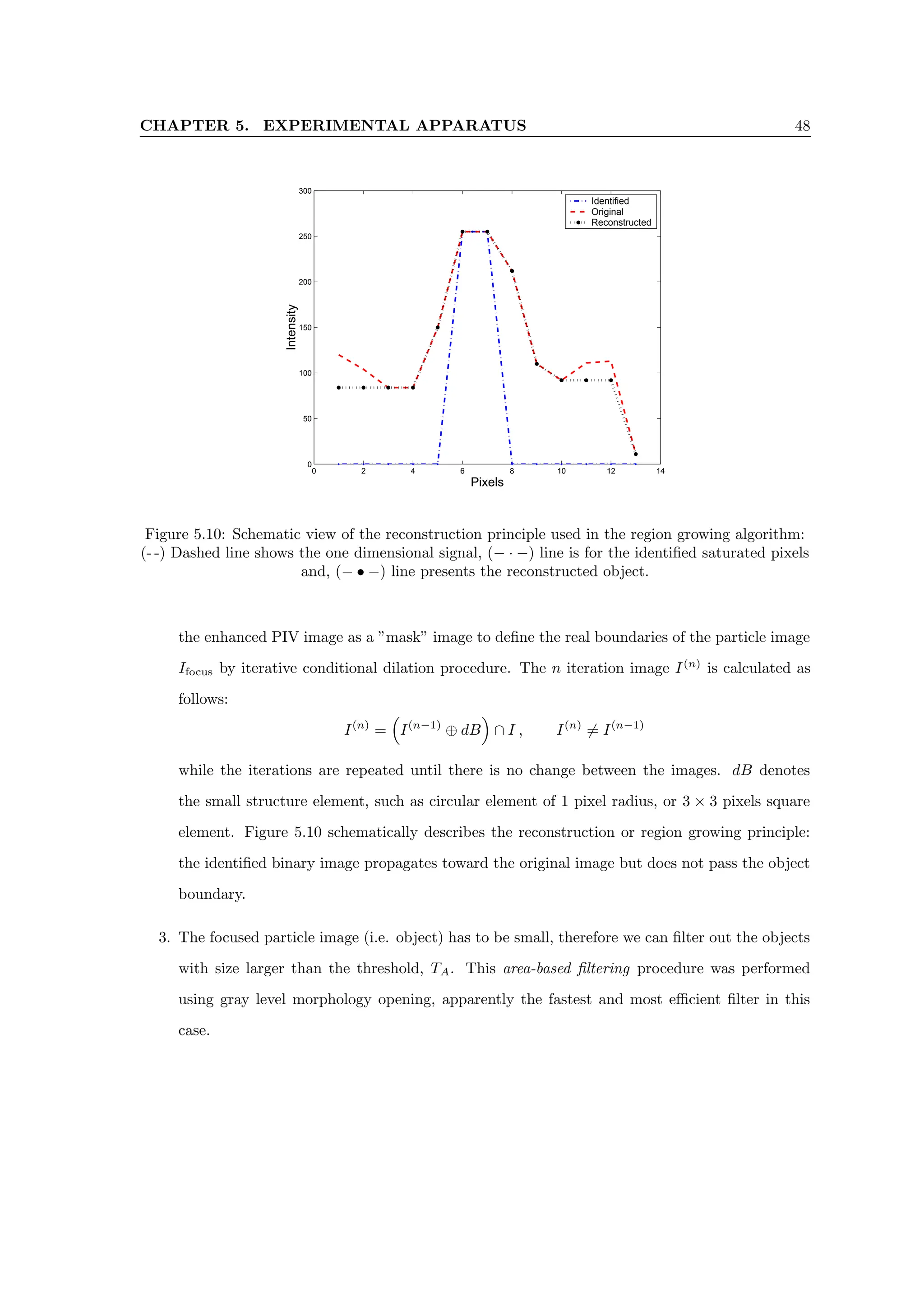

{ui}

M

i=1 , ui = [u1, u2, . . . , un]T

(2.13)

then the discrete approximation of the autocorrelation kernel R is known as the covariance matrix:

C =

1

M

M

X

i=1

ui · uT

i (2.14)

Herein we assume the the data is the field of fluctuations, treated as random data. If the data

analysis is of the instantaneous flow quantity (such as instantaneous velocity or vorticity, for in-

stance), then first the statistical average (denoted by¯or by h·i, interchangeably) is calculated by

the approximation:

ū =

1

M

M

X

i=1

ui (2.15)

and then is subtracted from the data vector set:

ui = ui − ū (2.16)

Then the analysis is done by using the fluctuating field, similar to the spatio-temporal data analysis

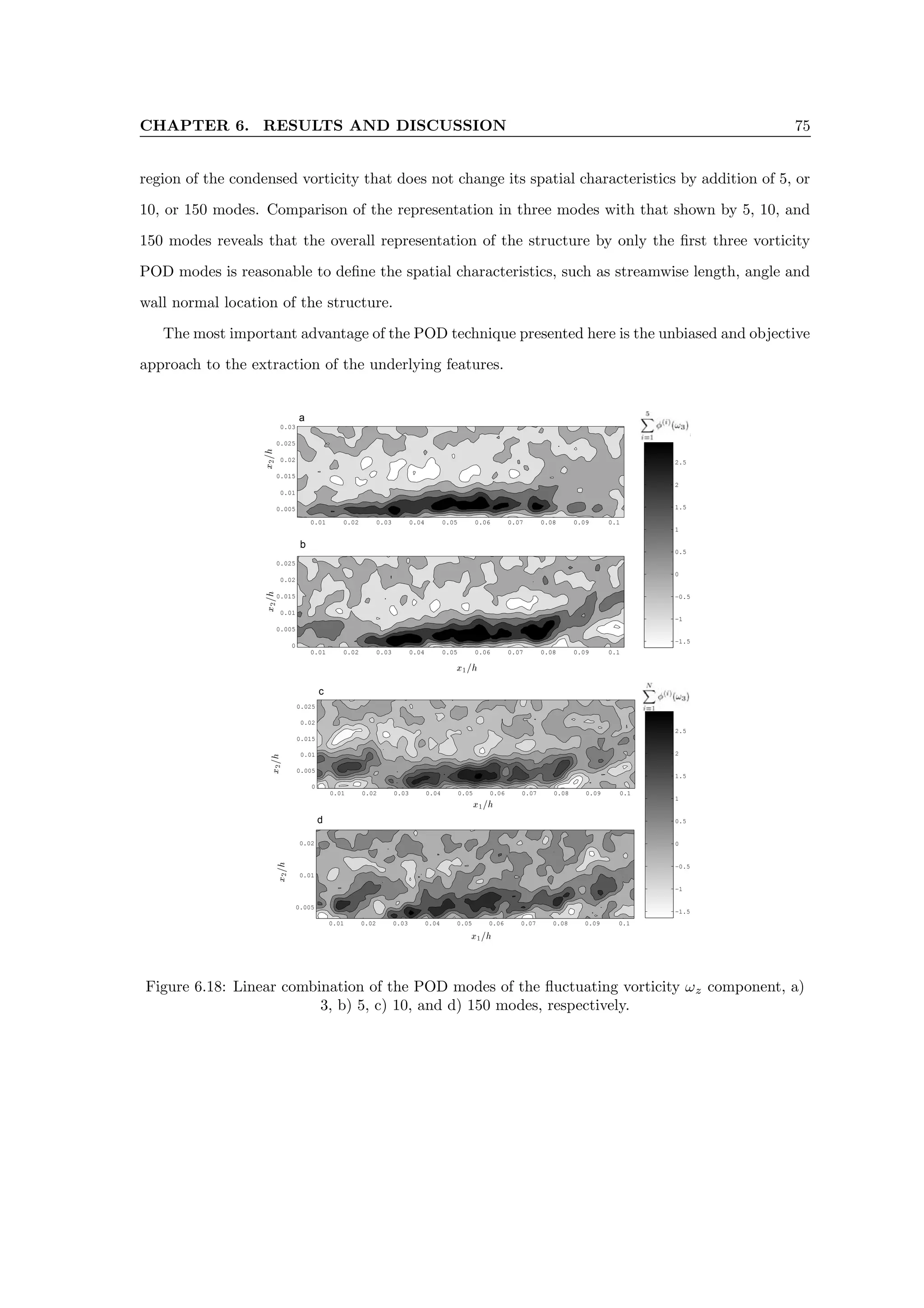

performed by Heiland (1992). We point out that the covariance matrix is an N × N matrix, where

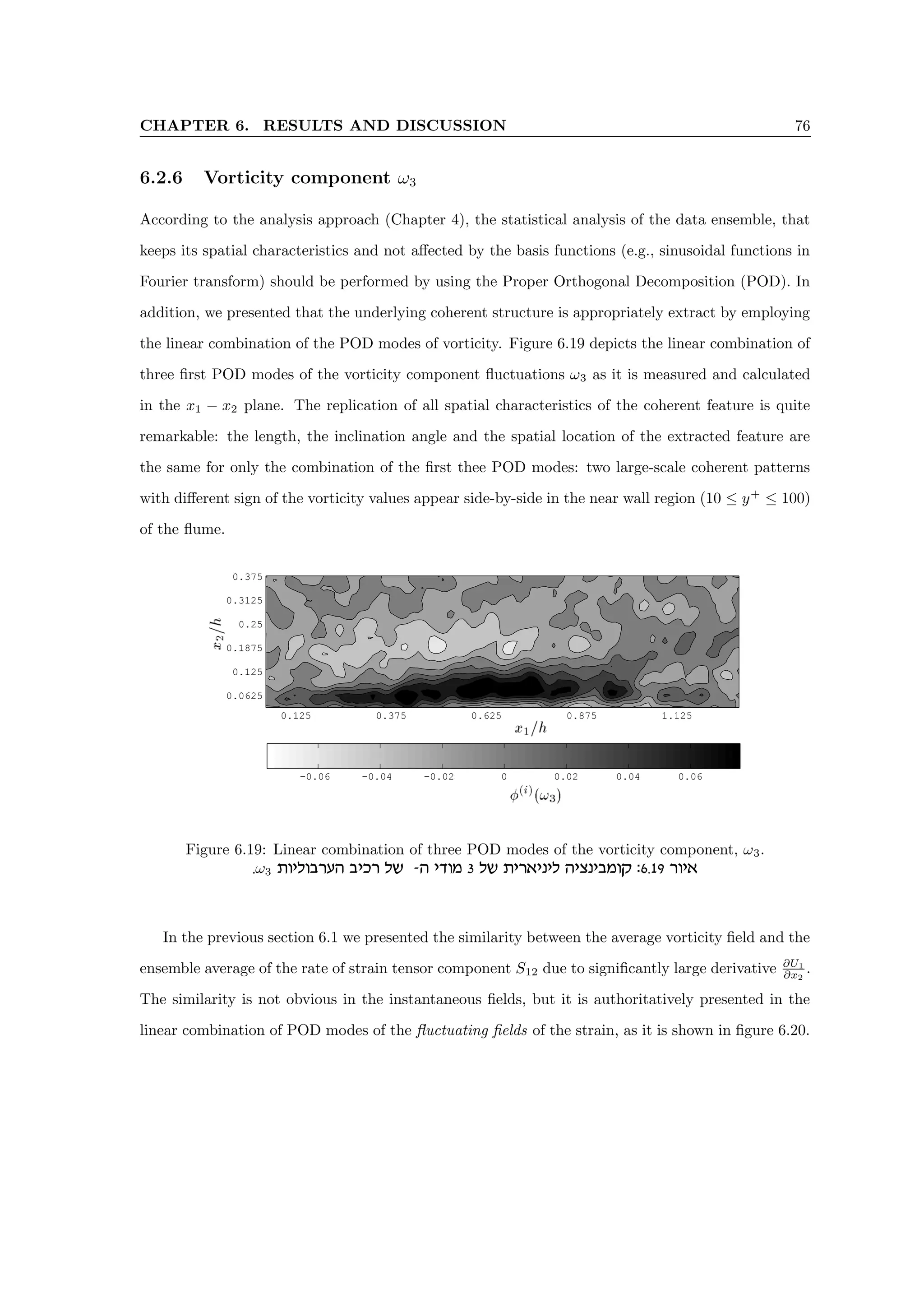

N is the spatial resolution of a vector (e.g., for the PIV data it is the total number of the vectors

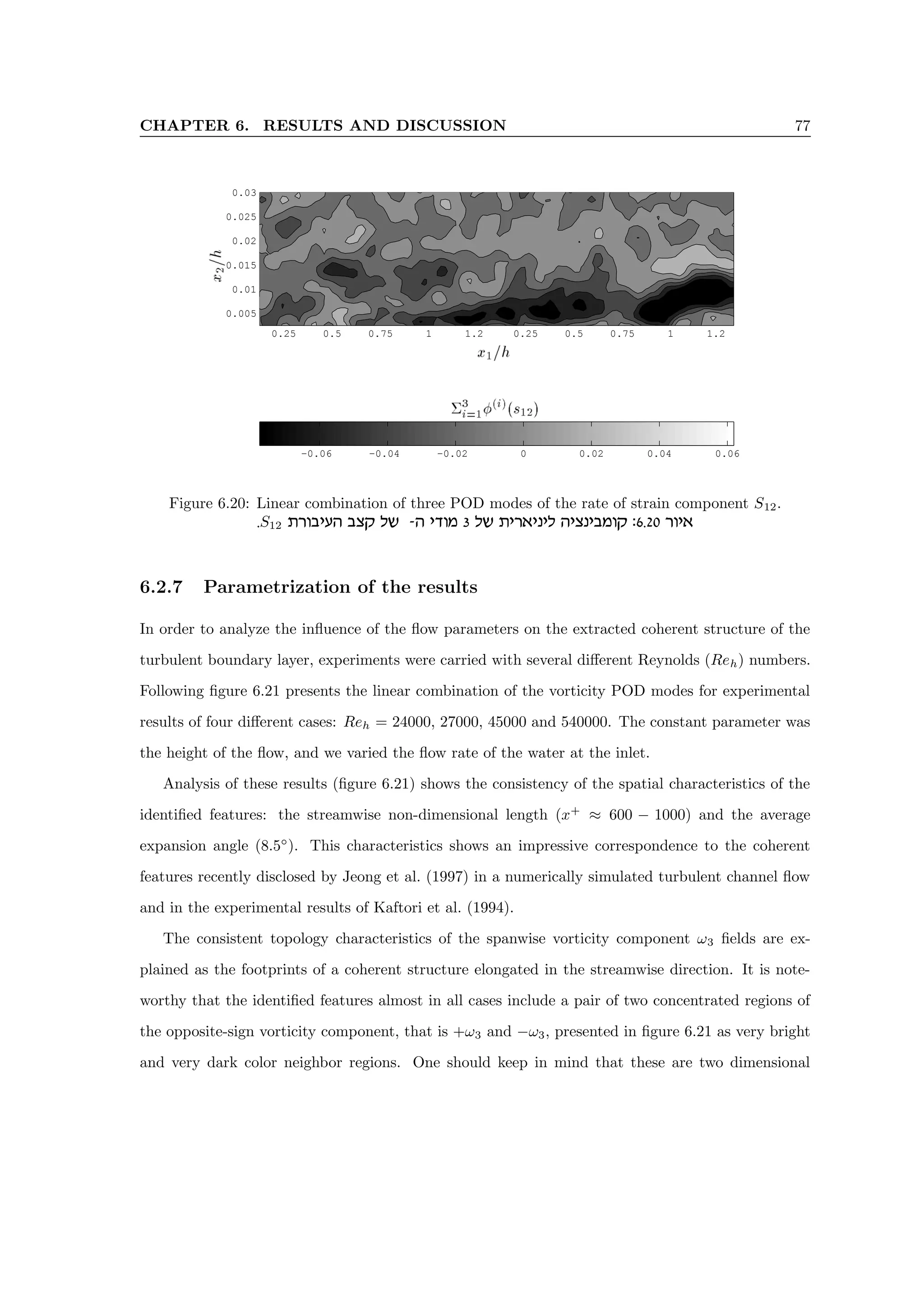

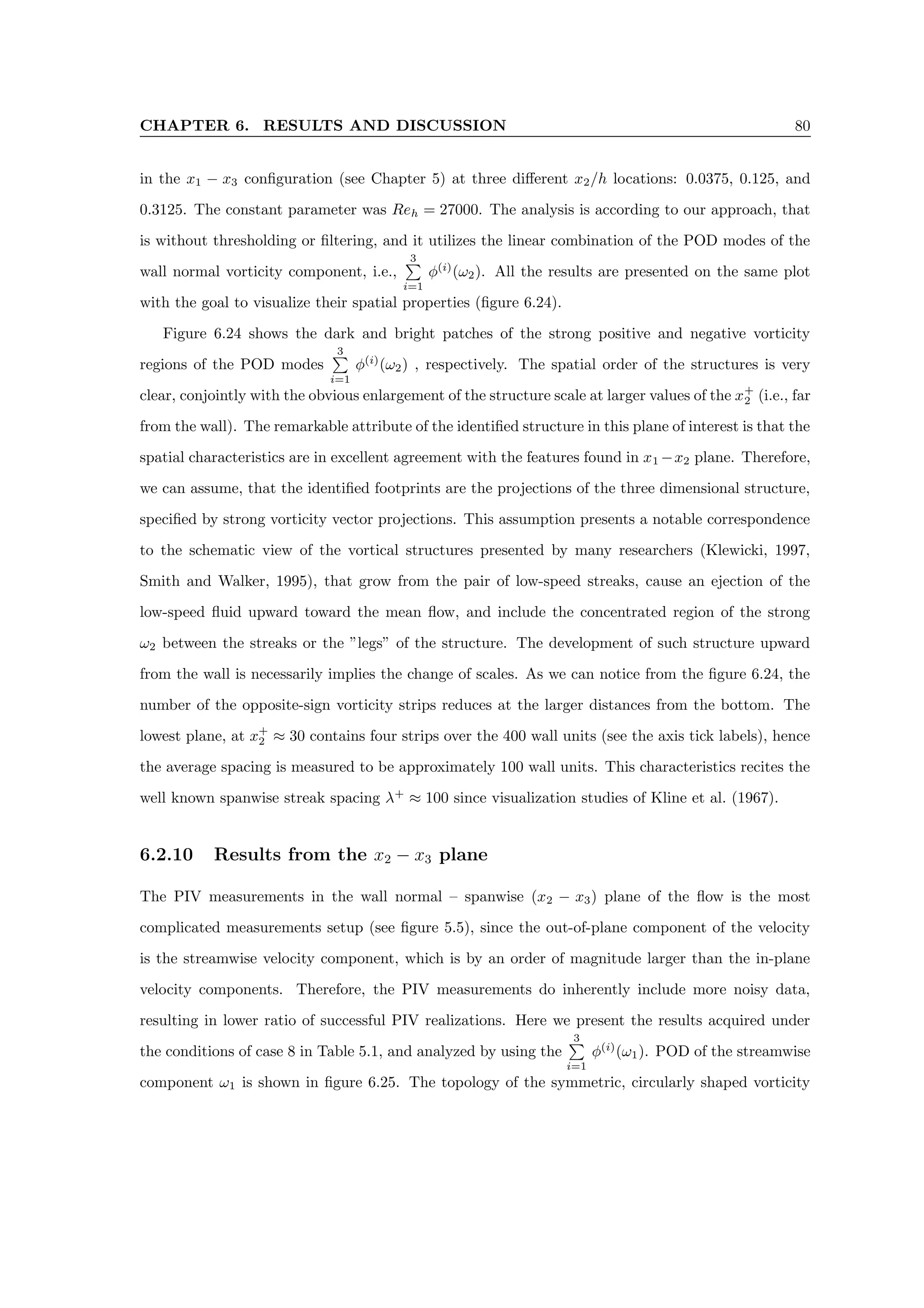

within the flow field). For large N (e.g., N = 1000 vectors for the usual PIV analysis), the covariance

matrix becomes too large for massive computation. In practice, most of the POD analysis, shown](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-28-2048.jpg)

