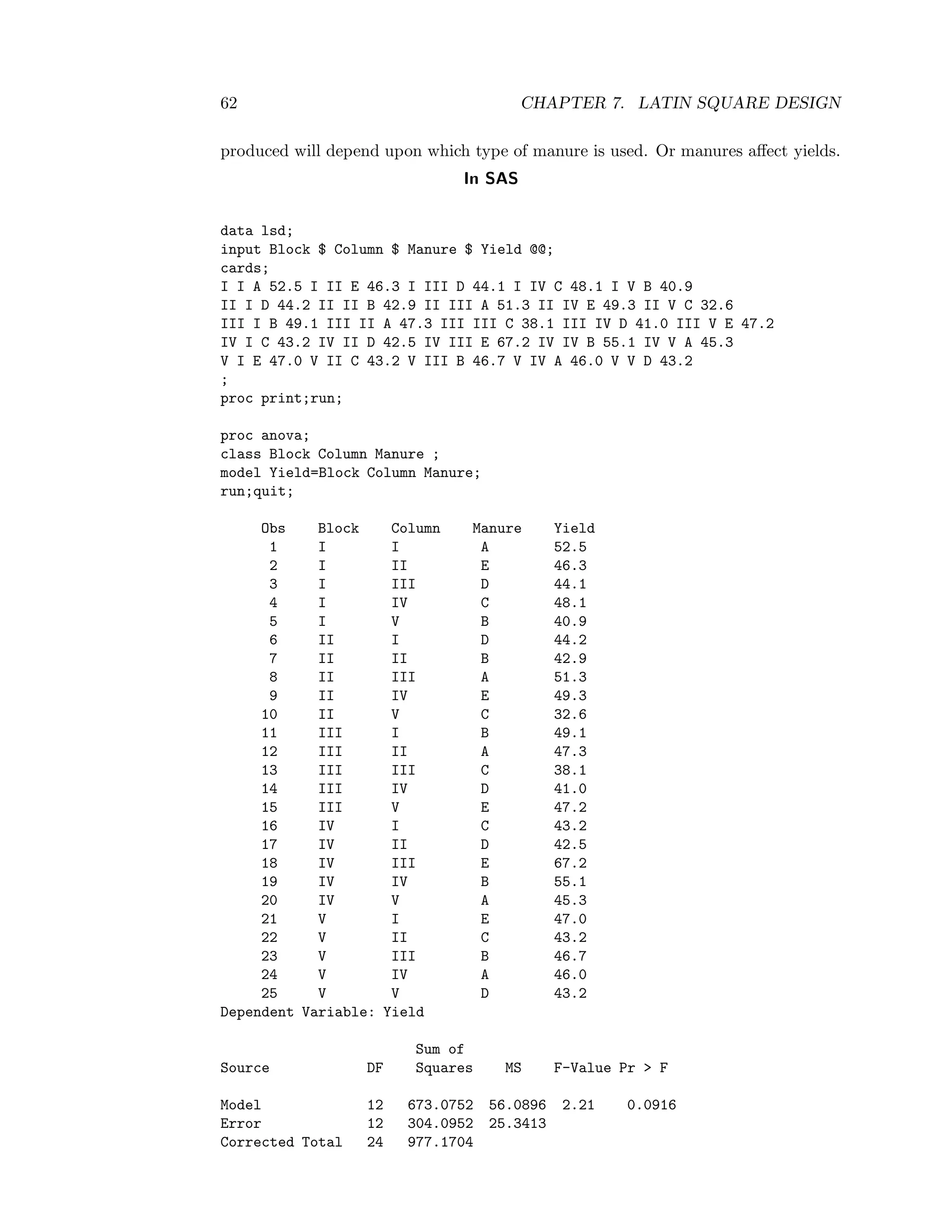

This document contains lecture notes for MTH 201: Biometry, which focuses on statistical techniques for problems in agricultural, environmental, and biological sciences. It covers topics like principles of experimental design, analysis of variance (ANOVA) for one-way and two-way classification, completely randomized design, randomized block design, Latin square design, factorial experiments, multiple comparisons, simple linear regression, correlation analysis, data transformation, and analysis of frequency data. The course aims to teach students how to design experiments and analyze and interpret results.

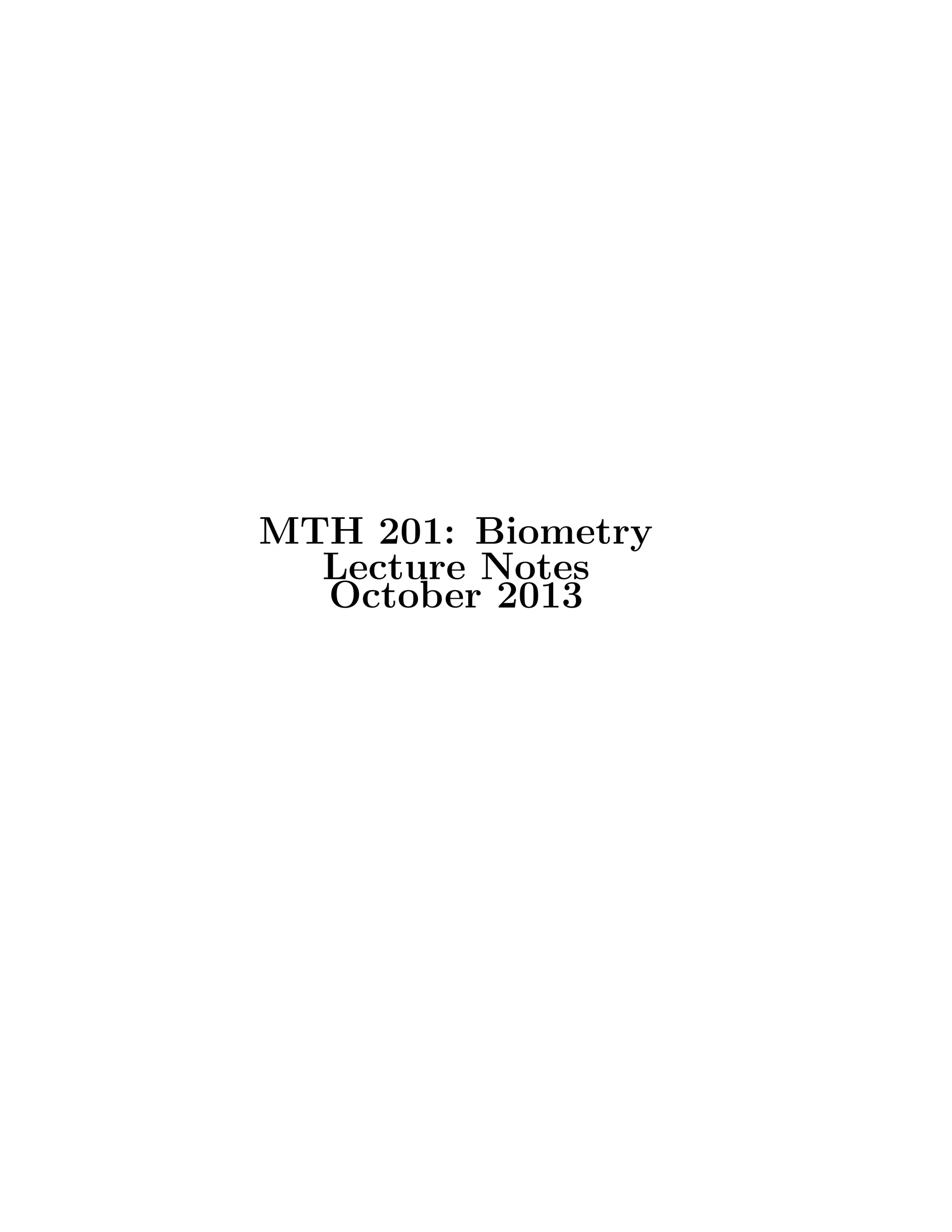

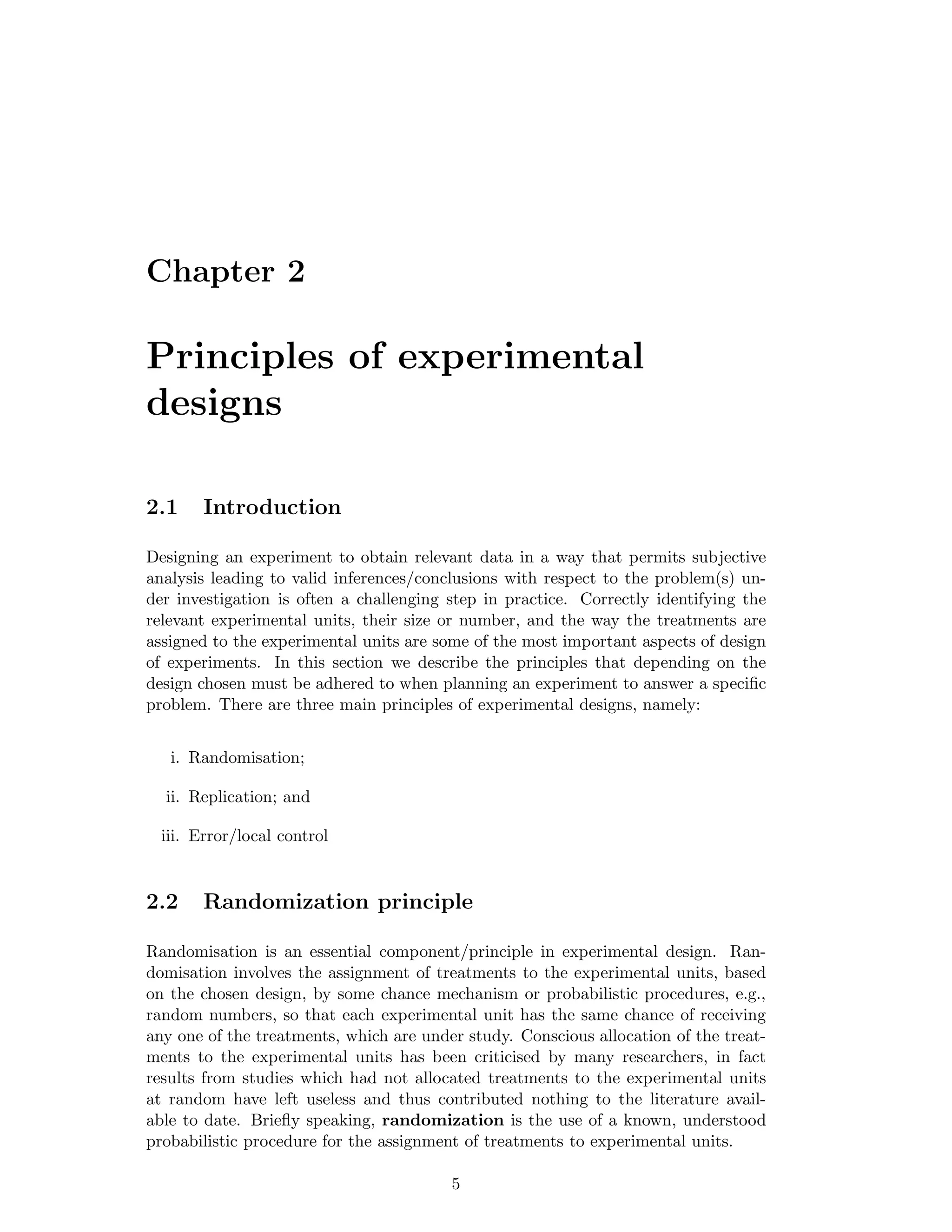

![14 CHAPTER 3. ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE

Y i.and Y .. as defined in Section 3.3.1

Thus, SST=

k

i=1

ni

j=1

Yij − Y..

2

, SSA=

k

i=1

ni

¯Yi. − ¯Y..

2

and SSE=

k

i=1

ni

j=1

Yij − ¯Yi.

2

For calculation we express the SSs as follows:

Define C.F=Correction factor =

k

i=1

ni

j=1

Yij

2

k

i=1

ni

= G2

N Here, G is the grand total=

k

i=1

ni

j=1

Yij and N as defined in Section 2.3.1

It can be shown that:

SST=

k

i=1

ni

j=

Y 2

ij −

k

i=1

ni

j=1

Yij

2

k

i=1

ni

or

k

i=1

ni

j=

Y 2

ij − G2

N or

k

i=1

ni

j=

Y 2

ij − C.F

Treatment SS or Factor A SS=

k

i=1

Y 2

i

ni

− C.F

Where: Yi =

ni

j=1

Yijis the total yield of all the njplots which carried treatment i

Error SS (SSE) =SST-SSA

Since we have k levels of factor (A) or treatment then SSA will have k-1 independent

comparisons possible (degrees of freedom). Similarly SST will have N-1 independent

comparisons (degrees of freedom), and SSE will have (N-1)-(k-1) =N−k independent

comparisons (degrees of freedom).

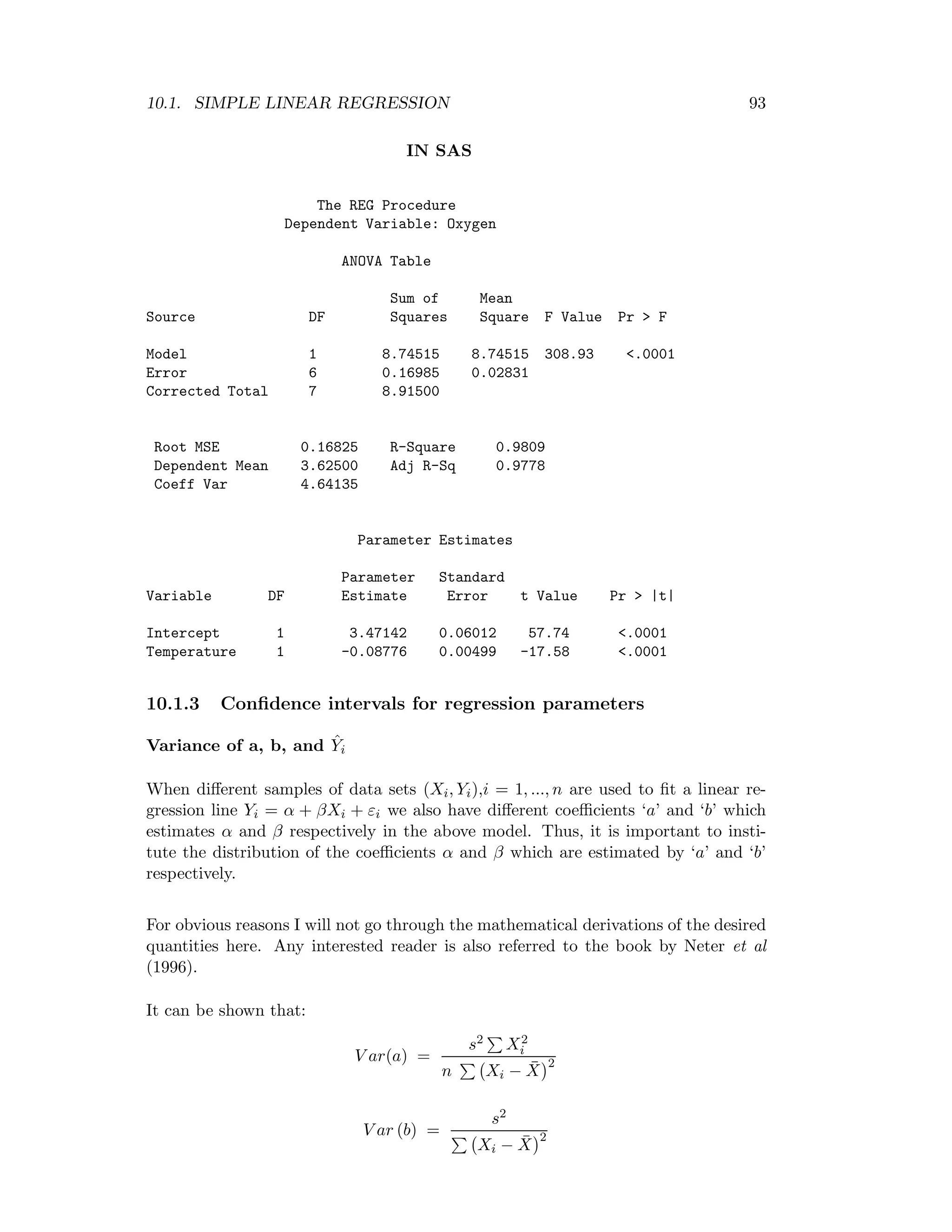

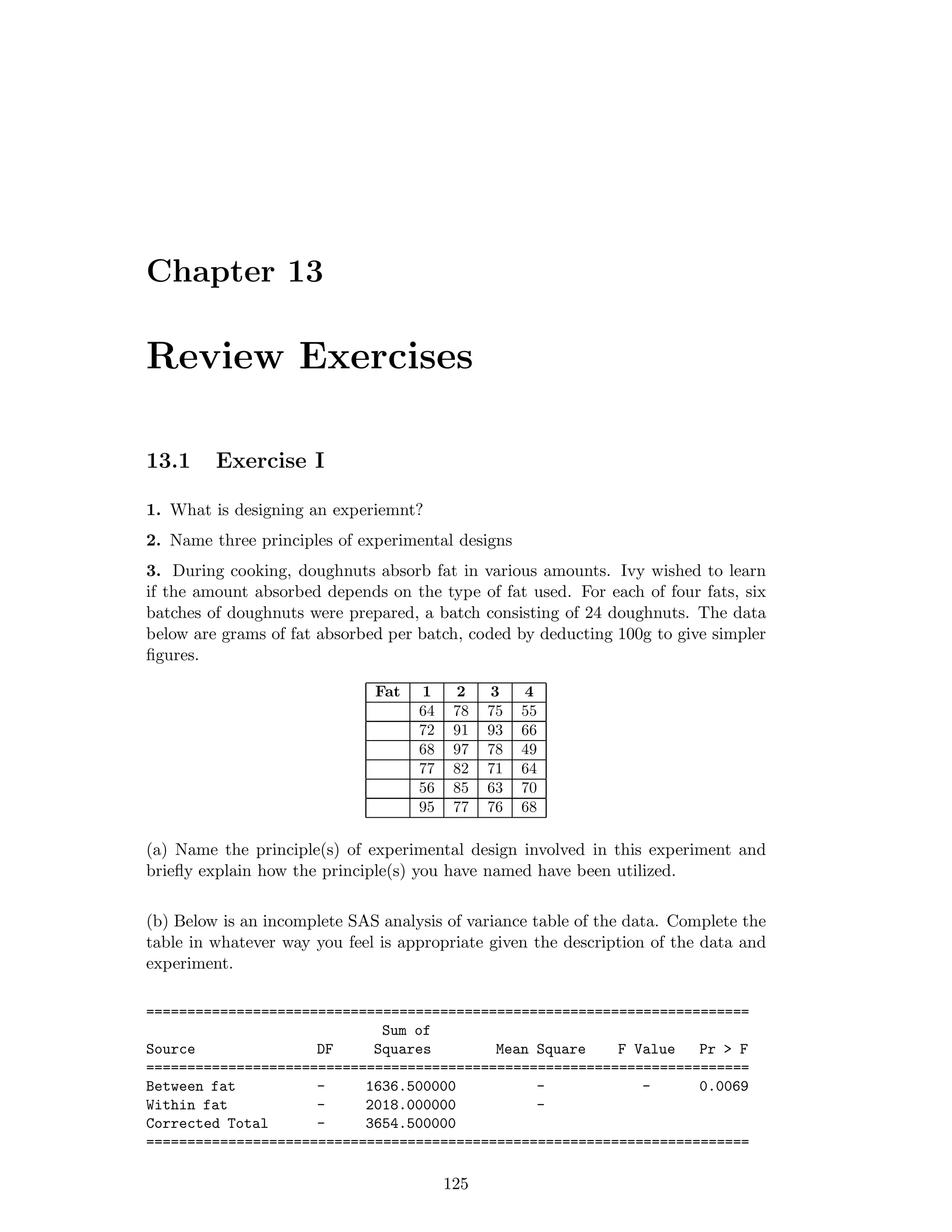

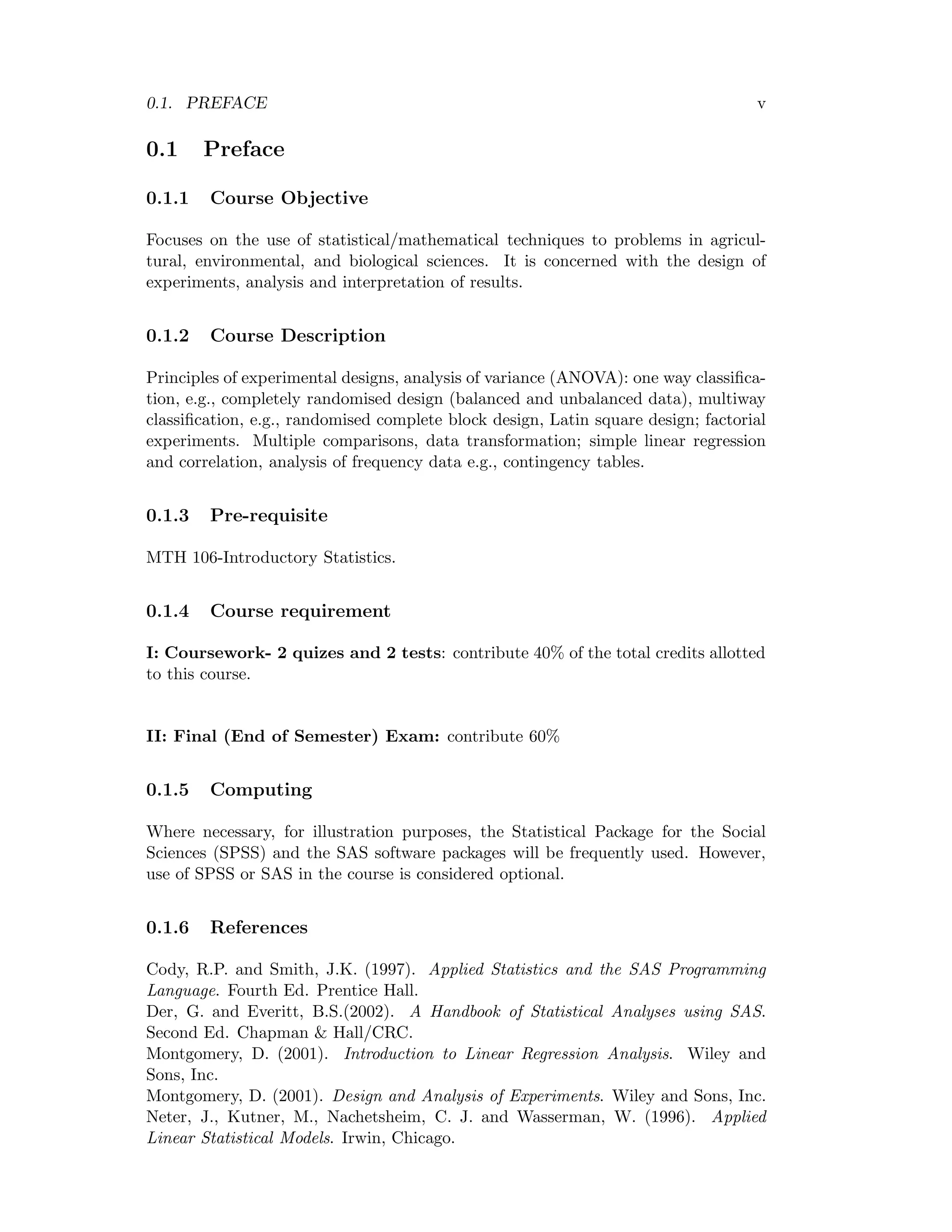

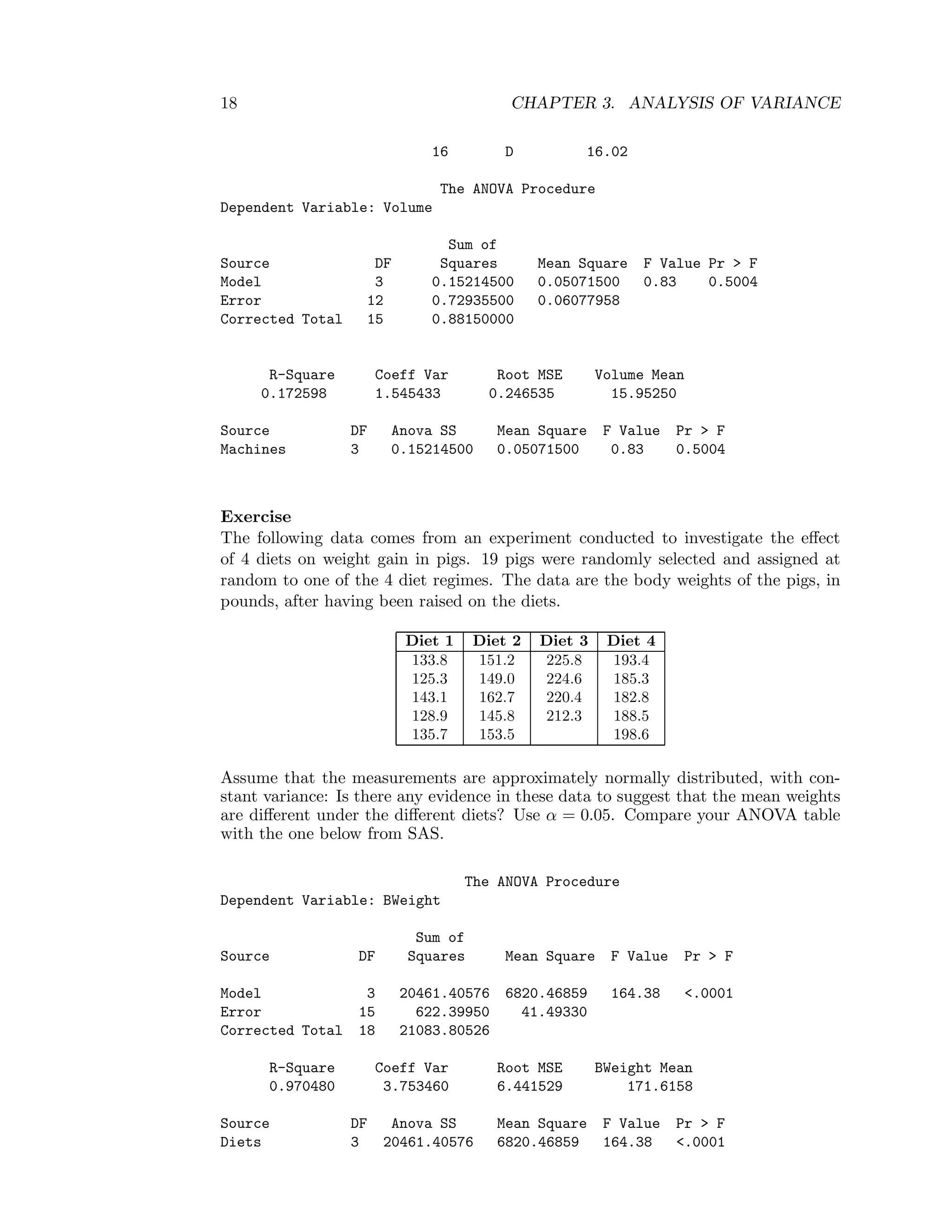

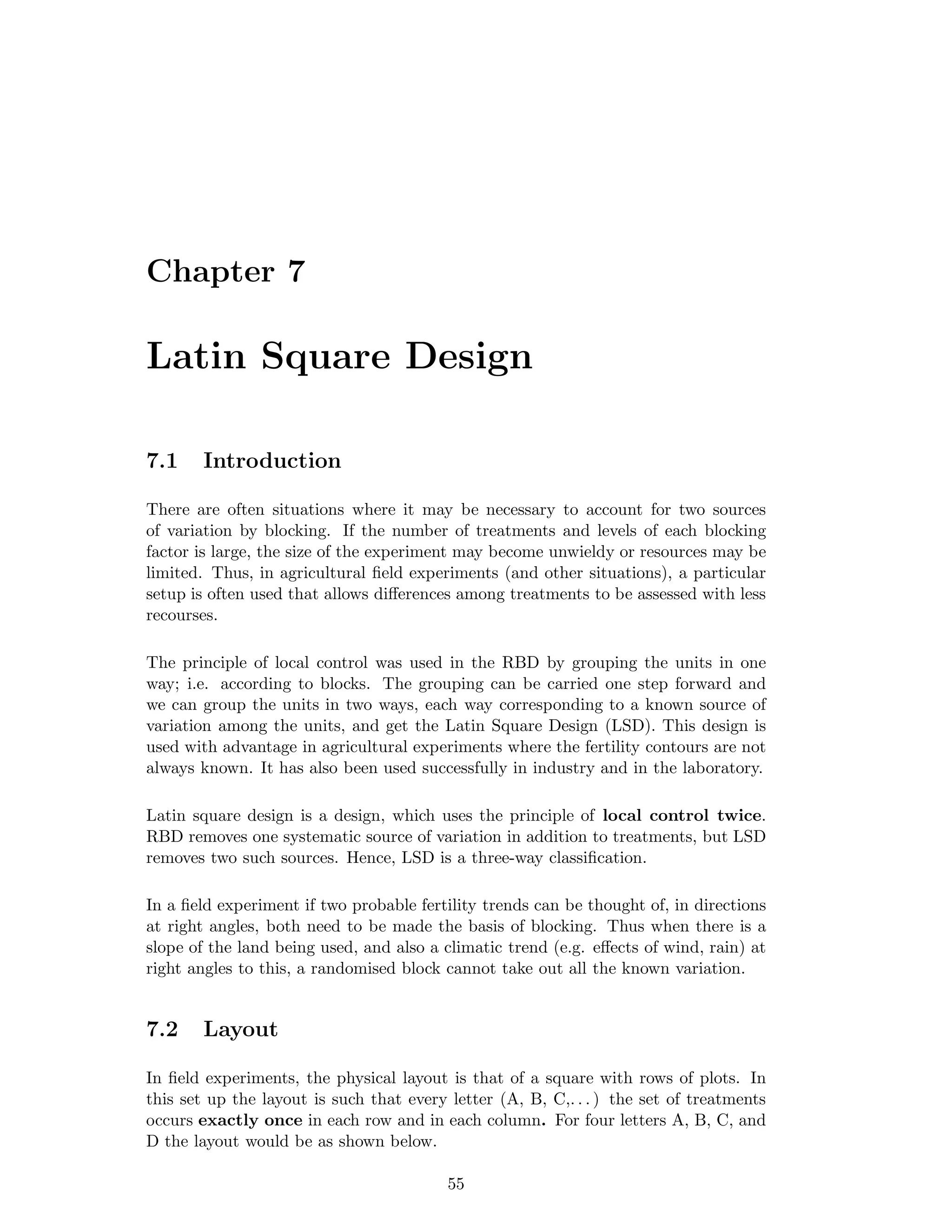

We summarize the computations in a table known as the ANOVA table.

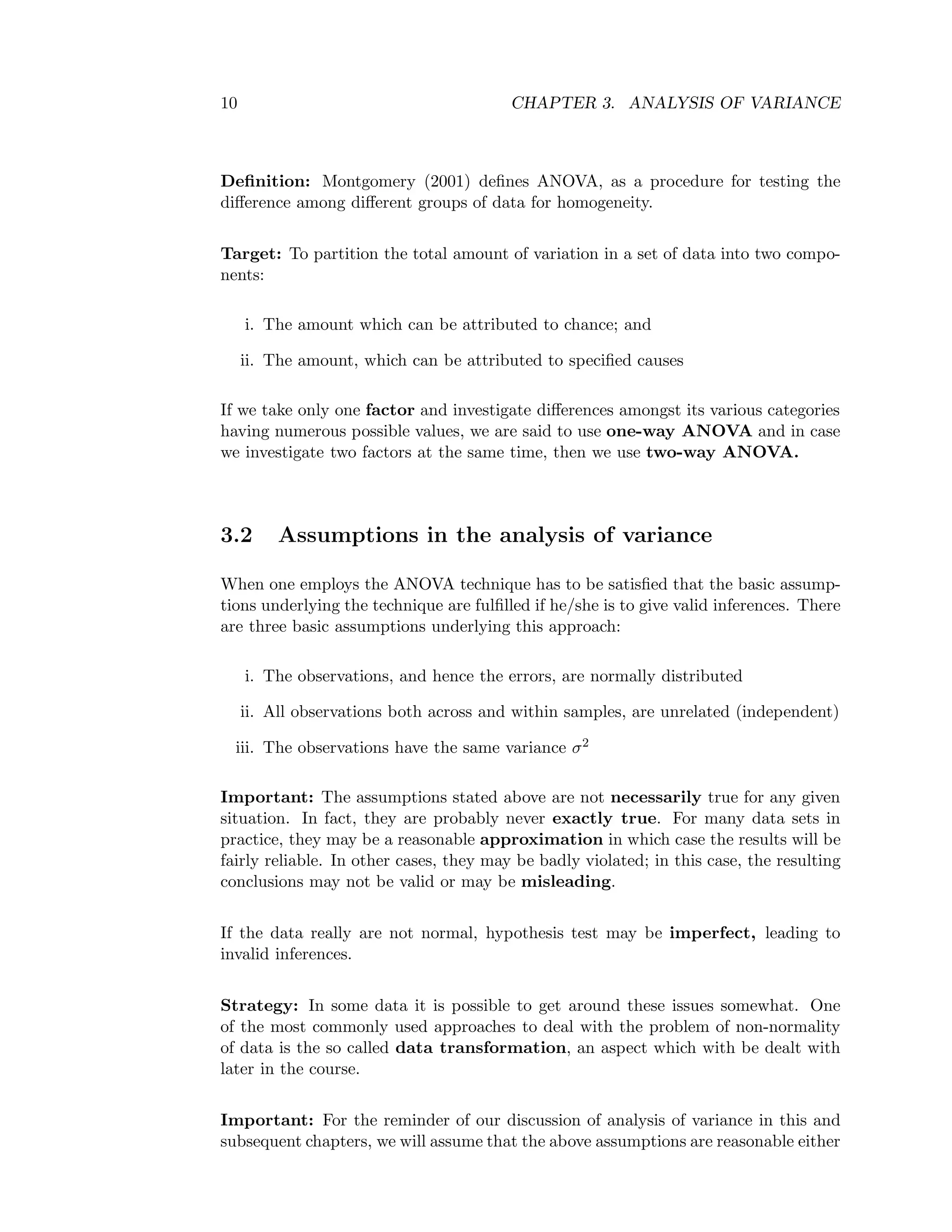

Table 3.1: One way ANOVA table with unequal replication

Source of Degrees of Sum of Mean square

variation (S.V) freedom (D.F) squares (S.S) (M.S) F- ratio

Between treatments k-1 SSA SSA

K−1 = MSA MSA

MSE

Error(within treat.) N − k SSE SSE

N−k = MSE

Total N-1 SST

The calculated F-value MSA

MSE is compared with the F-tabulated value

(Fα, [(k − 1) , (N − k)]) at α level of significance for k-1 and N −k degrees of freedom.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-21-2048.jpg)

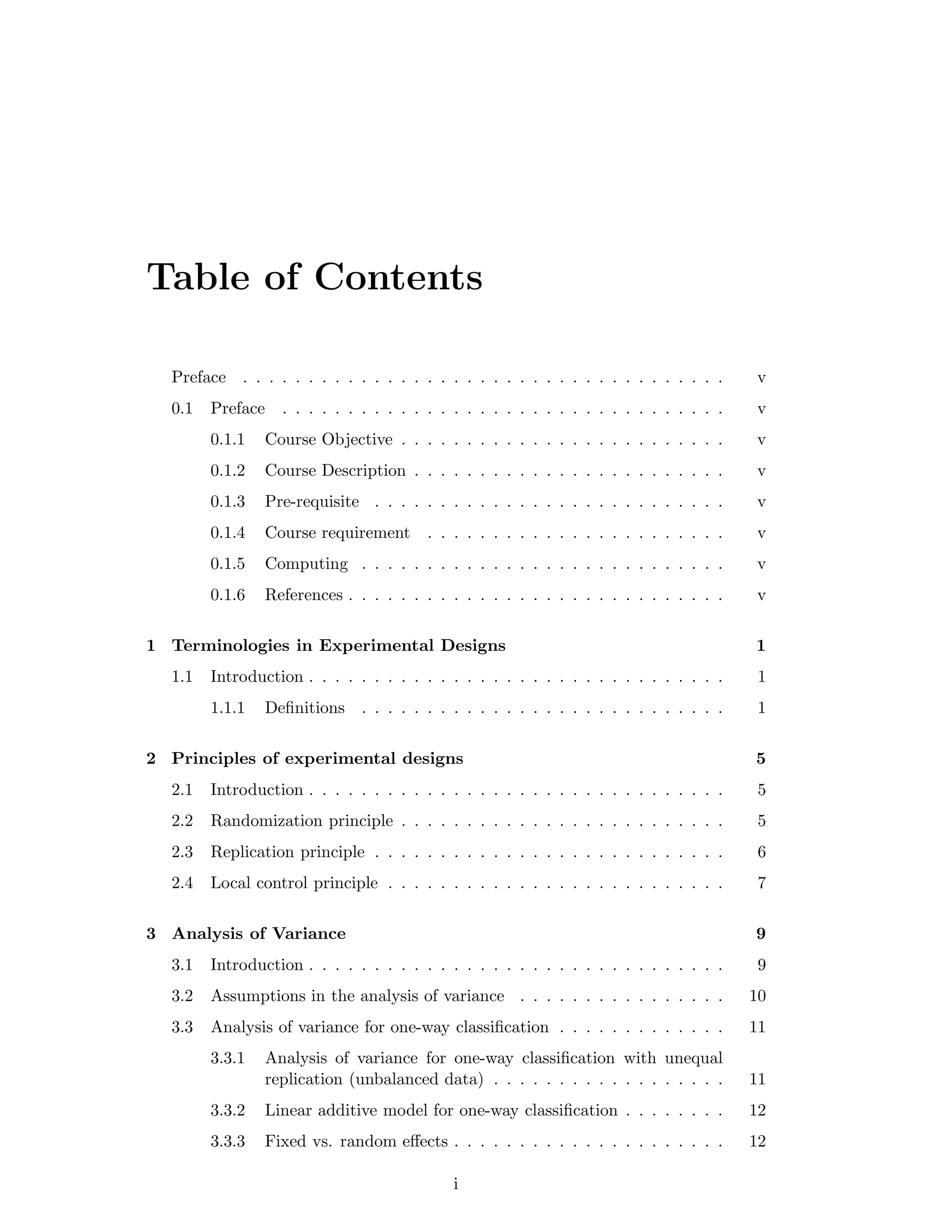

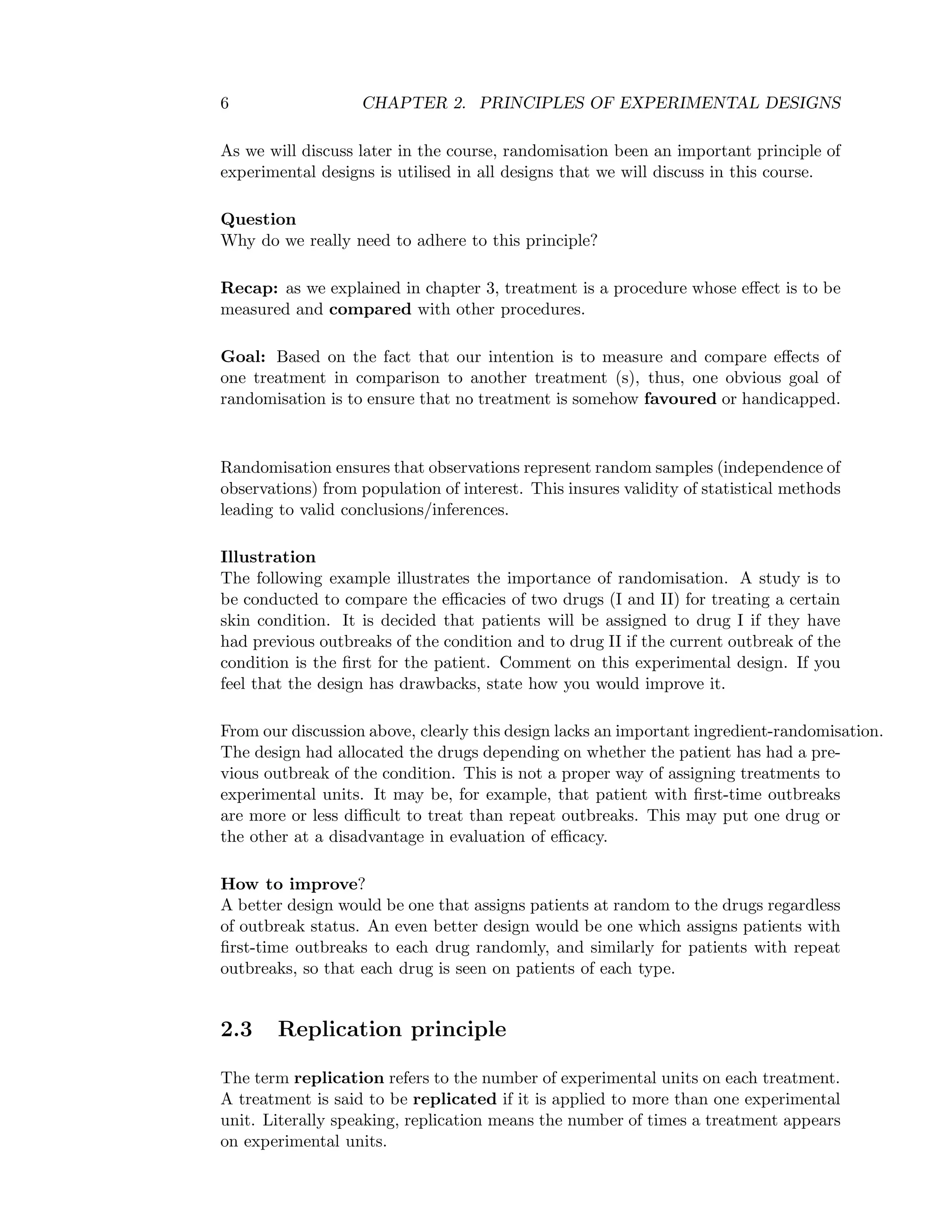

![3.3. ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE FOR ONE-WAY CLASSIFICATION 15

Statistical Hypotheses

The question of interest in this setting is to determine if the means of the different

treatment populations are different.

Mathematically we write:

Ho : µ1 = µ2 = ... = µk That is, the µi are all equal

H1 : µi = µj for at least one i = j That is, the µi are not all equal

Or simply

Ho :There is no variation among the treatments

H1 :Variation exists

Test procedure

At level of significance α, if F> Fα, [(k − 1) , (N − k)] then there is evidence for no

significance variation (i.e. we reject the null hypothesis).

Note that the alternative hypothesis stated above does not specify the way in

which the treatment means (or deviation) differ. The best we can say based on our

statistic is that they differ somehow.

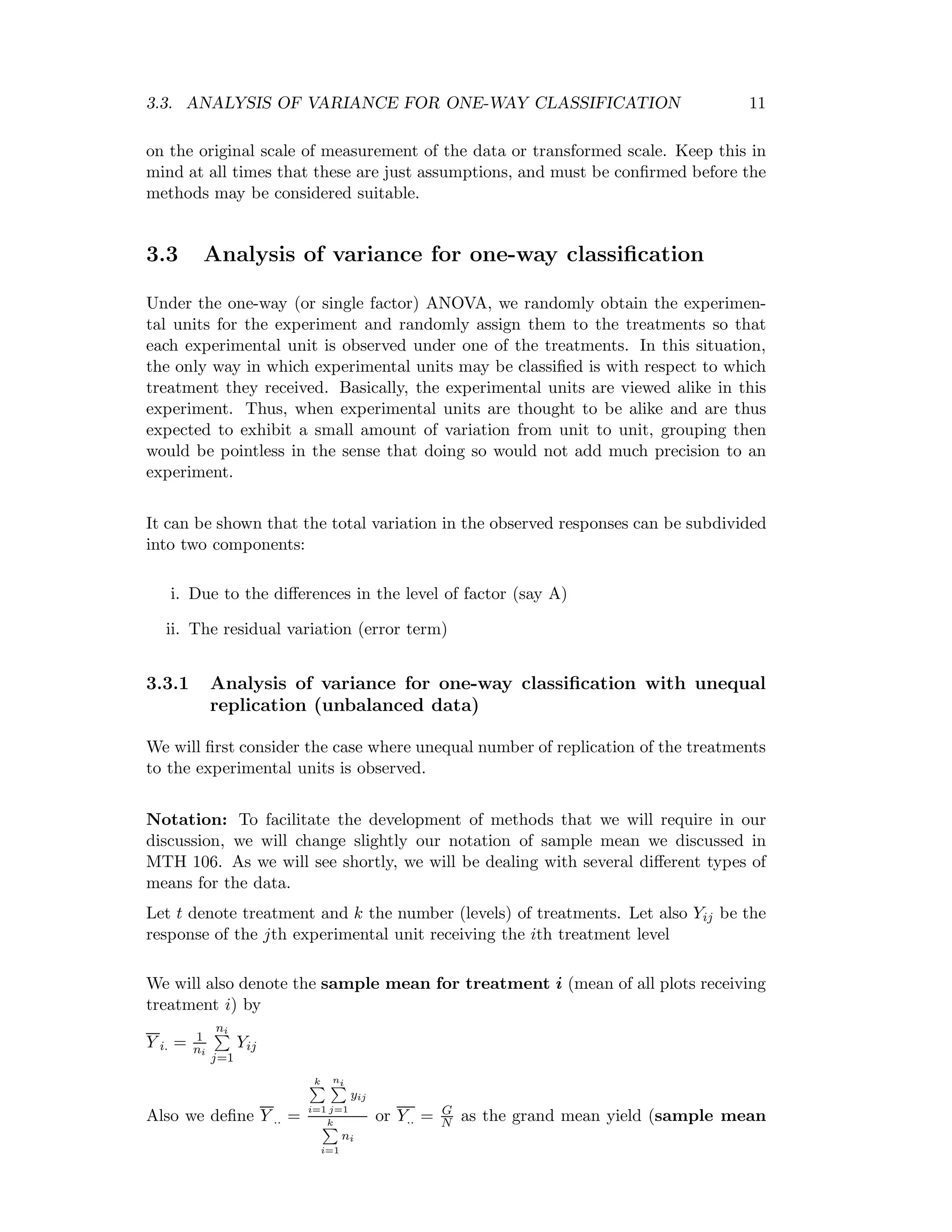

Example

Four Machines are used for filling plastic bottles with a net volume of 16.0 cm3.