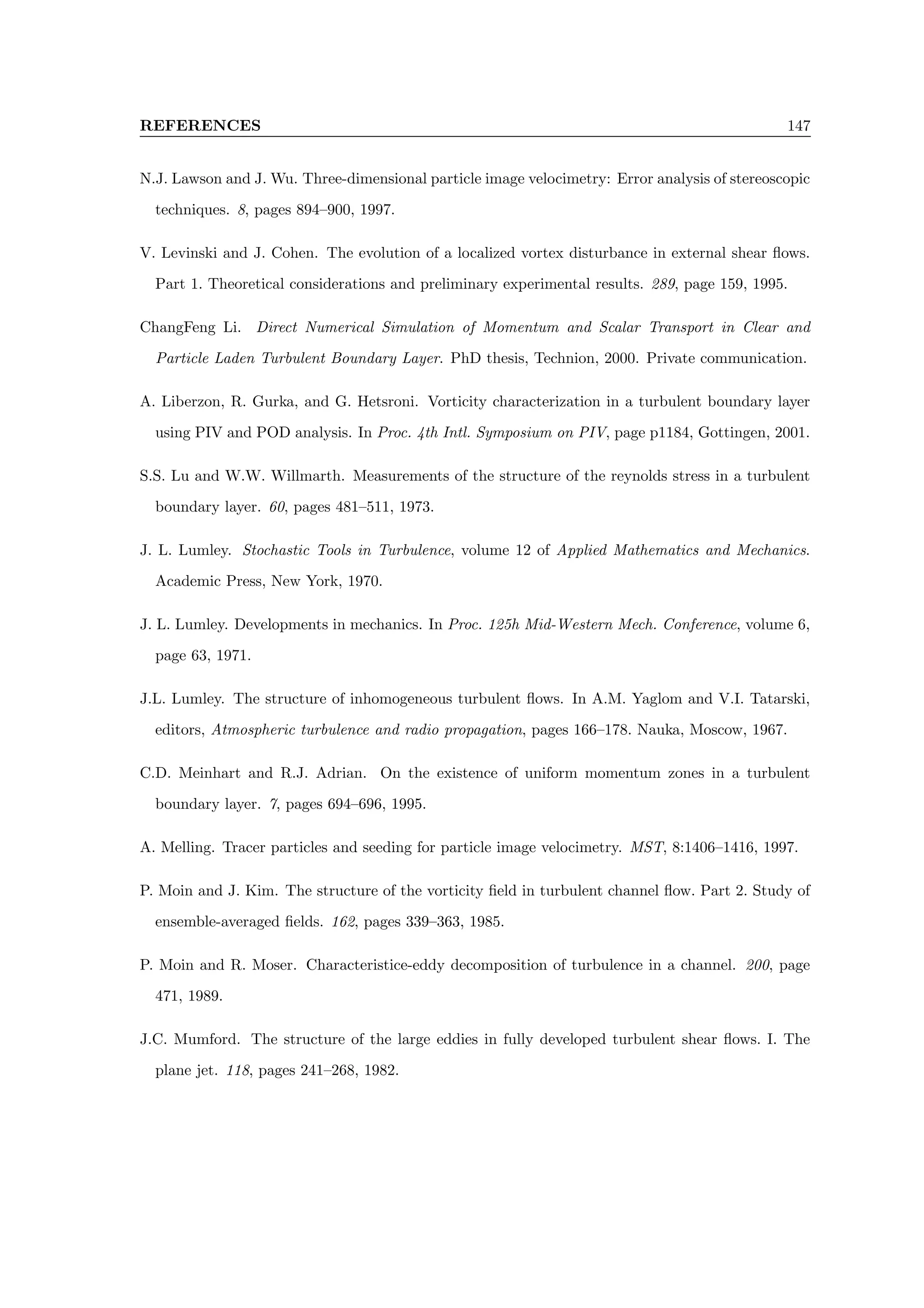

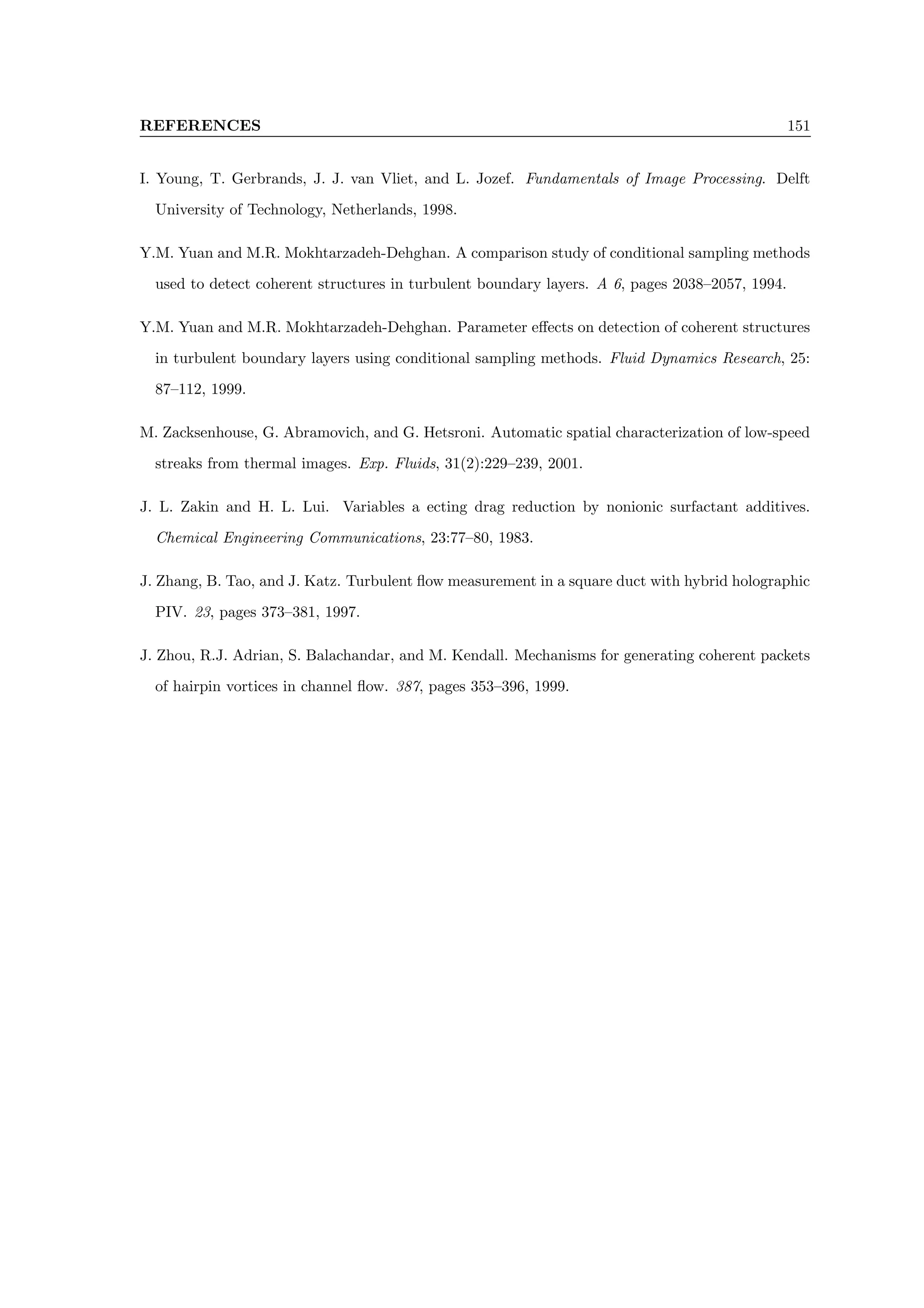

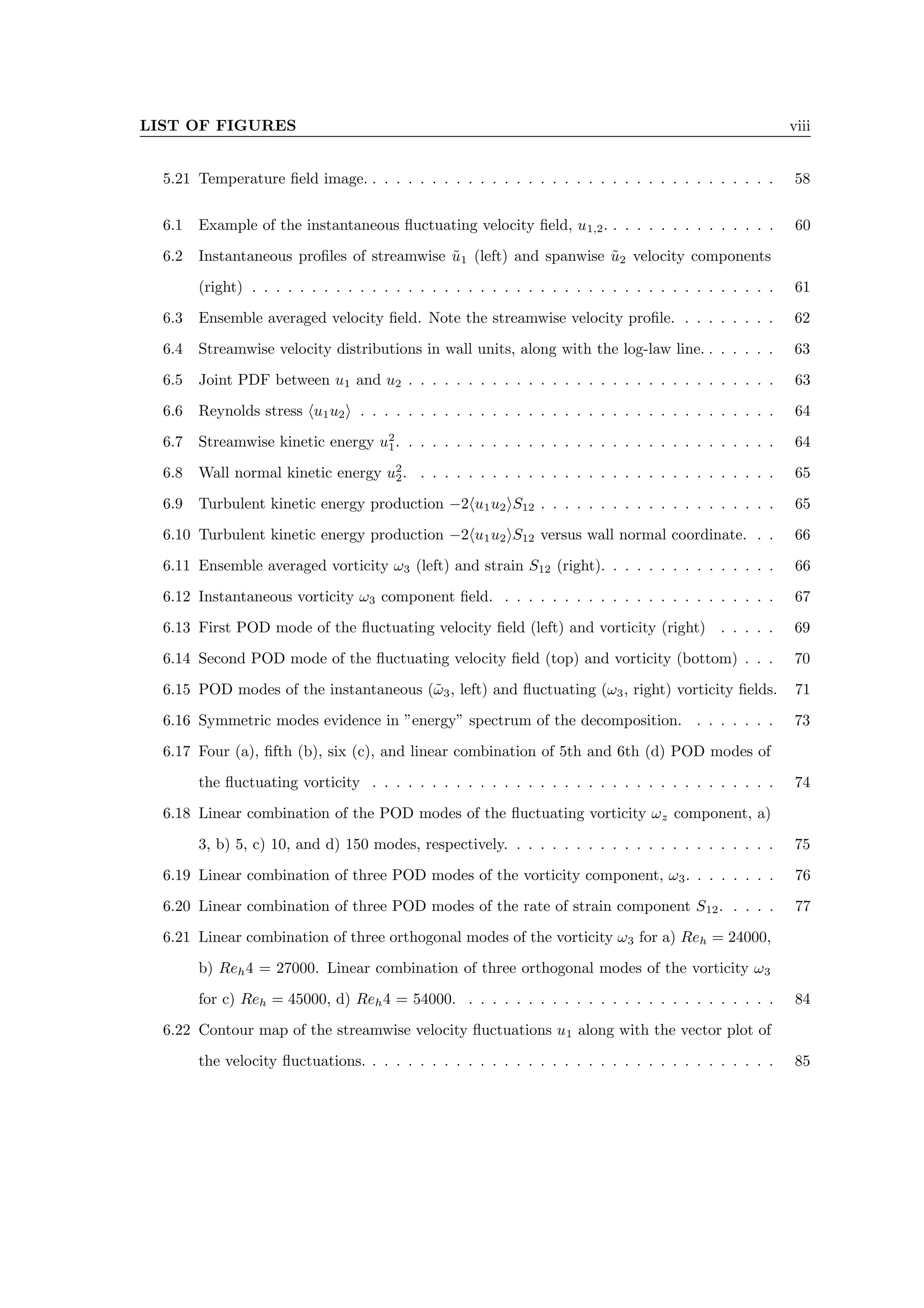

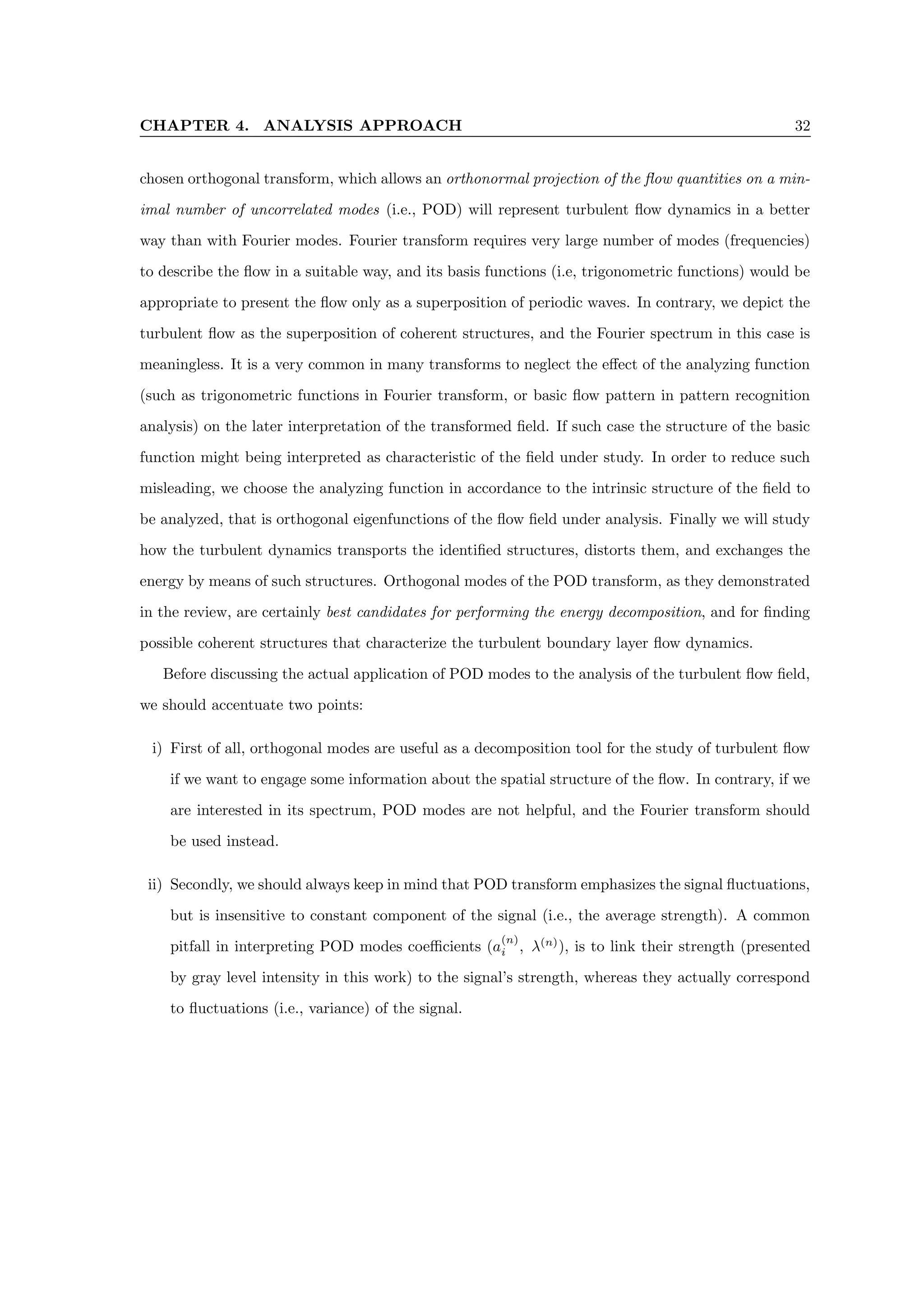

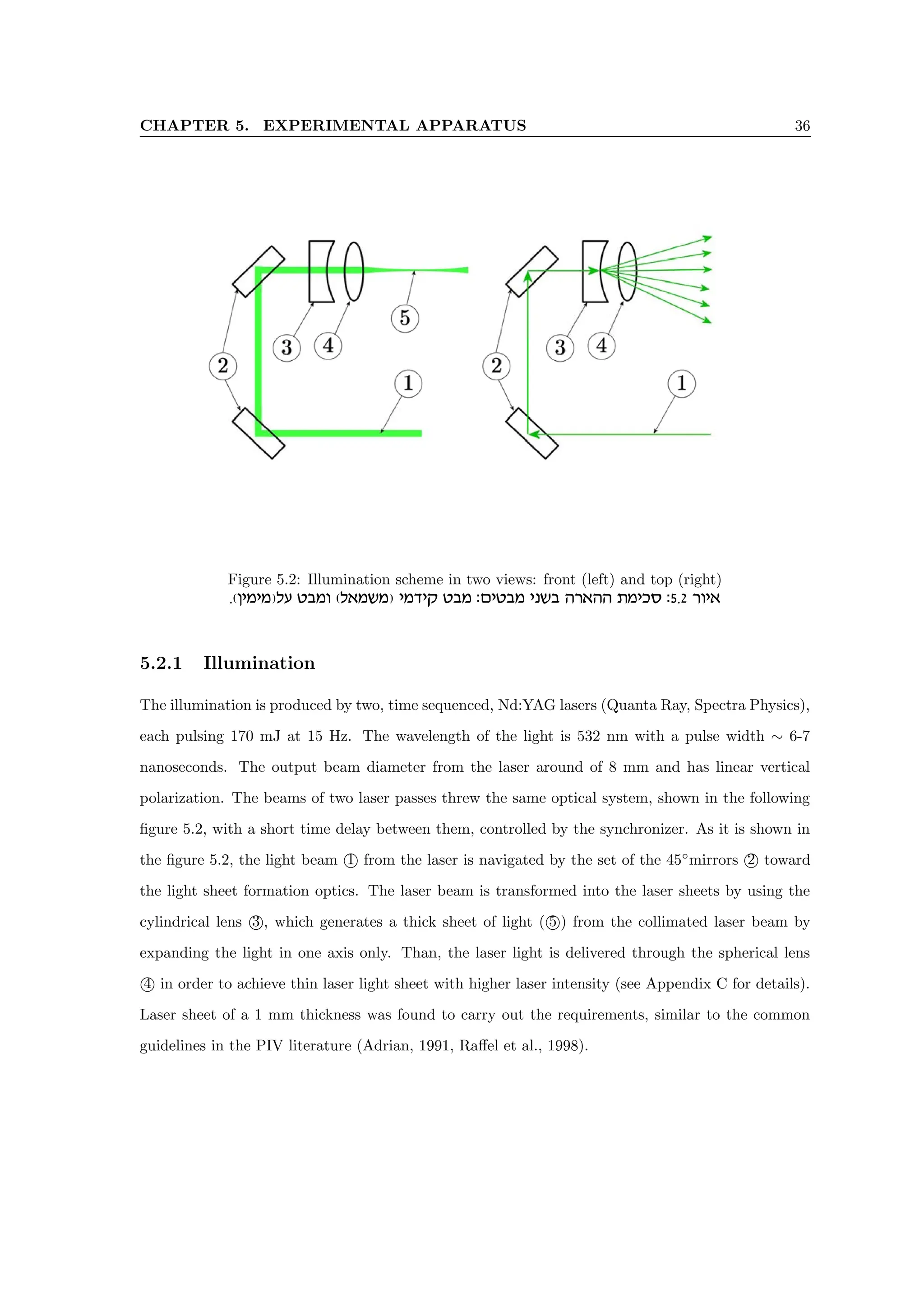

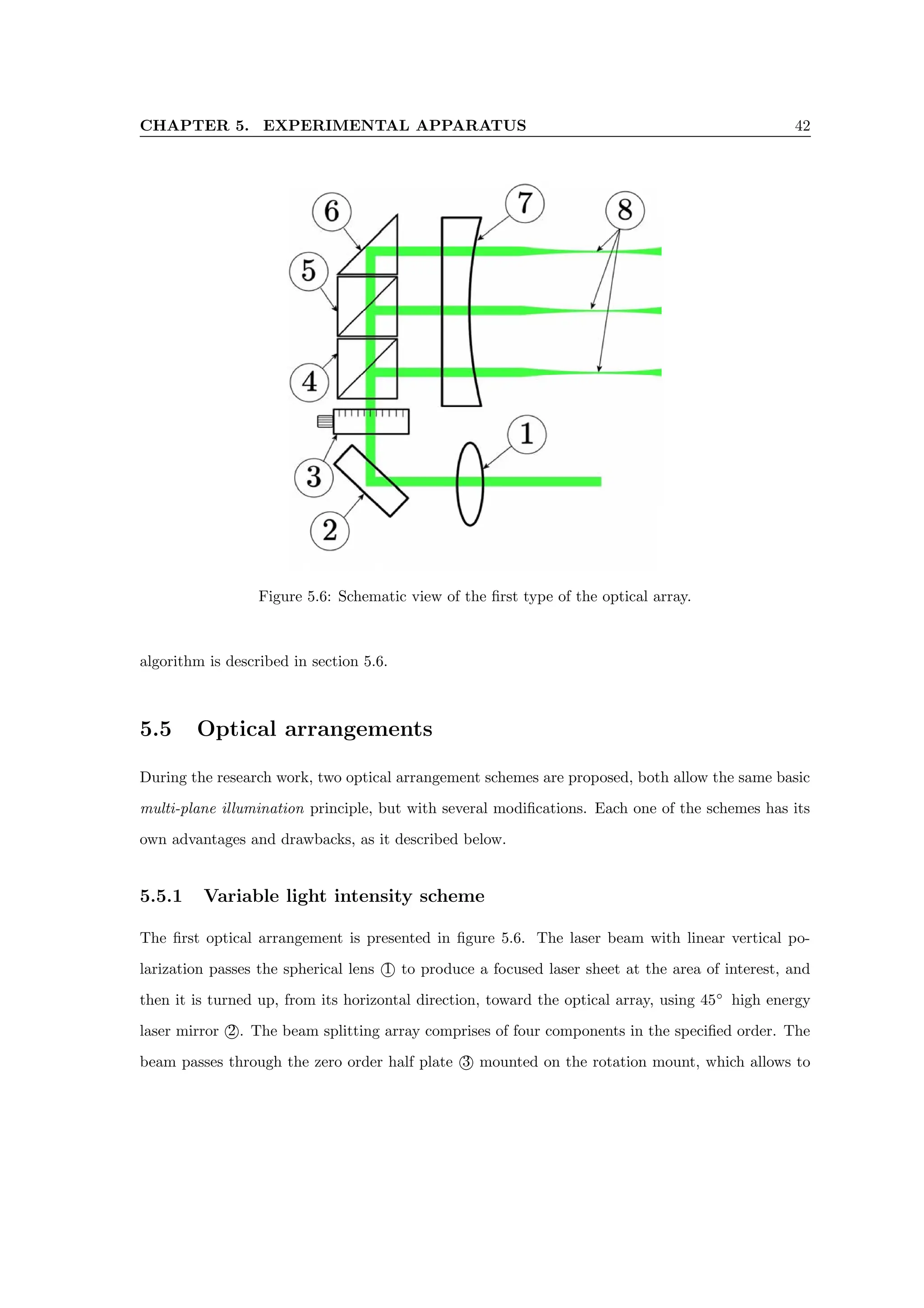

![CHAPTER 5. EXPERIMENTAL APPARATUS 41

Case No. Plane Coordinates [m] Reh Um [m/s] u∗

[m/s]

1 x − y z = 0.15 21000 0.21 0.011

2 x − y z = 0.15 27000 0.27 0.013

3 x − y z = 0.15 45000 0.45 0.022

4 x − y z = 0.15 57000 0.57 0.027

5 x − z y = 0.003 27000 0.24 0.013

6 x − z y = 0.01 27000 0.24 0.013

7 x − z y = 0.025 27000 0.24 0.013

8 y − z x = 2.50 27000 0.24 0.011

Table 5.1: Experimental parameters of the StereoPIV.

.miieqipd i‘pze mixhnxt :5.1 dlah

5.4 XPIV – Multi-plane Stereoscopic Particle Image Velocime-

try

In this section, the three dimensional extension of the stereoscopic PIV method, XPIV - Multiplane

SPIV is presented, along with the optical scheme, basic principles and image processing algorithm.

The quality of the velocity data is evaluated by using the velocity profiles, turbulent intensity and

the continuity equation characteristics.

5.4.1 Introduction

Experimental investigation of turbulent flows requires techniques that allow three dimensional mea-

surements with high spatial and temporal resolutions. PIV appears to be an appropriate basis for

three dimensional velocity measurements, as it is presented in the literature review, Section 2.3. The

technique has only technological limitations to achieve a temporal resolution due to the illumination

source (lasers) and recording media (CCD) frequencies which are available today.

Understanding the drawbacks and advantages of the obtainable measurement systems led to

the development of the multi-plane stereoscopic velocimetry technique, XPIV . The technique ap-

plies the principles of multi-sheet illumination, stereoscopic imaging and particle image defocusing.

The experimental technique implemented with a stereoscopic PIV system (Section 5.2), based on

additional optics and image processing algorithm.

Section 5.5 presents the optical configurations implemented during the research. Image processing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-53-2048.jpg)