The quality-engineering department suspects that both machines fill to the same net

volume whether or not this volume is 16.0 cm3. A random sample is taken from the

output of each machine.

Table 3.2: Machine data set

Machines

A B C D

16.03 16.01 16.02 16.03

16.04 15.99 15.97 16.04

15.96 16.03 15.96 16.00

16.05 15.05 16.02

16.04

Total 64.08 48.03 79.04 64.09

Assume that the measurements are approximately normally distributed, with ap-

proximately constant variance σ2. Do you think the quality-engineering department

is correct? Use α = 0.05

Statistical hypotheses:

Ho :There is no significant variation among the levels of machines

H1 :Variation exists

or

Ho : µ1 = µ2 = µ3 = µ4 (all means are equal)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-22-2048.jpg)

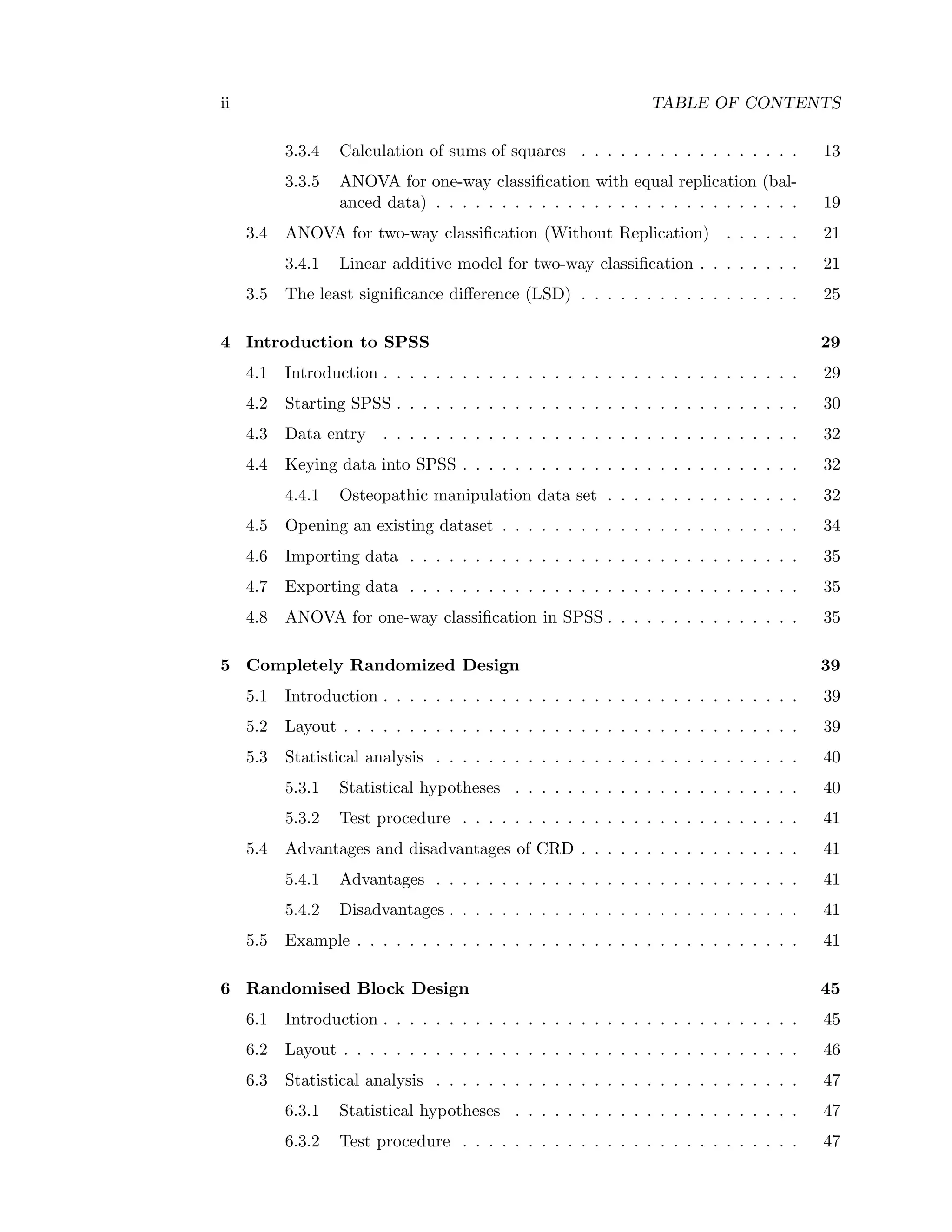

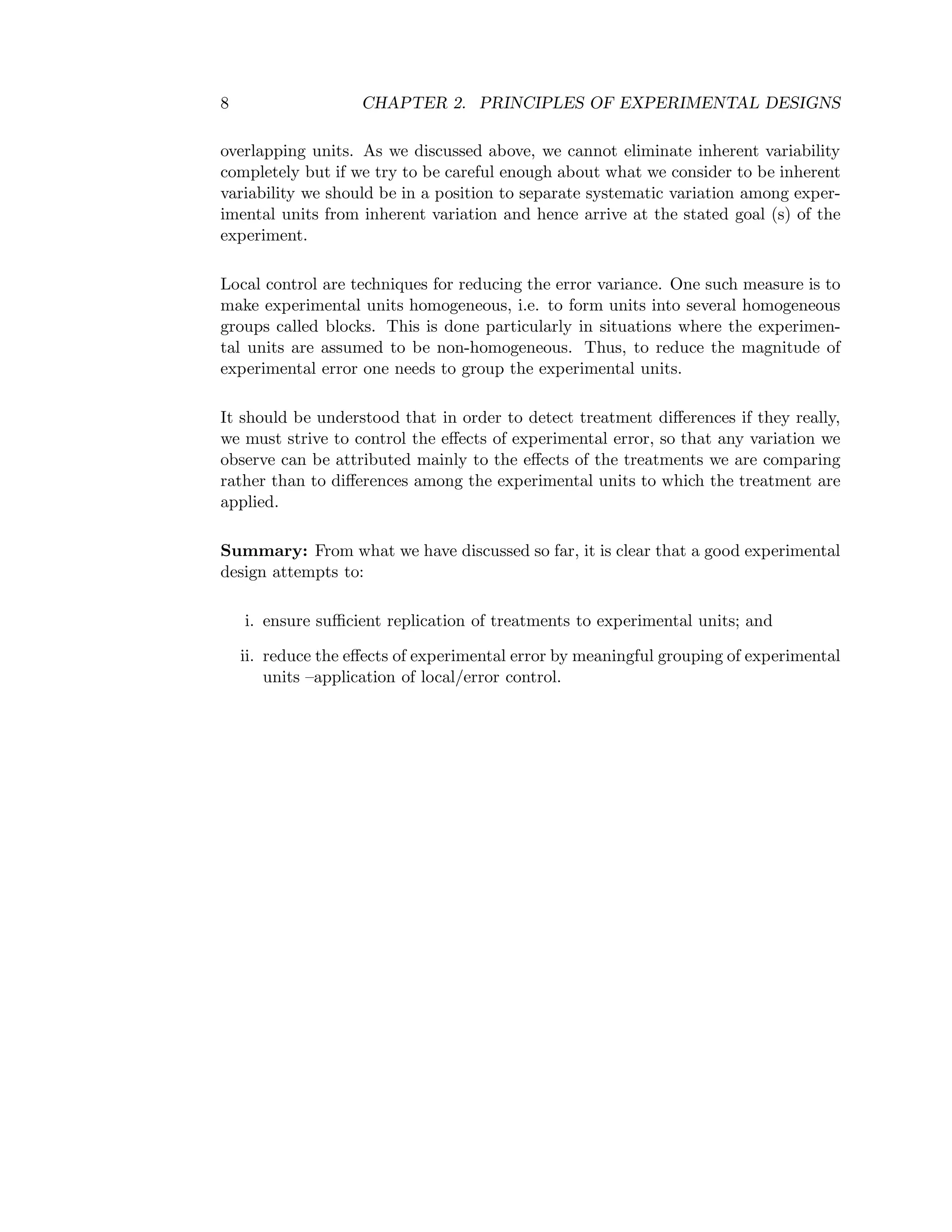

![3.3. ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE FOR ONE-WAY CLASSIFICATION 19

3.3.5 ANOVA for one-way classification with equal replication (bal-

anced data)

In the above exercise the diets 1, 2, and 4 are each replicated 5 times while diet 3 is

replicated 4 times. In this case as we have discussed above, the sample mean for

treatment i is Y i. = 1

ni

ni

j=1

Yij. We now discuss the case where ni = n for all i,

i=1, 2,. . . , k

Since each treatment is replicated the same number of time (say n), then the total

number of observations, N=nk.

Thus, with this new notation, we define the quantities Y i.,Y .., Total SS, Treatment

SS, and Error SS and their degrees of freedom as follows:

Y i. = 1

n

n

j=1

Yij, Y .. =

k

i=1

n

j=1

yij

nk orY.. = G

N , Total SS (SST) =

k

i=1

n

j=1

Y 2

ij − G2

N ,

Treatment SS or Factor A SS=

k

i=1

Y 2

i

n − C.F where C.F =

k

i=1

n

j=1

Yij

2

nk = G2

N

G = the grand total=

k

i=1

n

j=1

Yij

The degrees of freedom for Treatment SS, Error SS and Total SS, are respectively

(k-1), (N − k) or (nk-k) or k(n-1) and (N-1) or (nk-1).