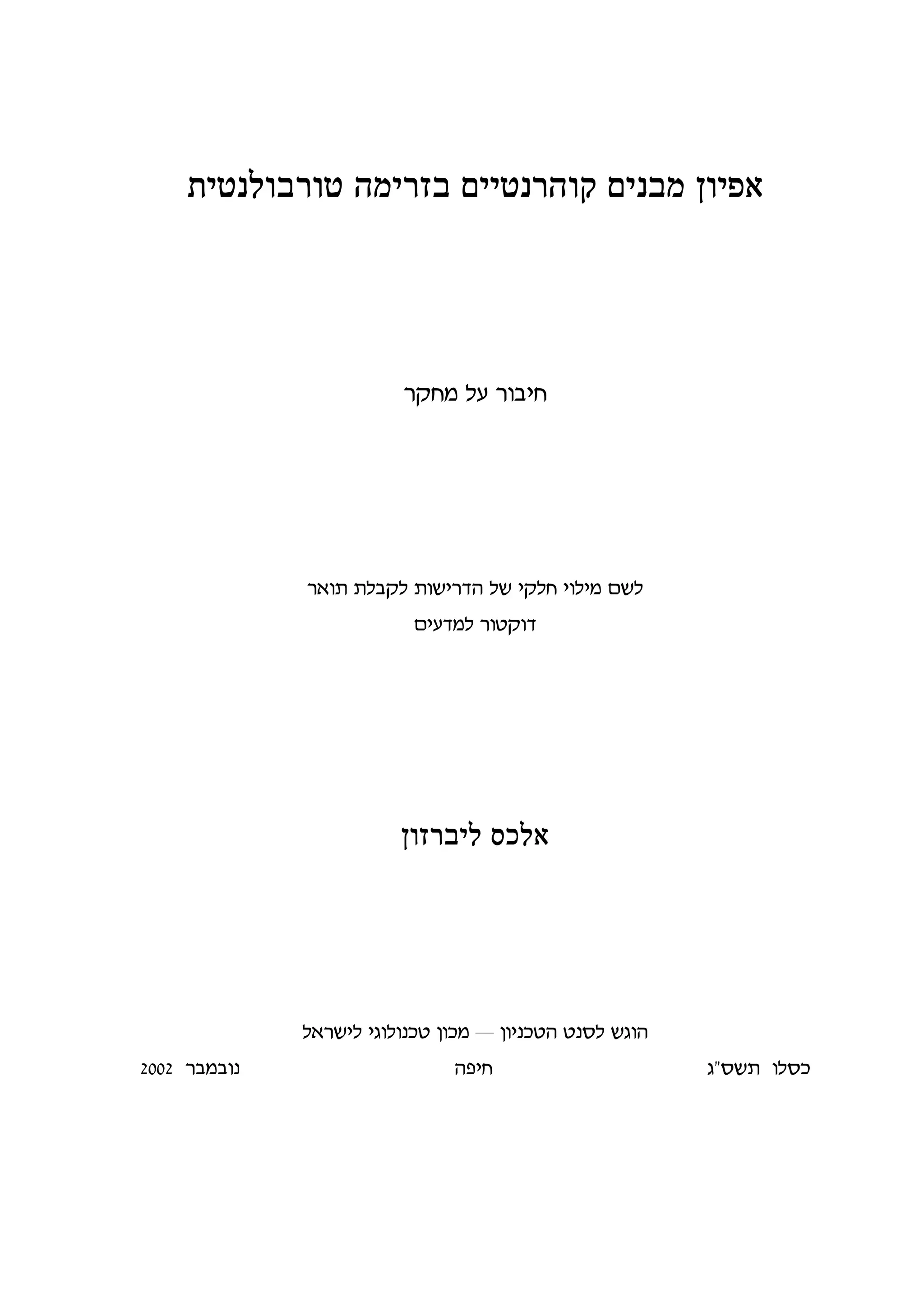

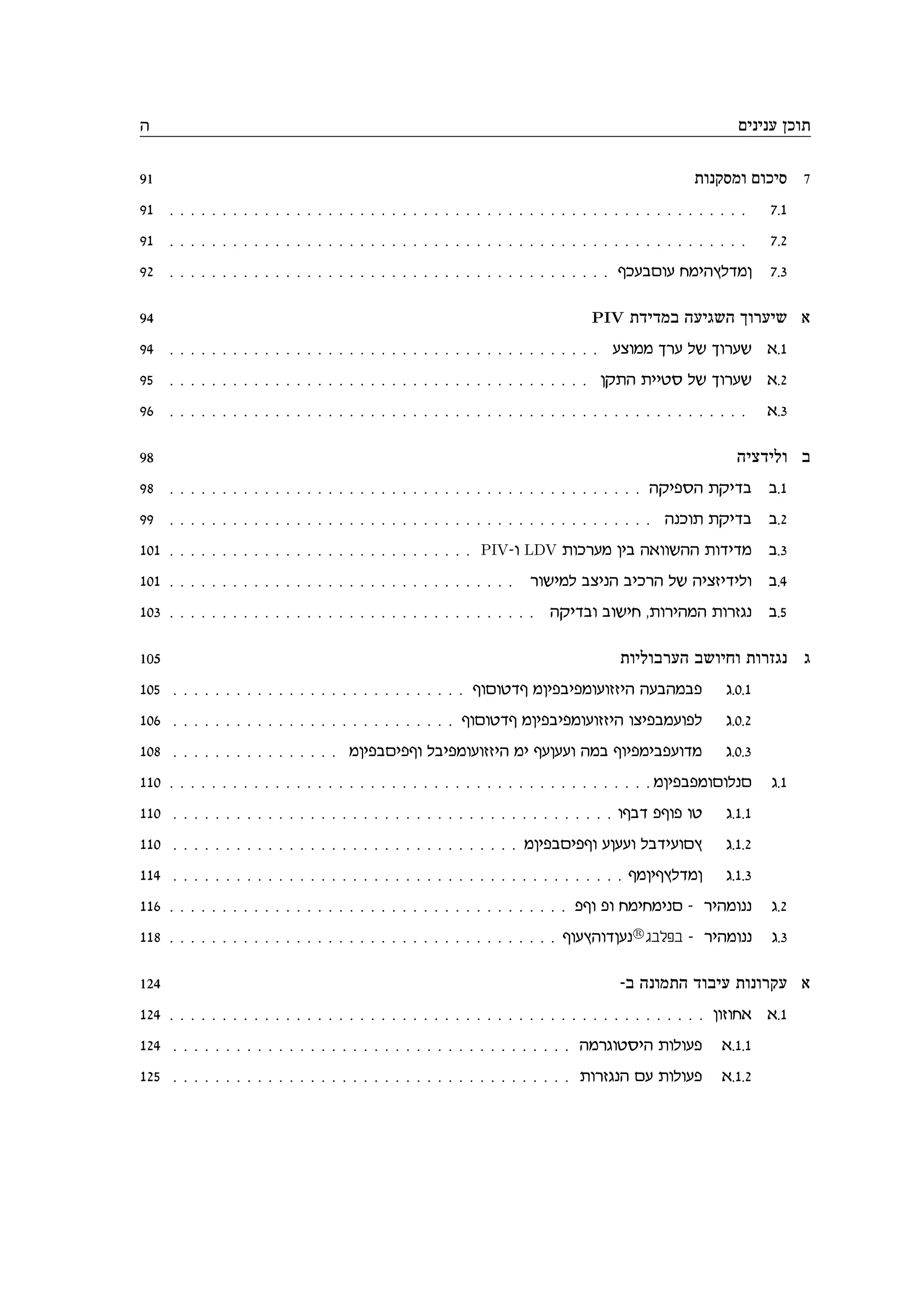

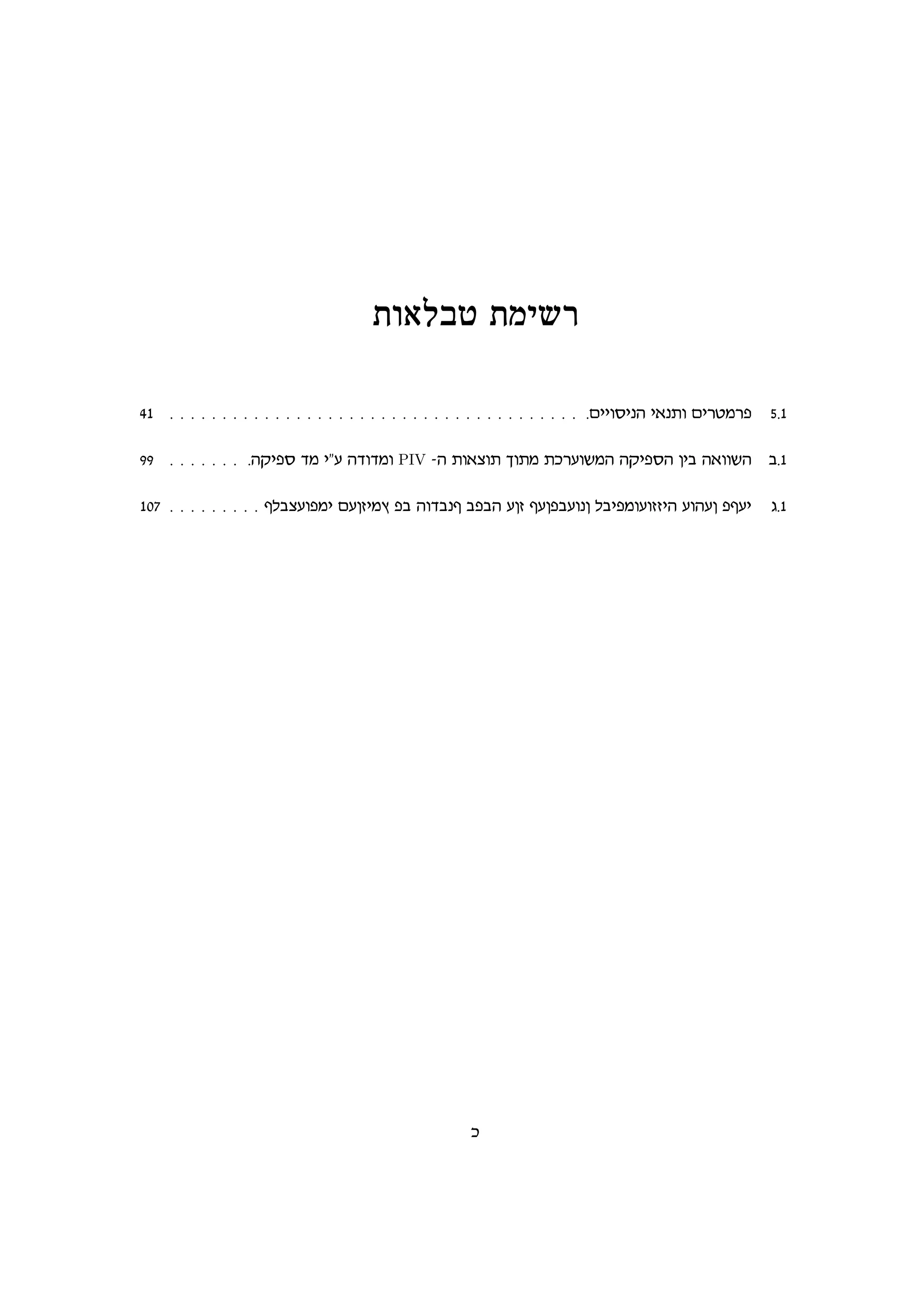

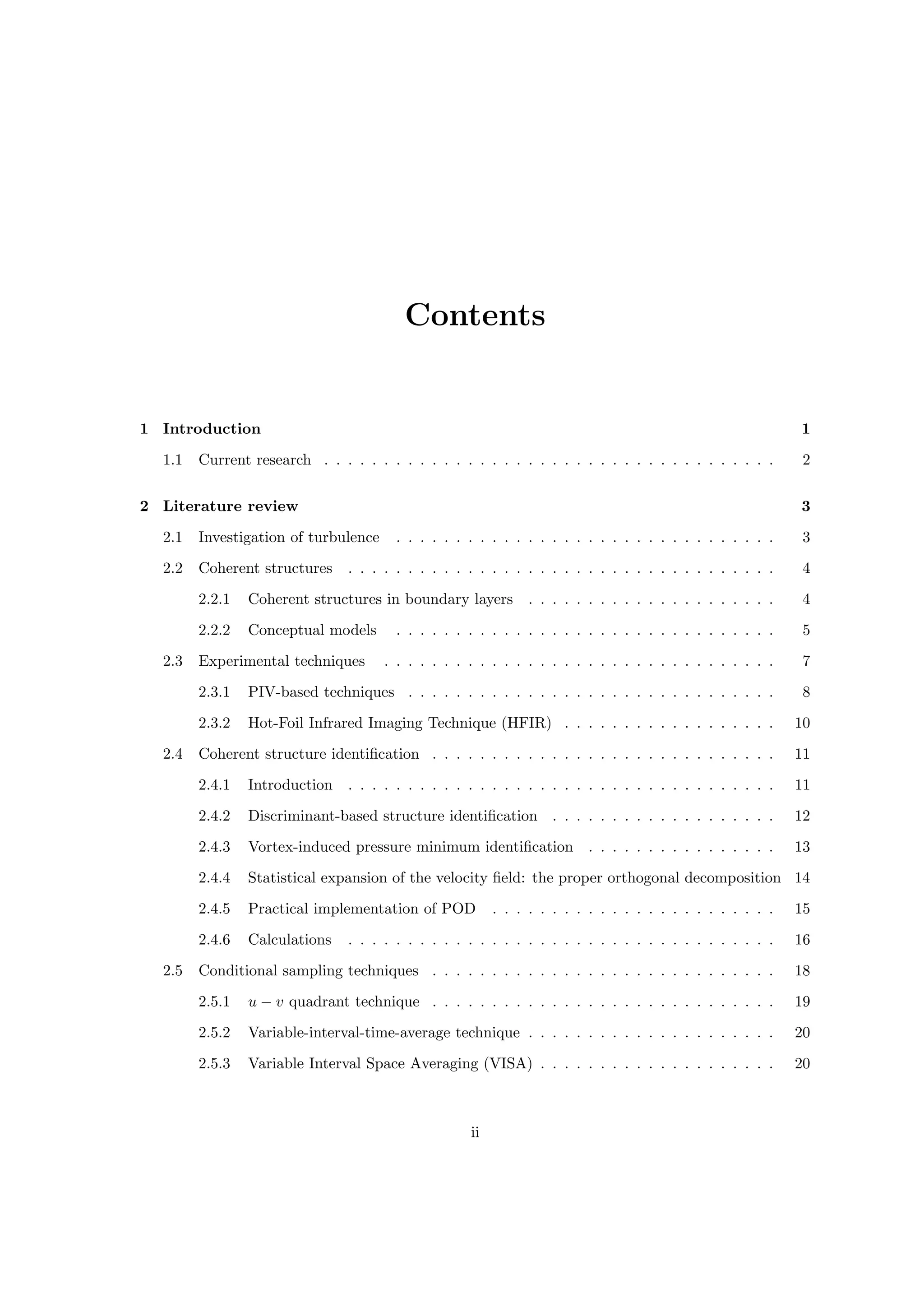

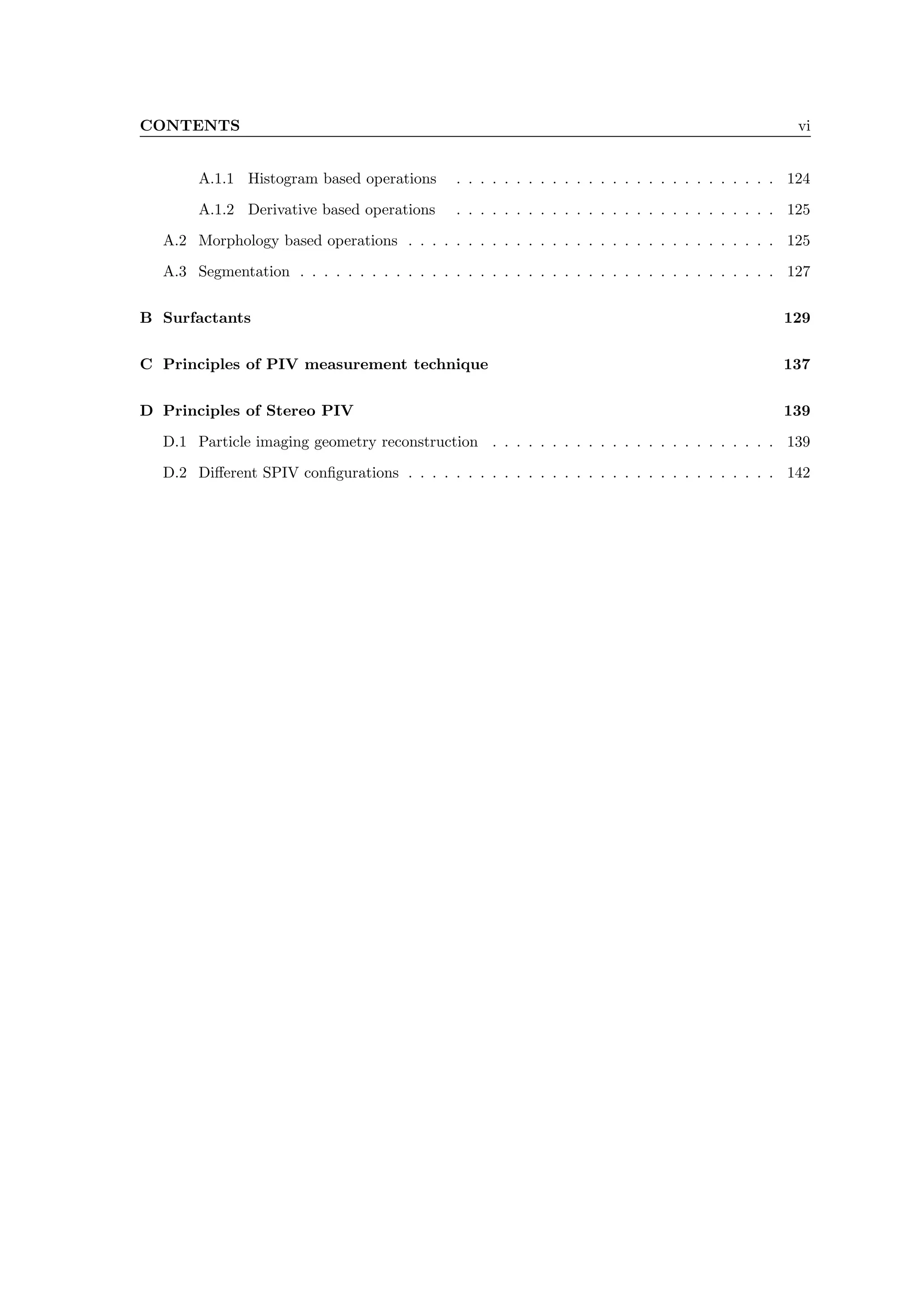

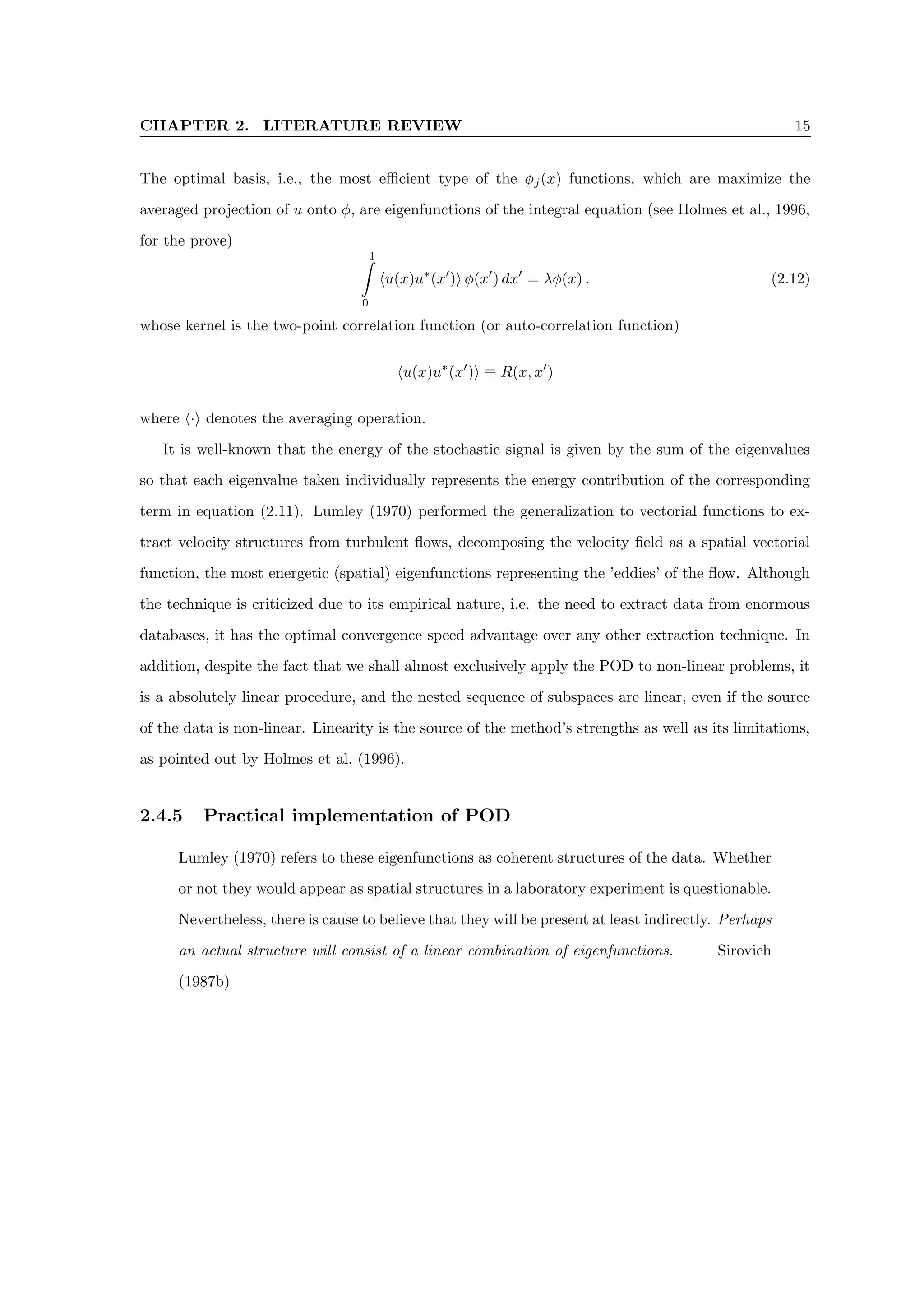

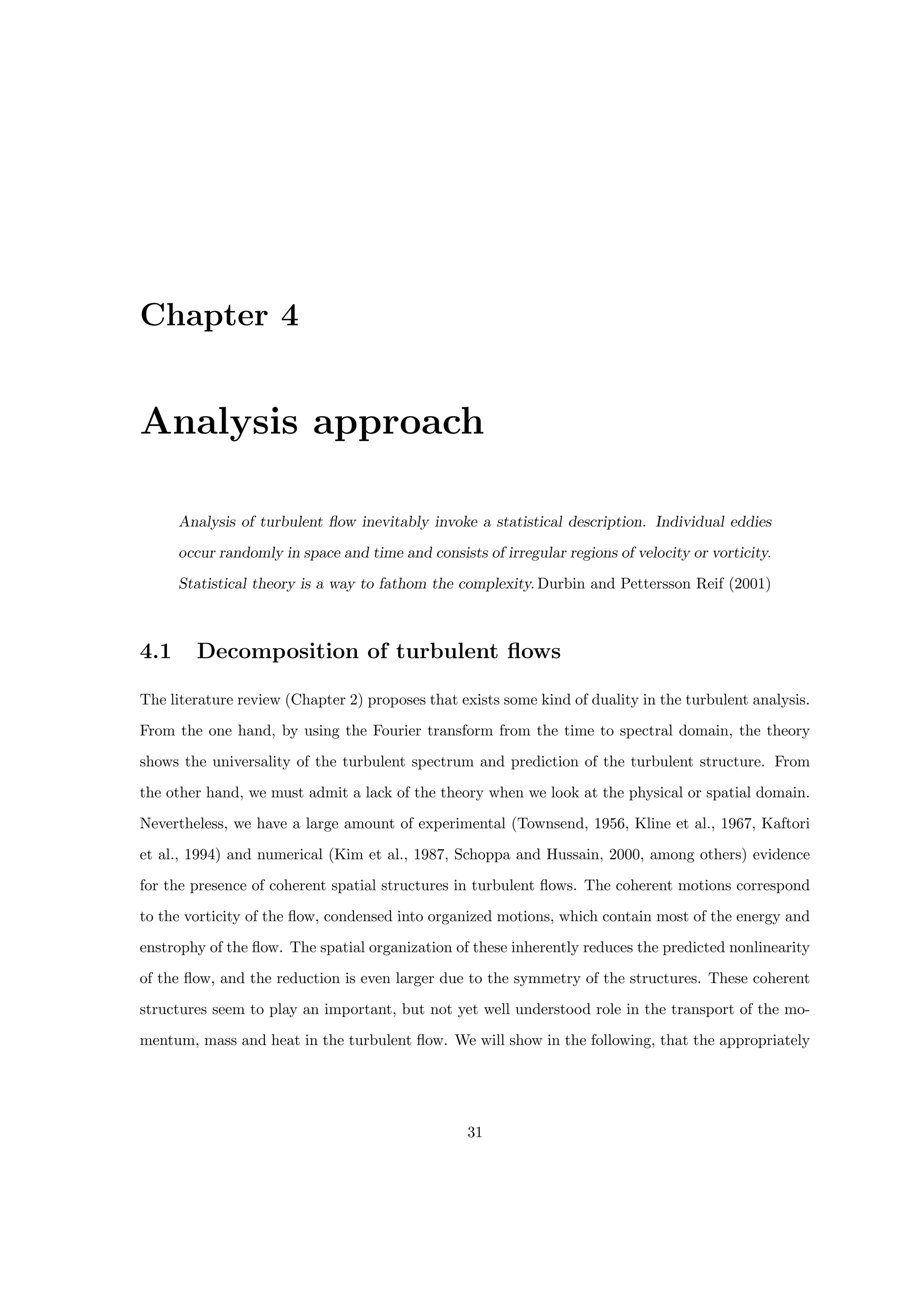

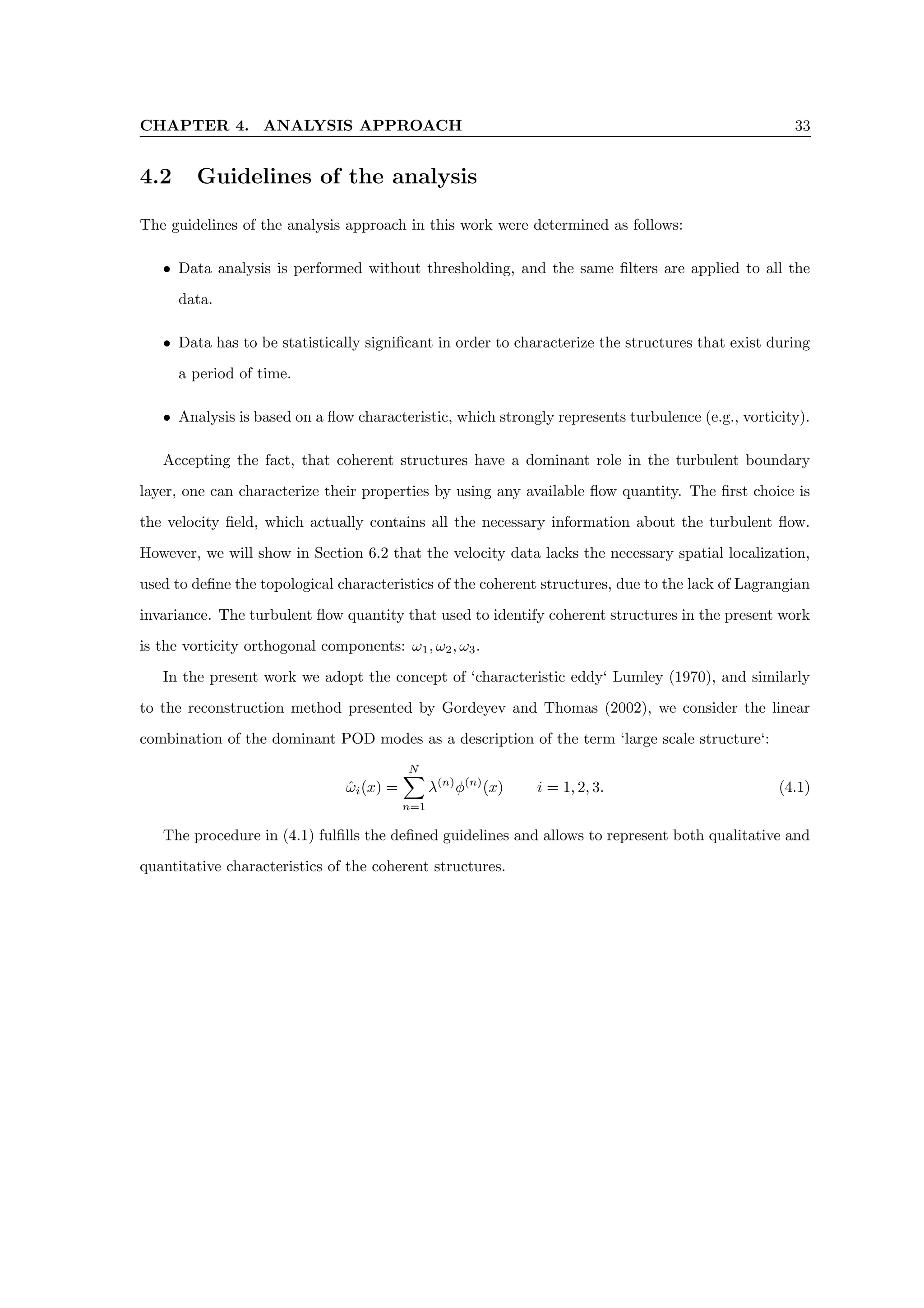

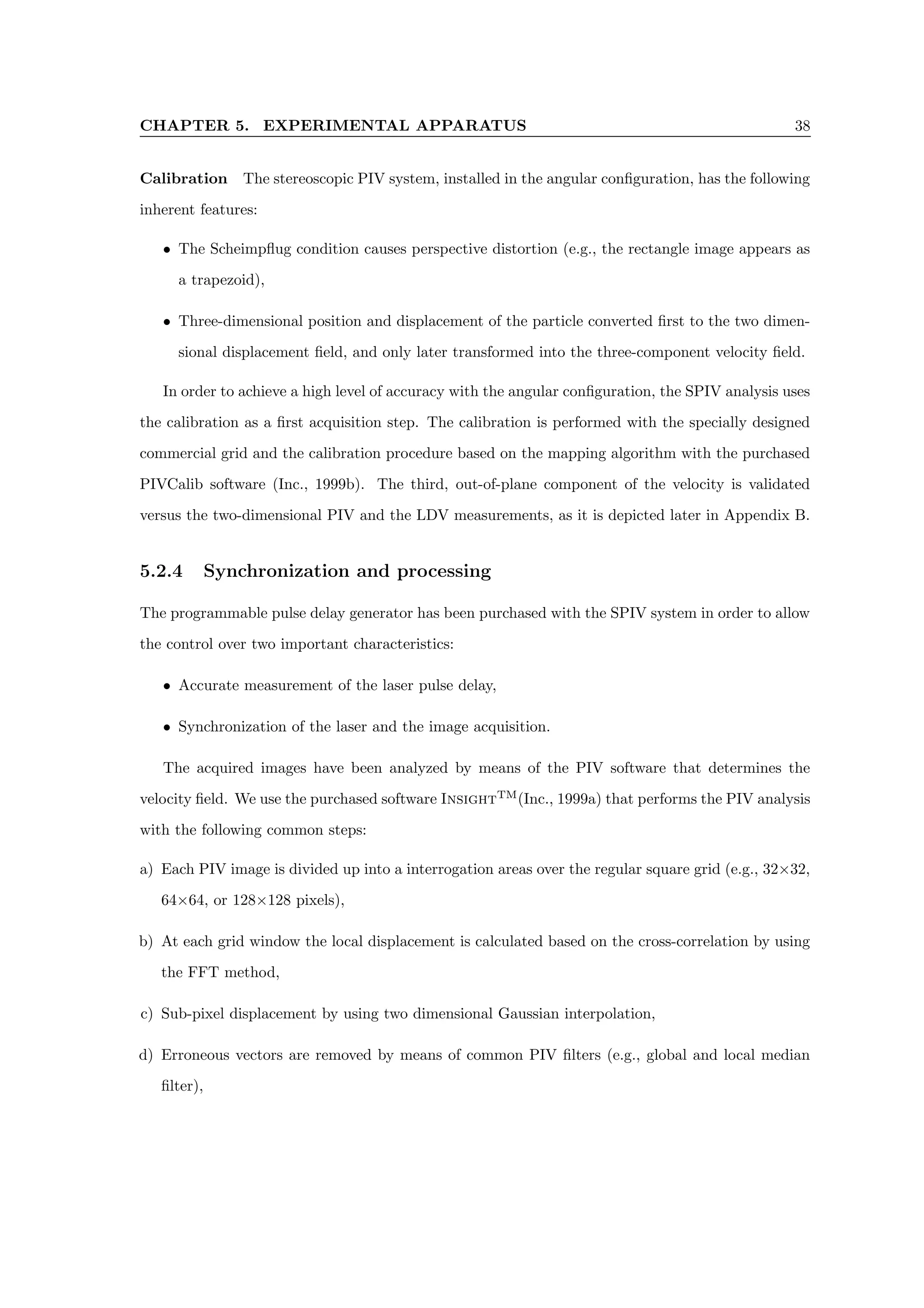

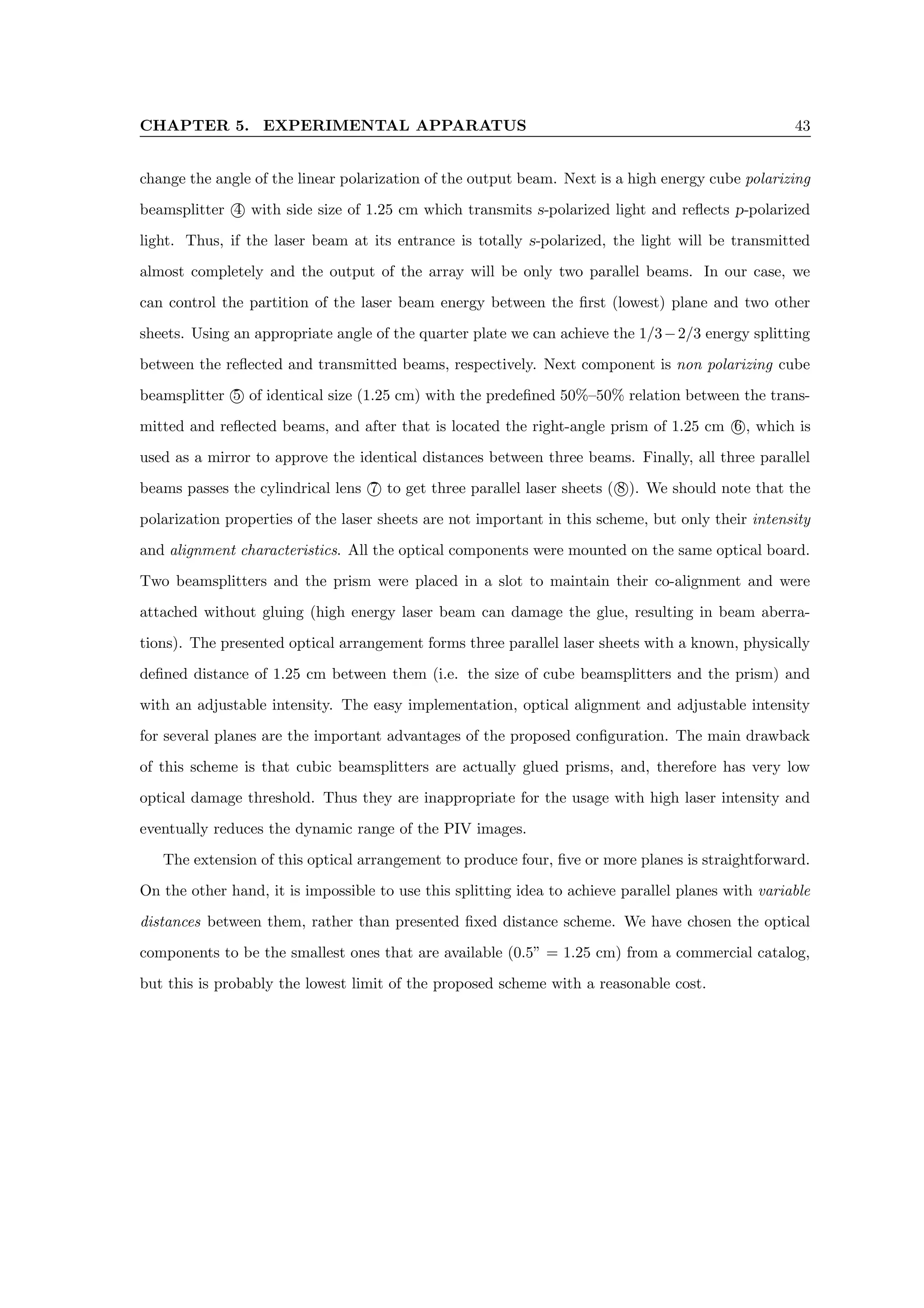

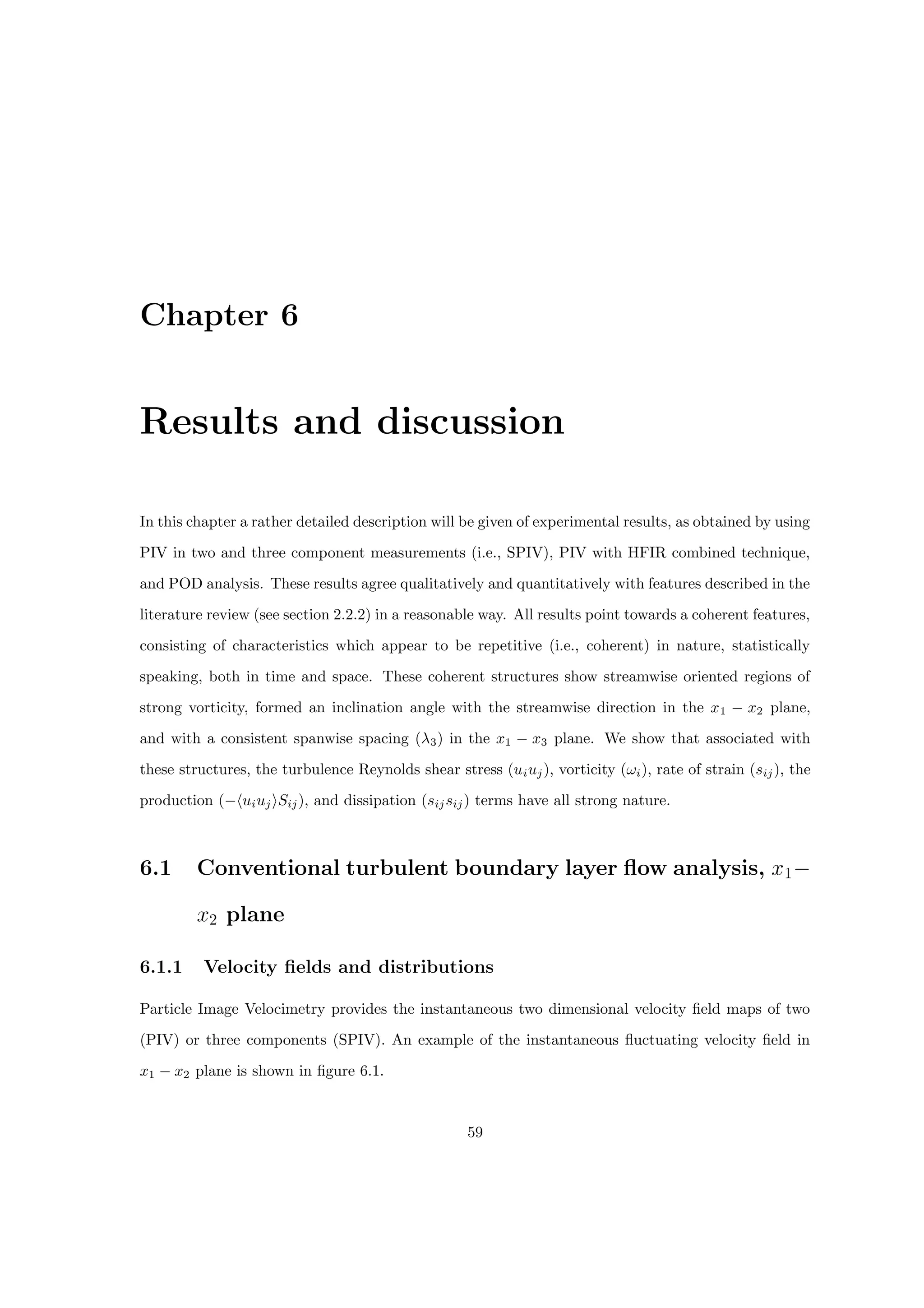

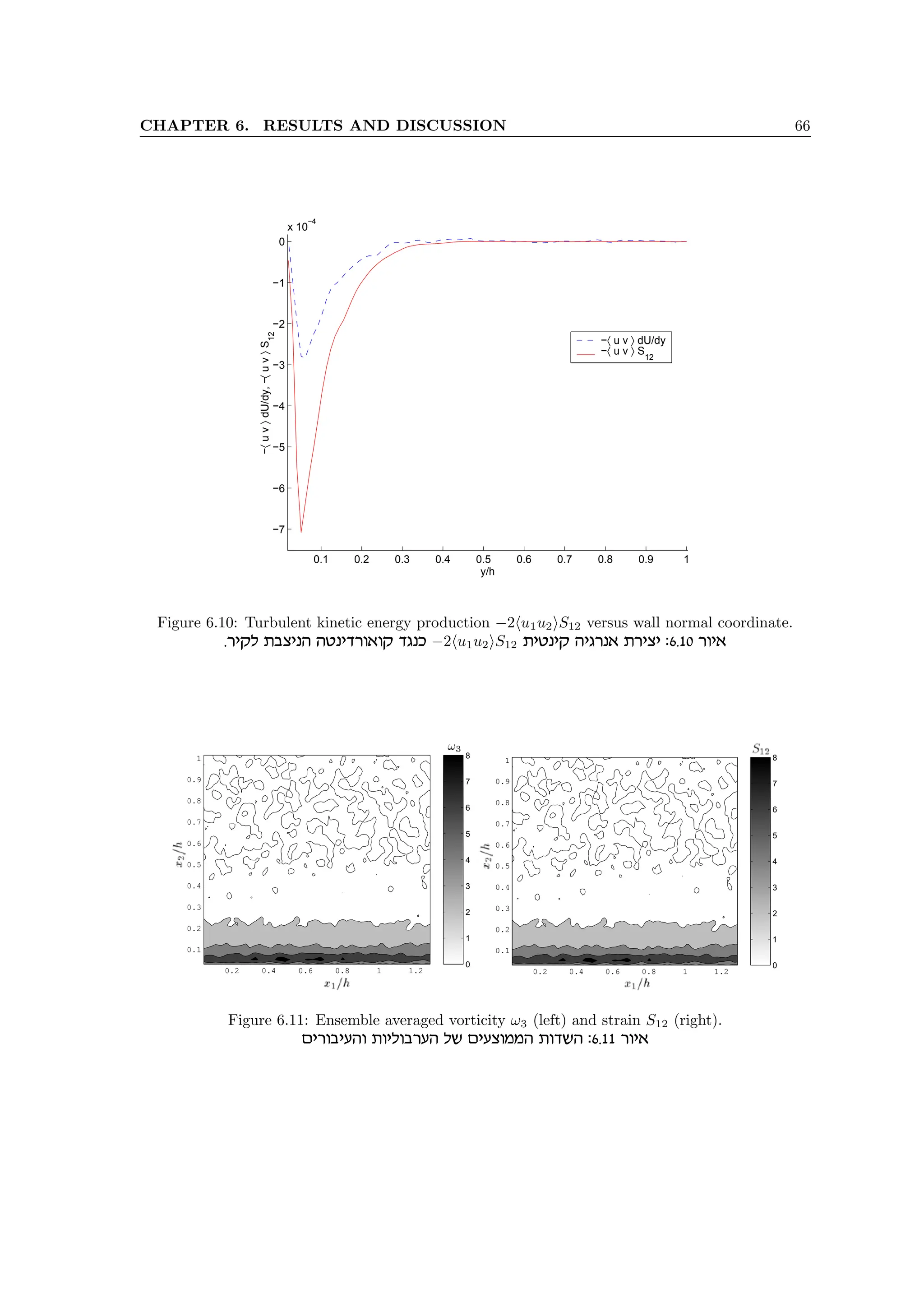

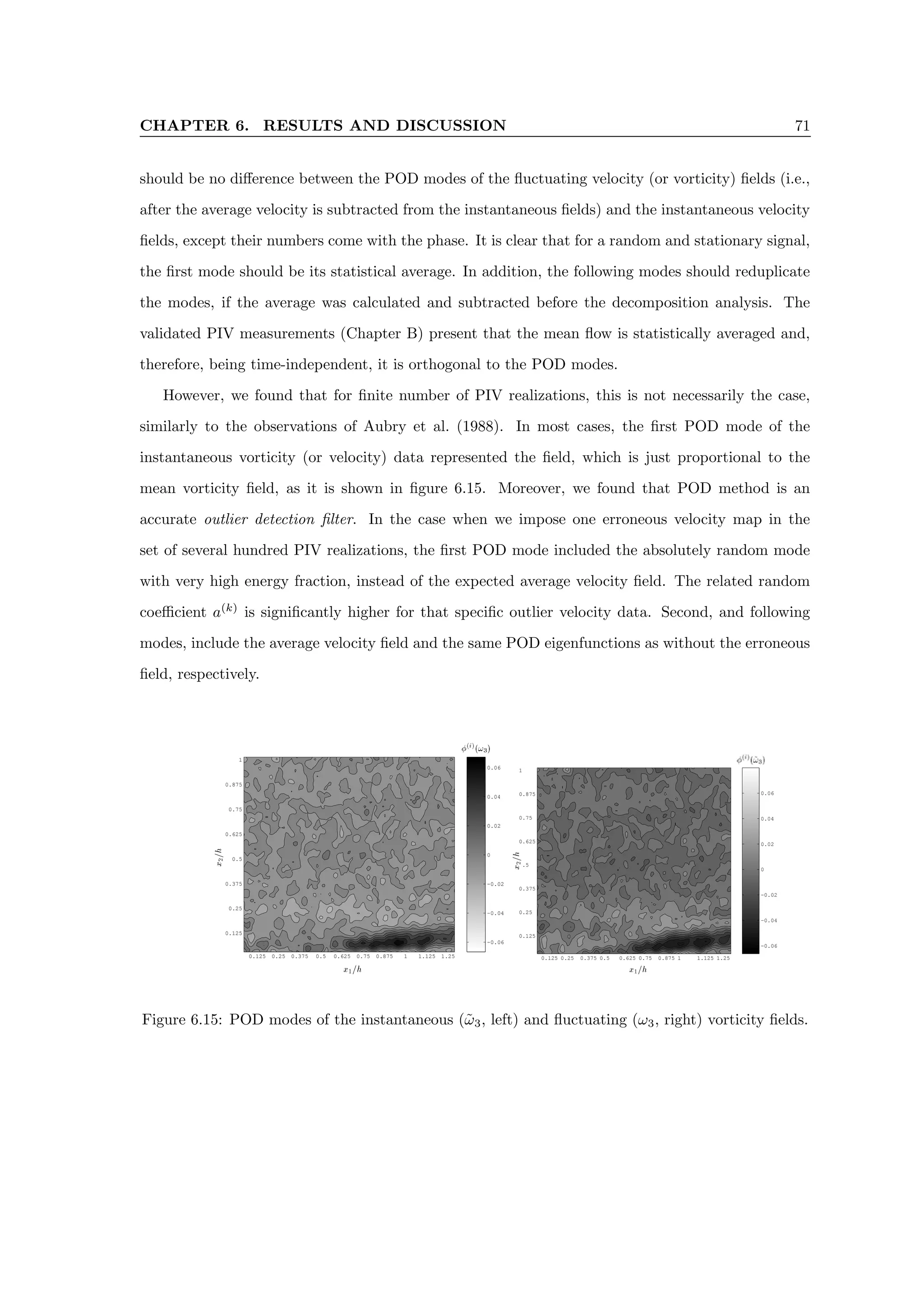

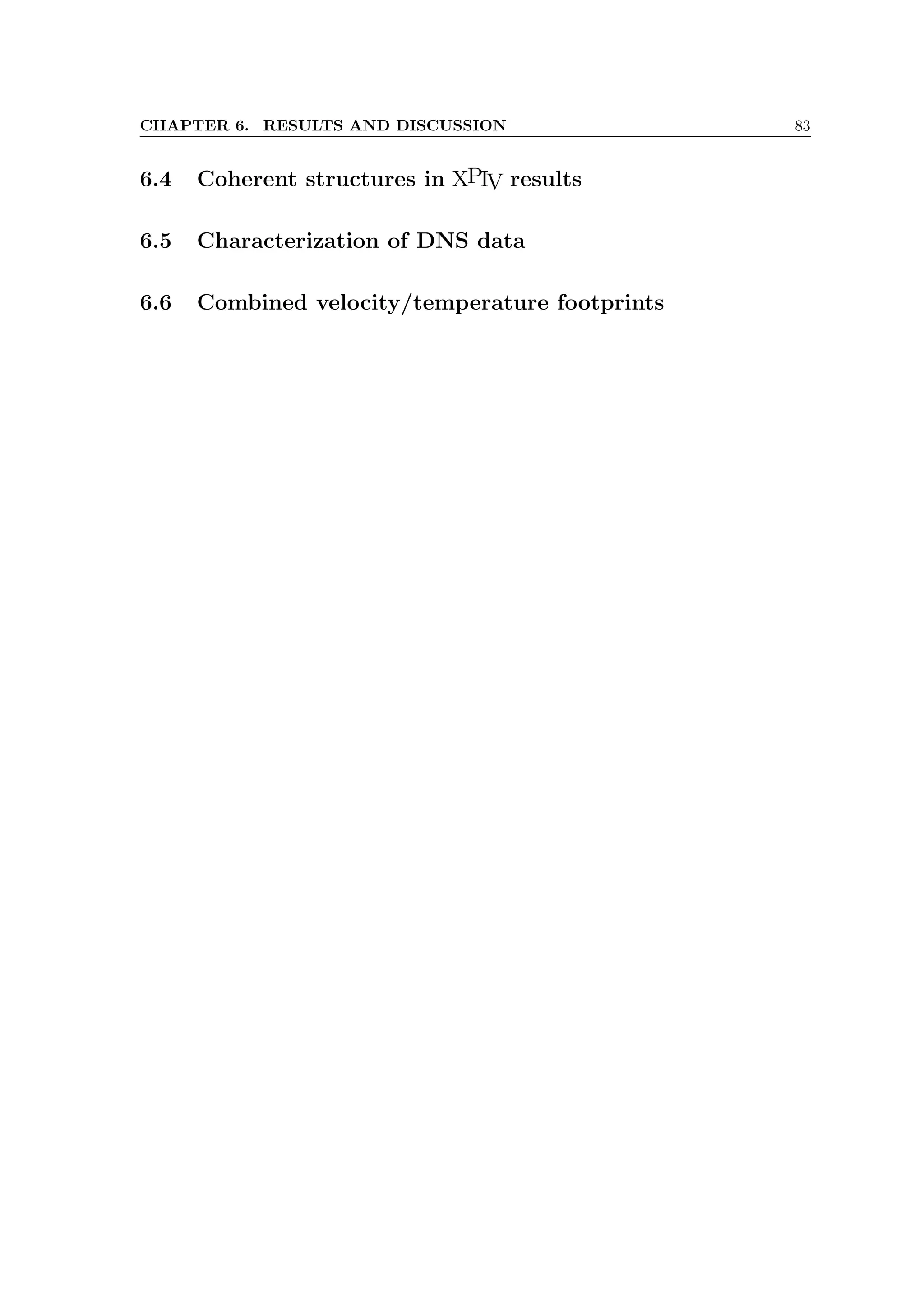

![CHAPTER 6. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 67

−10 −5 0 5 10 15 20

0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 0.07 0.08 0.09 0.1

0.002

0.007

0.012

0.017

0.022

x [m]

y

[m]

ωz

Figure 6.12: Instantaneous vorticity ω3 component field.