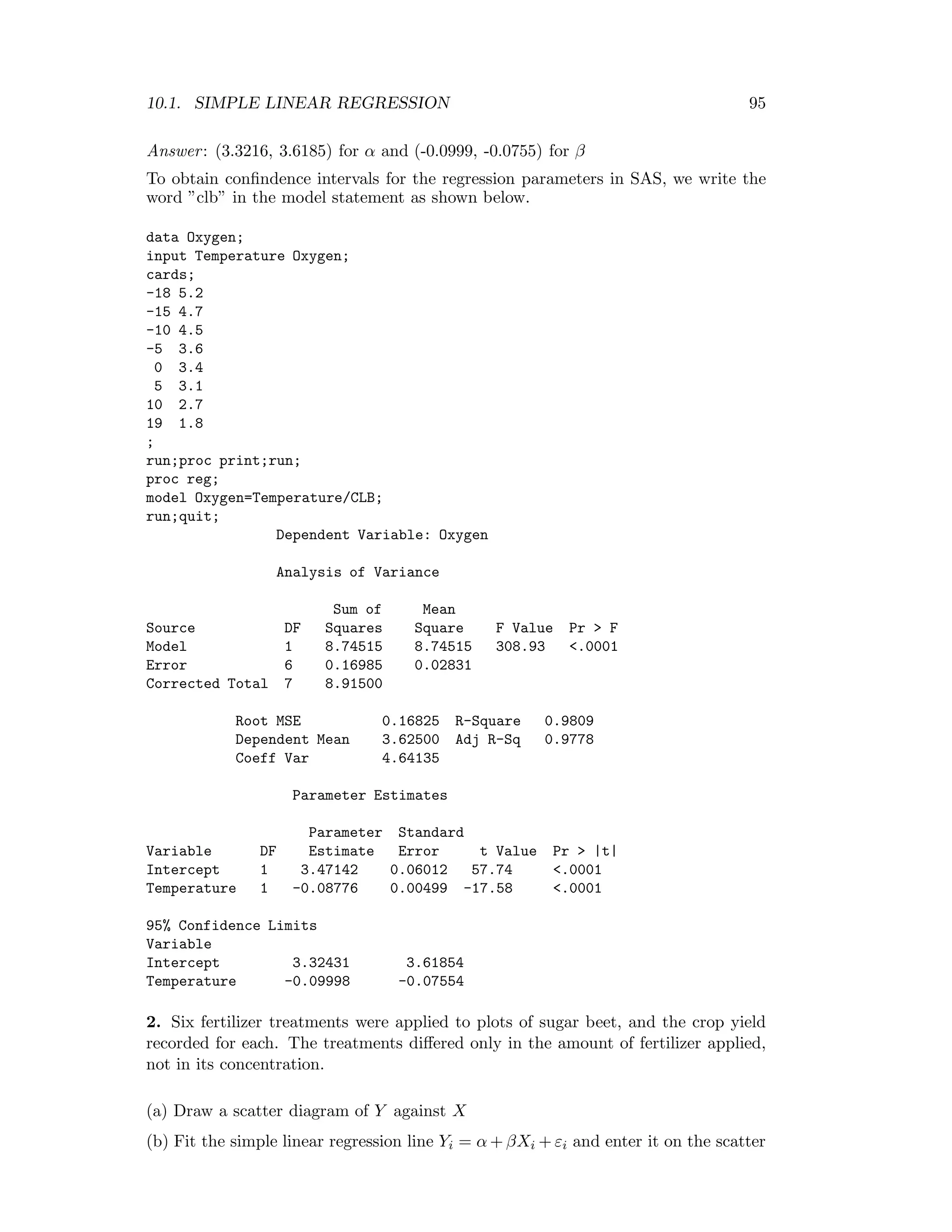

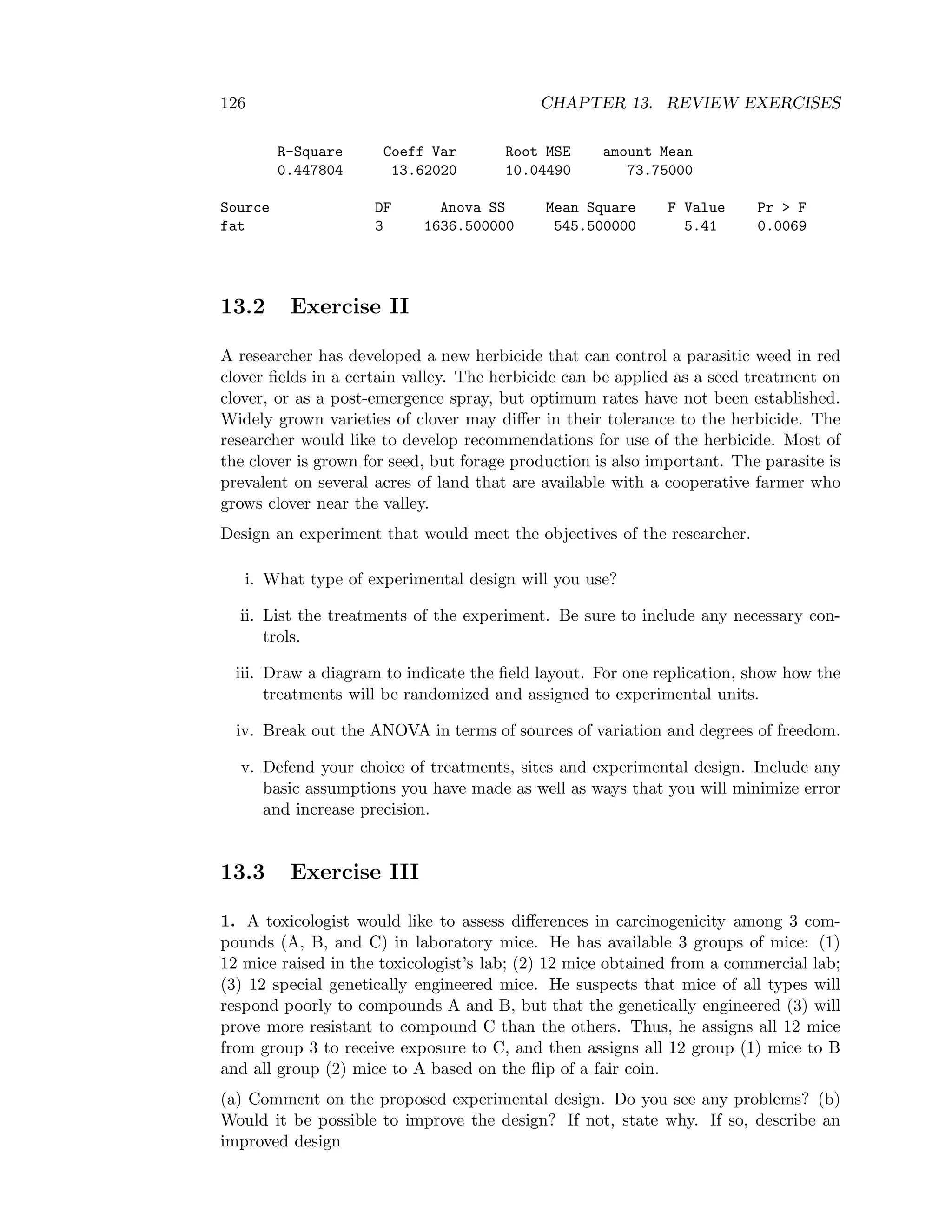

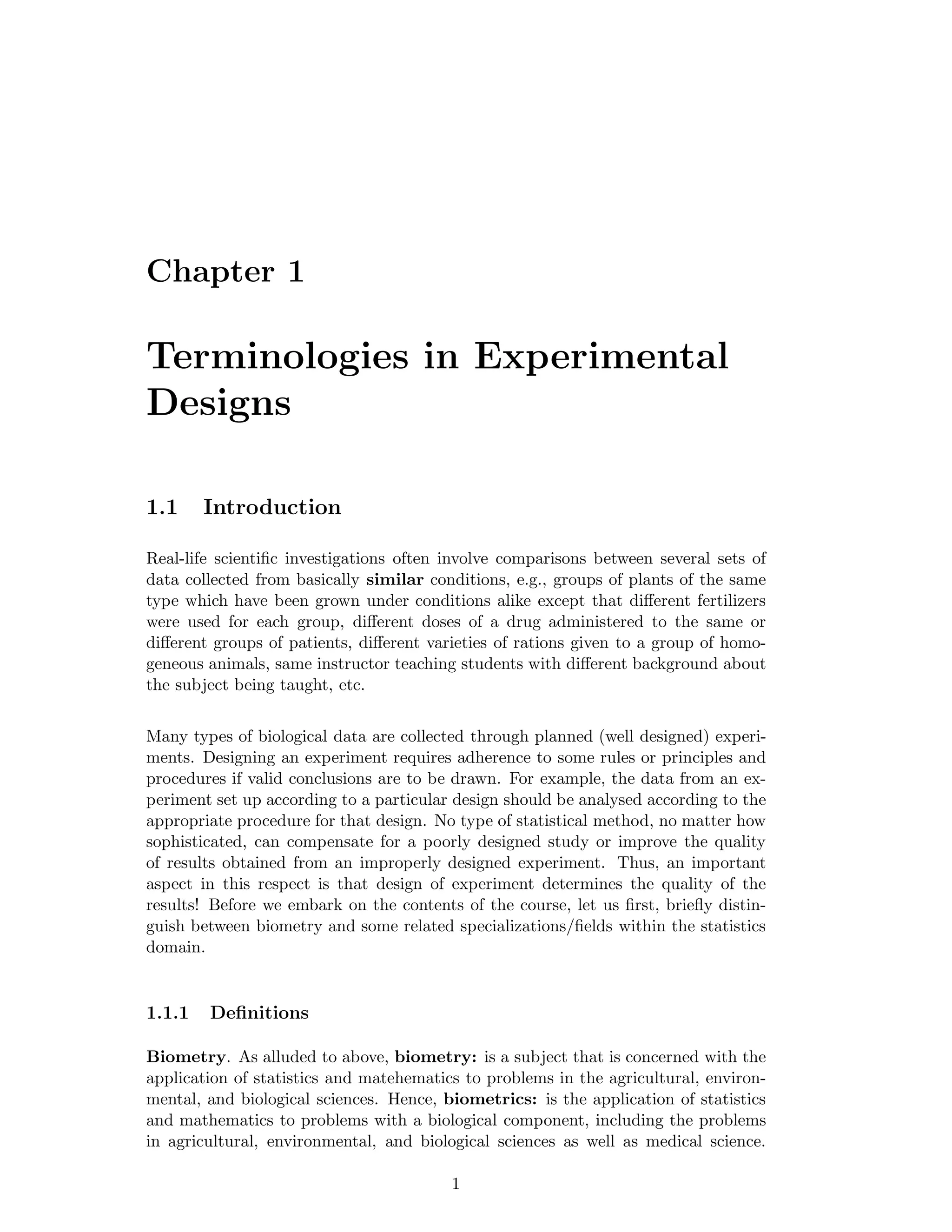

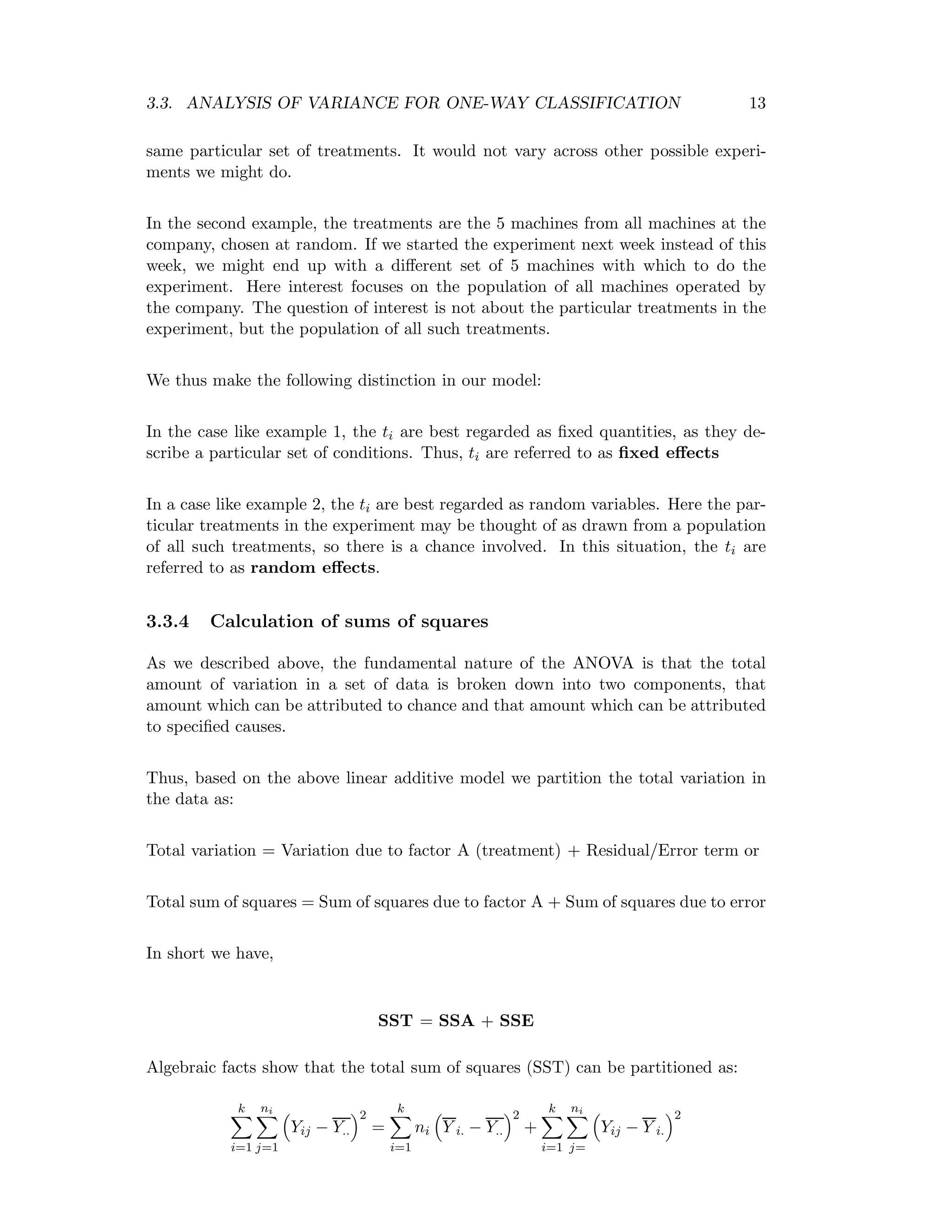

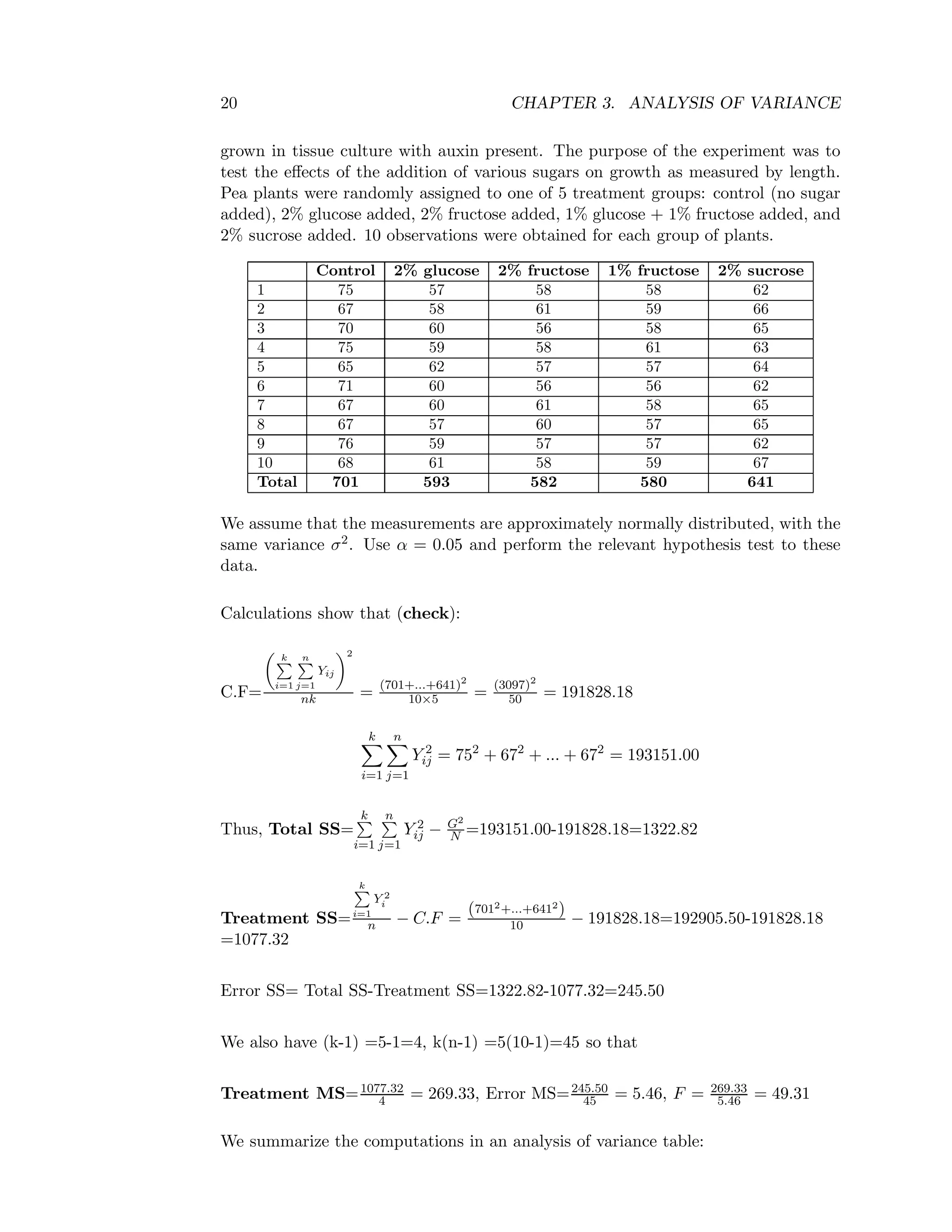

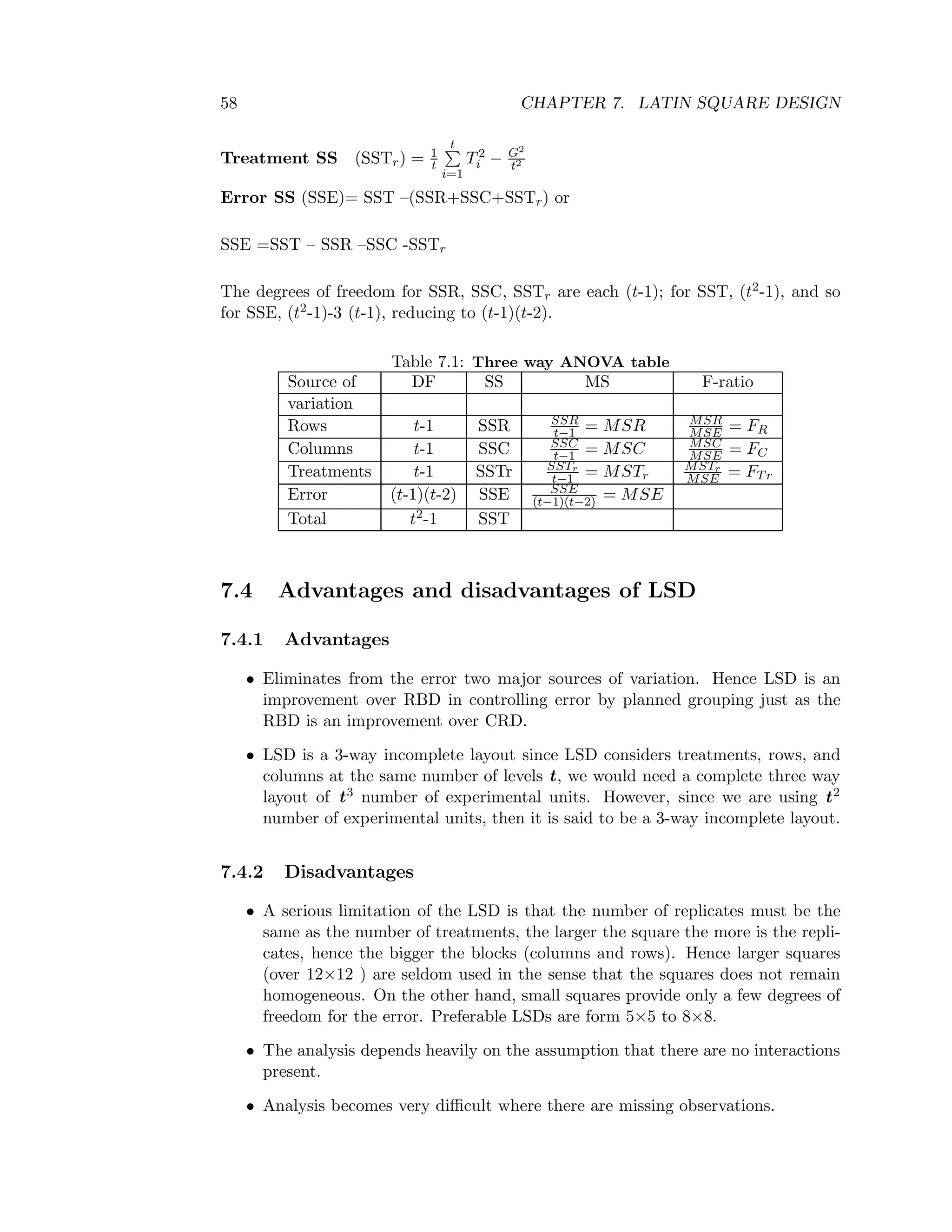

Table 3.4: One way ANOVA table with equal replication

Source of DF SS MS F- ratio

variation

Between treat. k-1 SSA SSA

k−1 = MSA MSA

MSE

Error (within treat.) k(n-1) SSE SSE

k(n−1) = MSE

Total N-1 SST

The calculated F-value MSA

MSE is compared with the F-tabulated value

(Fα, [(k − 1) , (k(n − 1))]) at α level of significance for k-1 and k(n-1) degrees of free-

dom.

Statistical Hypotheses as given above

Test procedure

At level of significanceα, if F> Fα, [(k − 1) , (k(n − 1))] then there is evidence for no

significance variation (i.e. we reject the null hypothesis).

Example

The following data record the length of pea sections, in ocular units (×0.114 mm),](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-26-2048.jpg)

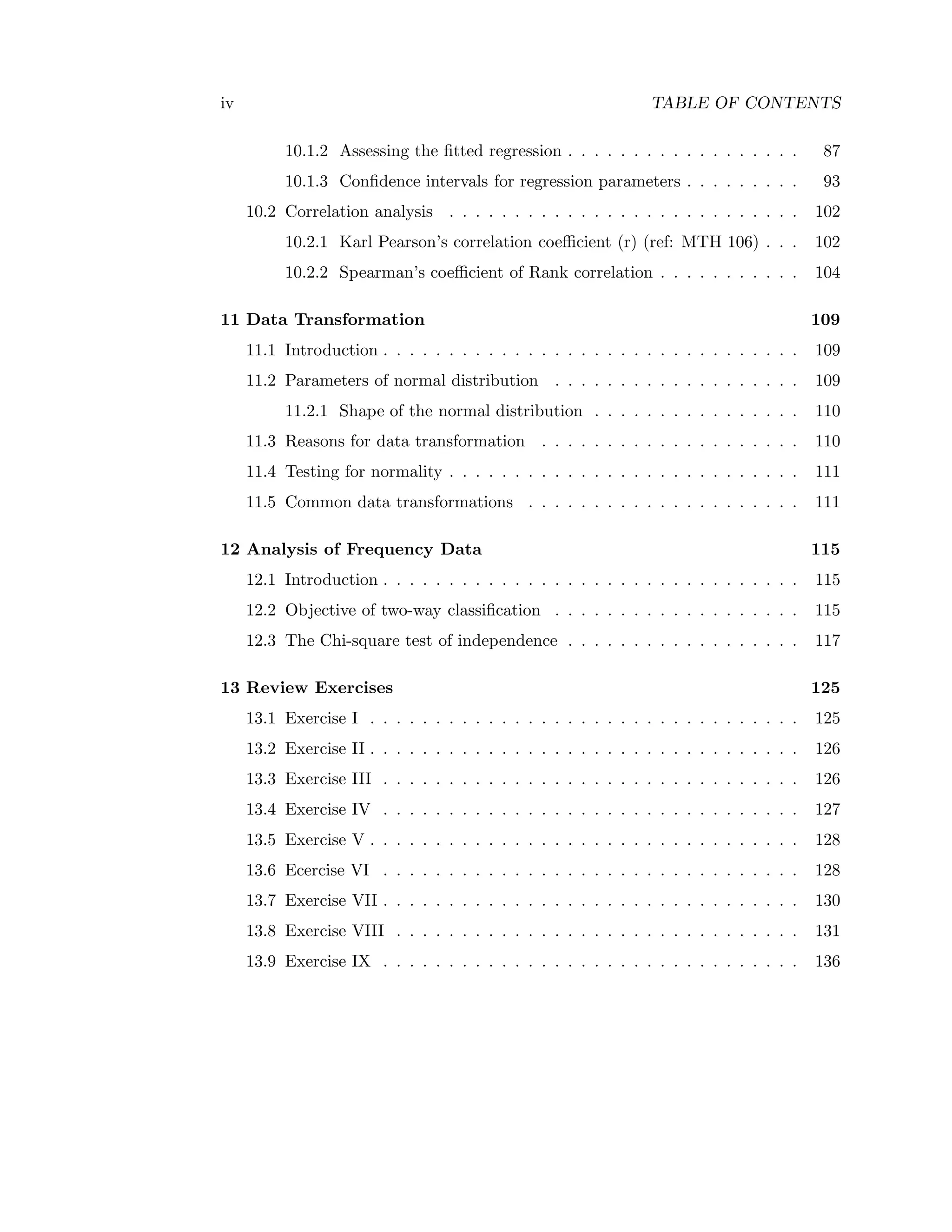

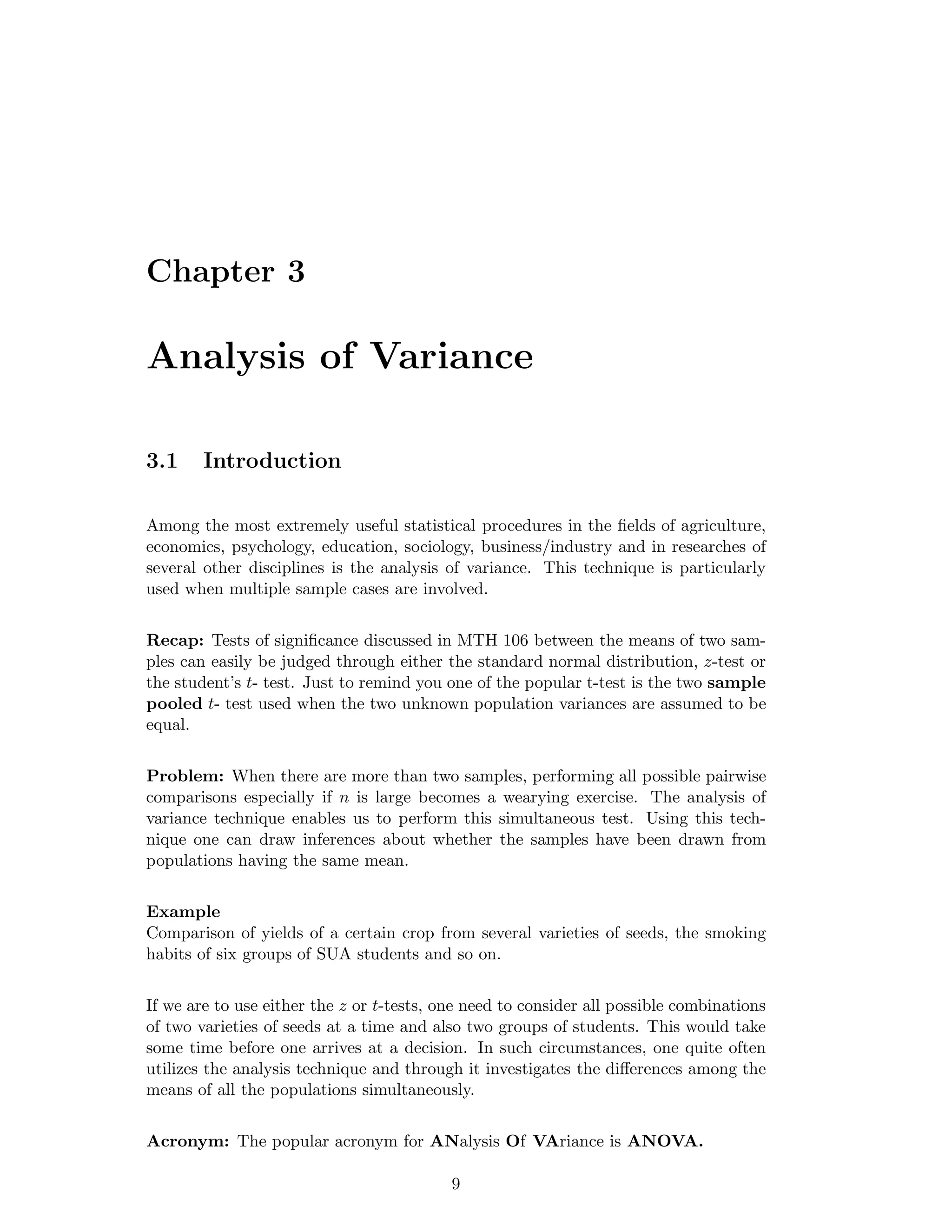

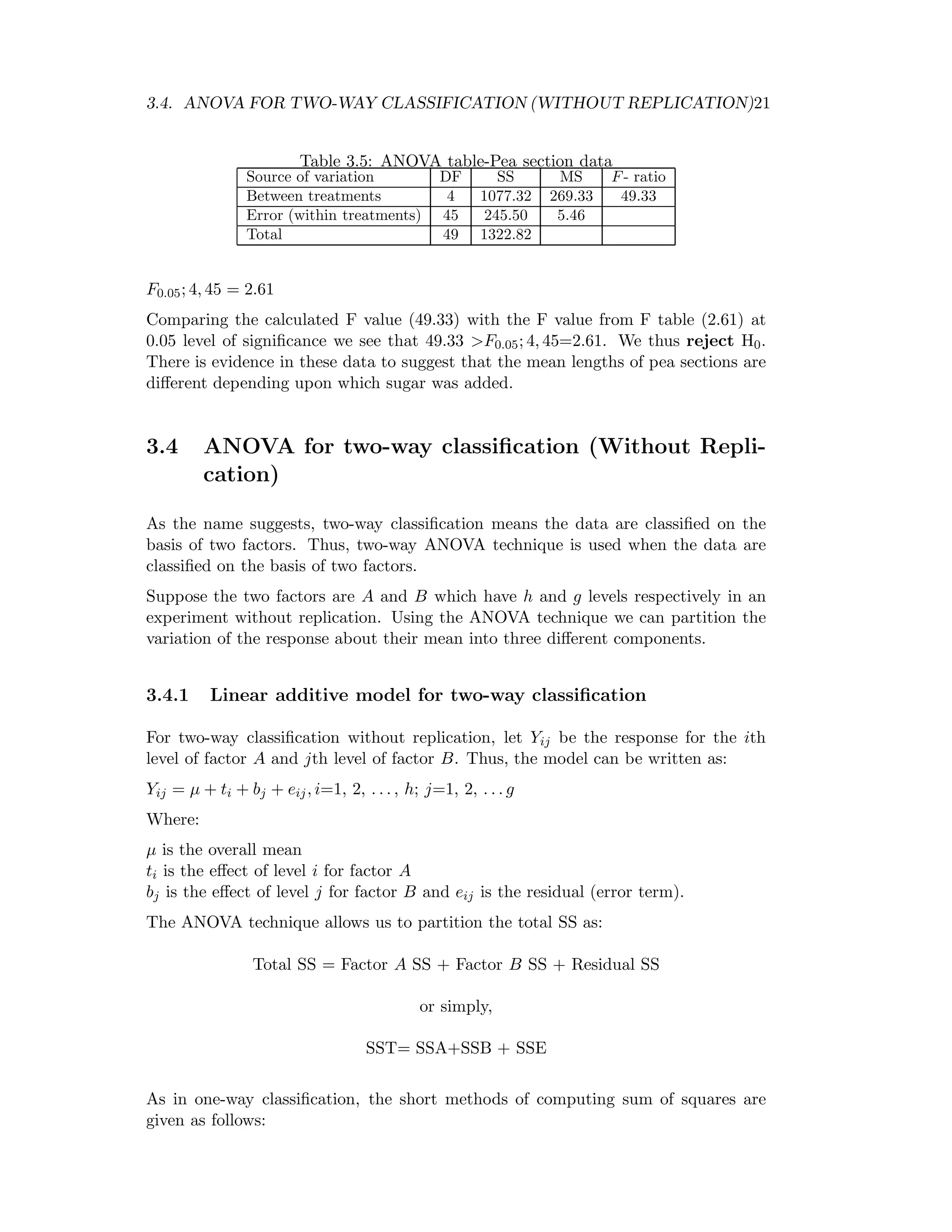

![22 CHAPTER 3. ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE

Let N (=hg) be the total number of experimental observations

Let G = the sum of yields over all the N (=hg) plots. So that G =

h

i=1

g

j=

Yij,

Correction factor (C.F) =G2

N =

h

i=1

g

j=1

Yij

2

hg

Total SS (SST) =

h

i=1

g

j=1

Y 2

ij − C.F

Factor A SS (SSA) =1

g

h

i=1

Y 2

i − C.F where Yi =

g

j=1

Yij is the total yield of all the

g plots which carried treatment i.

Factor B SS (SSB) =1

h

g

j=1

Y 2

j − C.F where Yj =

h

i=1

Yij is the total yield of all

the h plots which carried treatment j.

Error SS (SSE) = SST – (SSA +SSB)= SST –SSA- SSB

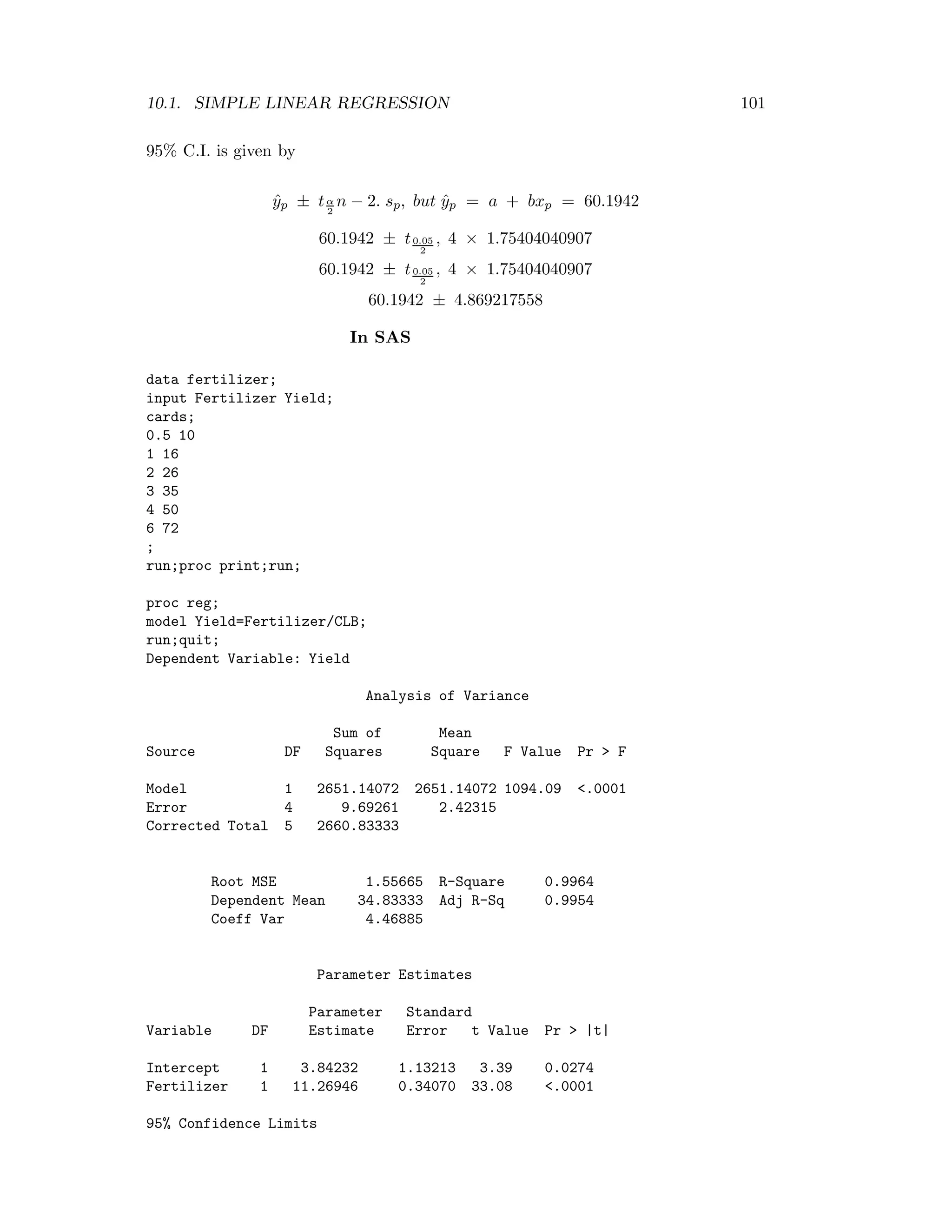

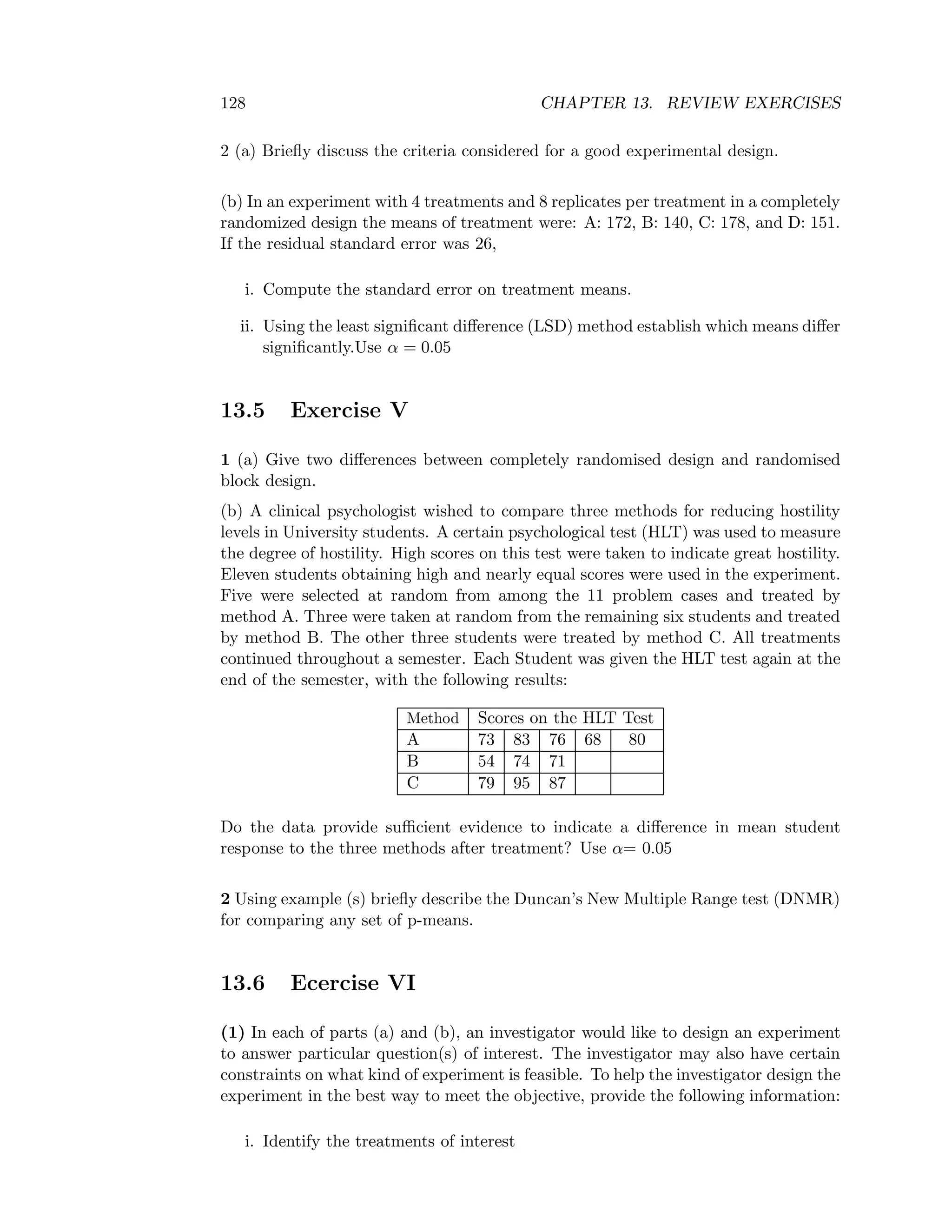

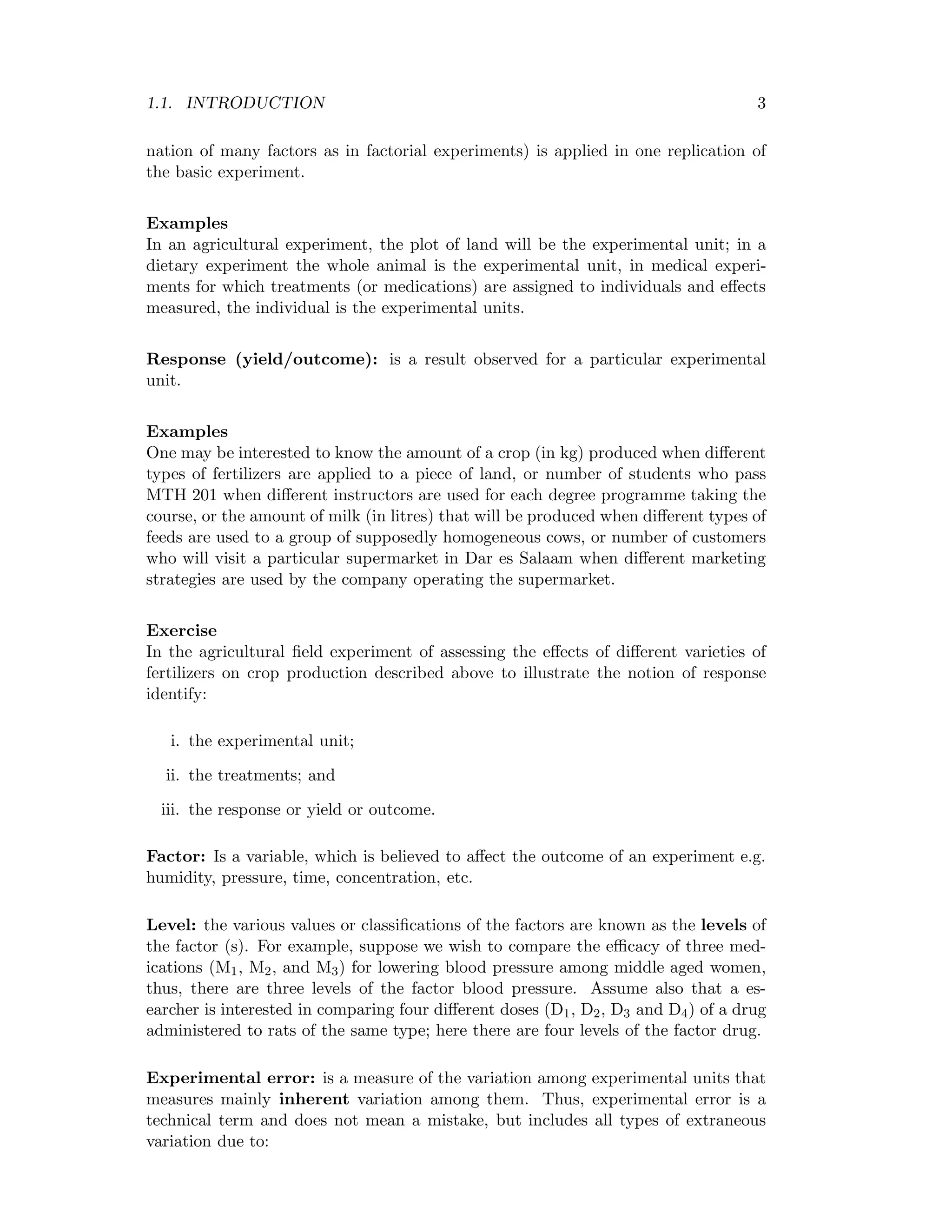

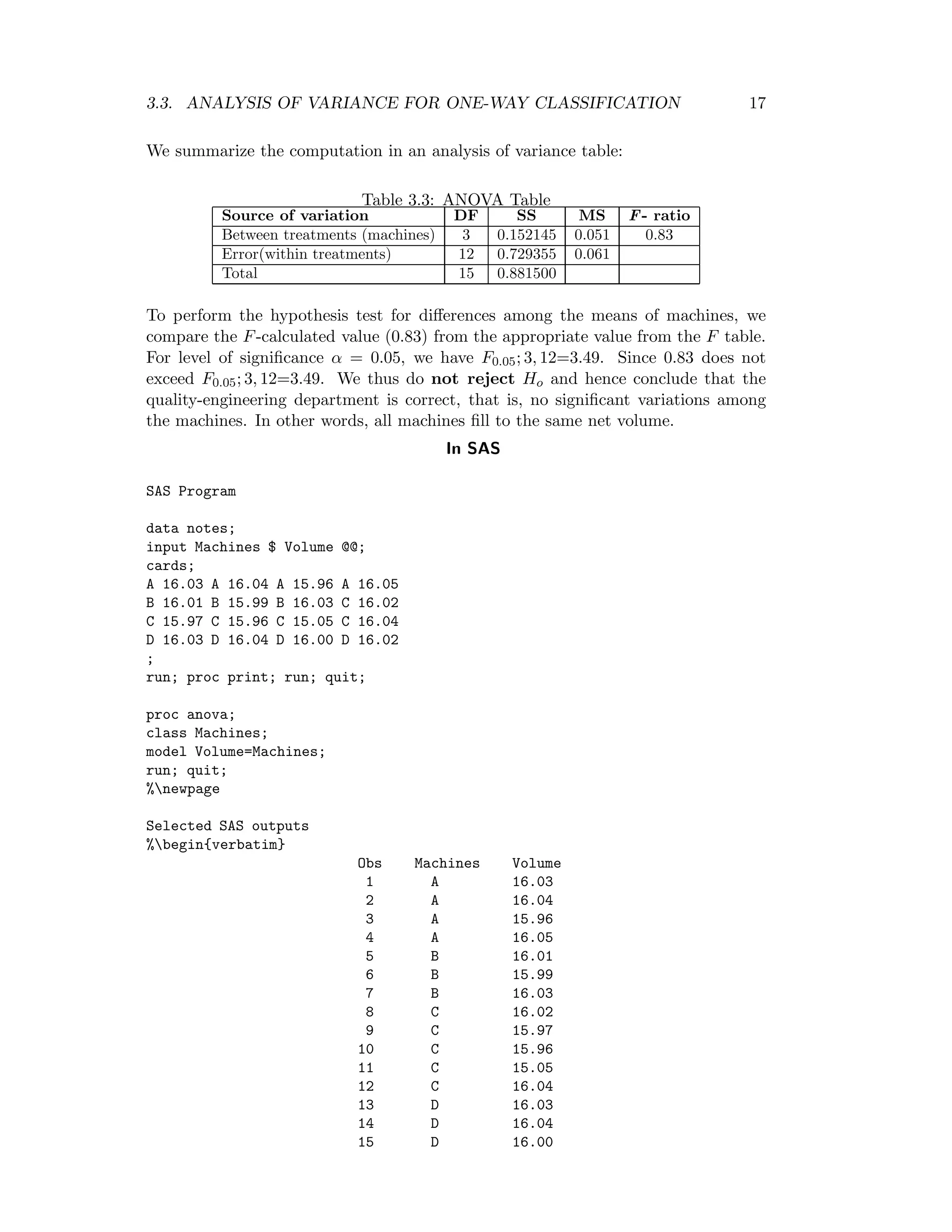

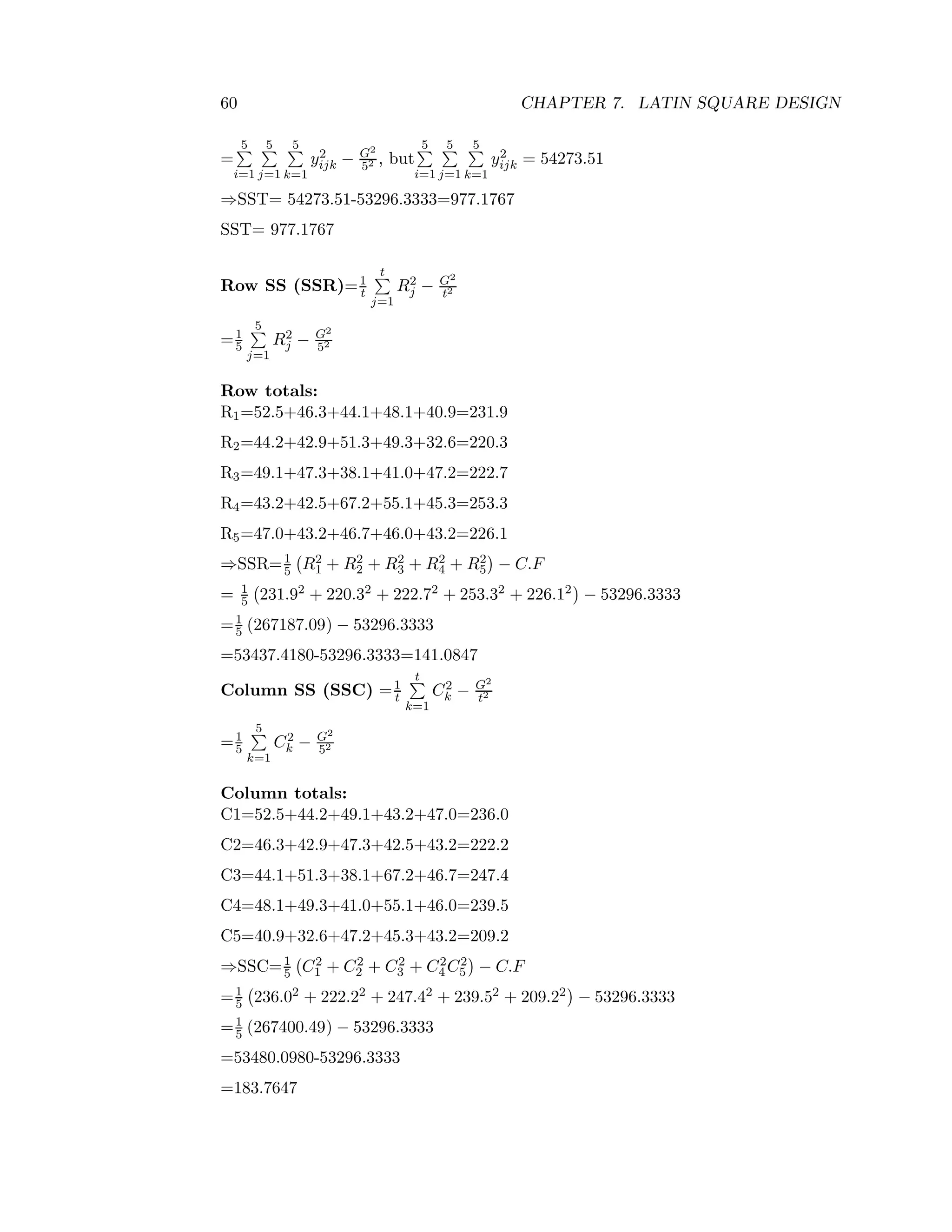

Table 3.6: ANOVA table for two-way classification

Source of variation DF SS MS F-ratio

Factor A h-1 SSA SSA

h−1 = MSA MSA

MSE

Factor B g-1 SSB SSB

g−1 = MSB MSB

MSE

Residual (h-1)(g-1) SSE SSE

(h−1)(g−1) = MSE

Total N-1 SST

Statistical hypotheses:

Factor A:

Ho: t1 = t2=. . . =th

H1: ti =tj for at least one i = j

Factor B:

Ho: b1=b2=. . . =bg

H1: bi =bj for at least one i = j

Test procedure

Reject Ho for factor A, if the calculated F-value MSA

MSE > the tabulated F-value

Fα, [(h − 1) , (h − 1)(g − 1)] at α-level of significance. Otherwise, we do not reject

Ho.

Similarly, reject Ho for factor B, if the calculated F-value MSB

MSE > the tabulated

F-value Fα, [(g − 1) , (h − 1)(g − 1)] at α-level of significance. Otherwise, we do not

reject Ho](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-29-2048.jpg)