.zirbxd zeileaxrd dcy :6.12 xei‘

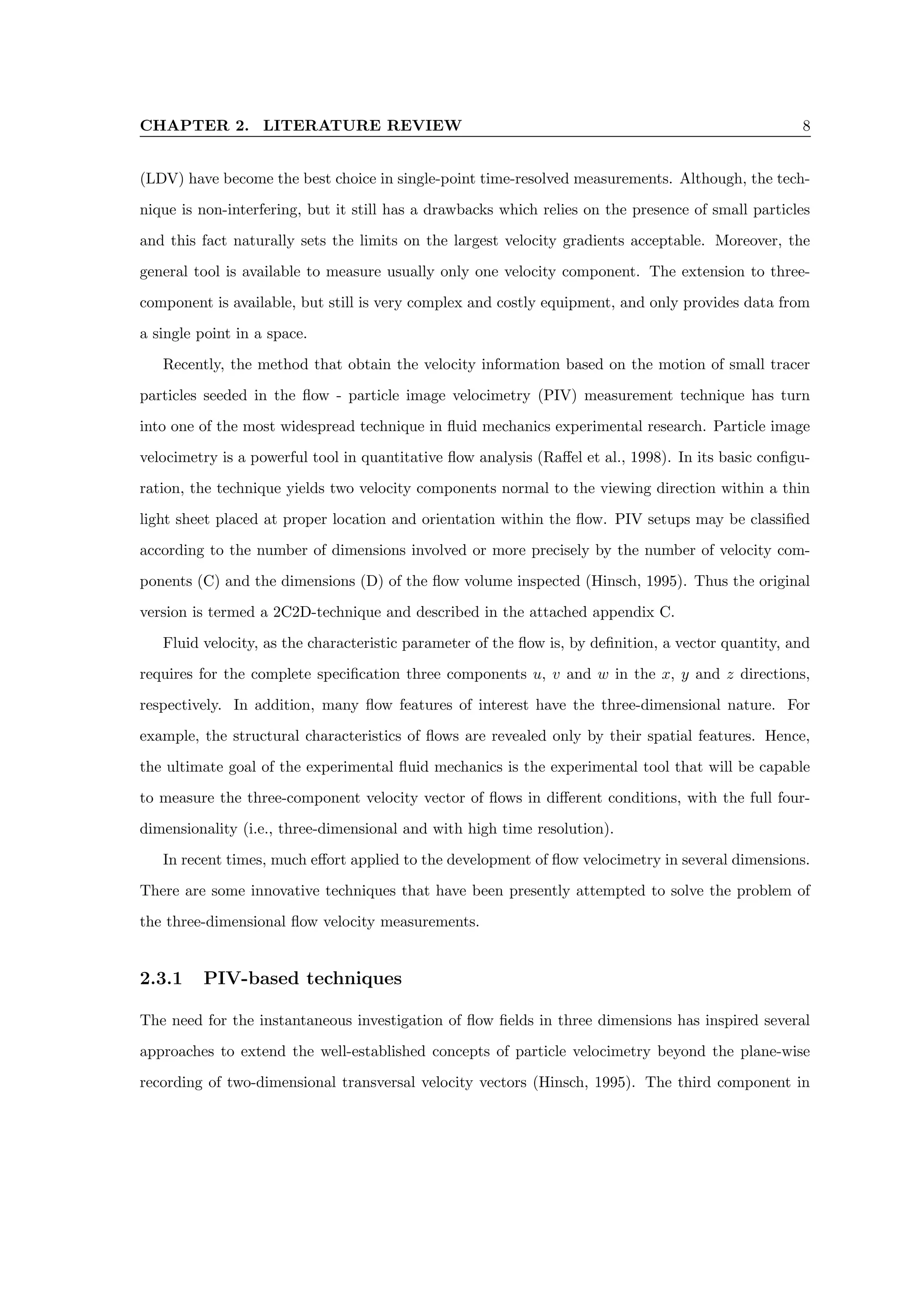

the connection to the turbulent energy production term −hu1u2iS12. Actually, this term represents

the rate at which the energy is transferred from mean flow to turbulent fluctuations. We already

noted that this term appears in the mean flow energy equation (3.16) and proposes that the turbulent

energy is generated from the mean shear. In addition, we present in the following analysis that the

strong mean vorticity (or strain) performs a masking effect on the concealed coherent structure of

the boundary layer. When we look at the instantaneous vorticity fields near the bottom wall, as one

presented in the figure 6.12, we can detect a large region of the concentrated vorticity, elongated in

the streamwise direction and inclined at some small angle (i.e., between 5◦

and 15◦

). Such structures

appear randomly in measured fields and at different streamwise locations, relatively to the measured

flow field boundaries.

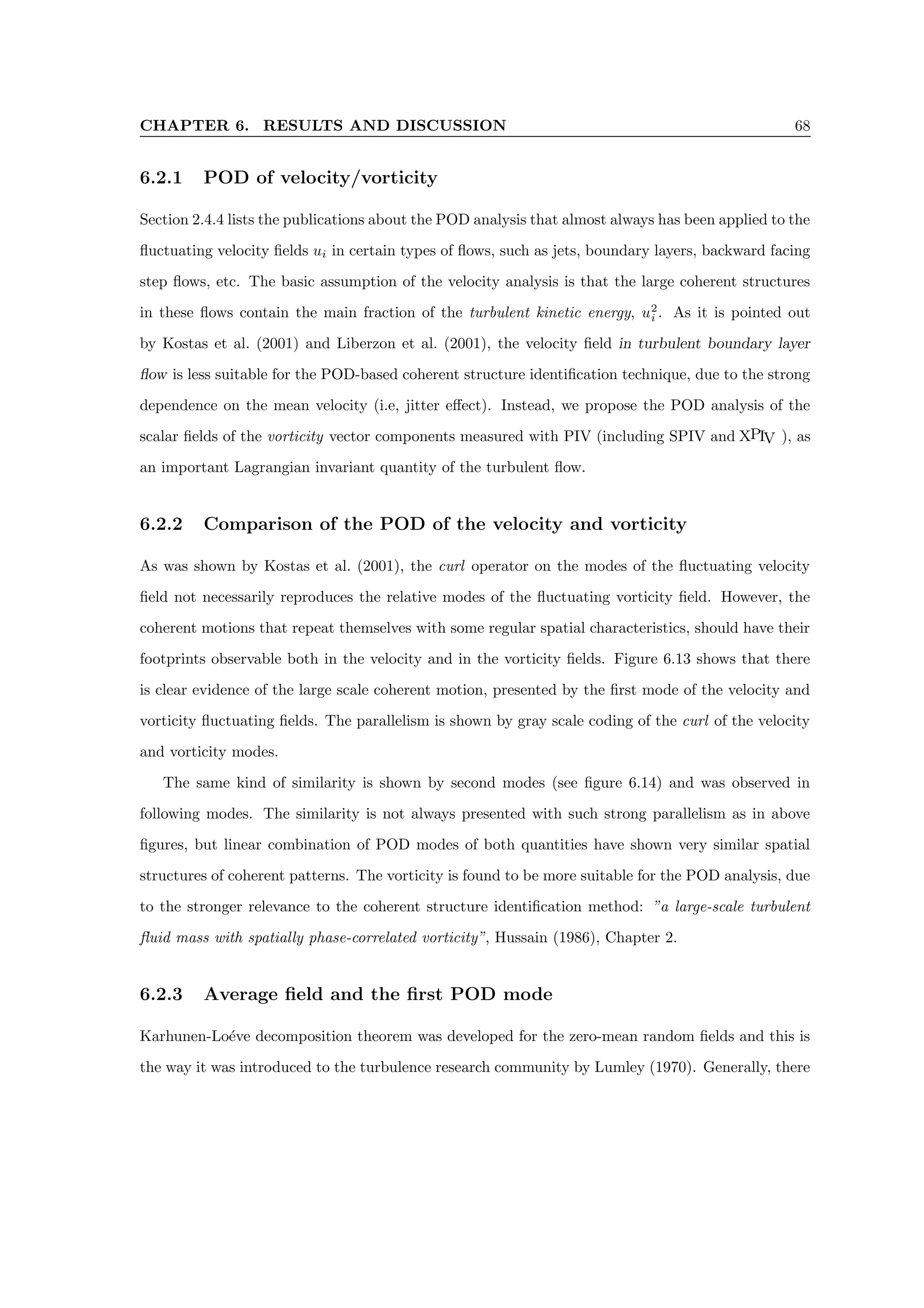

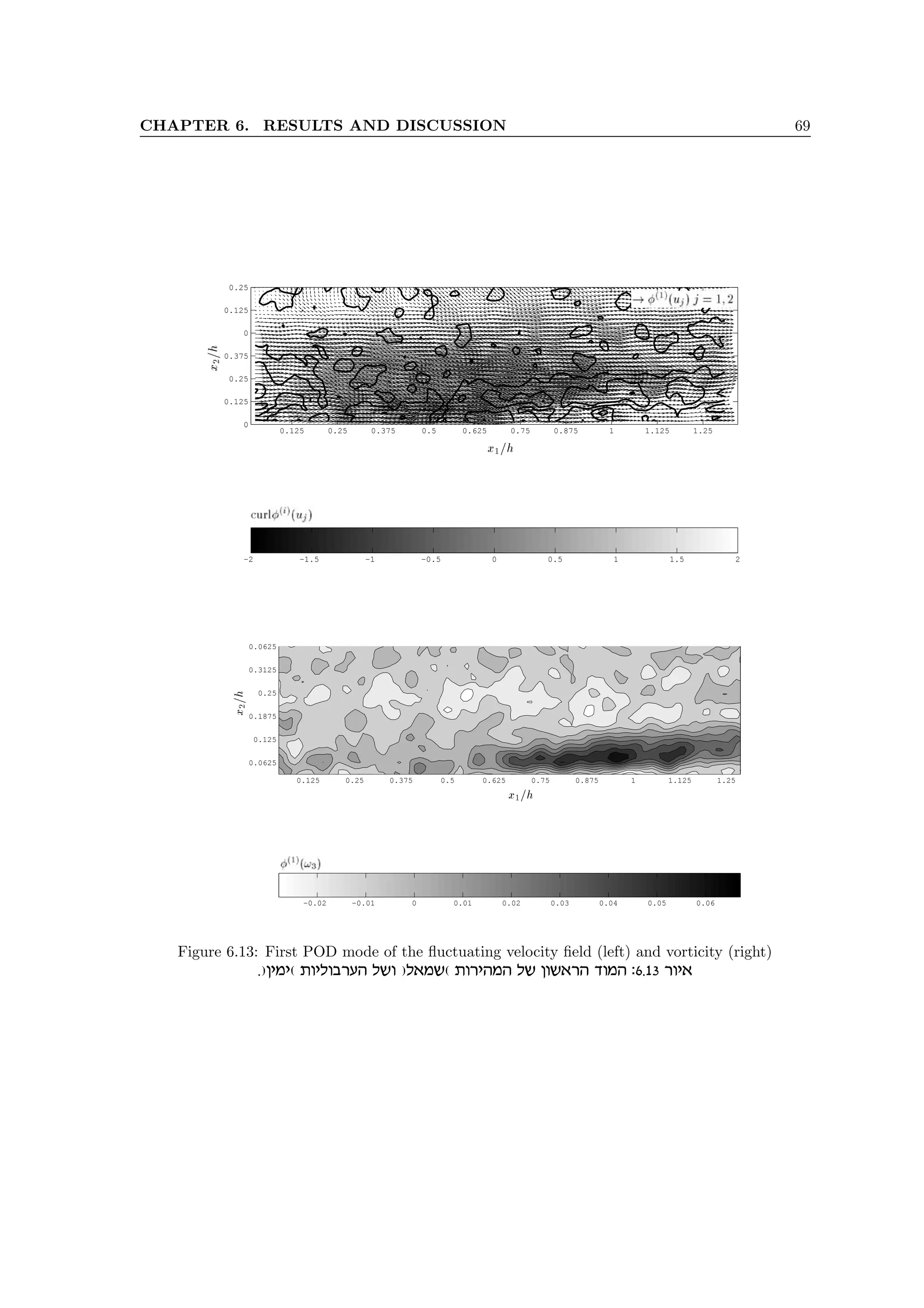

6.2 Linear combination of the POD modes

The largest eddies do have directional preferences, and their shapes are characteristic of

the particular mean flow. The recognizable eddies are called ’coherent structures’. The

allusion is to human ability to recognize the forms, rather than to statistical concepts of

coherence. Durbin and Pettersson Reif (2001)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-79-2048.jpg)