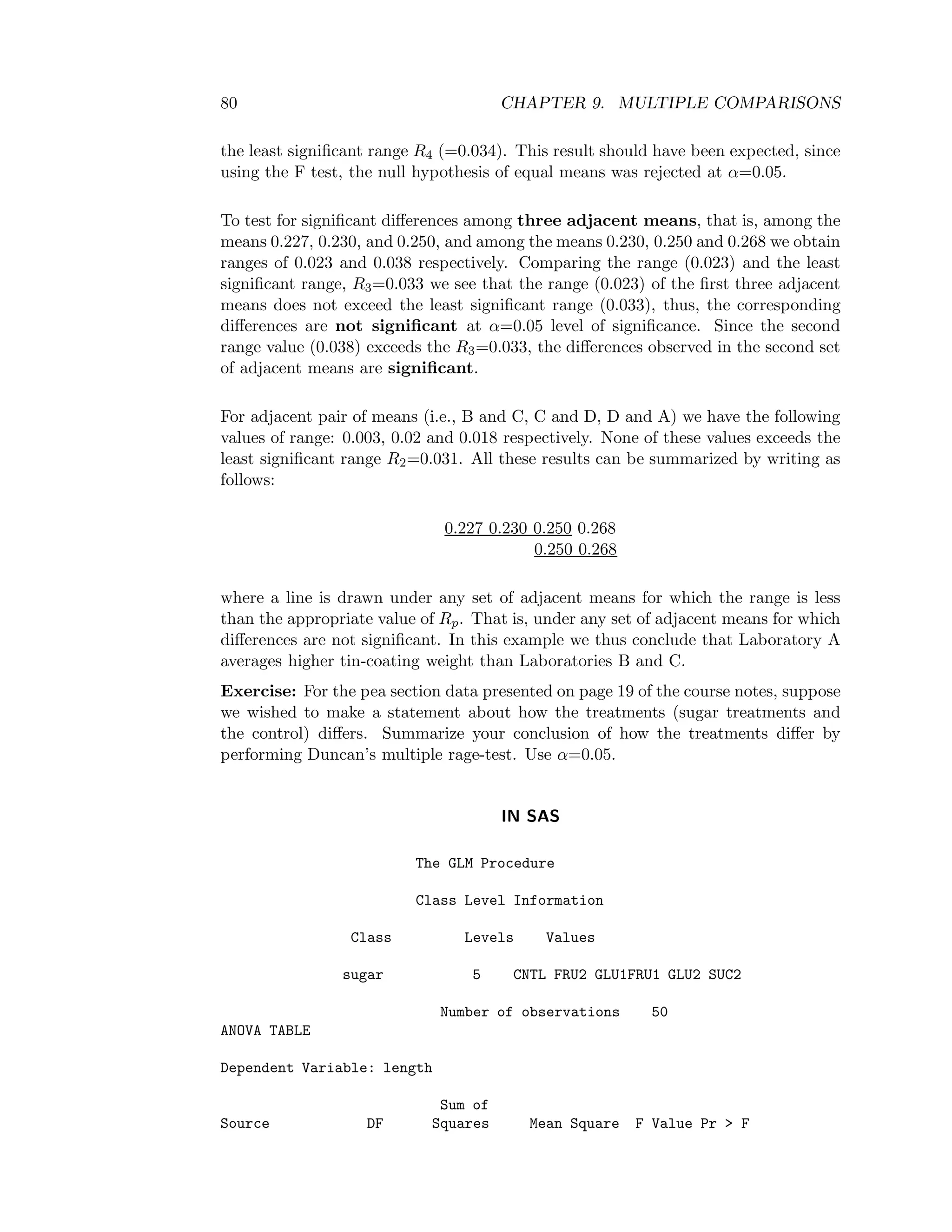

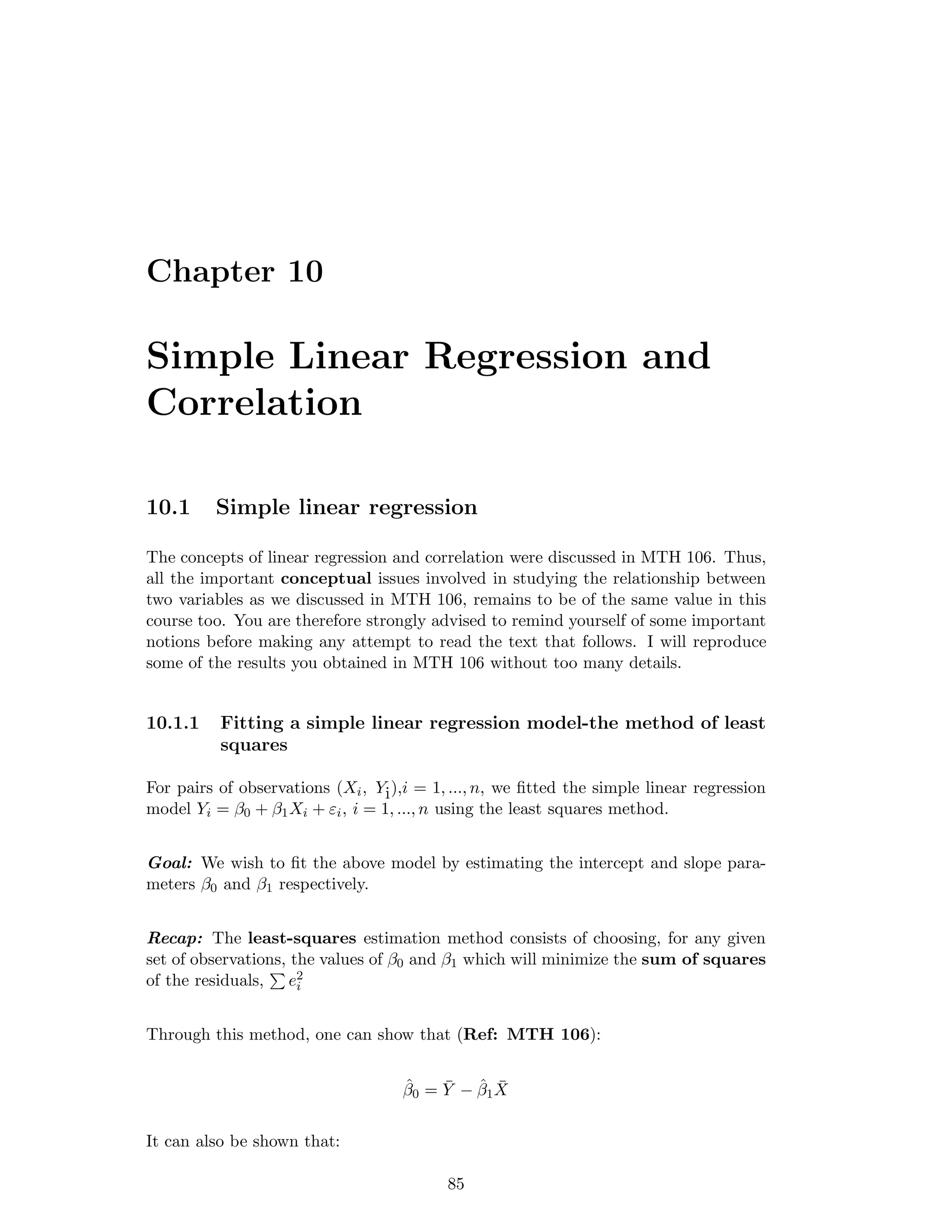

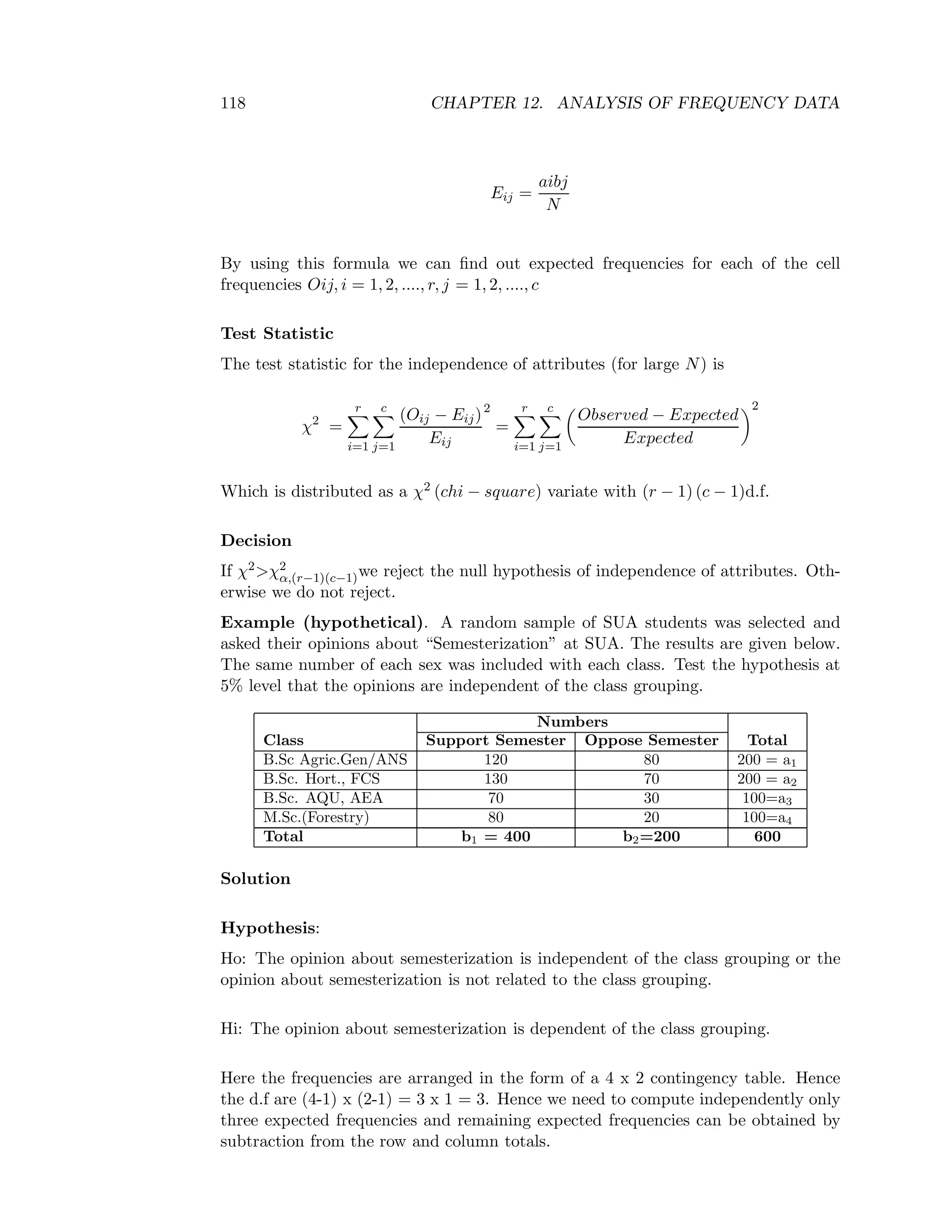

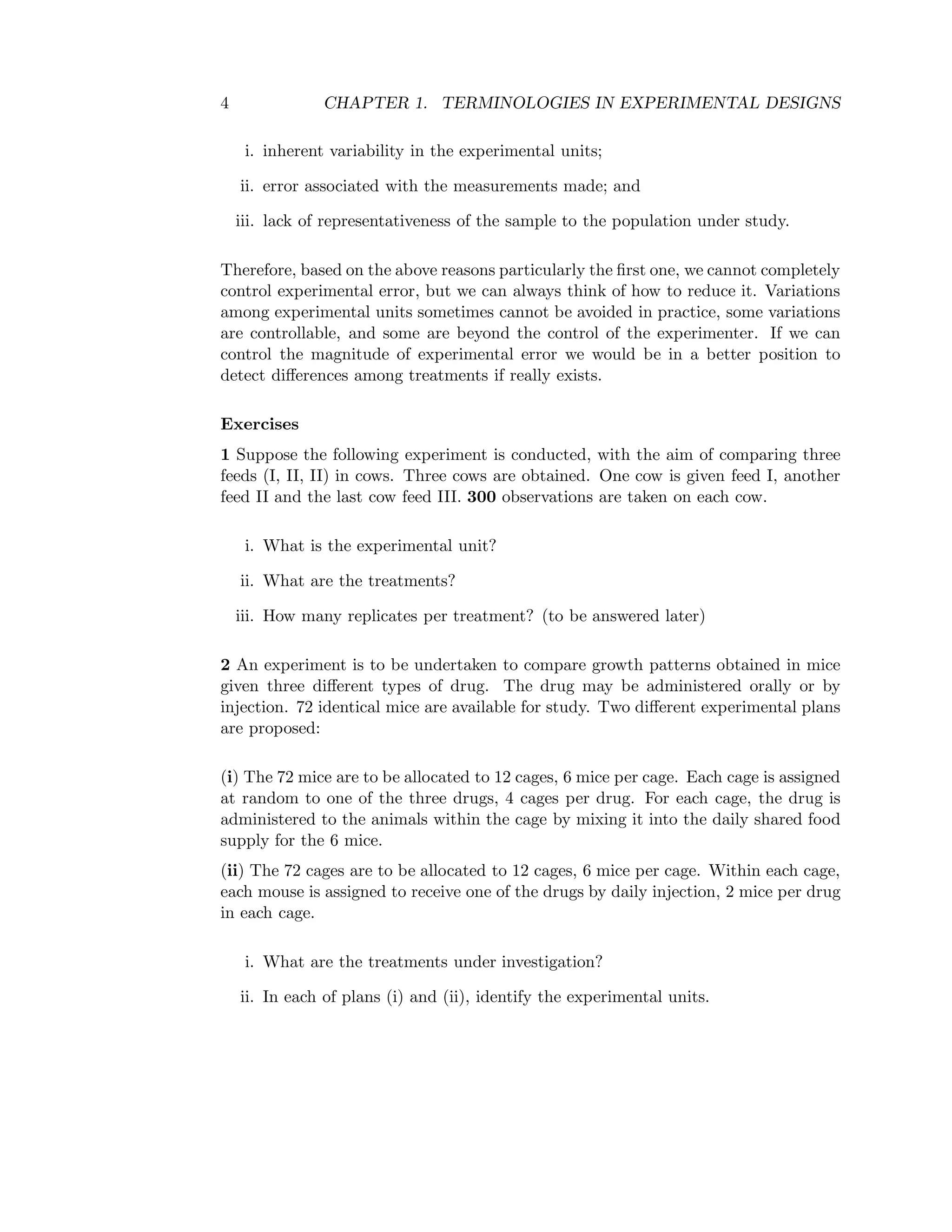

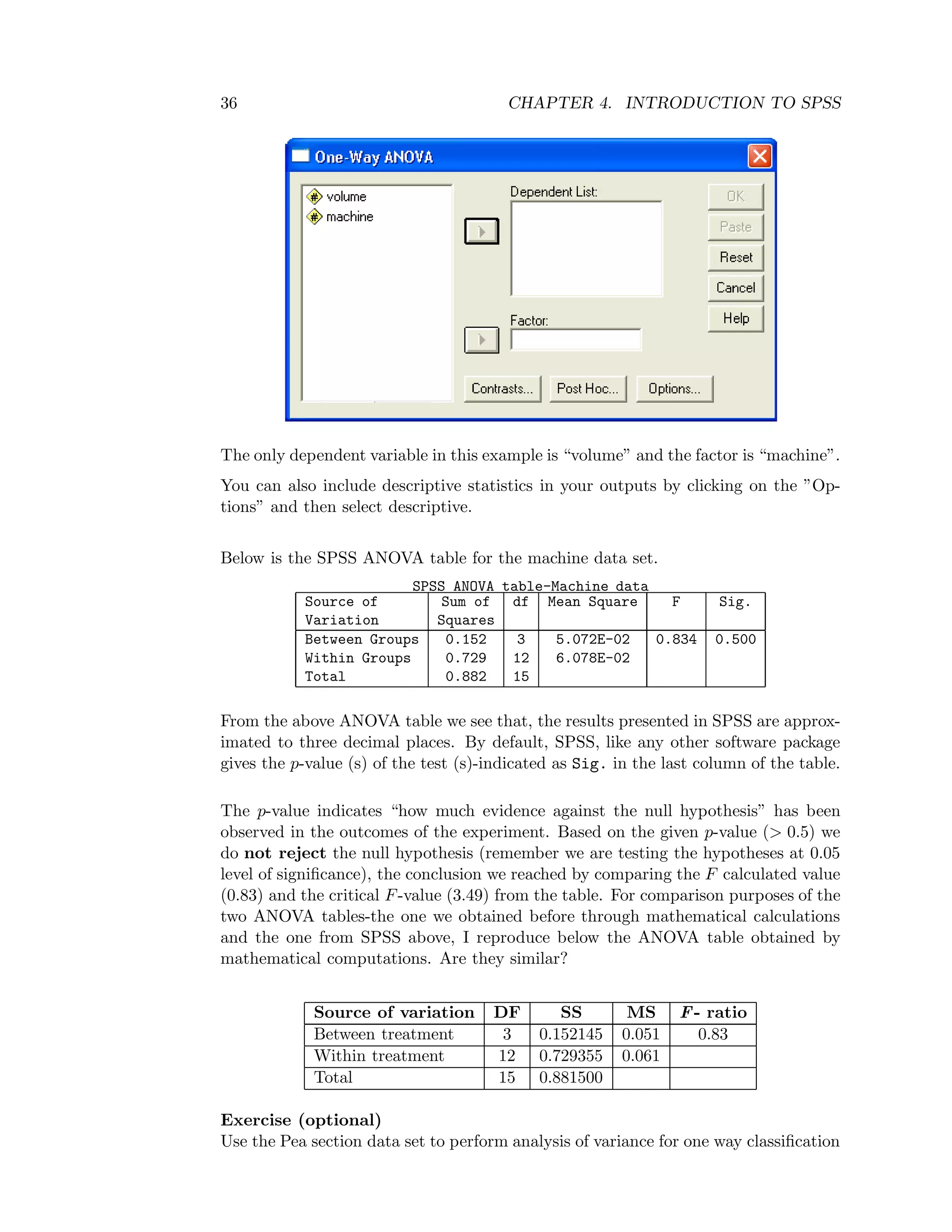

![5.4. ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF CRD 41

Table 5.1: ANOVA table

Source of Variation DF SS MS F-ratio

Treatments t-1 SSA SSA

t−1 = MSA MSA

MSE

Error N − t SSE SSE

N−t = MSE

Total N-1 SST

5.3.2 Test procedure

At level of significanceα, if F = MSA

MSE > Fα, [(t − 1) , (N − t)] then there is evidence

for no significance variation, i.e. we reject the null hypothesis. Otherwise, e do not

reject.

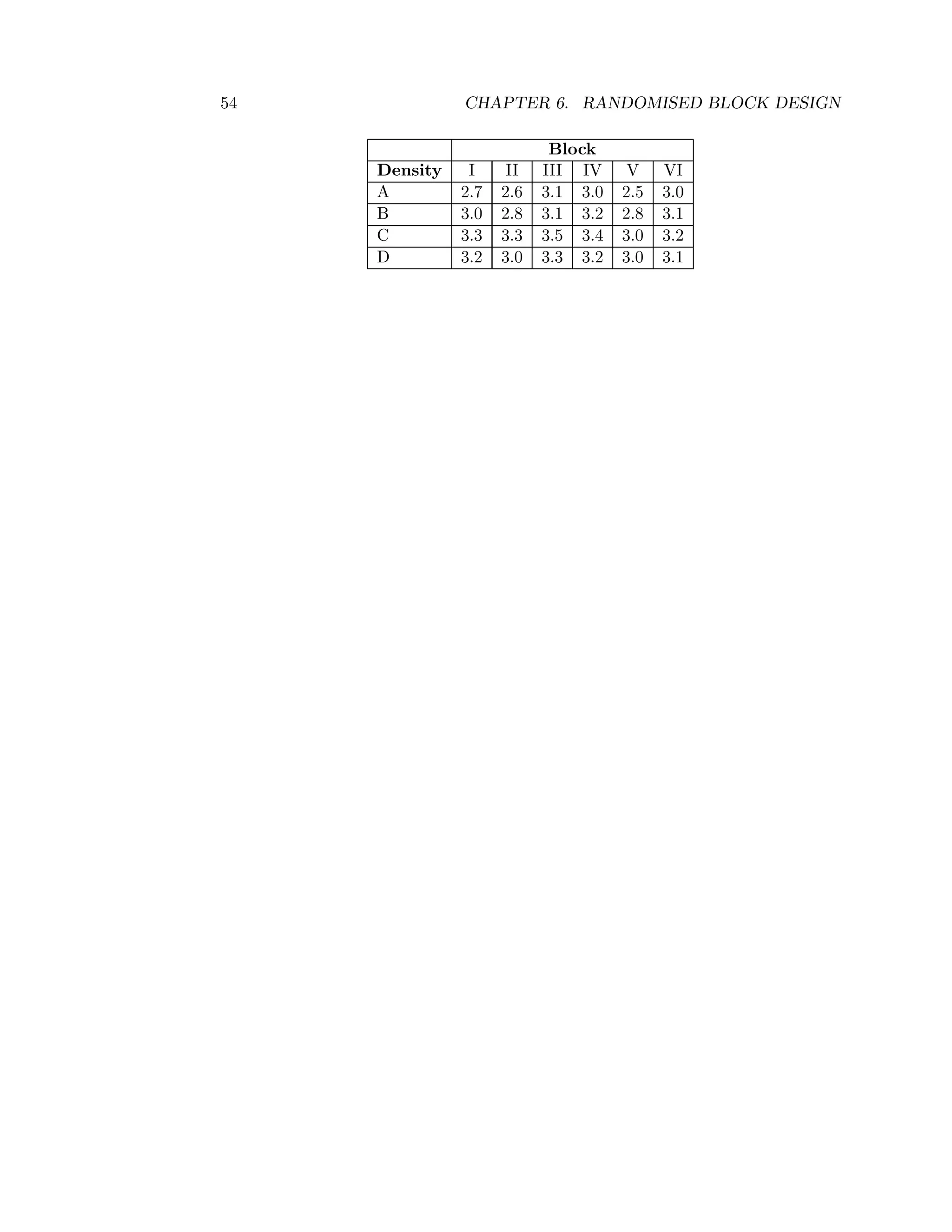

5.4 Advantages and disadvantages of CRD

5.4.1 Advantages

• Useful in small preliminary experiments and also in certain types of animal or

laboratory experiments where the experimental units are homogeneous.

• Flexibility in the number of treatments and the number of their replications.

• Provides maximum number of d.f. for the estimation of experimental error-

The precision of small experiment increases with error d.f.

5.4.2 Disadvantages

• Its use is restricted to those cases in which homogeneous experimental units

are available- local control not utilised. Thus, presence of entire variation may

inflate the experimental error.

• Rarely used in field experiments because the plots are not homogeneous.

5.5 Example

A sample of plant material is thoroughly mixed and 15 aliquots taken from it for

determination of potassium contents. 3 laboratory methods (I, II, and III) are em-

ployed. “I” being the one generally used. 5 aliquots are analysed by each method,

giving the following results (µg/ml).

I 1.83 1.81 1.84 1.83 1.79

Method II 1.85 1.82 1.88 1.86 1.84

III 1.80 1.84 1.80 1.82 1.79

Examine whether methods II and III give results comparable to those of method I.

Use α = 0.05](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-48-2048.jpg)