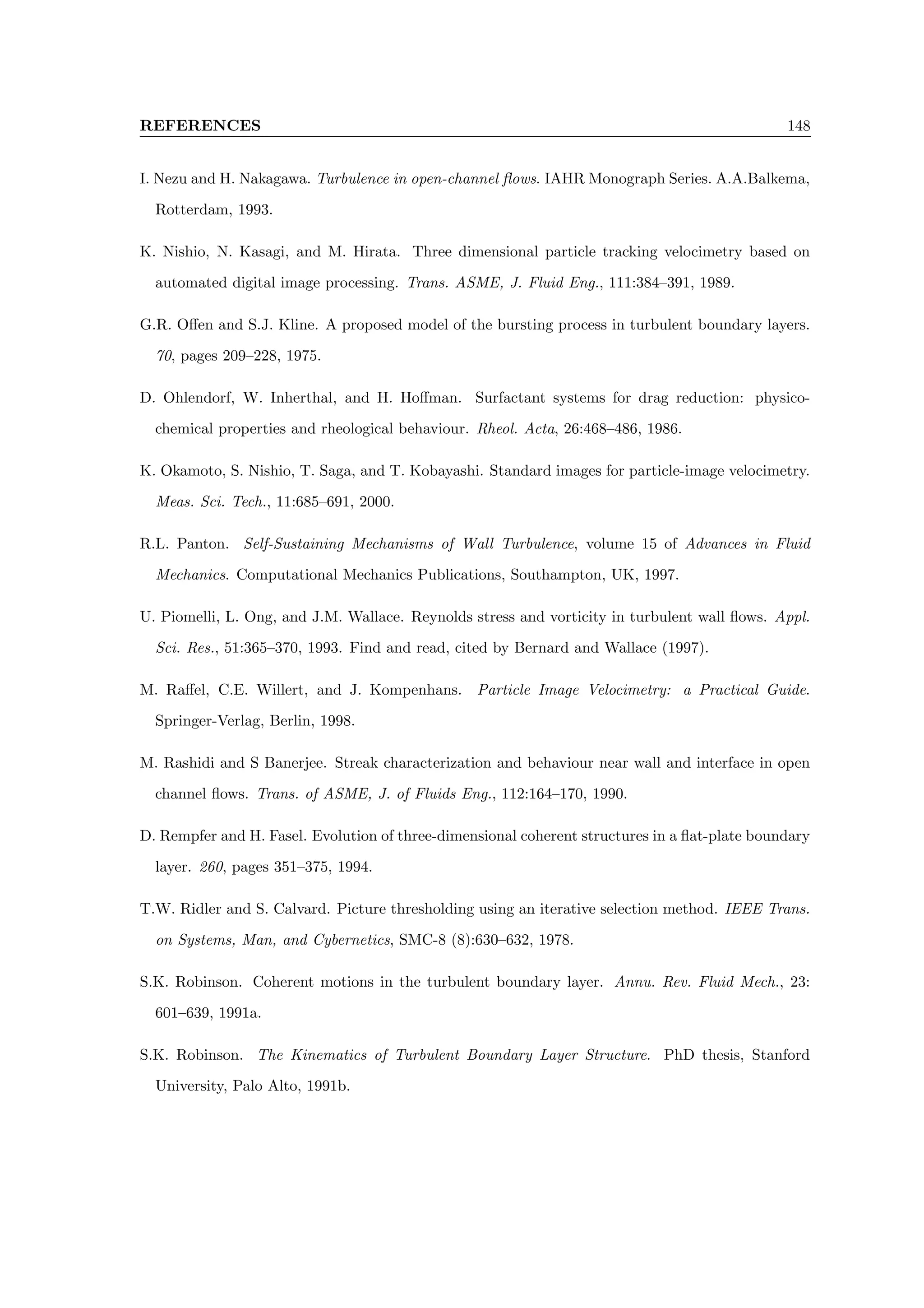

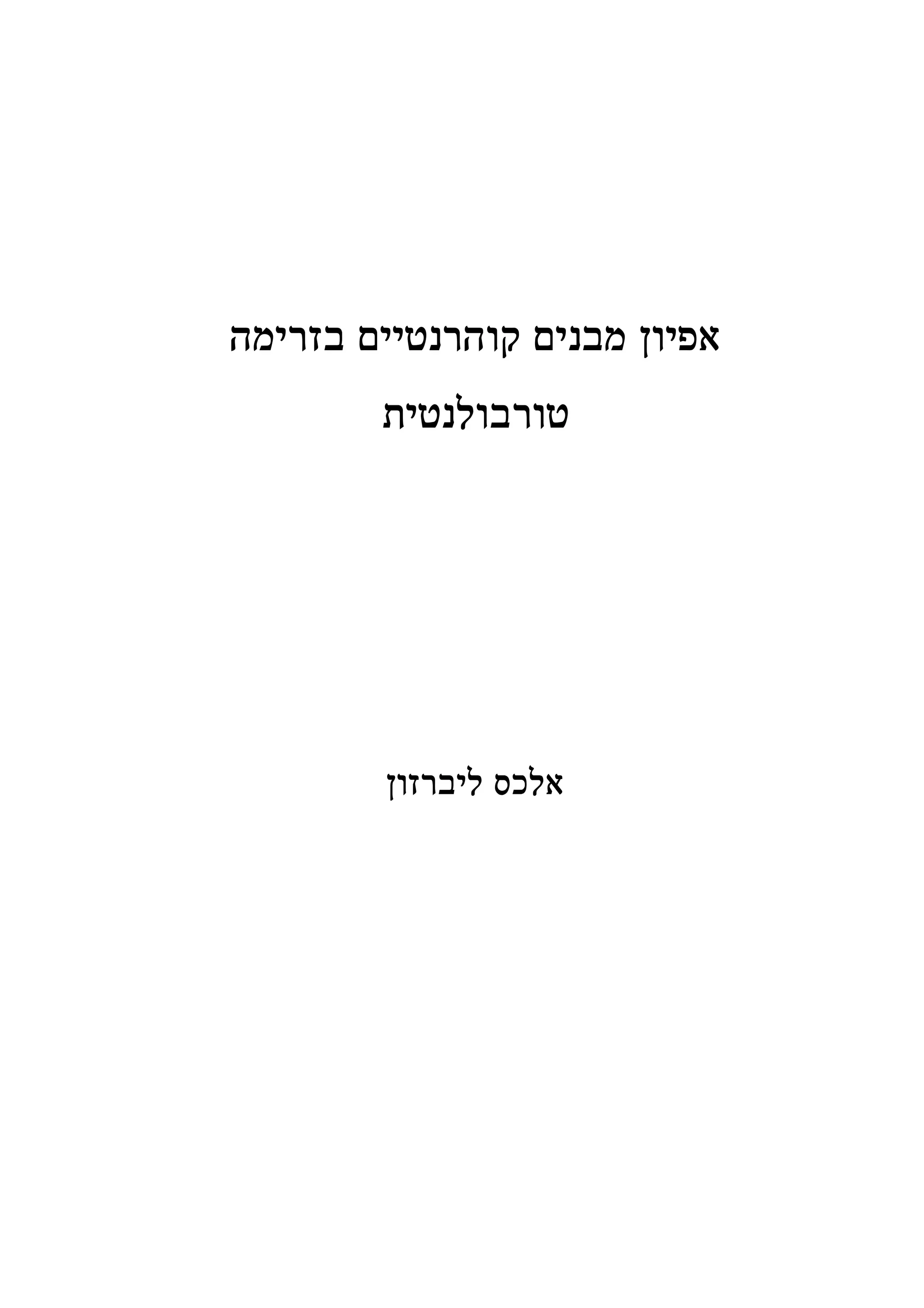

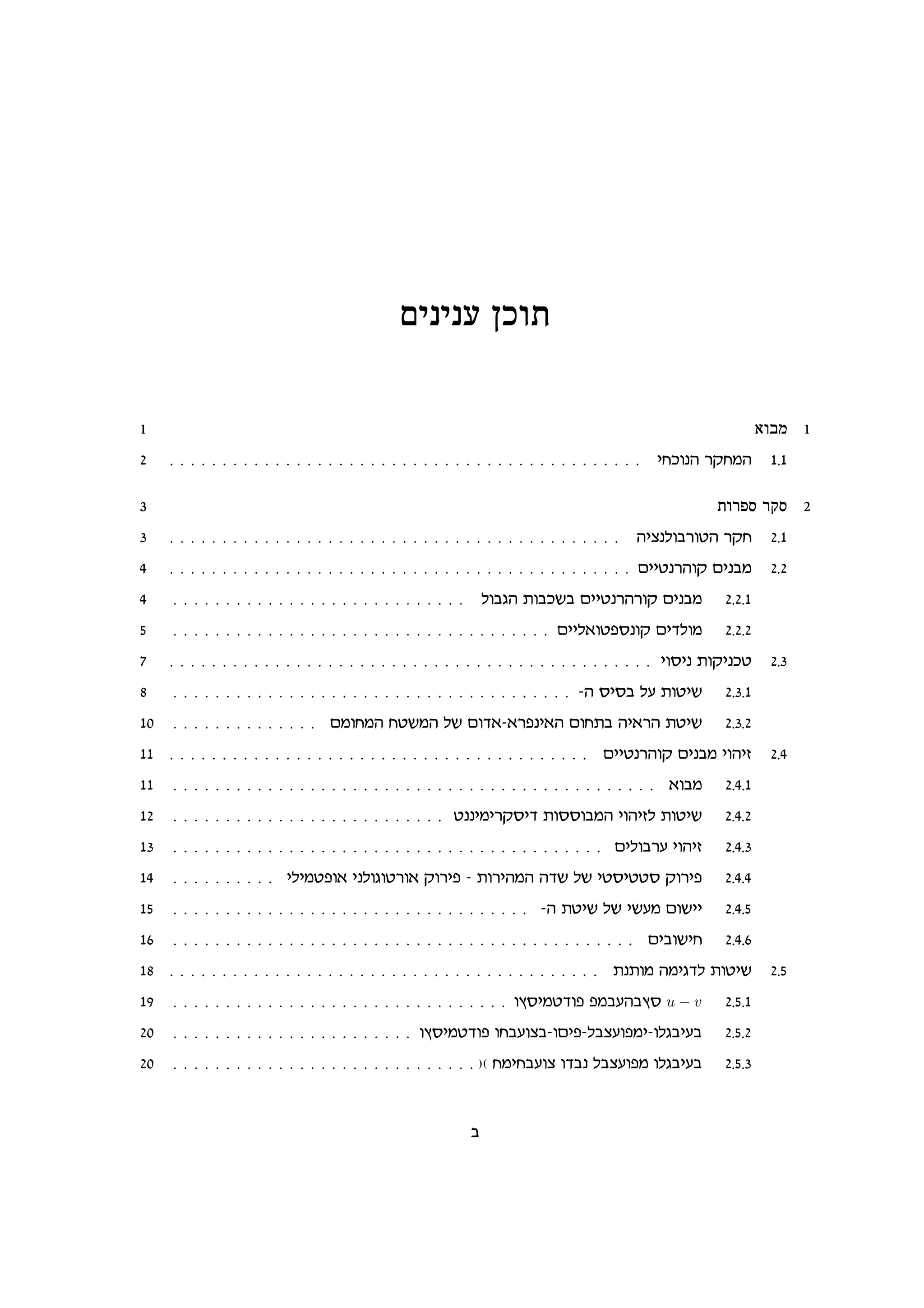

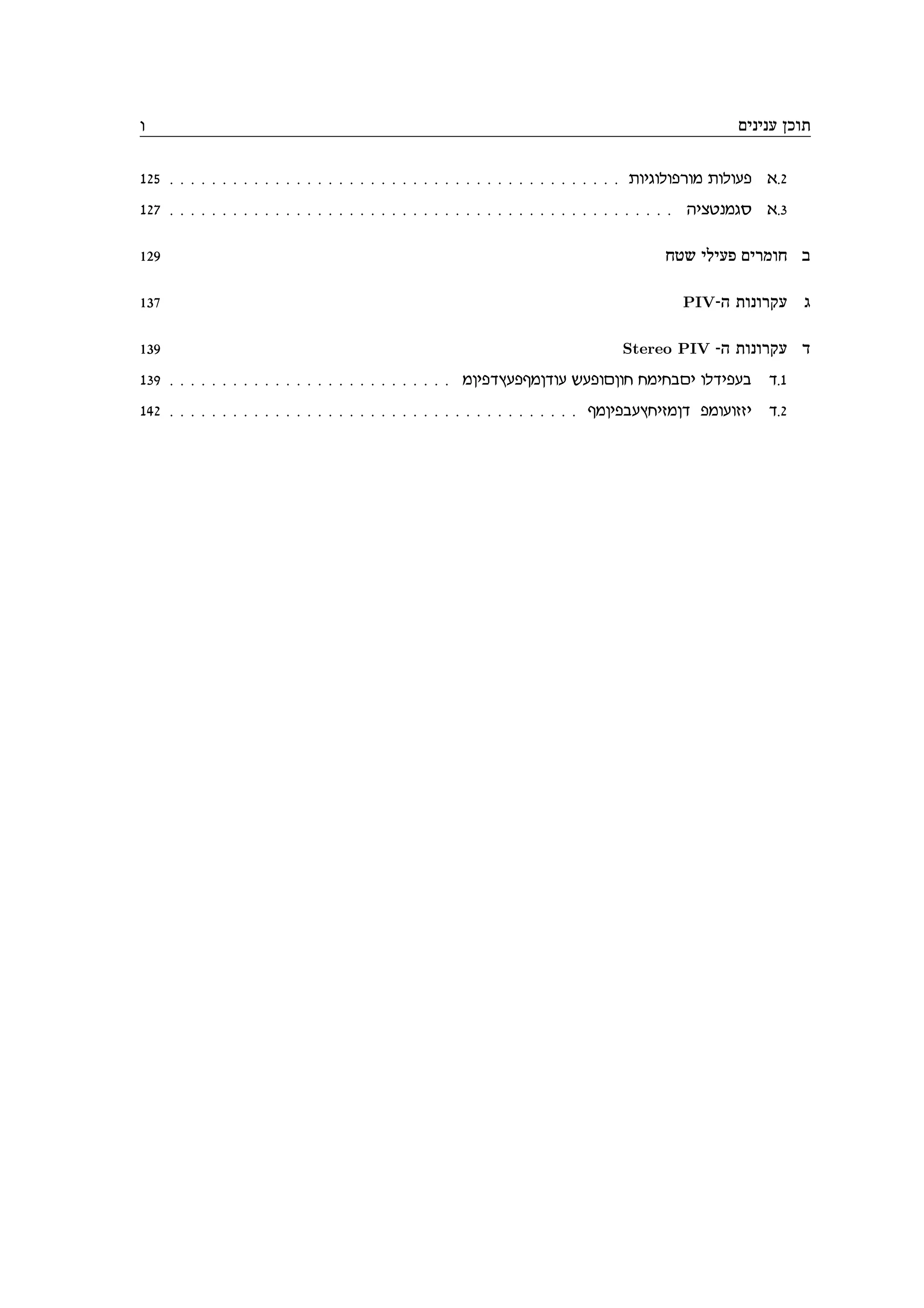

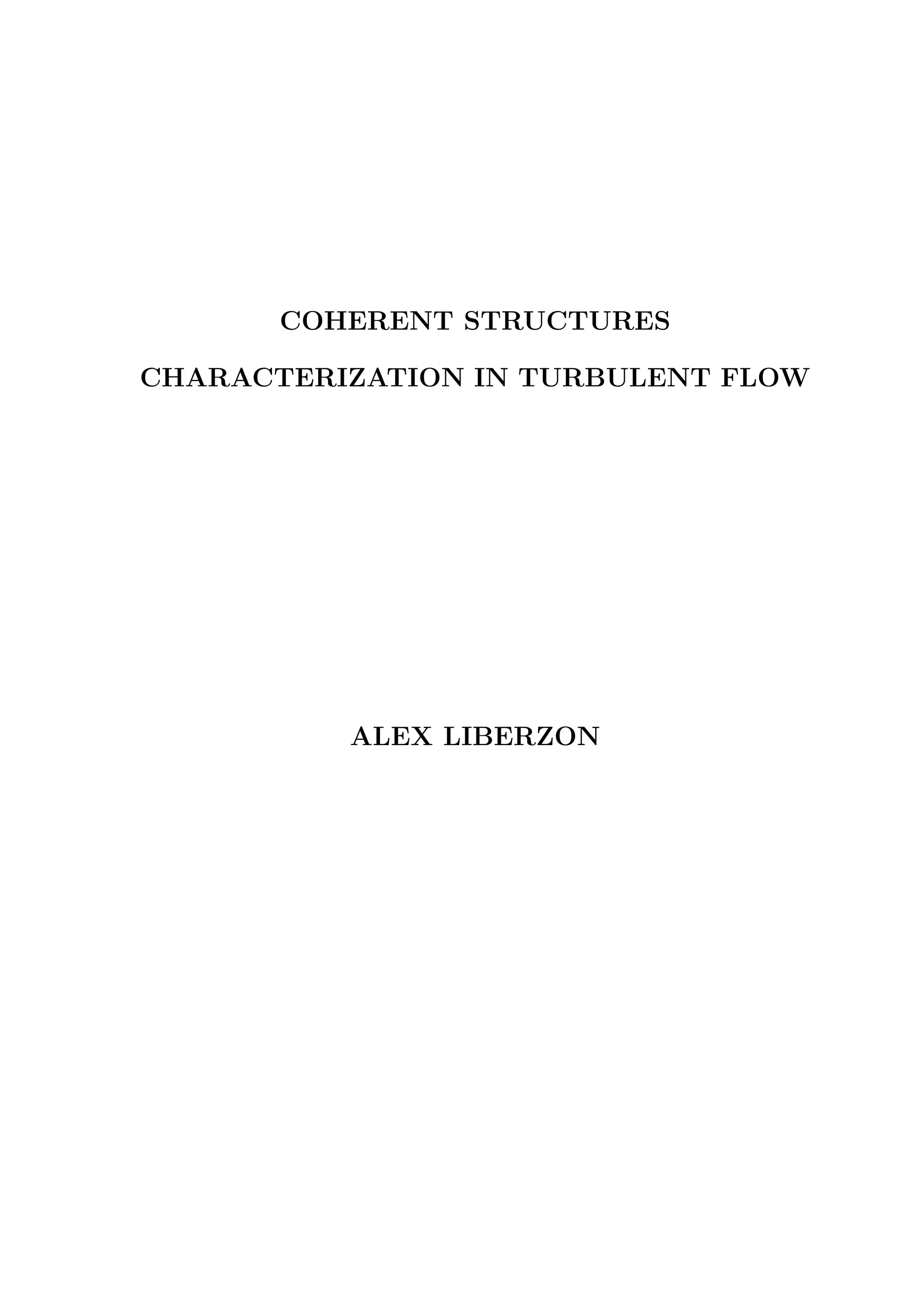

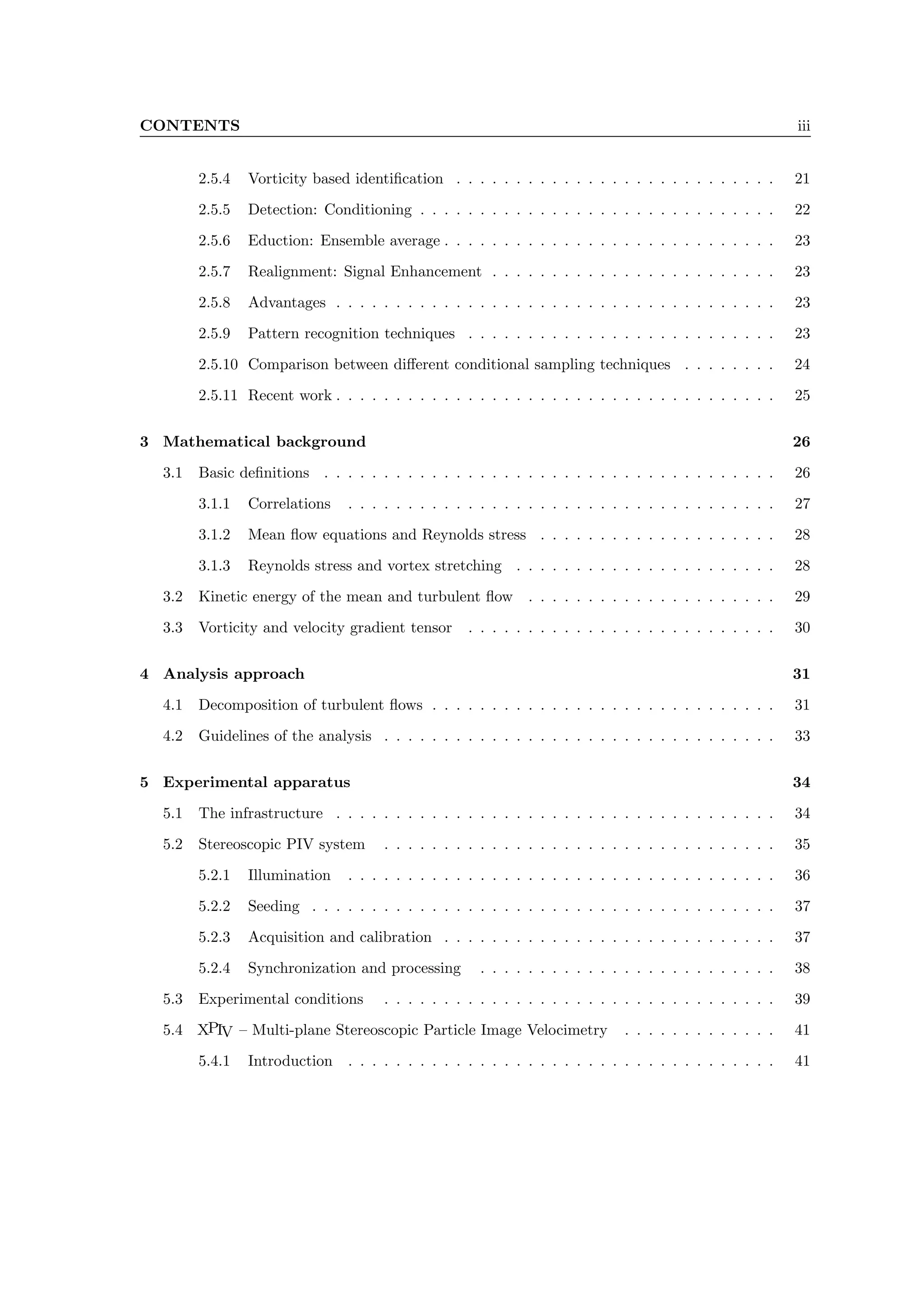

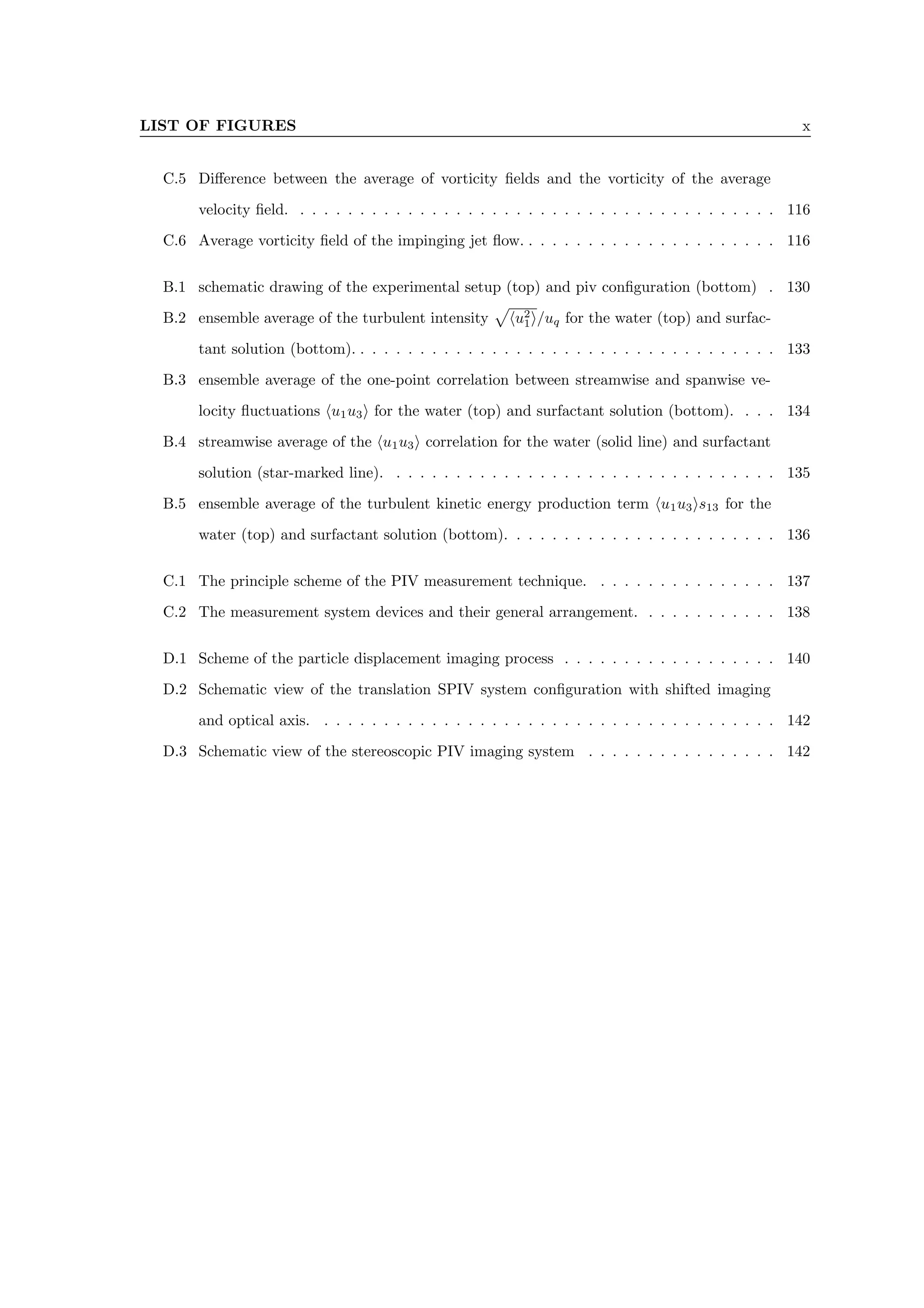

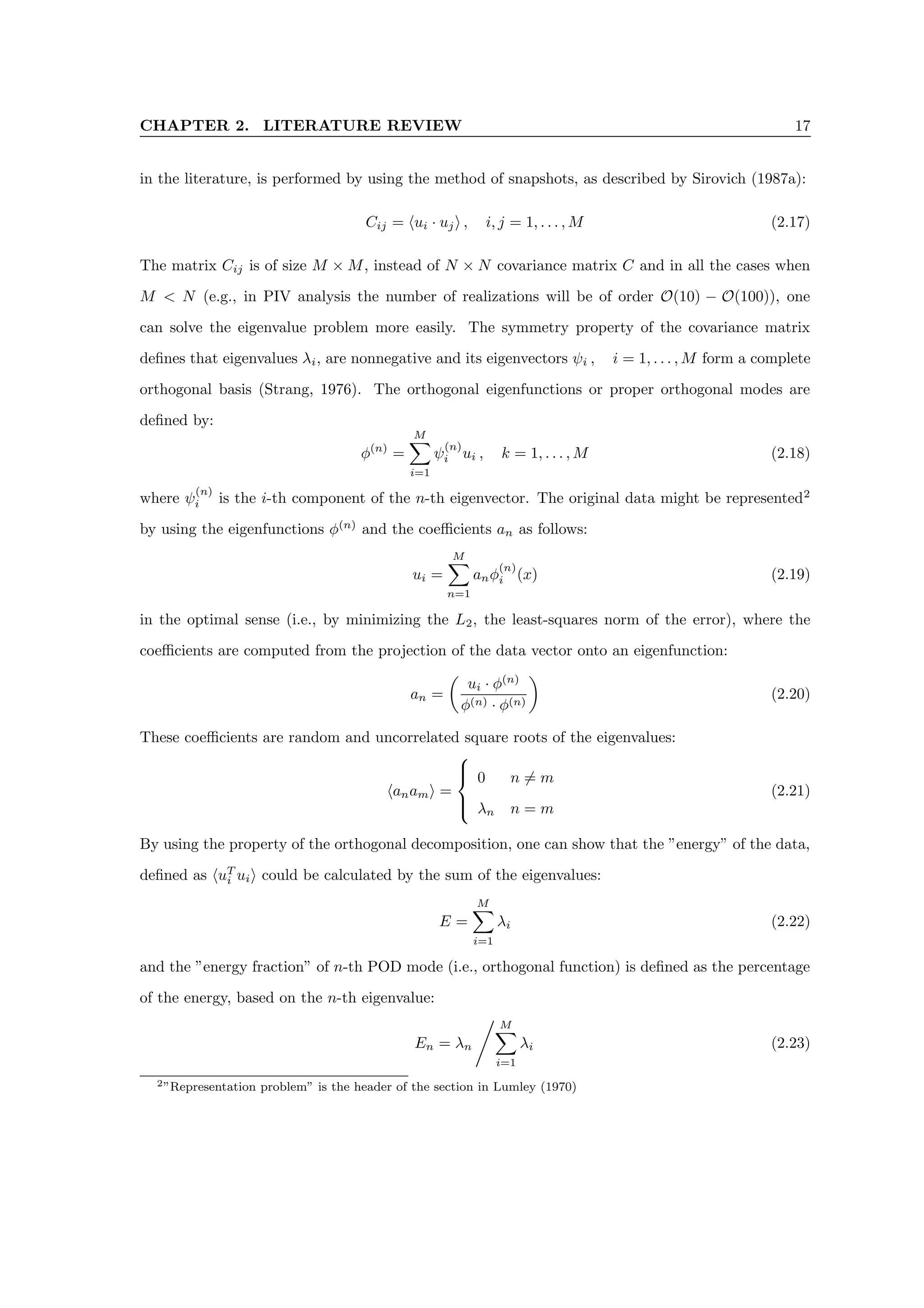

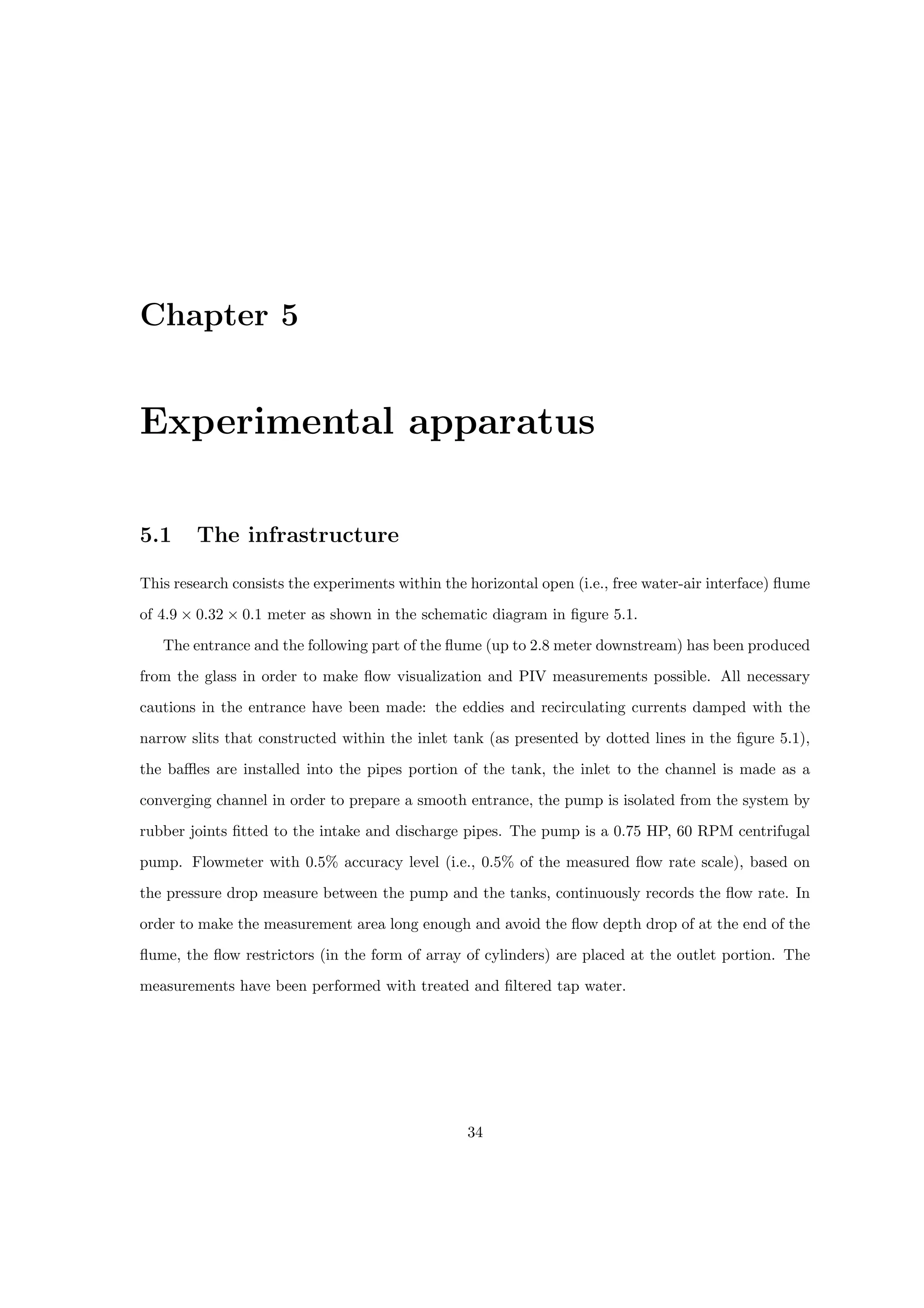

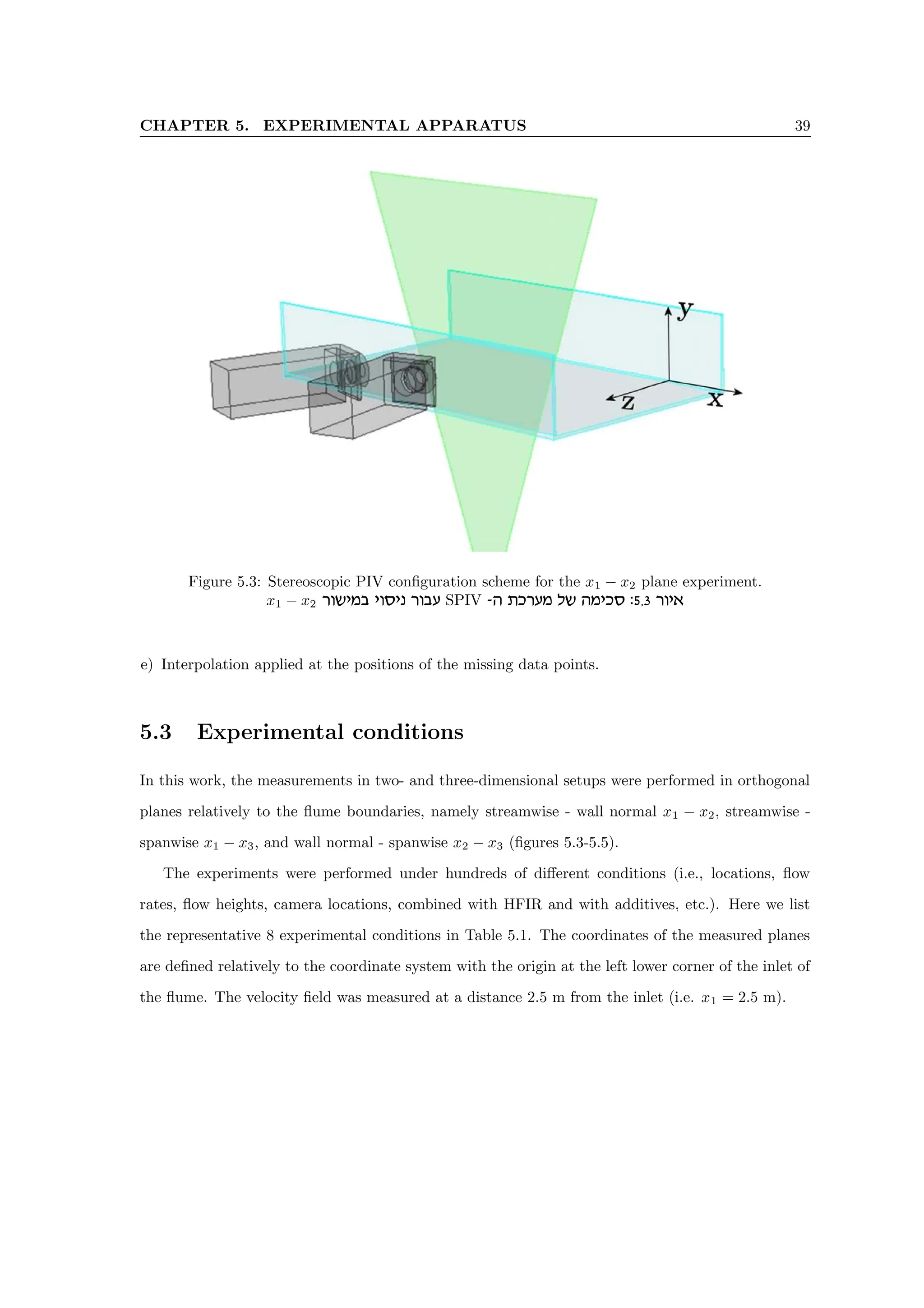

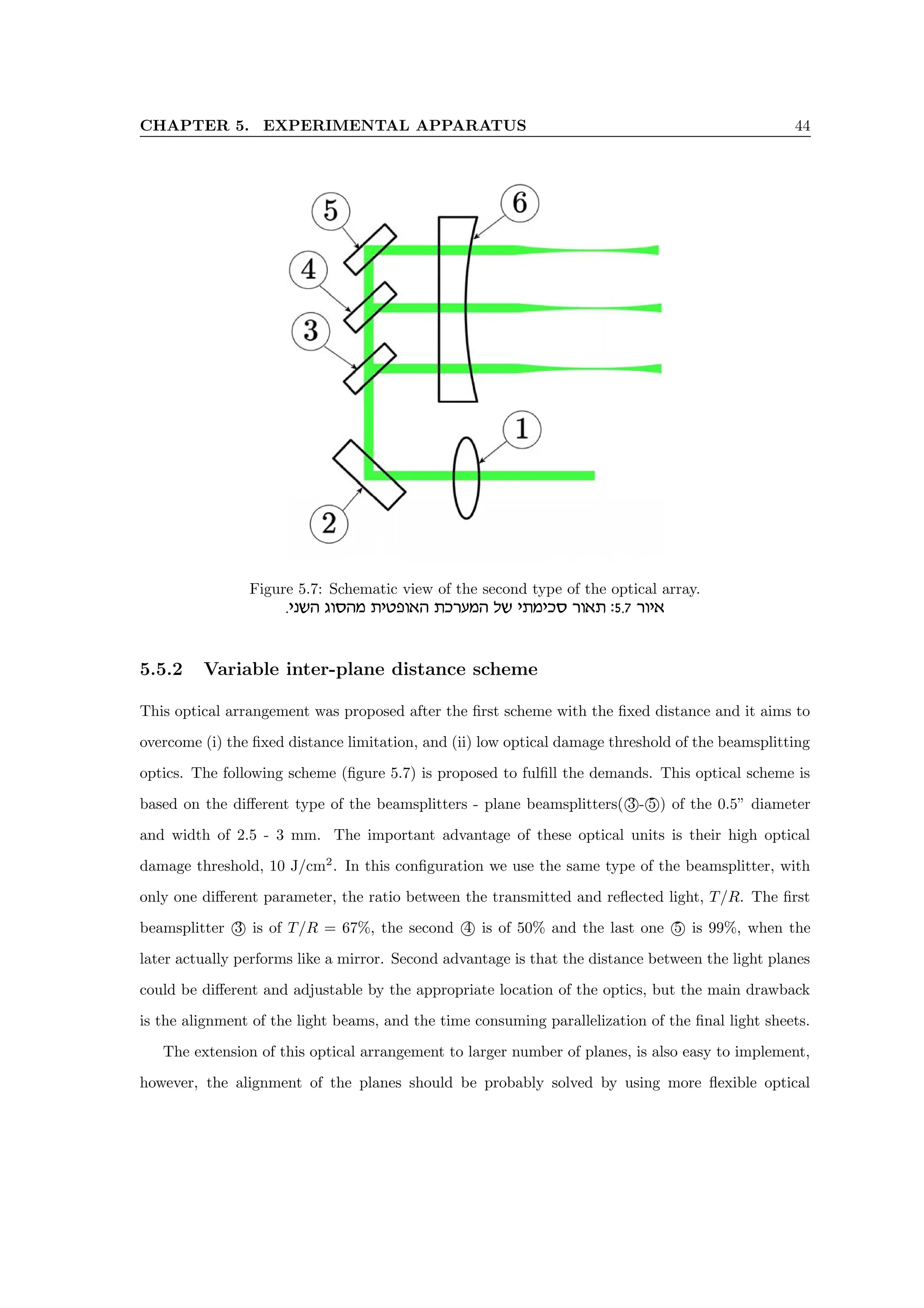

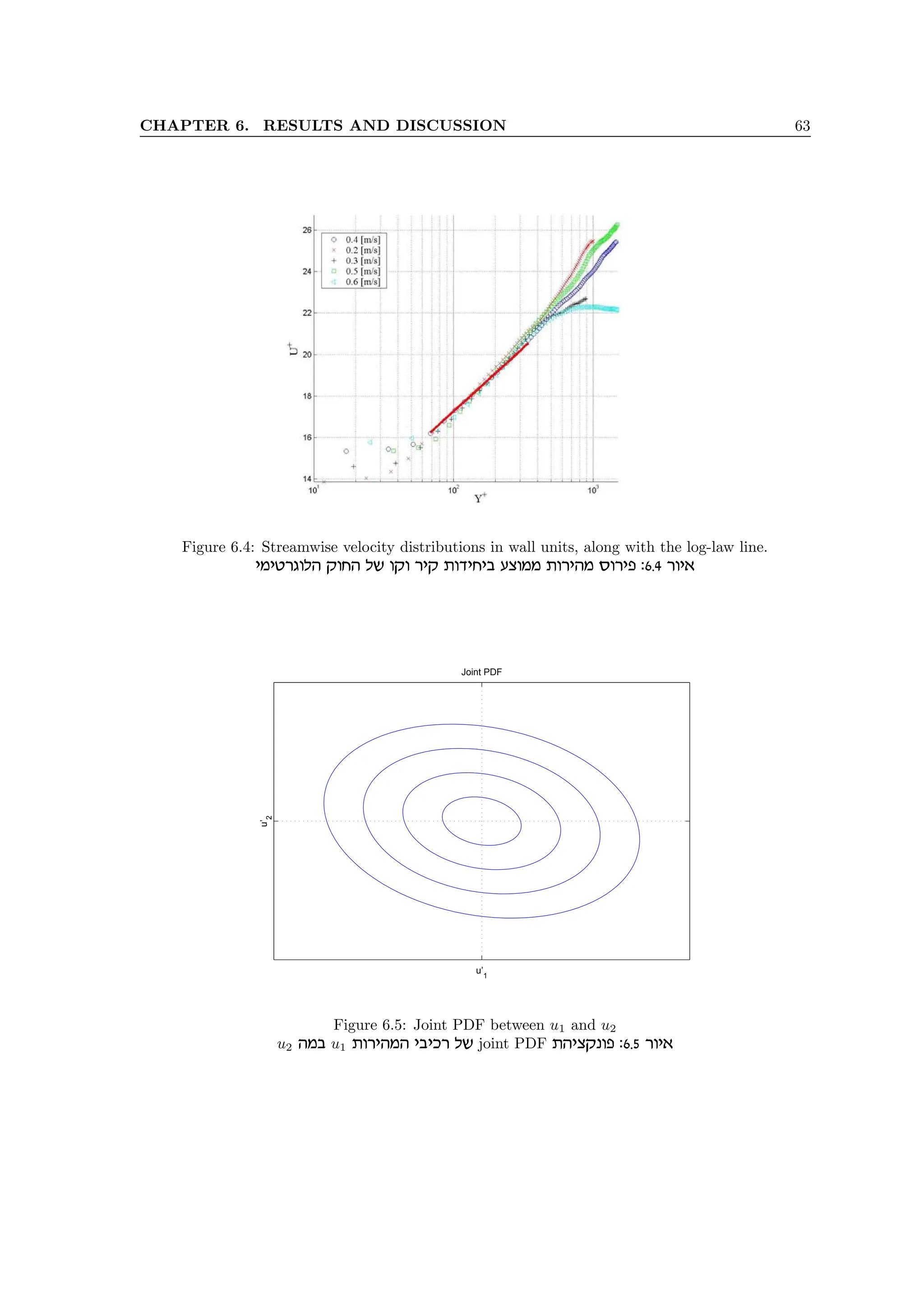

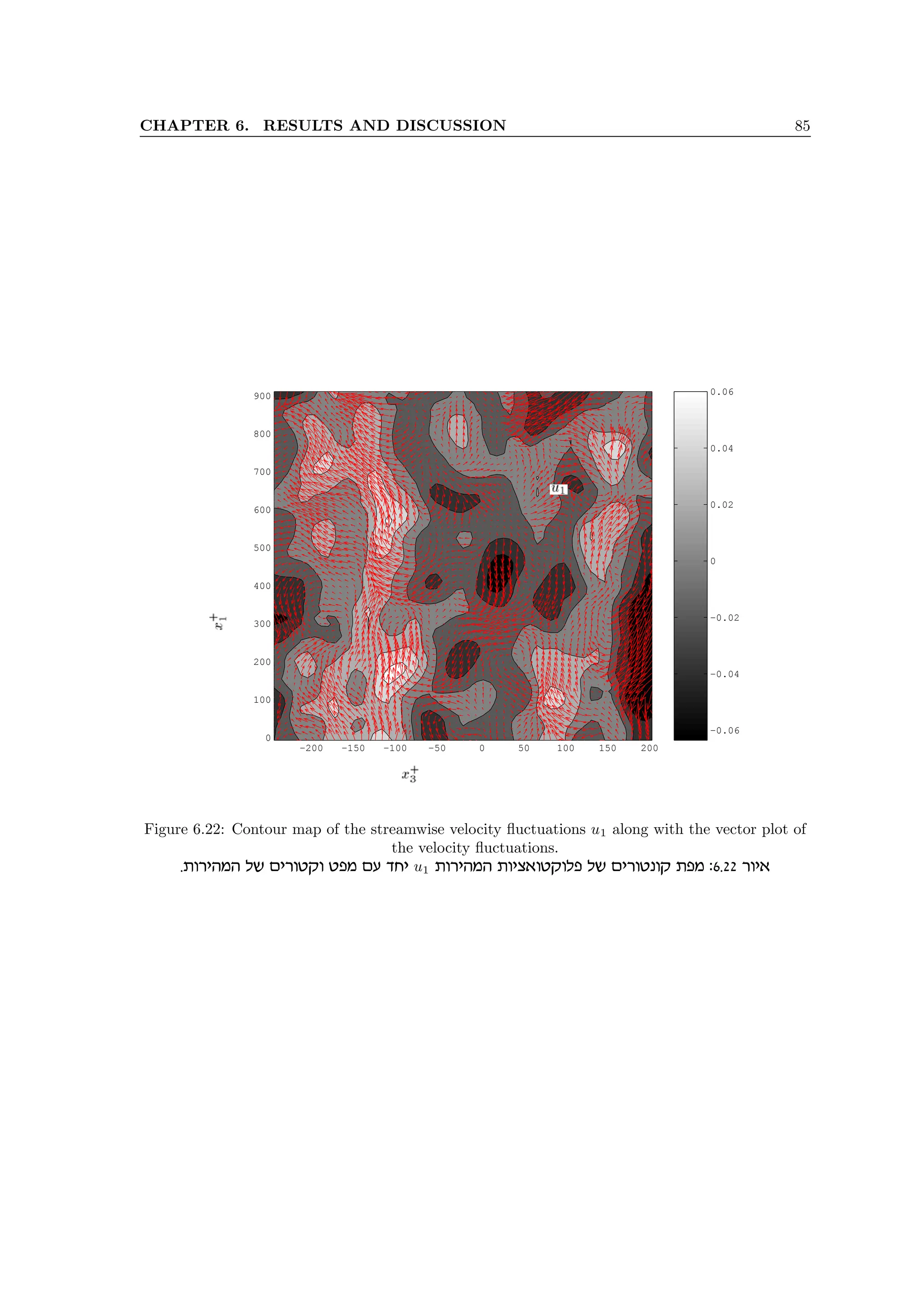

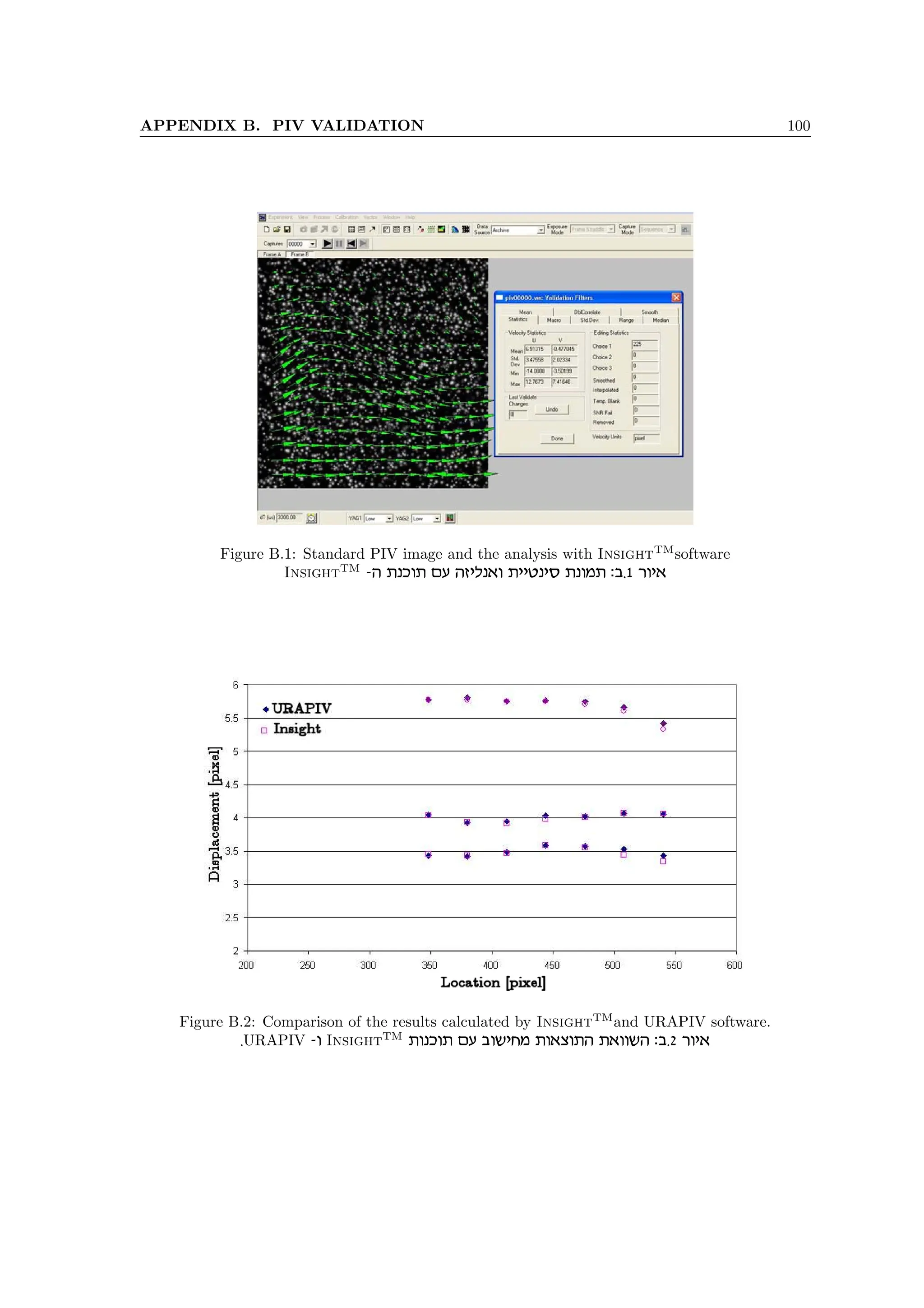

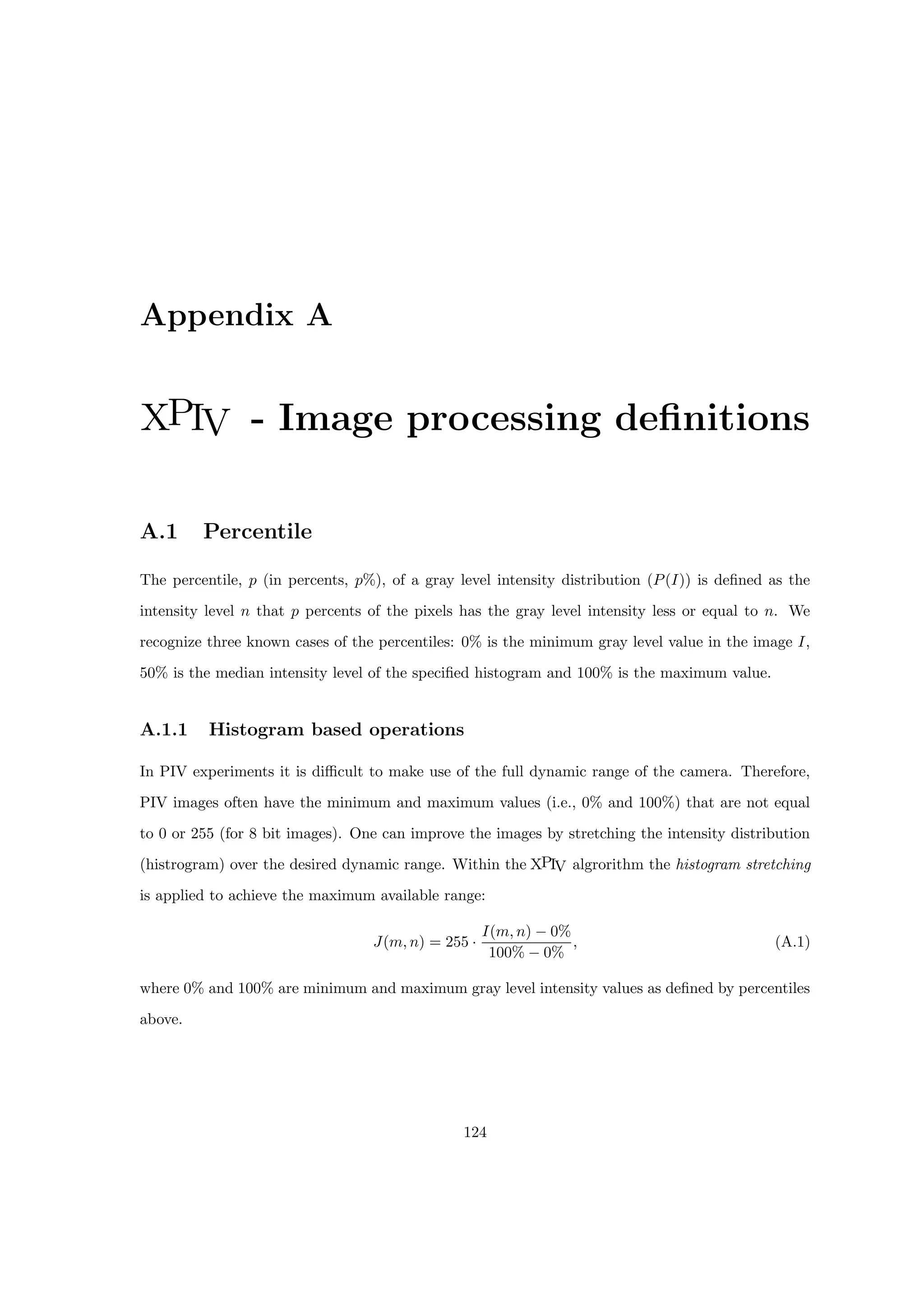

![CHAPTER 6. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 89

0.2 0.21 0.22 0.23 0.24 0.25 0.26

0.1

0.5

0.9

Figure 6.27: Streamwise velocity average profiles measured by using XPIV (-o) and box-plot of the

PIV measurements in separate y planes(|-[]-|).

.PIV -e XPIV ir cecnd ,dnixfd oeeika zrvennd zexidnd qexit :6.27 xei‘](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-101-2048.jpg)

![APPENDIX B. PIV VALIDATION 99

Case no. Q (lpm) U∞ [m/s] Qest Error, (%)

1 280 0.20 288 2.8

2 360 0.26 374 3.8

3 525 0.38 547 4.1

Table B.1: Comparison of the flow rate estimated by PIV measurements and directly measured by

flowmeter

.dwitq cn ir dcecne PIV -d ze‘vez jezn zkxreynd dwitqd oia d‘eeyd :a.1 dlah

B.2 Software performance

In order to detect possible bias error inherently introduced by some PIV algorithms, there are

two possible options (i) to analyze standard, synthetically produced images, introduced to the

PIV community by Okamoto et al. (2000), (ii) analyze the real PIV images by different soft-

ware packages. All the PIV measurements, in two dimensional, in stereoscopic and in multiplane

modes are performed by using a commercial software package InsightTM

(Inc., 1999a) that is a

part of the SPIV system. Figure B.1 presents the view of the Insight analysis of the standard

images used in the first-type evaluation analysis. The analysis is performed for the case no. 1

(http://piv.vsj.or.jp/piv/java/image01-e.html) and the evaluation shows an excellent agree-

ment between the known displacement of 7.5 ± 3 pixels and the InsightTM

analysis results in fig-

ure B.1.

The second type evaluation comparison is performed by using the URAPIV, self-made evaluation

software, developed with Matlab r

(http://urapiv.tripod.com). This software allows to analyze

PIV images by using the FFT-based cross-correlation calculation and includes the most common

velocity filters. The advantage of the URAPIV package is its open source and control of all possible

parameters. Figure B.2 depicts a comparison between the results of two software packages. The

graph includes the pixel displacements of the water flow, seeded with hollow glass sphere particles,

and evaluated by using the cross-correlation algorithm. The difference between two results is only

at the level of sub-pixel displacements and is less that 1%.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-111-2048.jpg)

![APPENDIX C. DERIVATIVES. PART 1: VORTICITY CALCULATION 118

C.3 Appendix B - Matlabr

procedures

FASTDERIVATIVE.M

function [varargout] = fastderivative(varargin)

%FASTDERIVATIVE Calculates fast derivatives of two-dimensional data

% using 2D convolution (See conv2 for more info).

% [DFDX,DFDY] = FASTDERIVATIVE(F,HX,HY,’METHOD’)

% F - 2D matrix, HX,HY - intervals in X,Y directions.

% ’method’ - one of the following methods:

% ’leastsq’ - 5 points

% ’richardson’ - 5 points

% ’center’ - 3 points, center difference

% ’general’ - default, forward/backward/center in one

% ’5point’ - richardson plus forward/backward on boundaries

%

% [DFDX,DFDY] = FASTDERIVATIVE(F,H,’METHOD’)

% Uses HY = HX = H,

%

% [DFDX,DFDY] = FASTDERIVATIVE(F,’METHOD’)

% Uses default HX,HY = 1.

% Created: 05-Mar-2001

% Author: Alex Liberzon

% E-Mail : liberzon@tx.technion.ac.il

% Phone : +972 (0)48 29 3861

% Copyright (c) 2001 Technion - Israel Institute of Technology

%

% Modified at: 05-Mar-2001

% $Revision: 1.0 $ $Date: 05-Mar-2001 11:59:07$

% Parse inputs

if nargin == 4

[f,hx,hy,method] = deal(varargin{:});

elseif nargin == 3

[f,hx,method] = deal(varargin{:});](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-130-2048.jpg)

![APPENDIX C. DERIVATIVES. PART 1: VORTICITY CALCULATION 119

hy = hx;

elseif nargin == 2

[f,method] = deal(varargin{:});

hx = 1; hy = 1;

end;

switch lower(method)%

case ’general’,’default’,’3points’,’threepoints’}

dfdx = -conv2([0 1 0],[-1 0 1],f,’same’)/2/hx;

dfdy = -conv2([-1 0 1],[0 1 0],f,’same’)/2/hy;

dfdx(:,1) = f(:,2)-f(:,1);

dfdx(:,end) = -f(:,end-1)+f(:,end);

dfdy(1,:) = f(2,:)-f(1,:);

dfdy(end,:) = -f(end-1,:)+f(end,:);

case {’leastsq’}

dfdx = -conv2([0 0 1 0 0],[-2 -1 0 1 2],f,’valid’)/10/hx;

dfdy = -conv2([-2 -1 0 1 2],[0 0 1 0 0],f,’valid’)/10/hy;

case {’center’}

dfdx = -conv2([0 1 0],[-1 0 1],f,’valid’)/2/hx;

dfdy = -conv2([-1 0 1],[0 1 0],f,’valid’)/2/hy;

case {’richardson’}

dfdx = -conv2([0 0 1 0 0],[1 -8 0 8 -1],f,’valid’)/12/hx;

dfdy = -conv2([1 -8 0 8 -1],[0 0 1 0 0],f,’valid’)/12/hy;

otherwise

error(’Wrong method, see HELP FASTDERIVATIVE ’);

end

varargout{1} = dfdx;%

varargout{2} = dfdy;%

VORTICITY.M

function [varargout] = vorticity(varargin)

%VORTICITY Calculates vorticity and checks the continuity equation.

% [OMEGA,EZZ] = VORTICITY(X,Y,U,V,METHOD)

% returns the vorticity OMEGA and Z-component of the strain EZZ.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-131-2048.jpg)

![APPENDIX C. DERIVATIVES. PART 1: VORTICITY CALCULATION 120

%

%

%

% See also FASTDERIVATIVE, PROCS_V4

%

% Created: 02-Mar-2001

% Author: Alex Liberzon

% E-Mail : liberzon@tx.technion.ac.il

% Phone : +972 (0)48 29 3861

% Copyright (c) 2001 Technion - Israel Institute of Technology

%

% Modified at: 05-Mar-2001

% $Revision: 1.02 $ $Date: 05-Mar-2001 23:12:01$

% Inputs:

% The simplest case

[x,y,u,v,method] = deal(varargin{:});

% Parameters:

% Homogeneous grid spacing - the simplest case

DeltaX = max(abs(diff(x(1:2,1))),abs(diff(x(1,1:2))));%