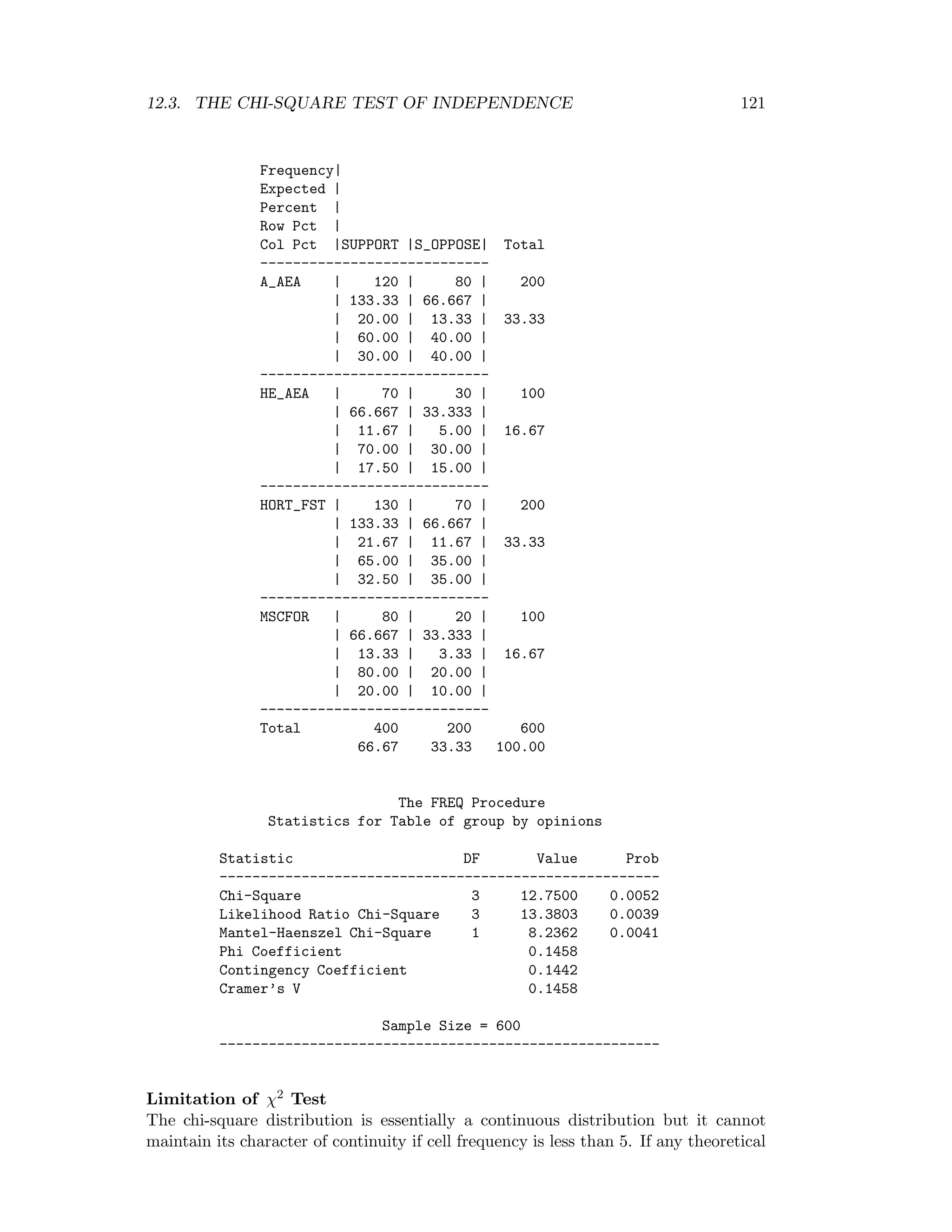

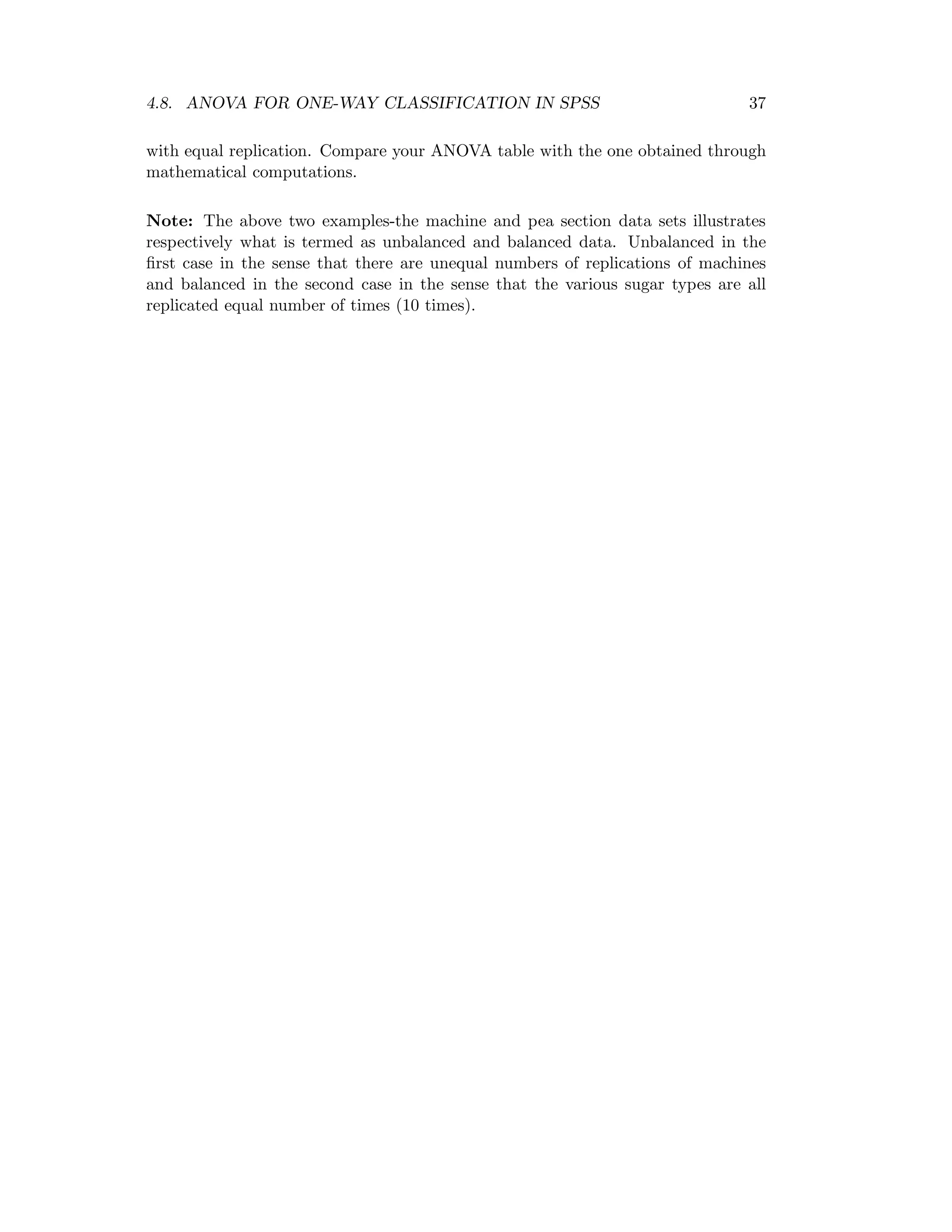

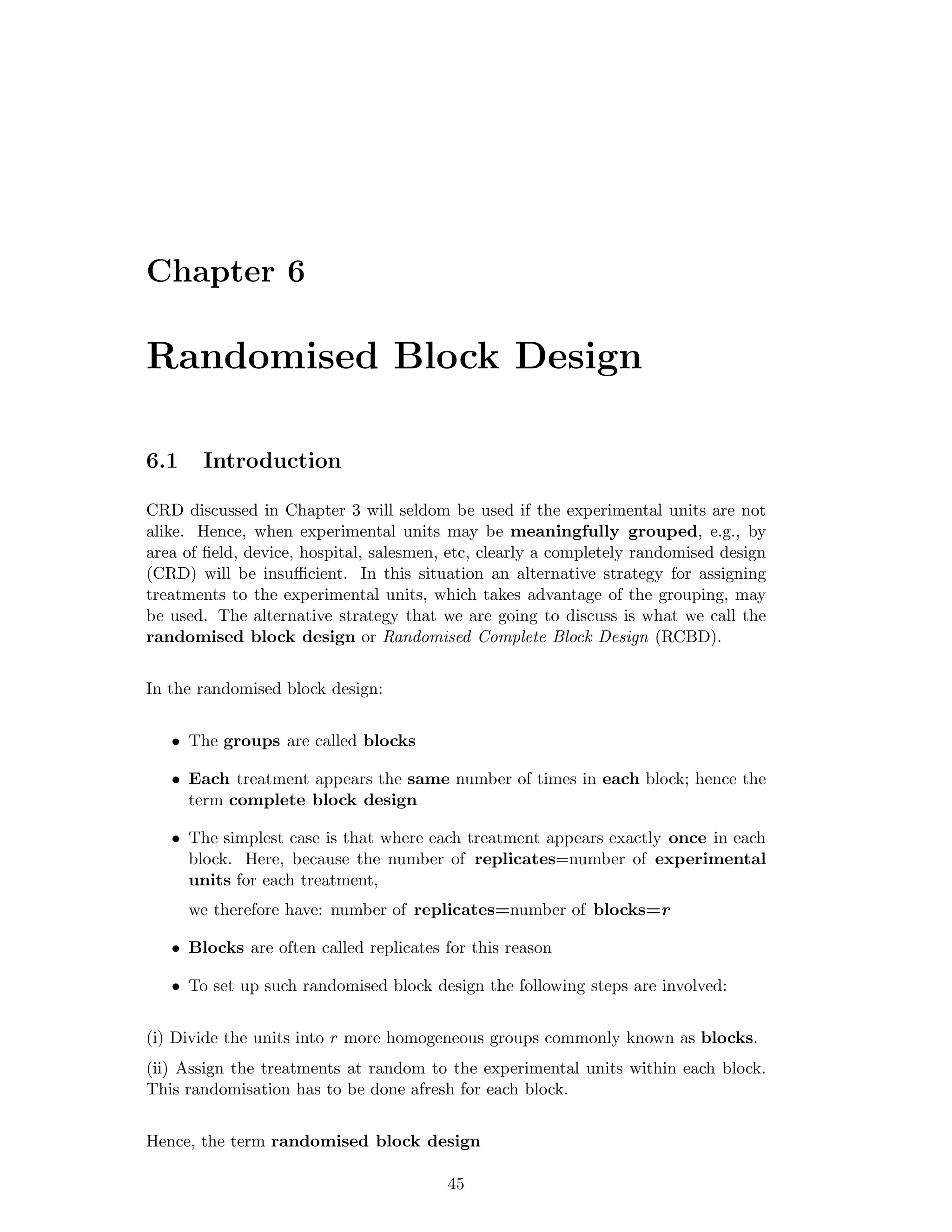

![48 CHAPTER 6. RANDOMISED BLOCK DESIGN

In symbols

Fα, [(t − 1), (r − 1)(t − 1)] and Fα, [(r − 1), (r − 1)(t − 1)]

Thus, if FB>Fα, [(r − 1), (r − 1)(t − 1)] we reject the null hypothesis, otherwise we

do not reject. Also if FTr>Fα, [(t − 1), (r − 1)(t − 1)] we reject the null hypothesis,

otherwise we do not reject.

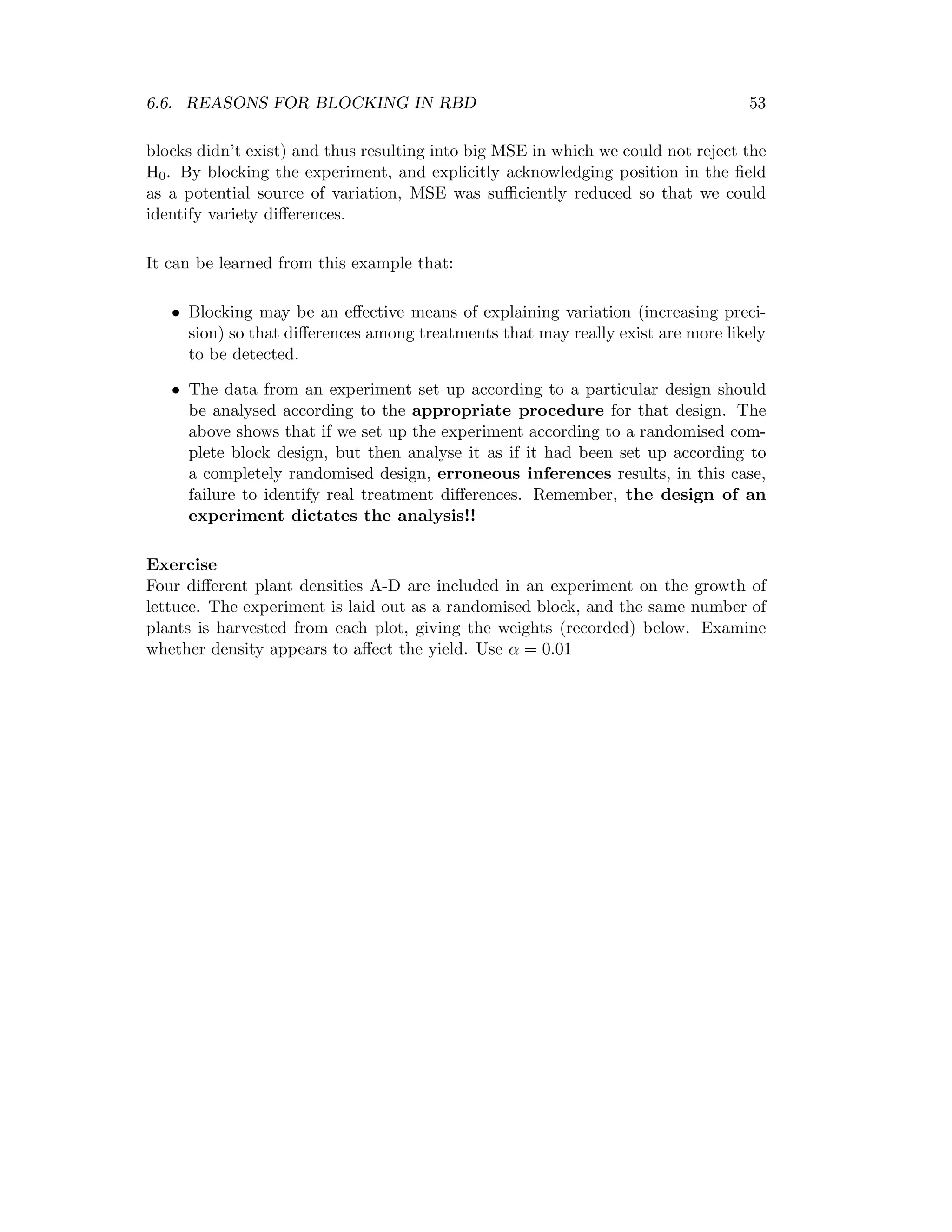

6.4 Advantages and disadvantages of RBD

6.4.1 Advantages

• Greater precision

• Increased scope of inference is possible because more experimental conditions

may be included

6.4.2 Disadvantages

• Large number of treatments increases the block size; as a result the block may

loose homogeneity leading to large experimental error.

• Any missing observation in a unit in a block will lead to either:

(i) discard the whole block

(ii) estimate the missing value from the unit by special missing plot technique.