DeltaY = max(abs(diff(y(1:2,1))),abs(diff(y(1,1:2))));%

switch lower(method)%

case {’circulation’,’circ’}

dx=(1/(8*DeltaX)).*...

[-1 0 1

-2 0 2

-1 0 1];

dy=(1/(8*DeltaY)).*...

[-1 -2 -1

0 0 0

1 2 1];

vort = - conv2(v,dx,’valid’) + conv2(u,dy,’valid’);

dvdy = conv2(v,dx,’valid’);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-132-2048.jpg)

![APPENDIX C. DERIVATIVES. PART 1: VORTICITY CALCULATION 121

dudx = conv2(u,dy,’valid’);

cont = dudx + dvdy;

case {’richardson’}

[dudx,dudy] = fastderivative(u,DeltaX,DeltaY,’richardson’);

[dvdx,dvdy] = fastderivative(v,DeltaX,DeltaY,’richardson’);

vort = dvdx - dudy;

cont = dudx + dvdy;

case {’leastsquares’,’leastsq’}

[dudx,dudy] = fastderivative(u,DeltaX,DeltaY,’leastsq’);

[dvdx,dvdy] = fastderivative(v,DeltaX,DeltaY,’leastsq’);

vort = dvdx - dudy;

cont = dudx + dvdy;

case {’center’}

[dudx,dudy] = fastderivative(u,DeltaX,DeltaY,’center’);

[dvdx,dvdy] = fastderivative(v,DeltaX,DeltaY,’center’);

vort = dvdx - dudy;

cont = dudx + dvdy;

otherwise

disp(’Wrong method’);

end

varargout{1} = vort; varargout{2} = cont;

Simulation procedure: PROCS V4.M

clear all%

[x,y,u,v,vort,dU] = vortex_flow(1,1,1,0);%

indx = 0; indy = 0;

for N = [100,500,1000]

indx = indx + 1;

indy = 0;

for errorlevel = [0.02 0.05 0.075]

indy = indy + 1;

U = zeros([size(u),N]);

V = zeros([size(u),N]);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-133-2048.jpg)

![APPENDIX C. DERIVATIVES. PART 1: VORTICITY CALCULATION 122

% Monte Carlo:

for i = 1:N,

U(:,:,i) = u + normrnd(0,errorlevel*max(u(:))/1.96,[size(u)]);

end

for i = 1:N,

V(:,:,i) = v + normrnd(0,errorlevel*max(v(:))/1.96,[size(v)]);

end

[omegar,contr,omegal,contl] = deal(zeros(47,47,N));

[omegac,contc,omega3,cont3] = deal(zeros(49,49,N));

for i = 1:N,

[omegar(:,:,i),contr(:,:,i)] = vorticity_v4(x,y,U(:,:,i),V(:,:,i),’richardson’);

[omega3(:,:,i),cont3(:,:,i)] = vorticity_v4(x,y,U(:,:,i),V(:,:,i),’center’);

[omegal(:,:,i),contl(:,:,i)] = vorticity_v4(x,y,U(:,:,i),V(:,:,i),’leastsq’);

[omegac(:,:,i),contc(:,:,i)] = vorticity_v4(x,y,U(:,:,i),V(:,:,i),’circulation’);%

end;

% End of calculations

% Relative error = (mean(omegaI(:,:,i),3) - vort)/rms(vort);

relerror3(indx,indy) = rms((mean(omega3,3)-vort(2:end-1,2:end-1))/...

rms(vort(2:end-1,2:end-1)));

relerrorc(indx,indy) = rms((mean(omegac,3)-vort(2:end-1,2:end-1))/...

rms(vort(2:end-1,2:end-1)));

relerrorr(indx,indy) = rms((mean(omegar,3)-vort(3:end-2,3:end-2))/...

rms(vort(3:end-2,3:end-2)));

relerrorl(indx,indy) = rms((mean(omegal,3)-vort(3:end-2,3:end-2))/...

rms(vort(3:end-2,3:end-2)));

end% End of errorlevel loop

end% End of N loop

% Continuity check

figure,subplot(221),

pcolor(mean(cont3,3)),shading interp, colorbar horiz

title(’3 point, center difference’);

subplot(222),pcolor(mean(contr,3)),shading interp, colorbar horiz](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-134-2048.jpg)

![APPENDIX A. XPIV - IMAGE PROCESSING DEFINITIONS 125

A.1.2 Derivative based operations

Since digital image processing techniques deal with discrete digitized images presented over the

rectangular grid, I(m, n), the derivative based operations lie on the derivative approximations. Thus

the image gradient ∇I is approximated by the sum of two convolutions in row-wise and column-wise

directions, denoted as x and y, respectively:

∇I = (hx ⊗ I)x + (hy ⊗ I)y

where subscripts x and y denote the projections on the x or y axis. Thus, the gradient magnitude

is defined as:

Ig =

q

(hx ⊗ I)

2

+ (hy ⊗ I)

2

.

There are many possible operators for hx and hy and most simple ones are [1 − 1] or [1 0 − 1] as

hx and their transposes, hy = ht

x.

A.2 Morphology based operations

In morphology based operations, we refer to the image (either binary or intensity level) as a set of

objects and background (Serra, 1982, Giardina, 1988):

I = {x |I(x) ⊂ Y }

where Y is the set under R2

that satisfies some predefined property. For example, for the binary

image of 0’s and 1’s, objects are all pixels that are equal to 1, i.e. I = {x |I(x) = 1}. The background

or in other definition, complement of I is defined as all elements that are not in set of I:

Ic

= {x |x /

∈ I}

Each object can be treated by one of four basic operators: union ∪, intersection ∩, complement c

and translation, which is defined for set I and vector b as:

I + b = {x + b |x ∈ I}

or in other words, all pixels that are covered by set I (an object) by shifting, as it is defined in vector

b.

Two basic mathematical morphology operations for binary sets {0, 1} are defined as following:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-137-2048.jpg)

![APPENDIX A. XPIV - IMAGE PROCESSING DEFINITIONS 127

Gradient:

Ig =

1

2

((I ⊕ B) − (I B))

Laplacian:

∇2

= IL =

1

2

[((I ⊕ B) − I) − (I − (I B))] =

=

1

2

((I ⊕ B) + (I B) − 2I)

Background correction:

ˆ

IB = I − ˜

IB

A.3 Segmentation

Segmentation is one of the most common operations in high-level image processing and computer

vision. The target is to distinguish between the ”objects” and the ”background” and the most

popular techniques are thresholding and edge detection.

Thresholding:

IT = {x |I(x) ≥ T}

where T is the threshold. The threshold can be defined arbitrarily or by using one of the

common techniques defined on the histogram of the image. The isodata algorithm, for example,

is an iterative technique (Ridler and Calvard, 1978), where histogram is divided into two groups

by its mean value, and in the following iterations the threshold is defined as the average of

two mean values of each group, until the difference is insignificant. Another common and

fast technique is entitled background symmetry algorithm. This algorithm is based on the

assumption that the maximum peak within the histogram is of the background and uses

percentiles to define the limits of the background population. Then, using the symmetry

assumption, the threshold is defined as:

T = max {P(I)} − (p% − max {P(I)}) .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-139-2048.jpg)

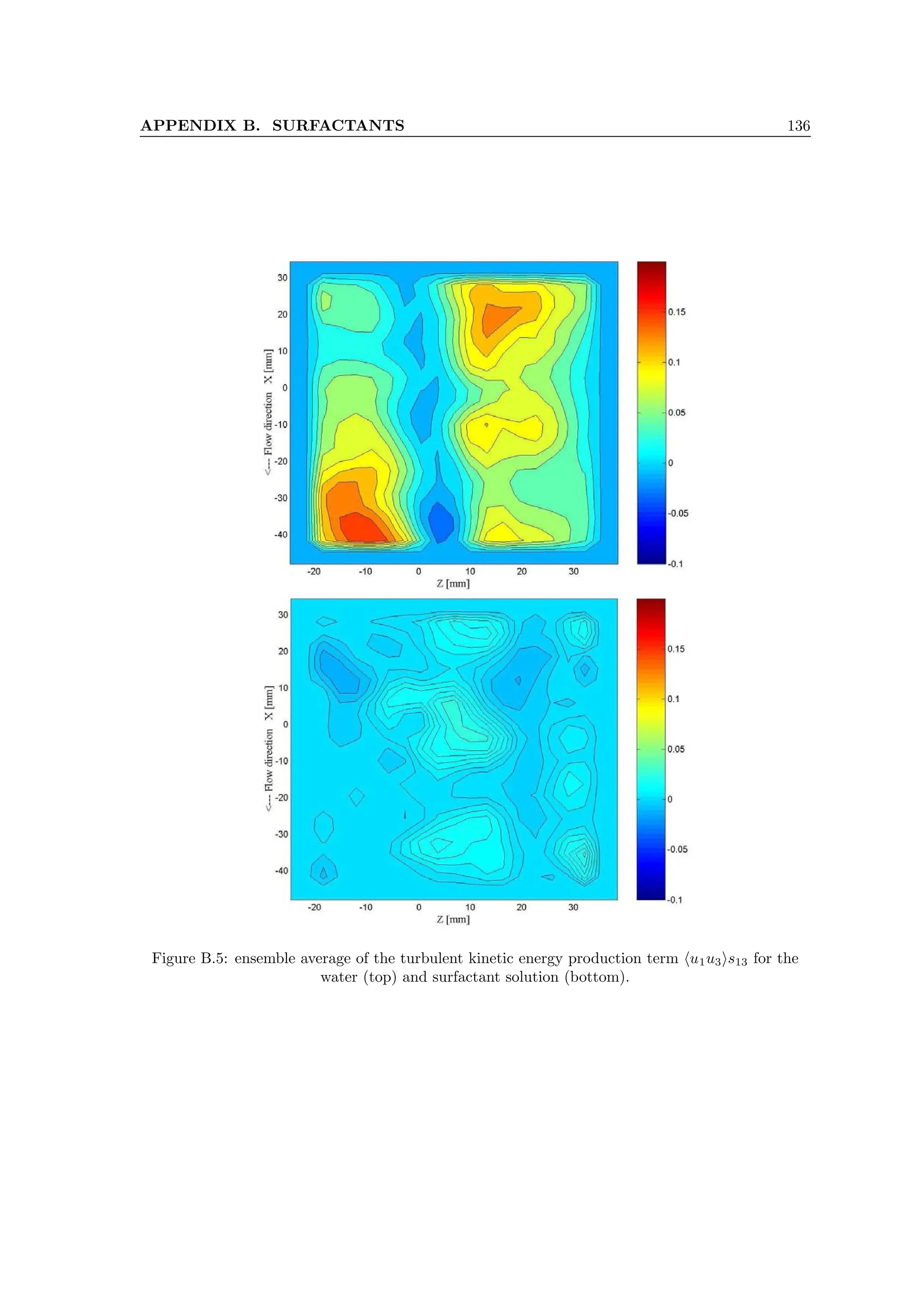

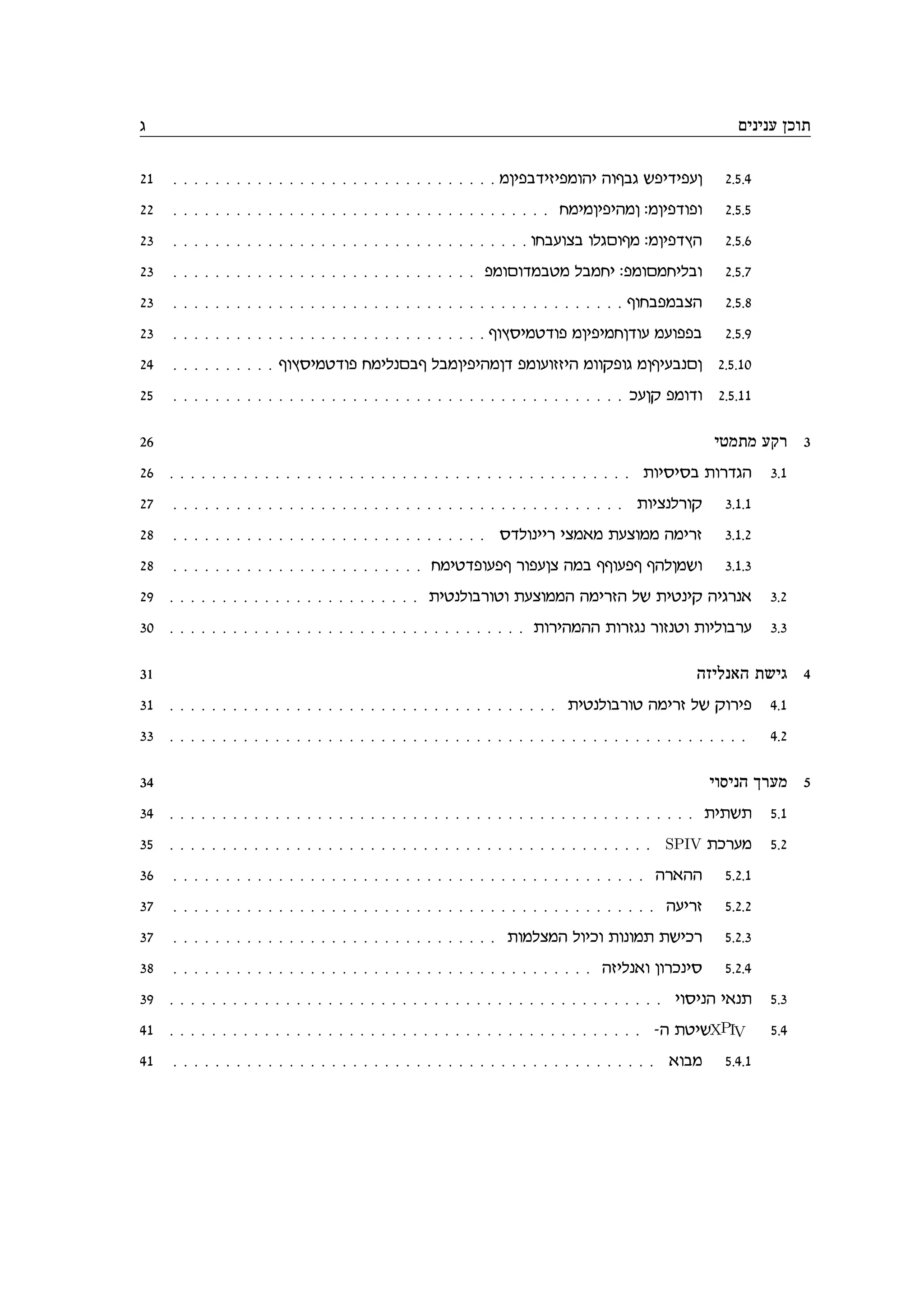

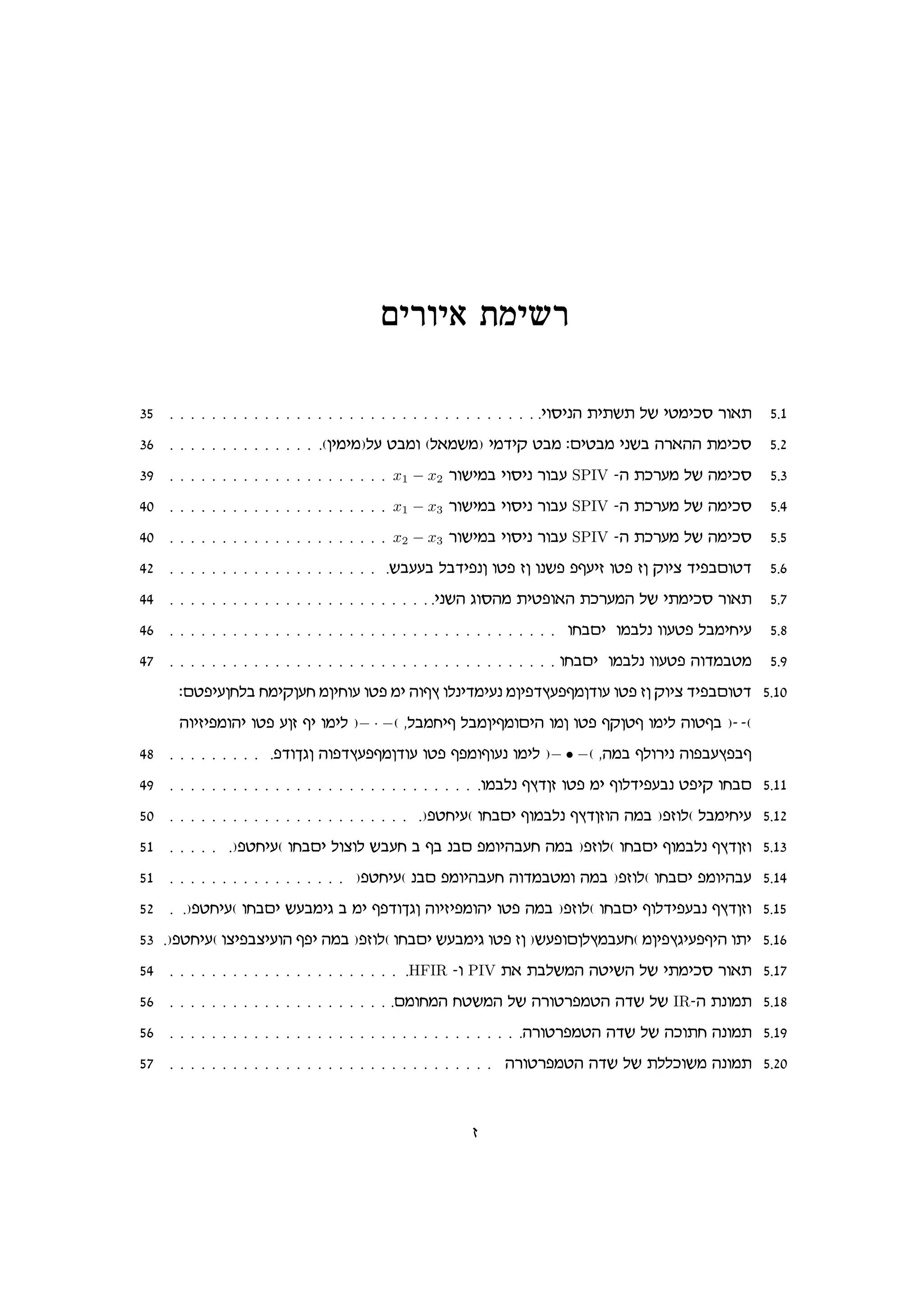

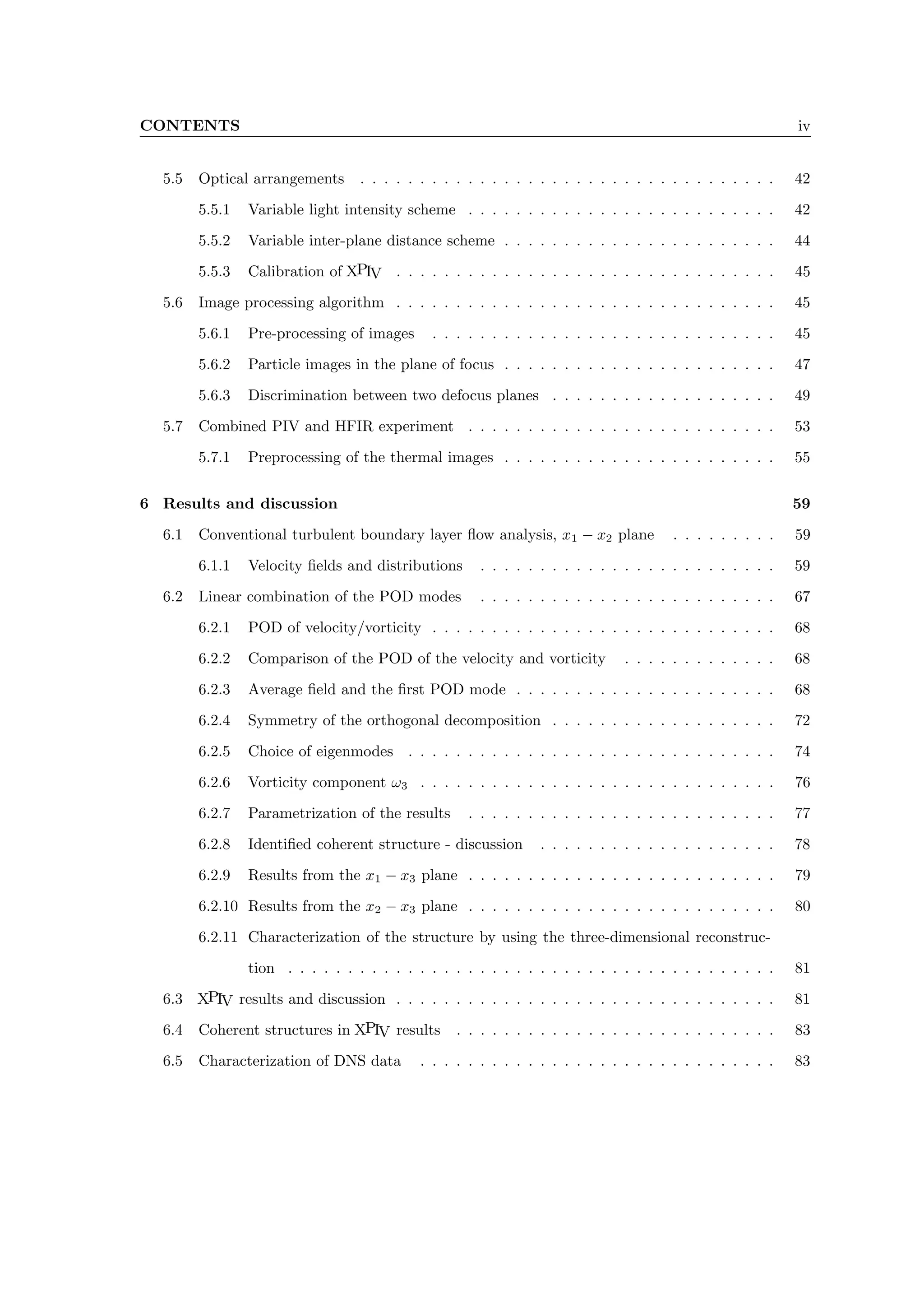

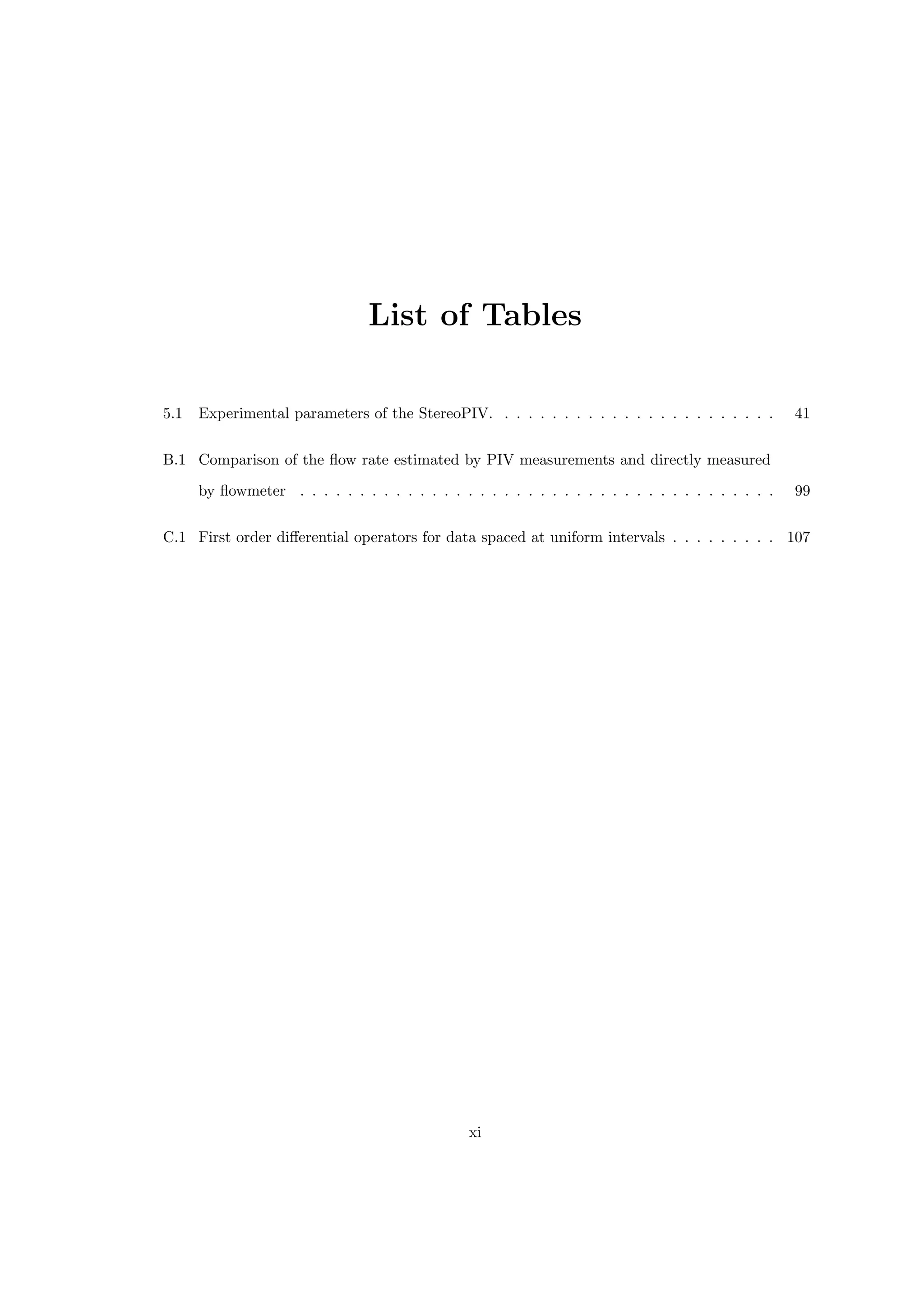

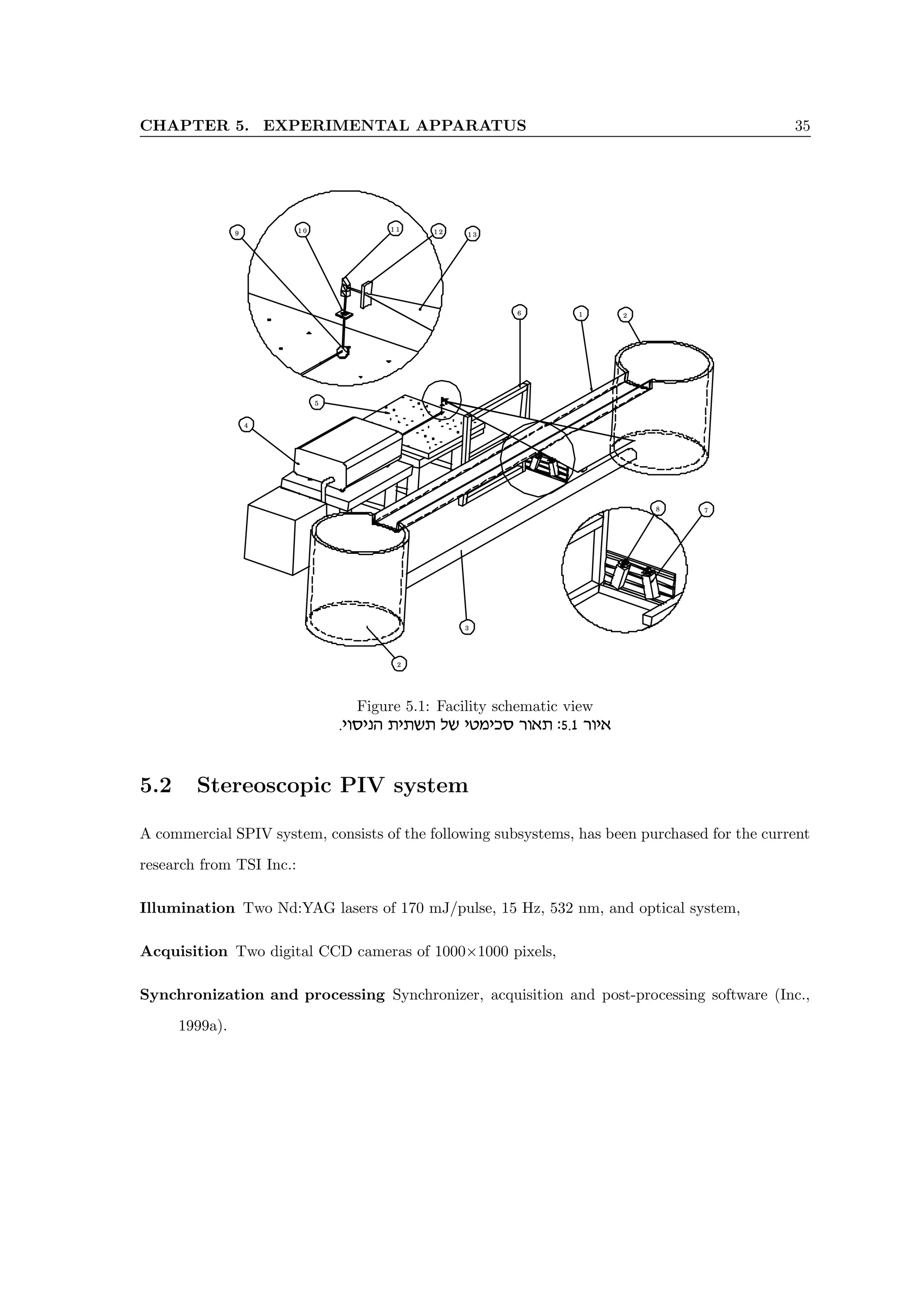

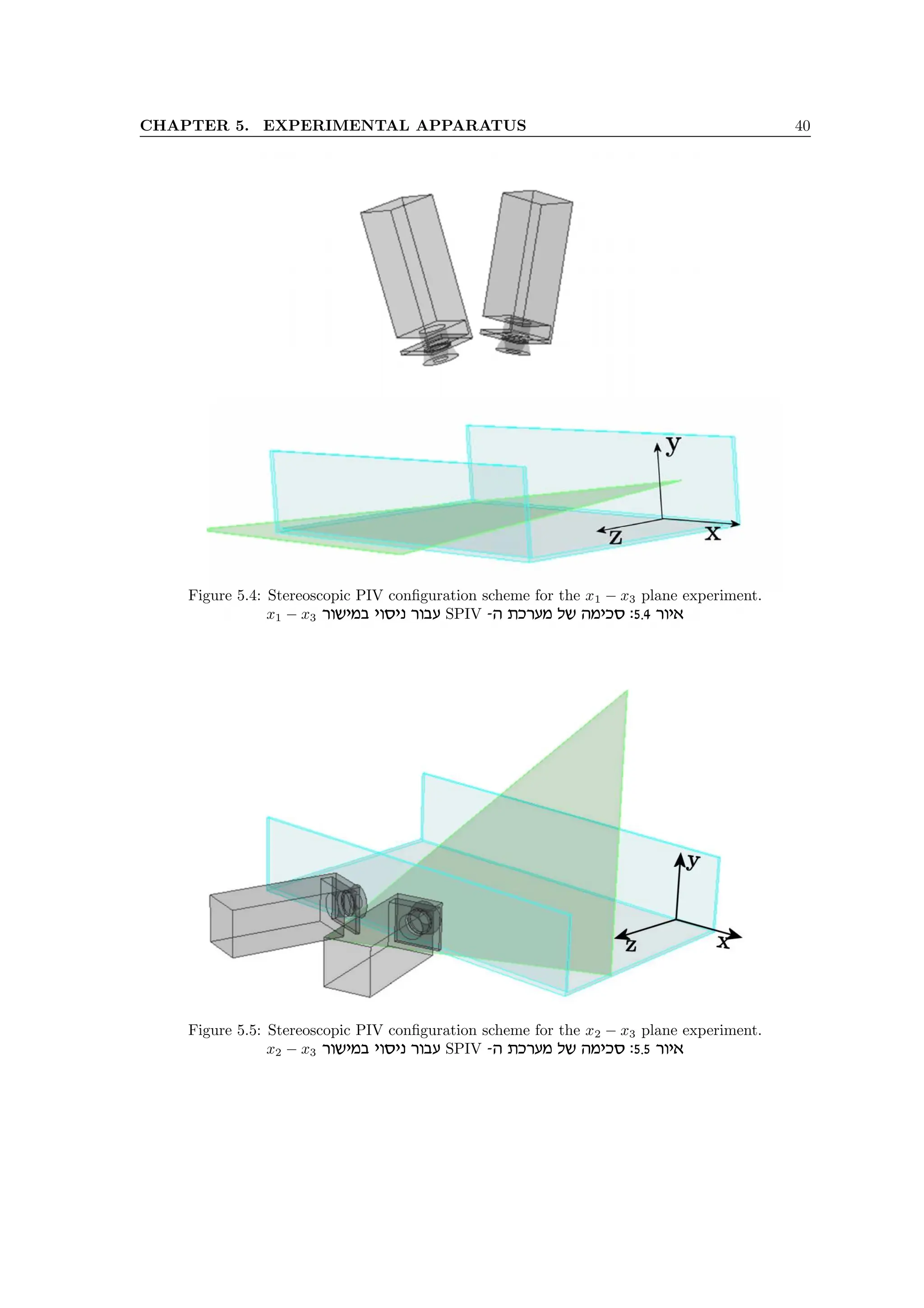

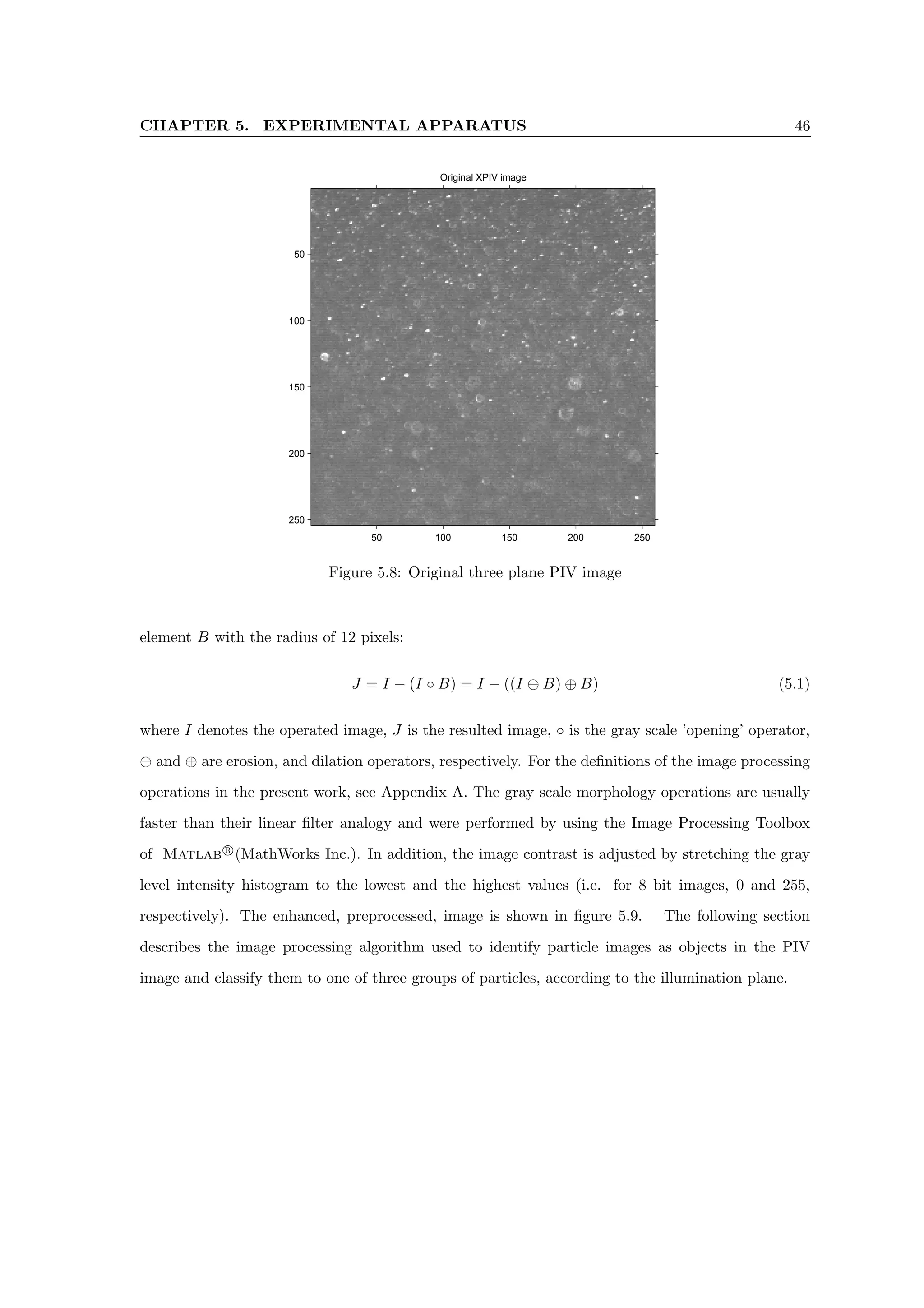

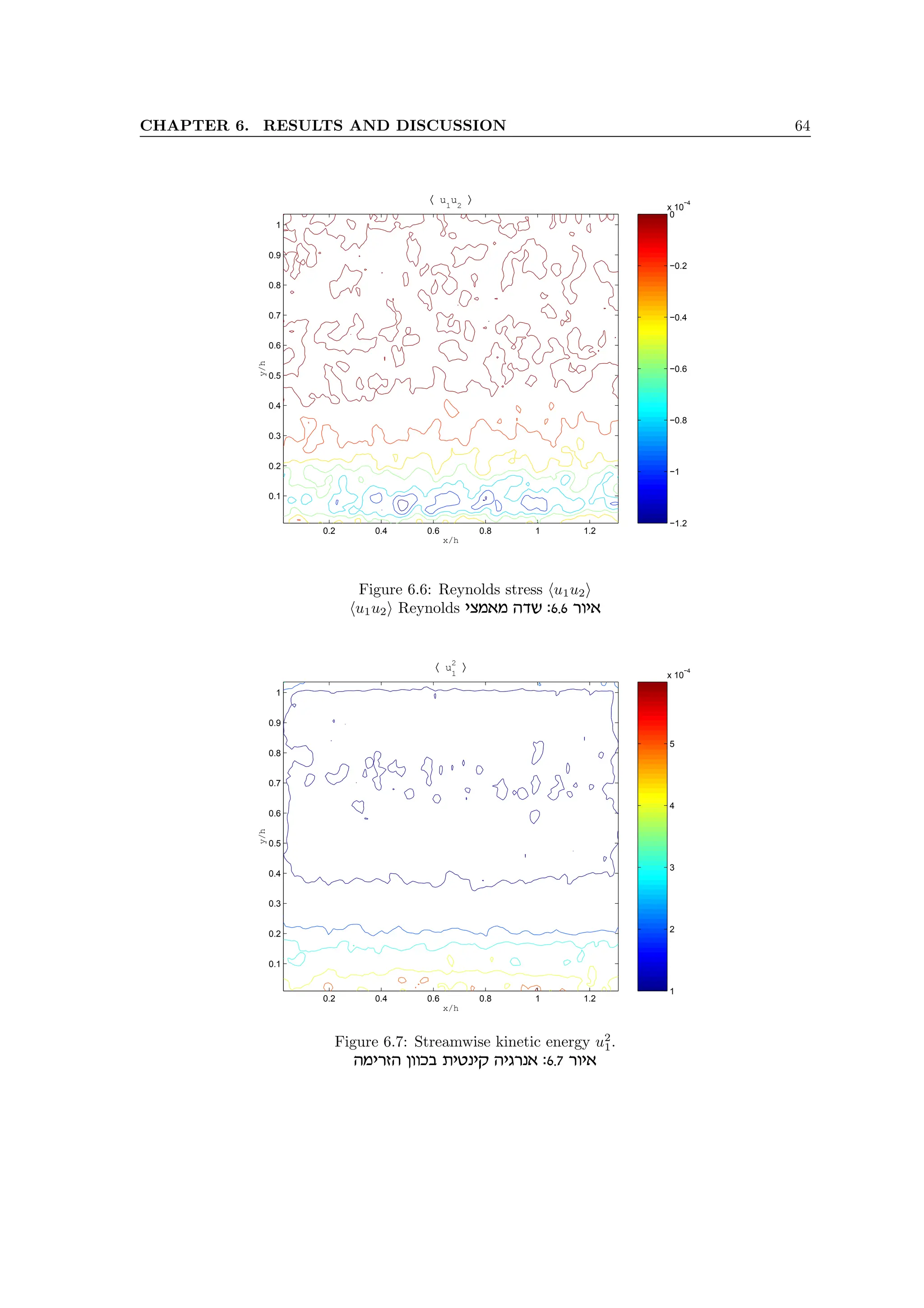

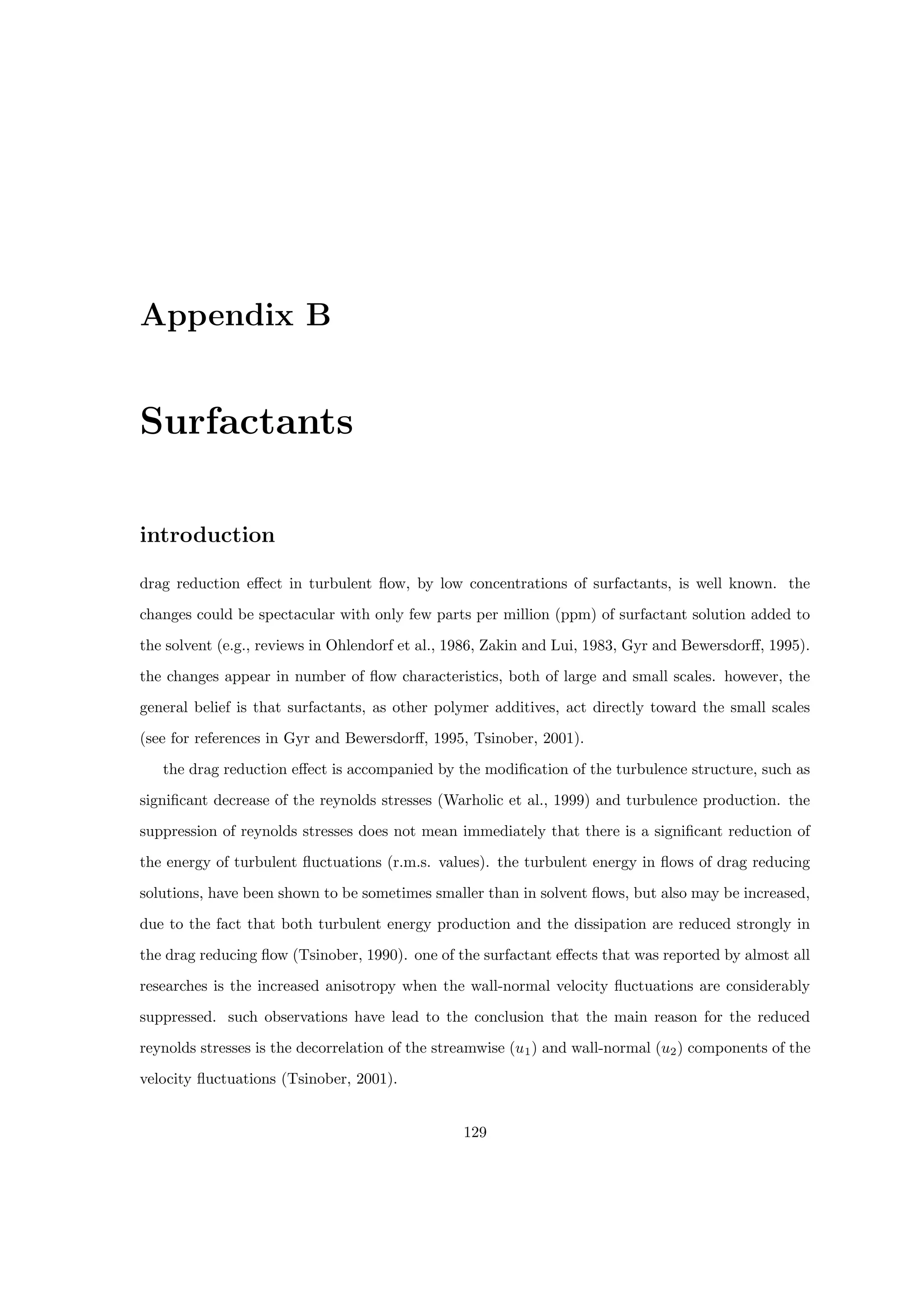

![APPENDIX B. SURFACTANTS 133

0.03

0.035

0.04

0.045

0.05

0.055

0.06

0.065

0.07

0.075

0.08

−20 −10 0 10 20 30

−40

−30

−20

−10

0

10

20

30

Z [mm]

X

[mm]

0.03

0.035

0.04

0.045

0.05

0.055

0.06

0.065

0.07

0.075

0.08

−20 −10 0 10 20 30

−40

−30

−20

−10

0

10

20

30

Z [mm]

X

[mm]

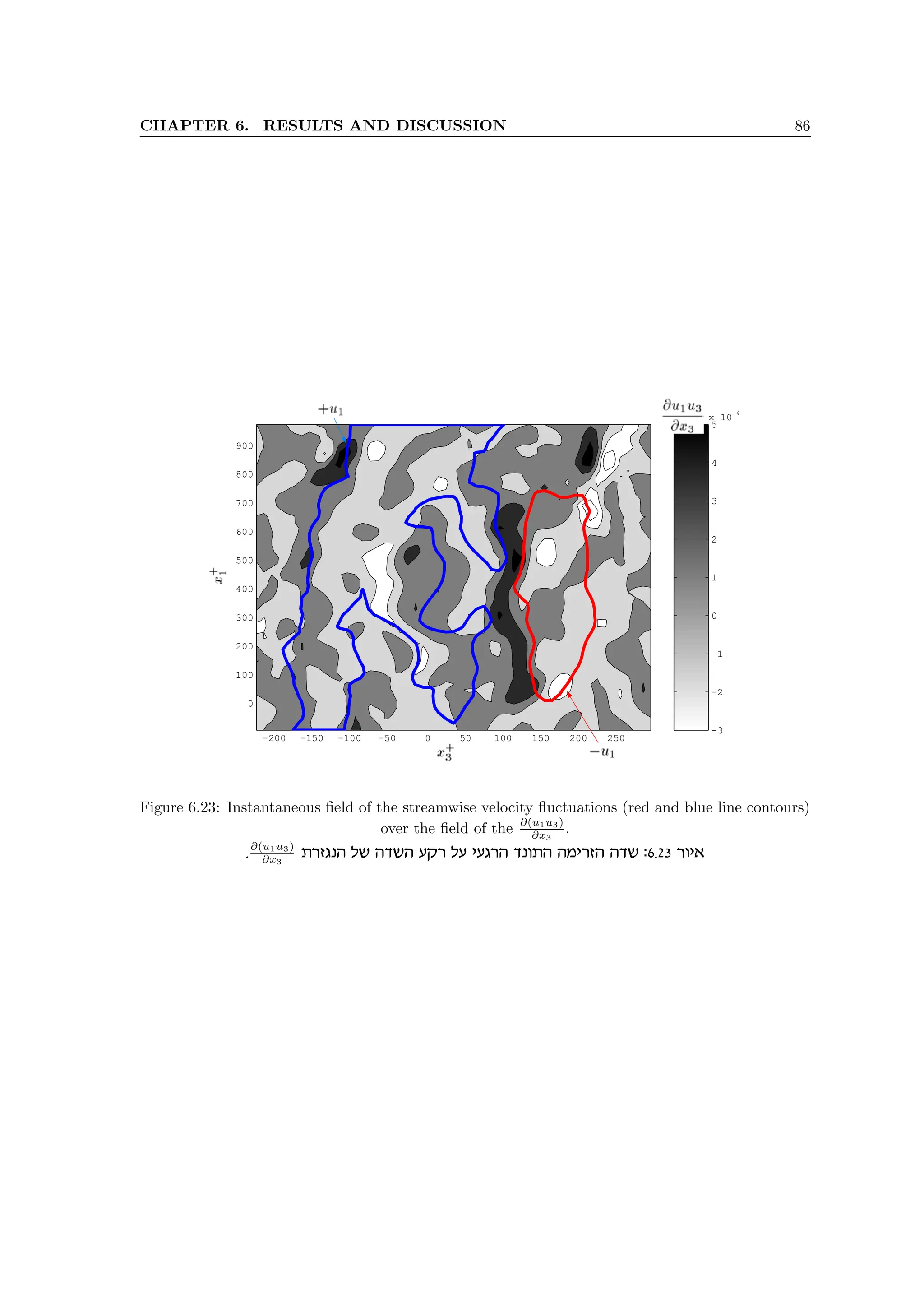

Figure B.2: ensemble average of the turbulent intensity

p

hu2

1i/uq for the water (top) and

surfactant solution (bottom).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-145-2048.jpg)

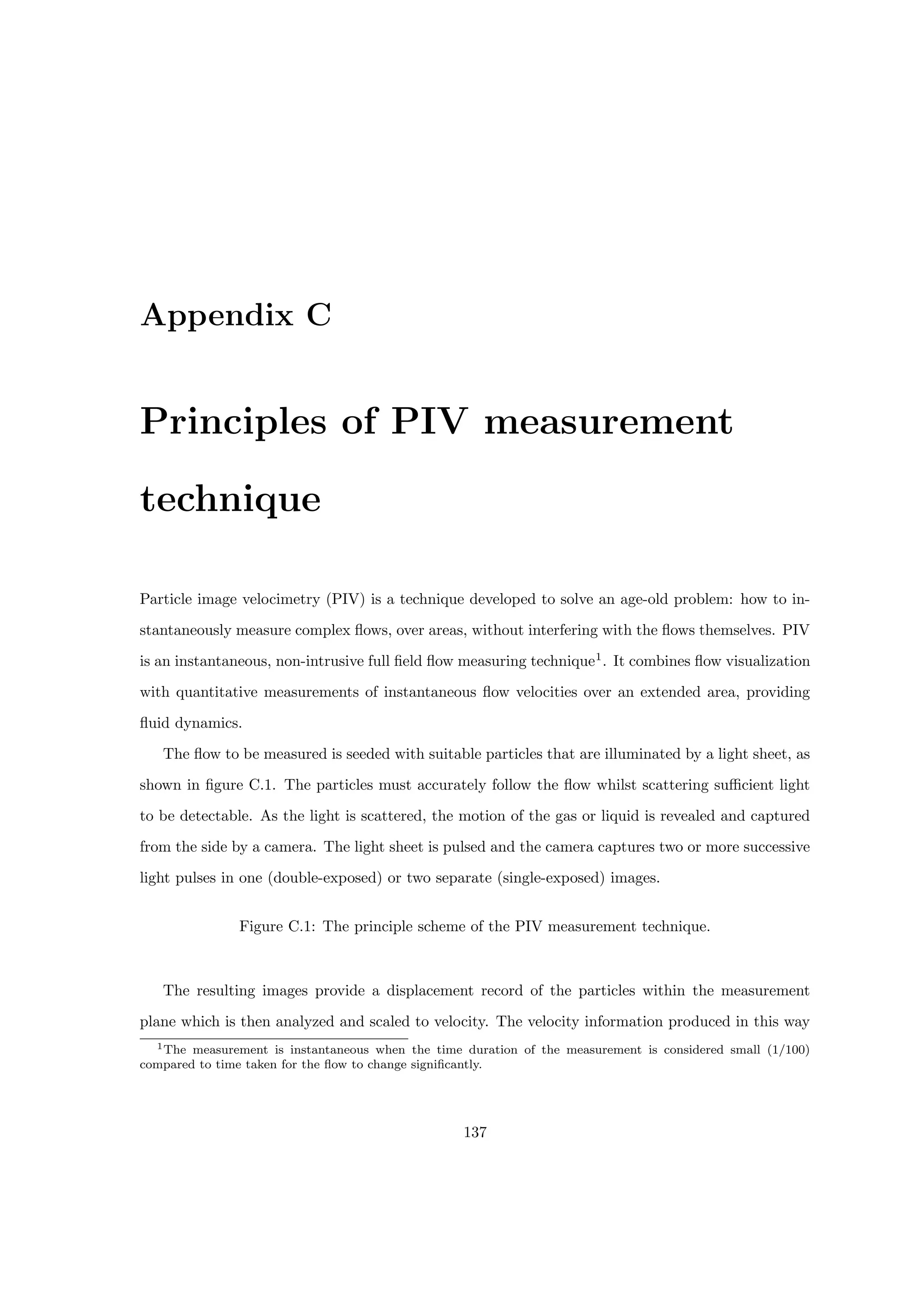

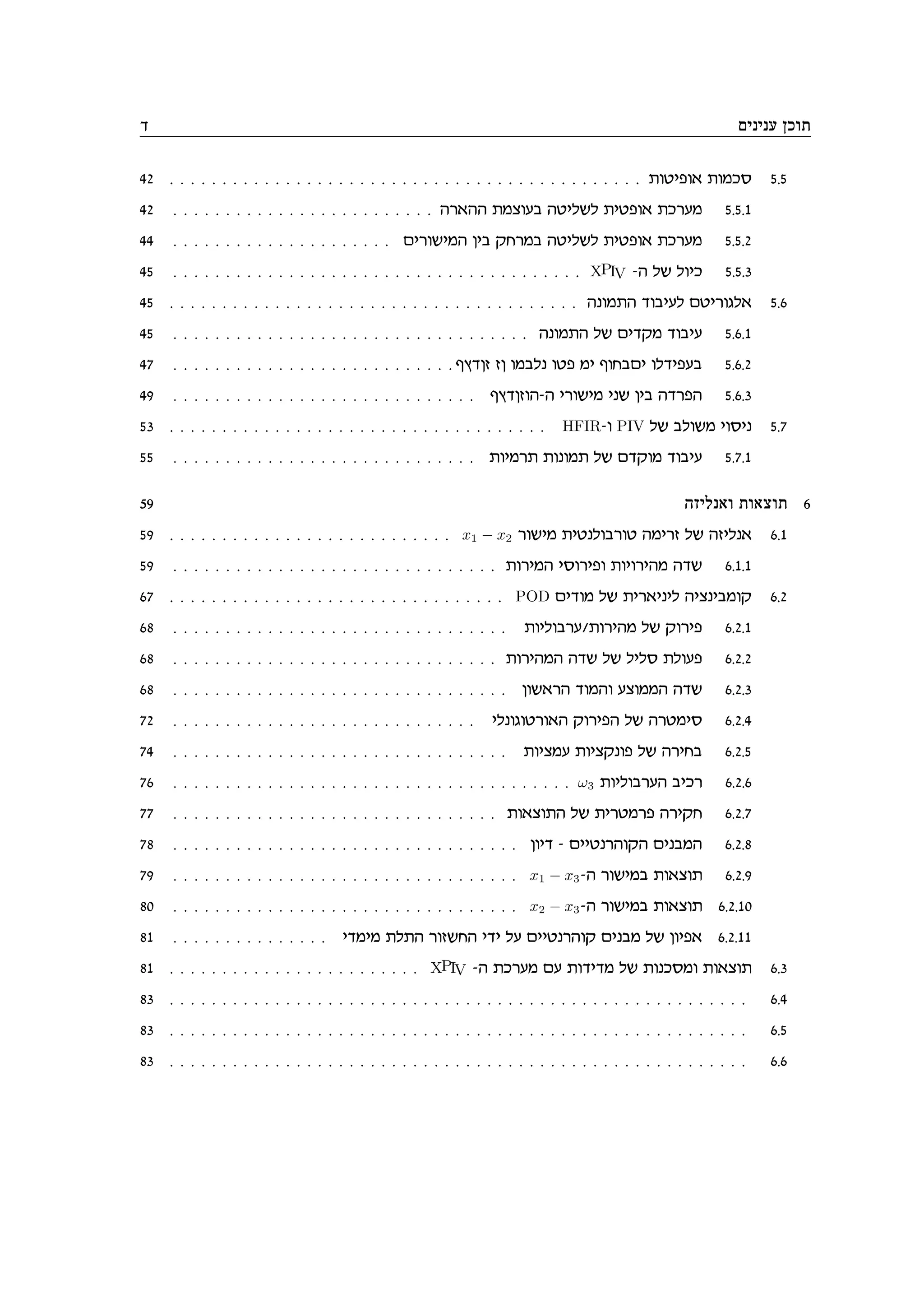

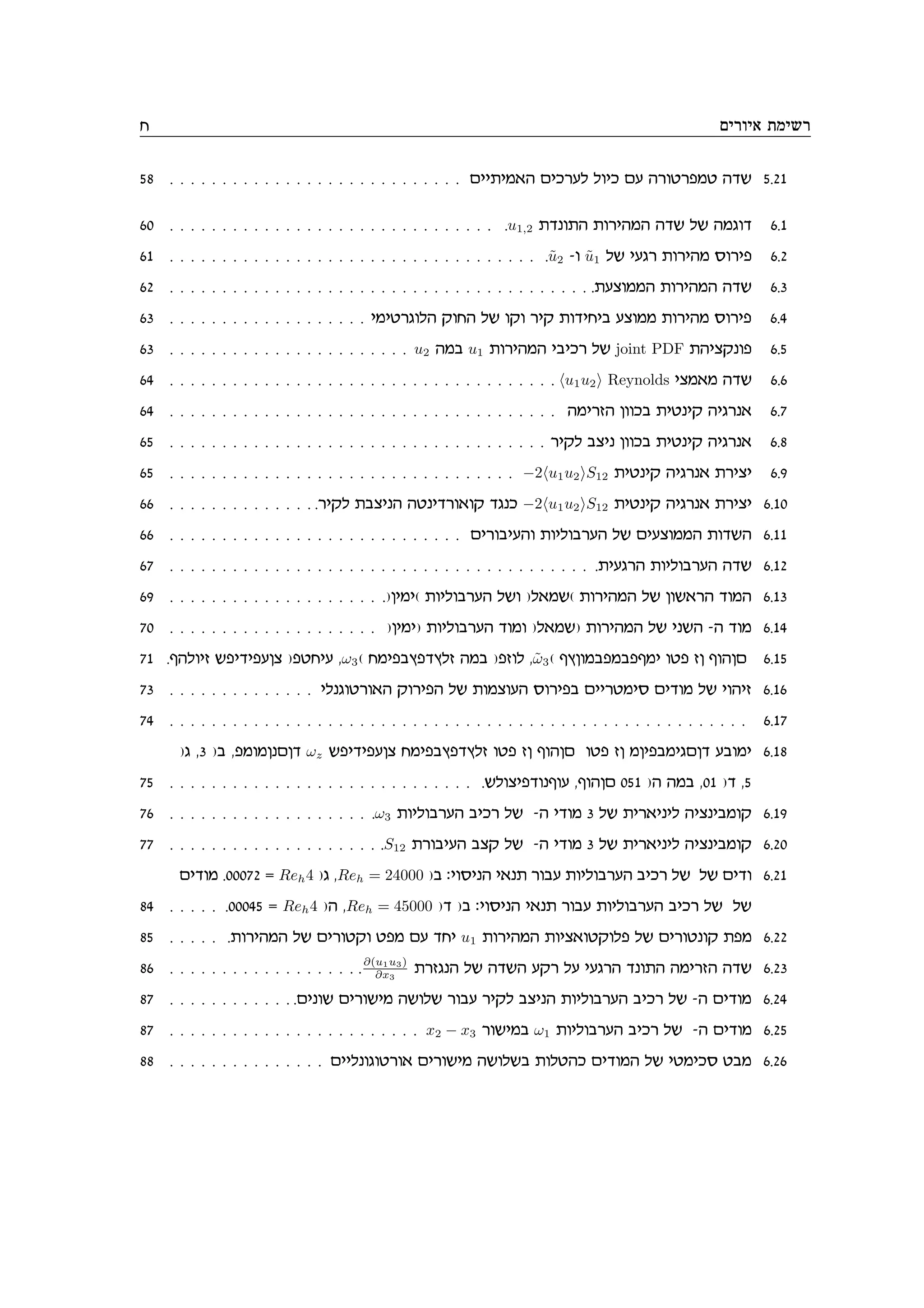

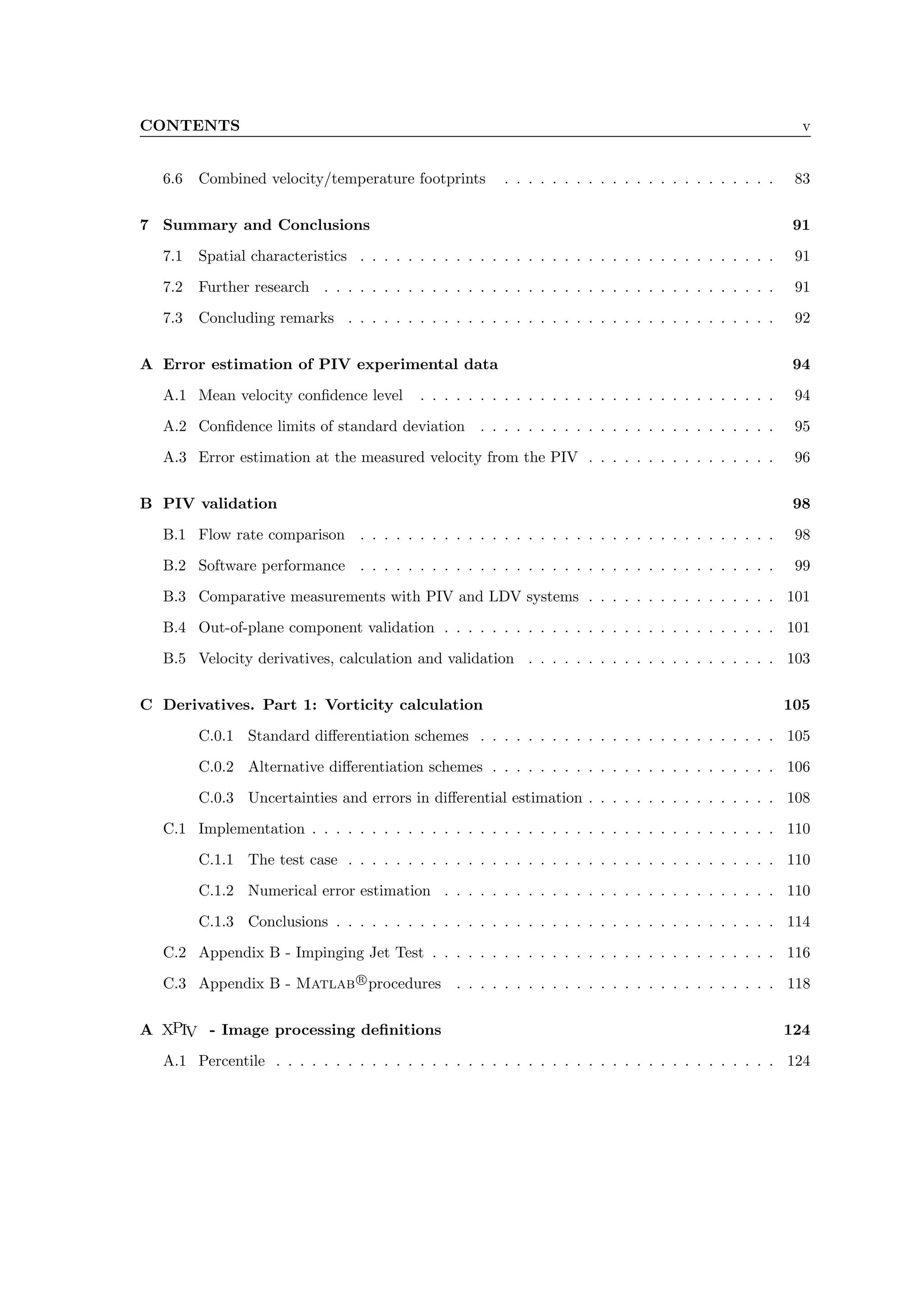

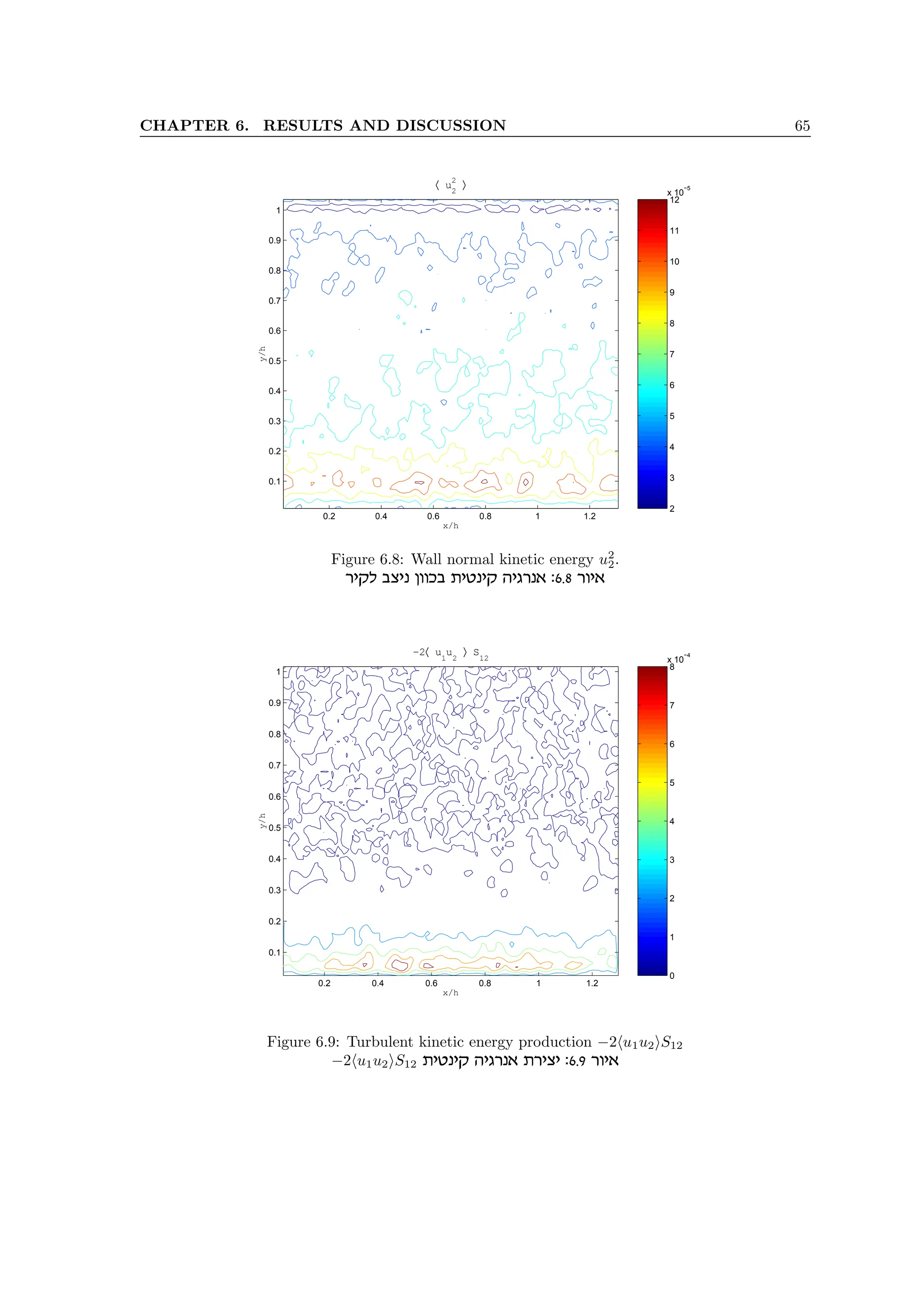

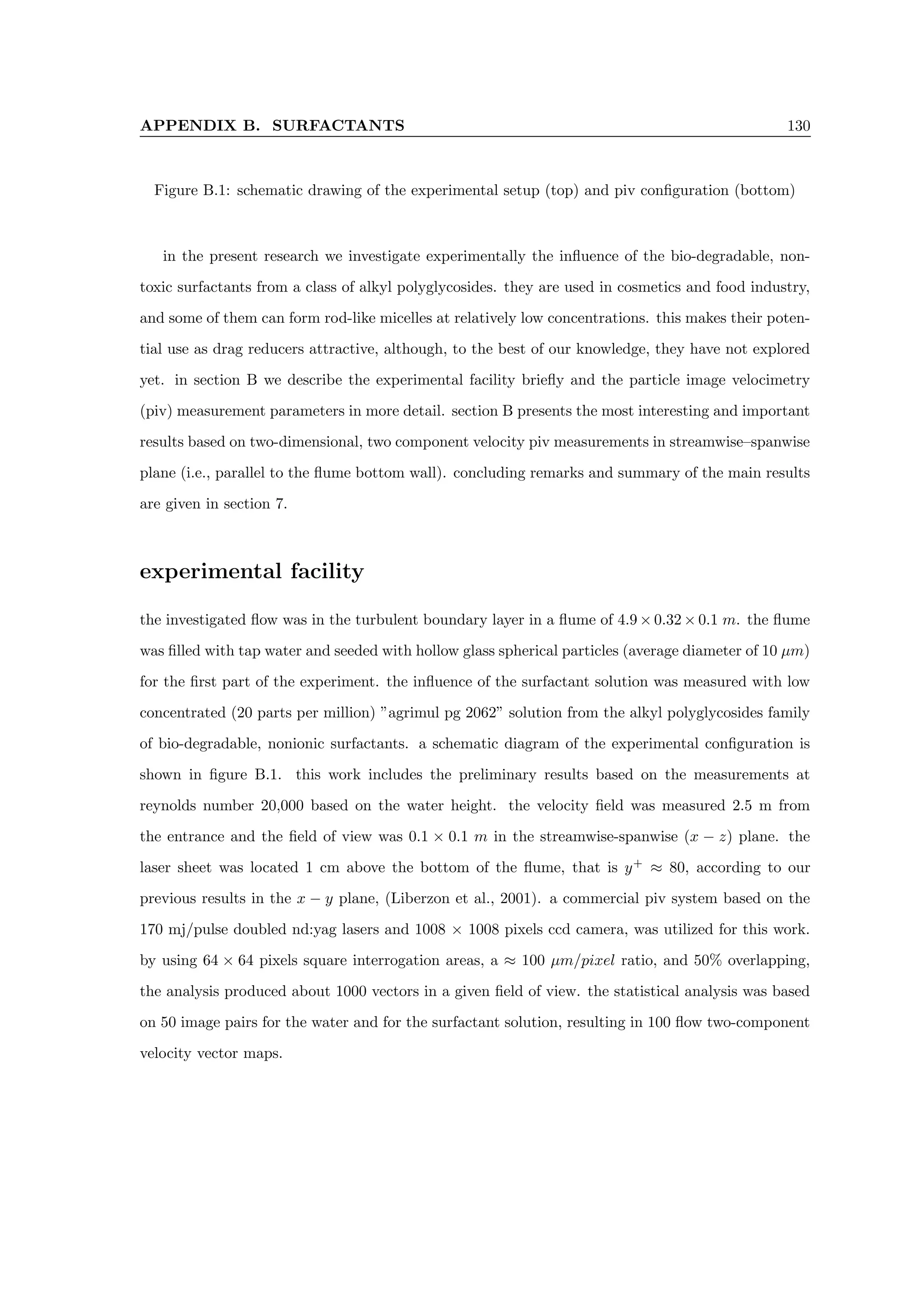

![APPENDIX B. SURFACTANTS 134

−0.08

−0.06

−0.04

−0.02

0

0.02

0.04

−20 −10 0 10 20 30

−40

−30

−20

−10

0

10

20

30

Z [mm]

X

[mm]

−0.08

−0.06

−0.04

−0.02

0

0.02

0.04

−20 −10 0 10 20 30

−40

−30

−20

−10

0

10

20

30

Z [mm]

X

[mm]

Figure B.3: ensemble average of the one-point correlation between streamwise and spanwise

velocity fluctuations hu1u3i for the water (top) and surfactant solution (bottom).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-146-2048.jpg)

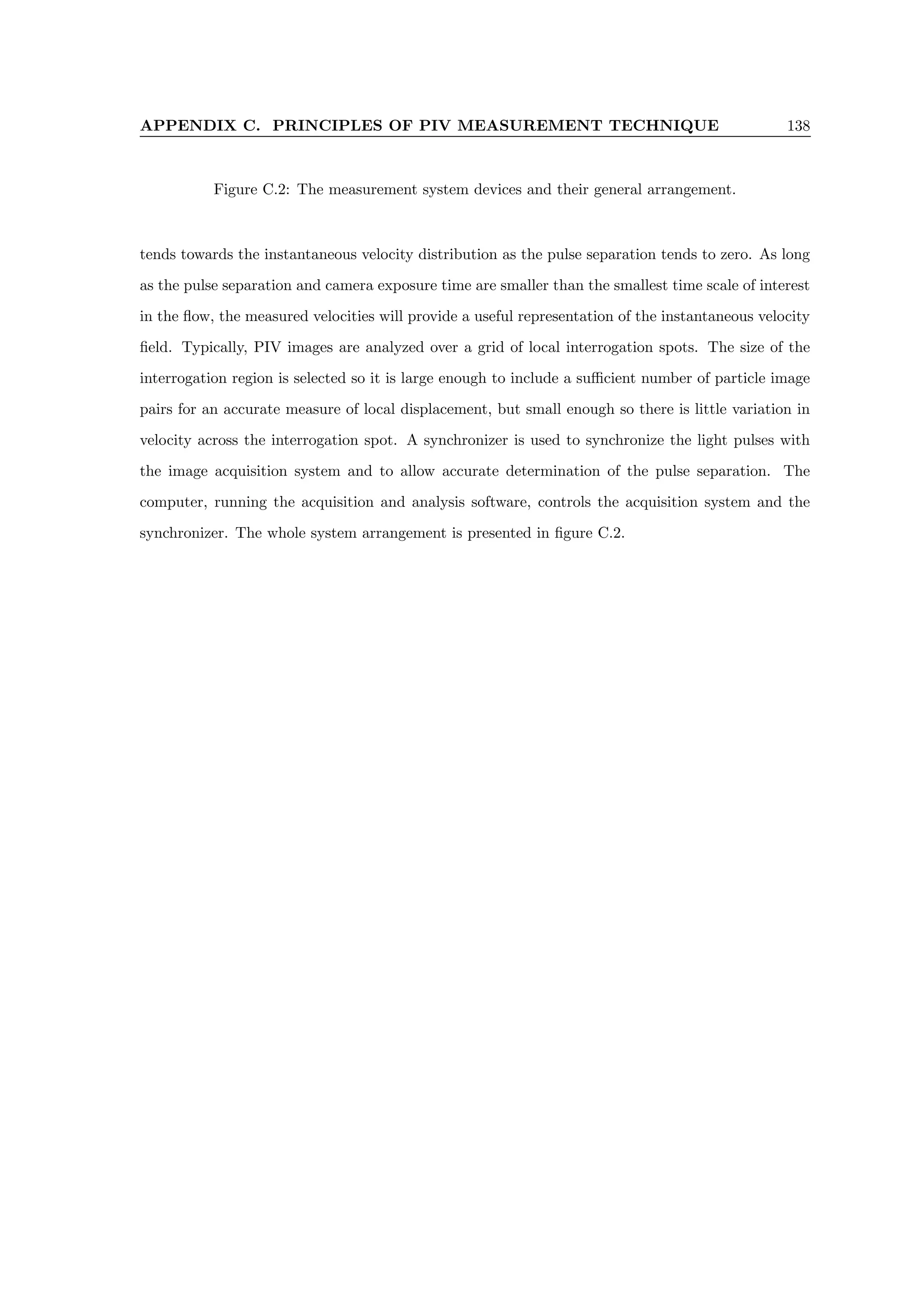

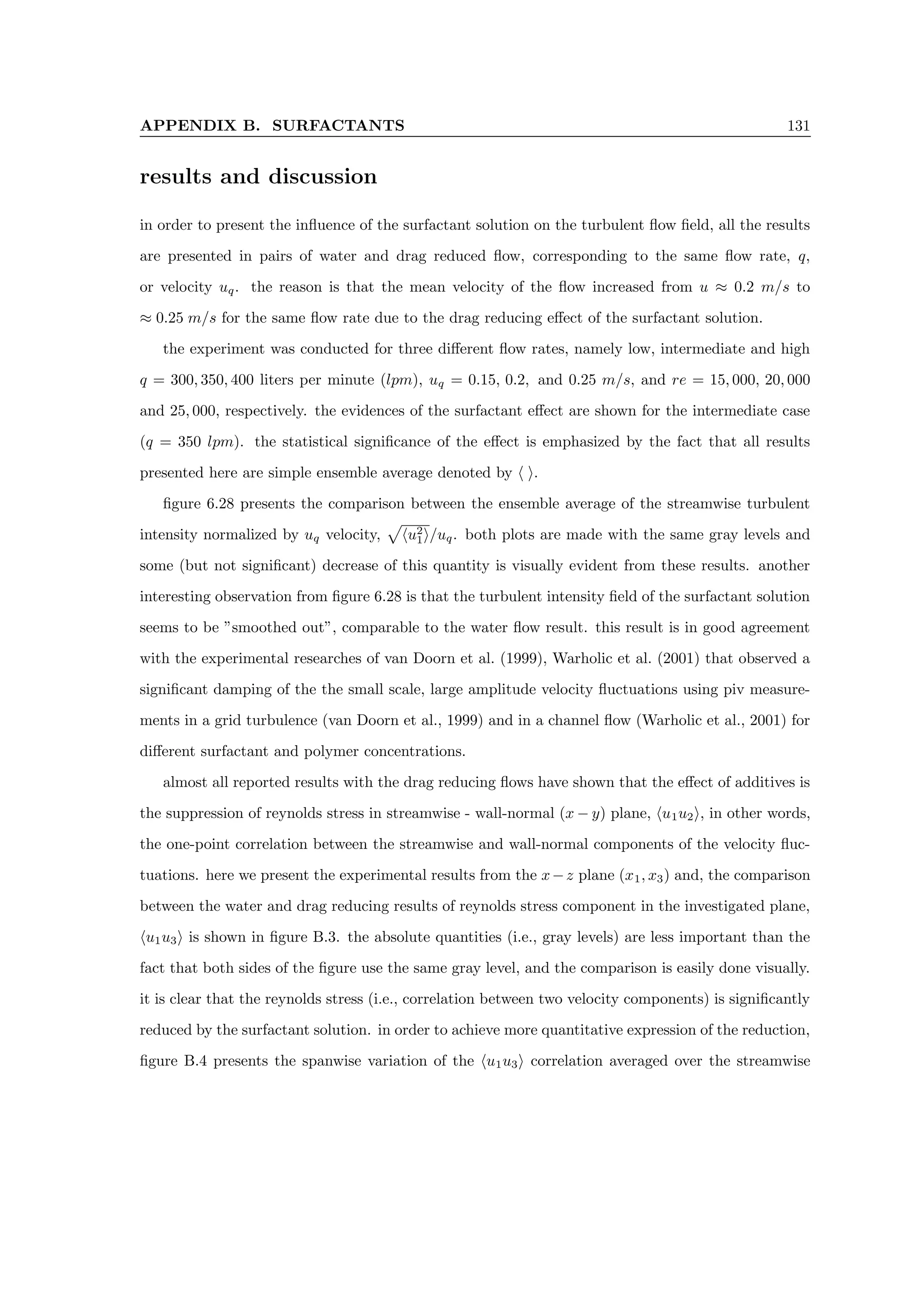

![APPENDIX B. SURFACTANTS 135

−25 −20 −15 −10 −5 0 5 10 15 20 25

−4

−3

−2

−1

0

1

2

3

4

5

x 10

−4

Z [mm]

Reynolds

stress

〈u

1

u

3

〉

Water

Agrimul 20 ppm

Figure B.4: streamwise average of the hu1u3i correlation for the water (solid line) and surfactant

solution (star-marked line).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alexliberzonphdthesisweb-240511095654-b7f38227/75/Coherent-structures-characterization-in-turbulent-flow-147-2048.jpg)