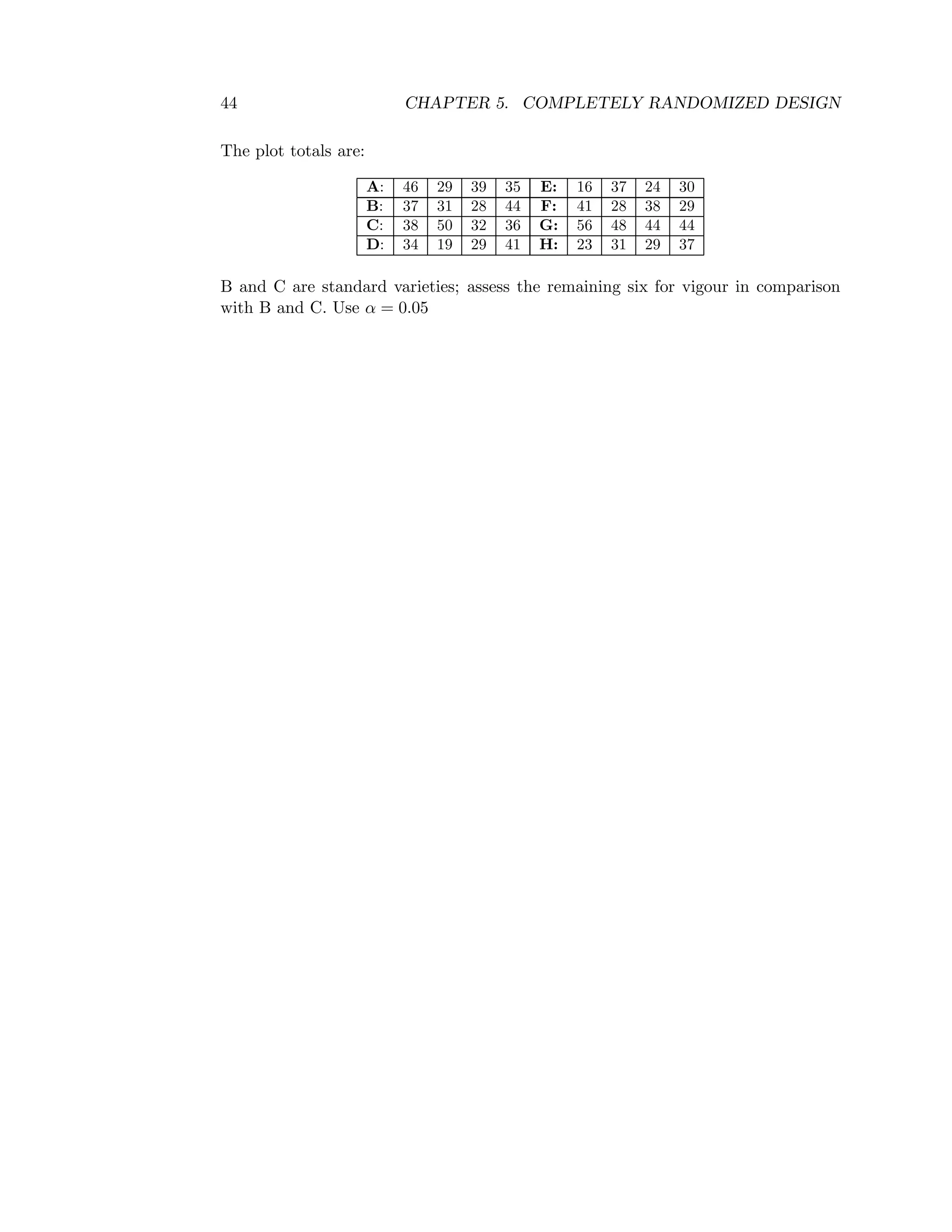

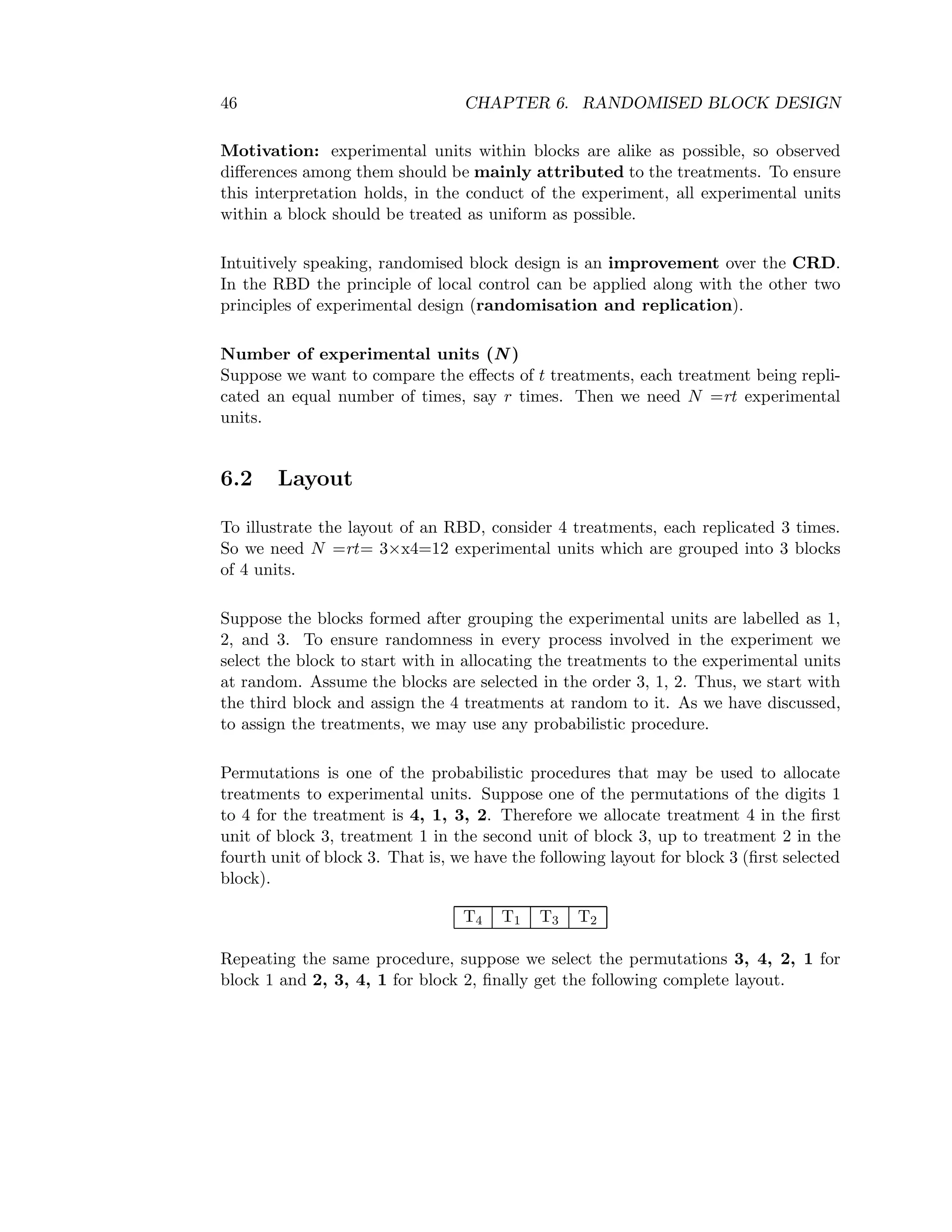

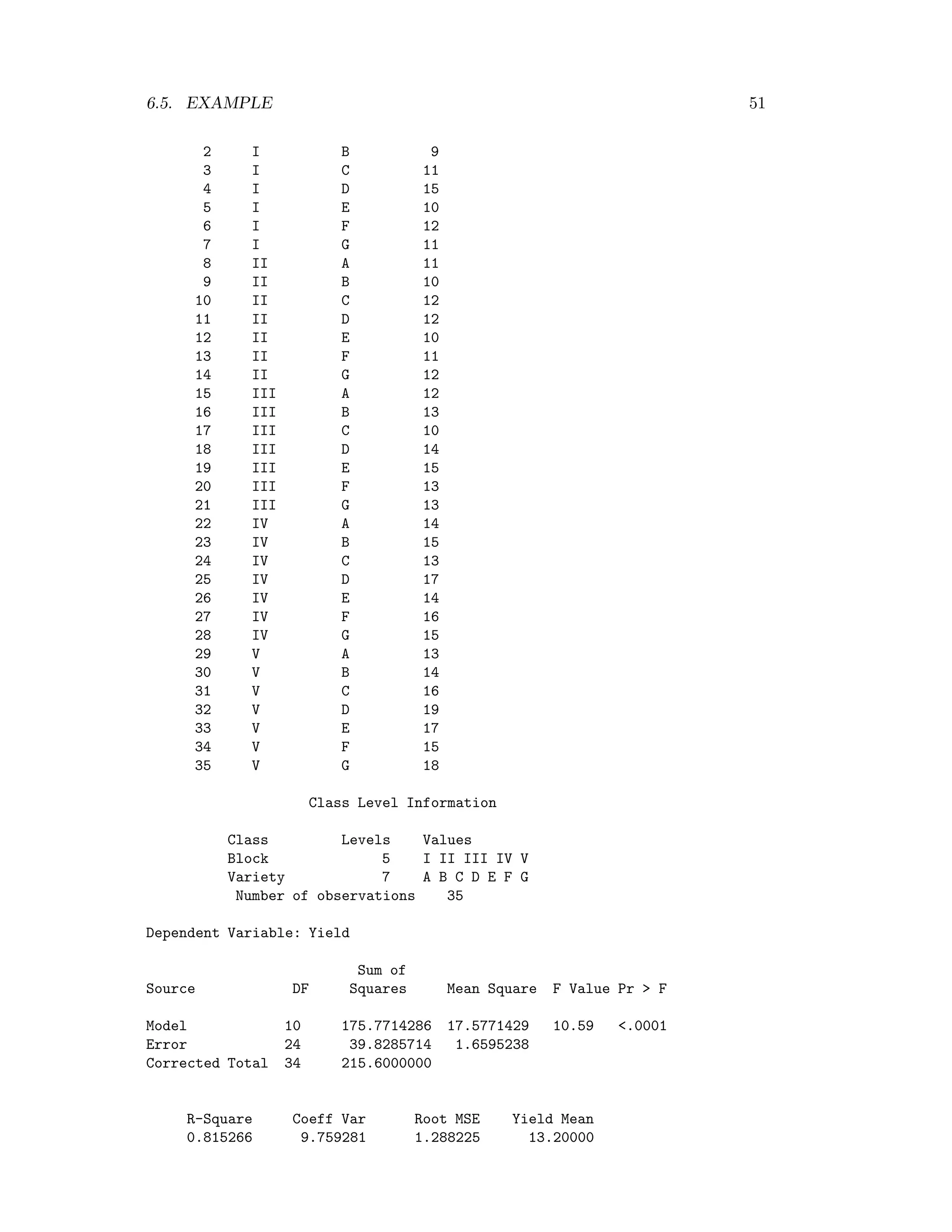

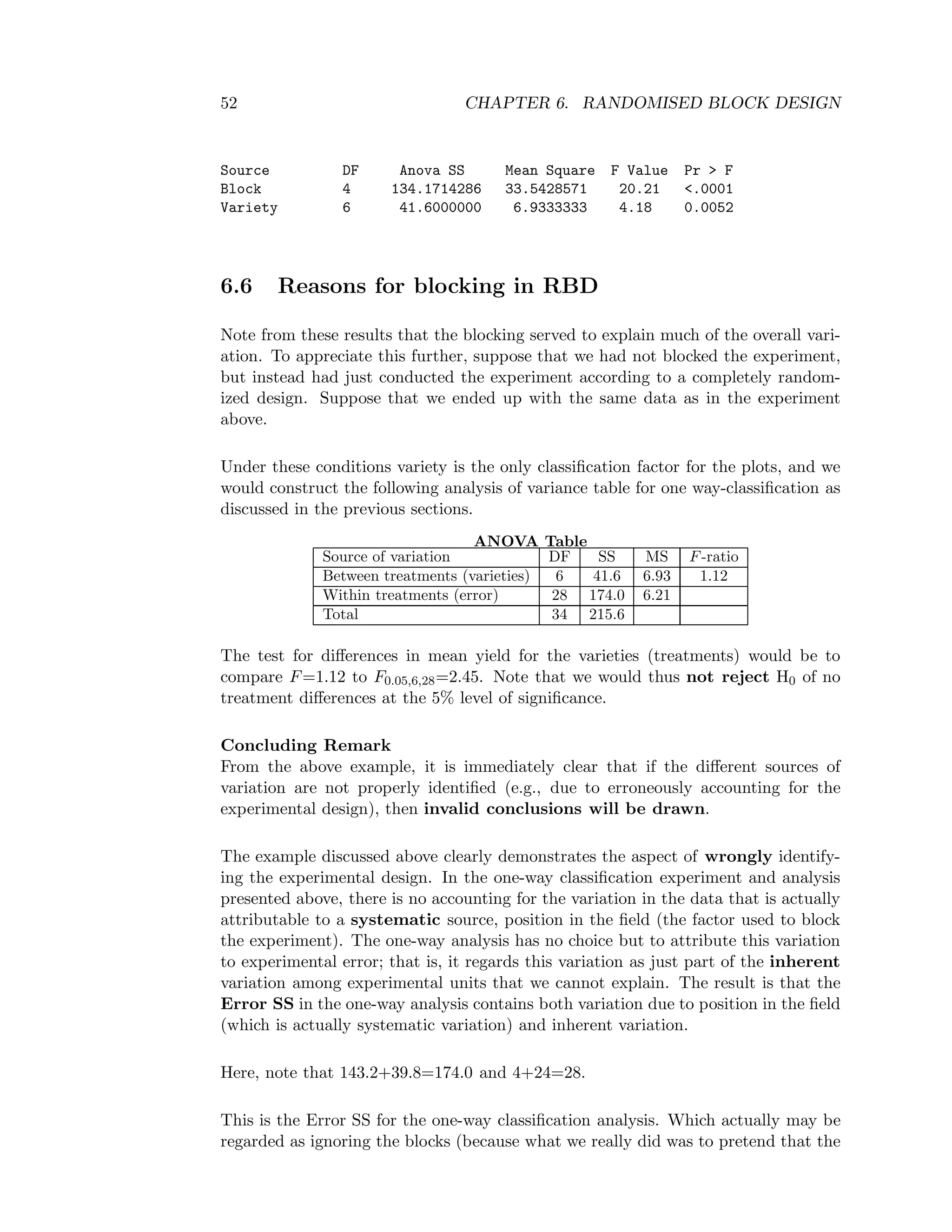

6.5 Example

The following data are yields in bushels/acre from an agricultural experiment set out

in a randomised complete clock design. The experiment was designed to investigate

the differences in yield for seven hybrid varieties of wheat, labelled A-G here. A field

was divided into 5 blocks, each containing 7 plots. In each plot, the seven plots were

assigned at random to be planted with the seven varieties, one plot for each variety.

A yield was recorded for each plot. Examine whether varieties affect the yield. Use

α=0.05.

Variety

Block A B C D E F G Total

I 10 9 11 15 10 12 11 78

II 11 10 12 12 10 11 12 78

III 12 13 10 14 15 13 13 90

IV 14 15 13 17 14 16 15 104

V 13 14 16 19 17 15 18 112

Total 60 61 62 77 66 67 69 G=462](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-55-2048.jpg)

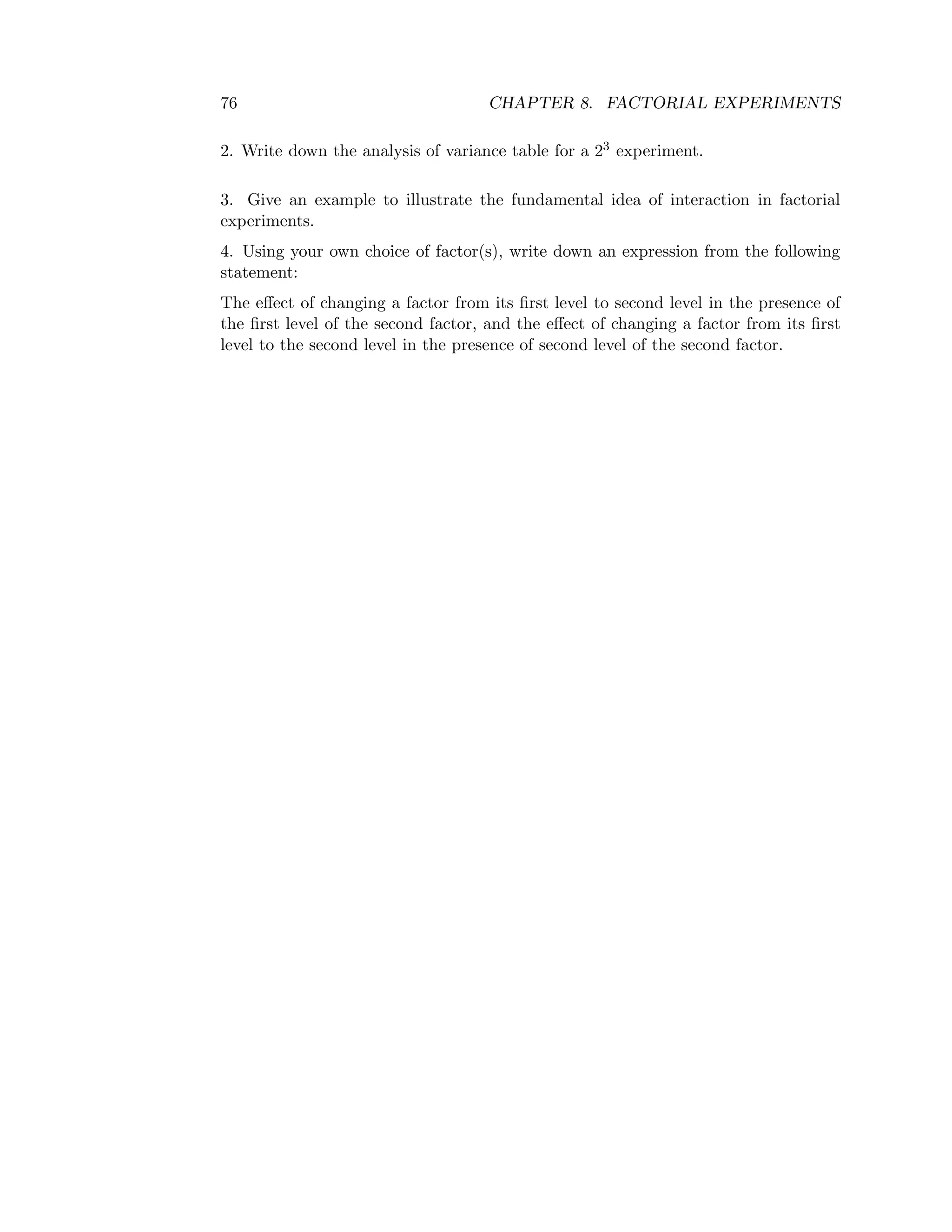

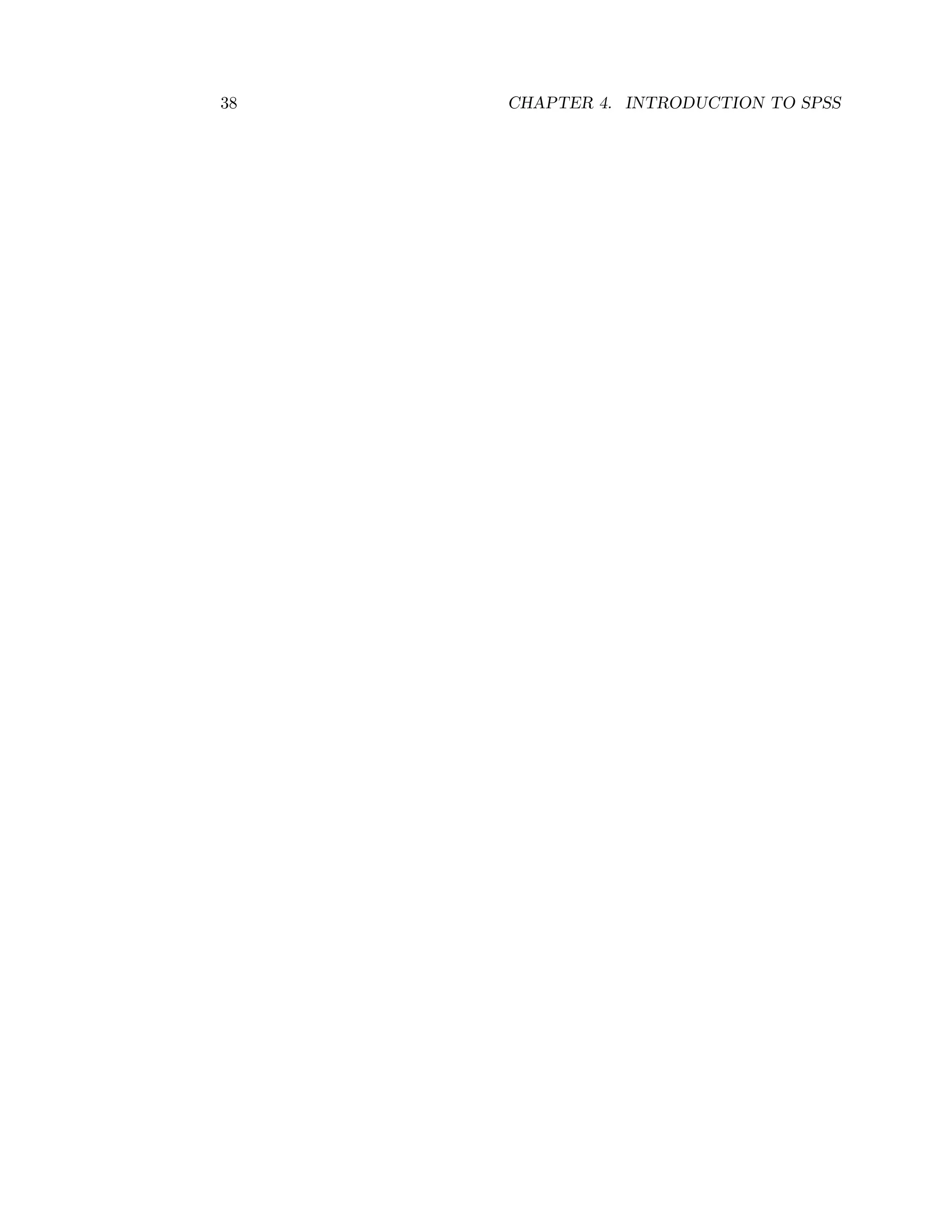

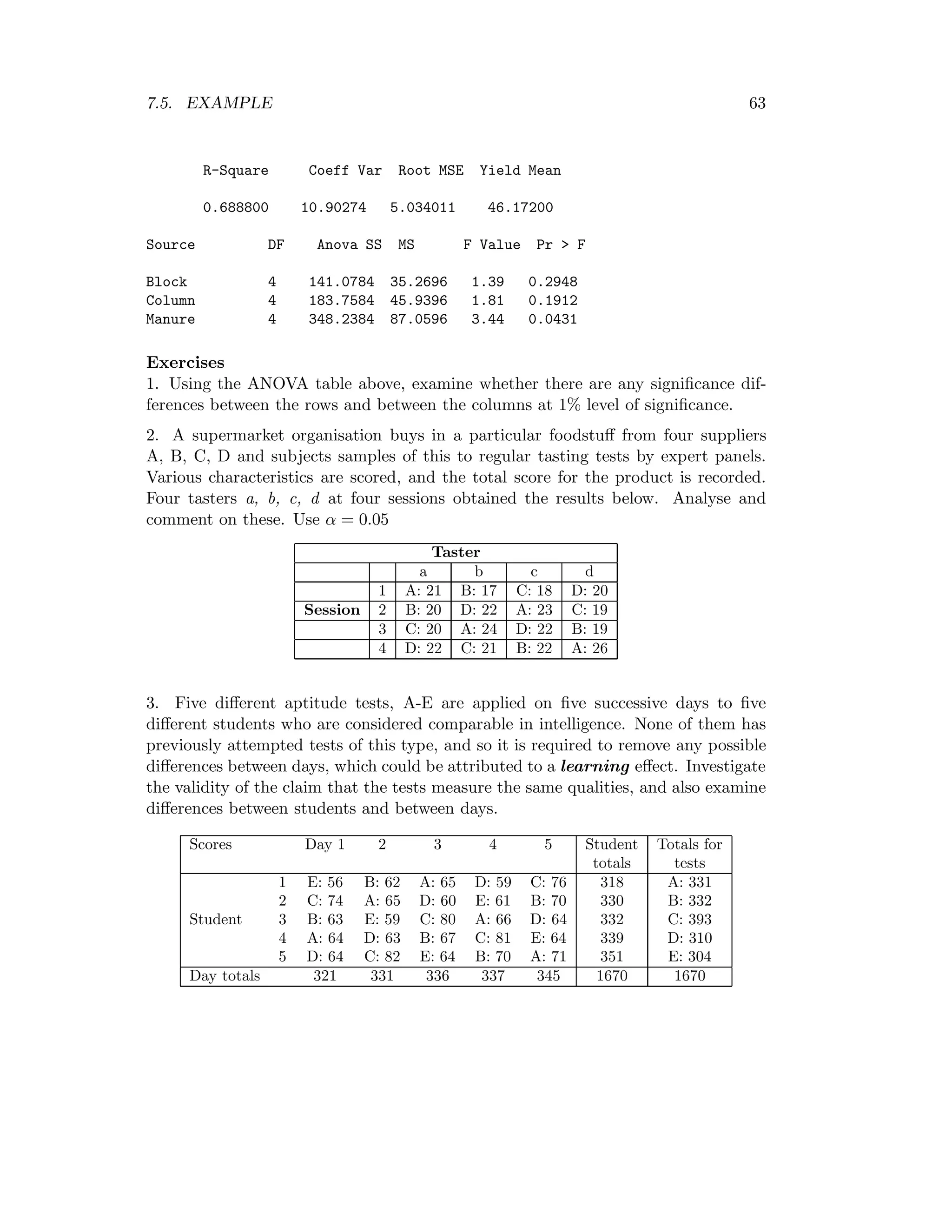

![66 CHAPTER 8. FACTORIAL EXPERIMENTS

8.2 Main effects and interaction effects

The effects in a factorial experiment are composed of main effects and interaction

effects.

A main effect of a factor is defined as a measure of the average change in effect

produced by changing the levels of the factor. It is measured independently of other

factors.

Factors are said to interact when they are not independent. But “interaction”

in a factorial experiment is a measure of the extent to which the effect of changing

the levels of one or more factors depends on the levels of the other factors.

Interactions between two factors are referred to as first order interaction, those

concerning three factors are referred to as second order interaction and so on.

8.3 The 22

factorial experiments

Let the symbols aibj (i=o, l, j=o,l) represent both the treatment combination and

yields from all experimental units or plots.

Effect of factor a at level b0 of factor b = a1b0 – a0b0.

Effect of factor a at level b1 of factor b = a1b1 – a0b1.

Therefore, the main effect of factor a = average change produced by varying the

levels of factor a.

= 1

2 [(a1bo − aobo) + (a1b1 − aob1)]

= 1

2 [b0 (a1 − ao) + b1 (a1 − ao)]

= 1

2 [(a1 − ao) (bo + b1)]

Therefore, the main effect of factor a = 1

2 (a1 − ao) (bo + b1) = A

Similarly the main effect of factor b.

Effect of factor b at level a0 of factor a

= a0b1-a0b0

Effect of factor b at level a1, of factor a

= a1b1-a1b0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-73-2048.jpg)

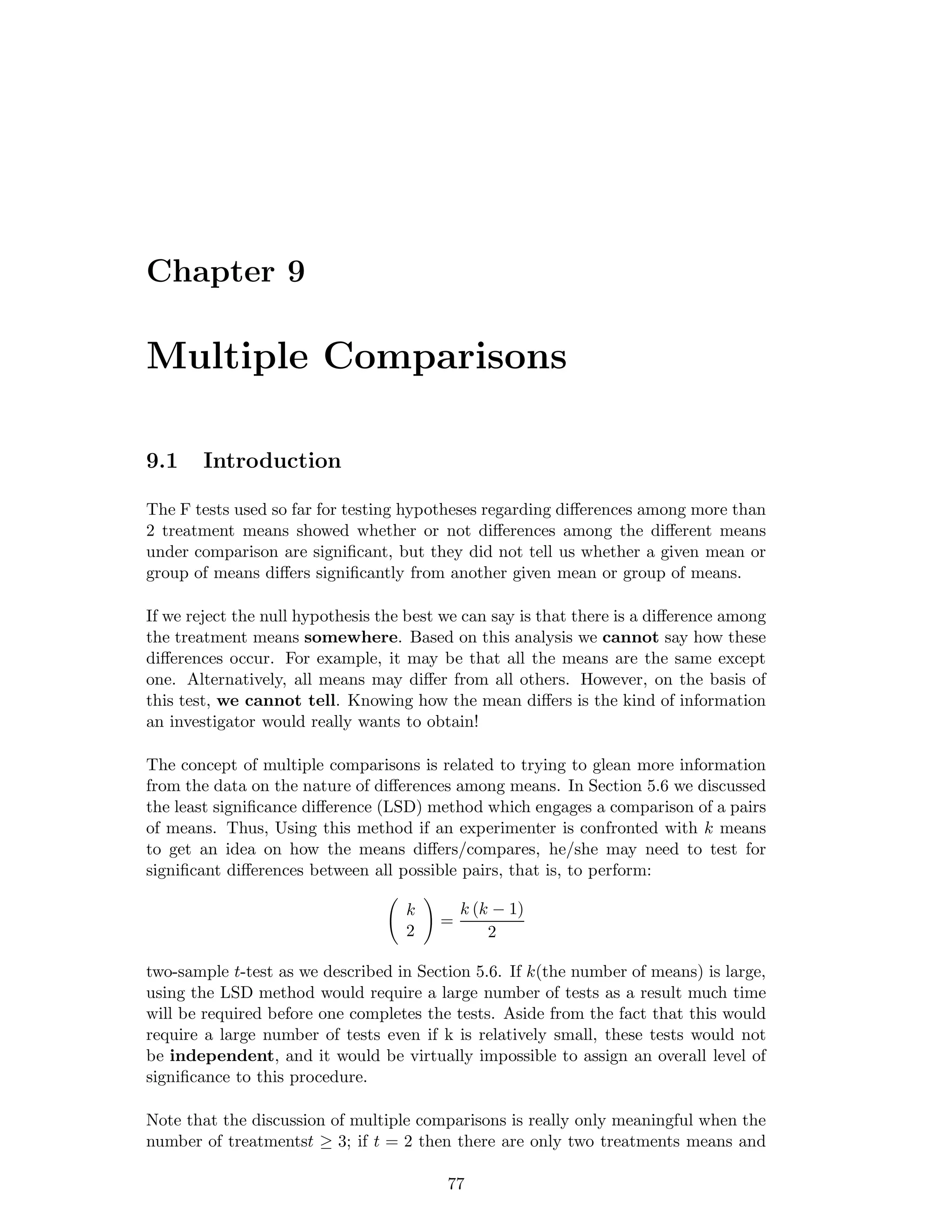

![8.3. THE 22 FACTORIAL EXPERIMENTS 67

Therefore, the main effect of factor b

= 1

2 [(aob1 − aobo) + (a1b1 − a1bo)]

= 1

2 [(b1 − b0) a0 + (b1 − b0) a1]

= 1

2 [(b1 − b0) (a0 + a1)]

= 1

2 (b1 − b0) (a1 + a0) = B

If the two factors “a” and “b” were acting independently the effect of factor a at

level b0 and the effect of factor a at level b1 or the effect of factor b at level a0 and

the effect of factor b at level a1 should be equal, but in general they will be different.

This difference is a measure of the extent to which the factors interact. Hence A×B,

the interaction between two factors “a” and “b” each at 2 levels, zero and one is

given by

A × B =

1

2

[(a1b1 − a0b1) − (a1b0 − a0b0)]

A × B =

1

2

(a1 − a0) (b1 − b0)

It is clear from this relation that interaction between factors “a” and “b” i.e. A×B

is the same as that between “b” and “a” i.e. B×A.

The overall mean is represented by M

i.e. M = 1

4 [a0b0 + a0b1 + a1b0 + a1b1]

= 1

4 [a0(b0 + b1) + a1(b0 + b1)]

=1

4 [(a0 + a1)(b0 + b1)]

= 1

4 (a1 + a0) (b1 + b0)

Replacing the symbols a0 and b0 by 1 and the symbols a1 and b1 by simple aand b

respectively, the preceding comparisons may be expressed by

A = 1

2 (a − 1) (b + 1)

B = 1

2 (a + 1) (b − 1)

AB = 1

2 (a − 1) (b − 1)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-74-2048.jpg)

![68 CHAPTER 8. FACTORIAL EXPERIMENTS

M = 1

4 (a + 1) (b + 1)

Expanding say A, A = 1

2 [ab + a − b − 1]

= 1

2 [ab − b + a − 1]

Then, these effects can be conveniently written in a table of plus and minus signs as

shown below:

Effect Treatment Combination Divisor

(1) a b ab

M + + + + 4

A - + - + 2

B - - + + 2

AB + - - + 2

Note: It should be noted that the effects A, B, and AB are three mutually orthogonal

contrasts of the yields of the 4 treatments each based on 1 d.f. i.e. The sum of

products of the corresponding coefficients of the contrasts say A and AB is equal to

zero.

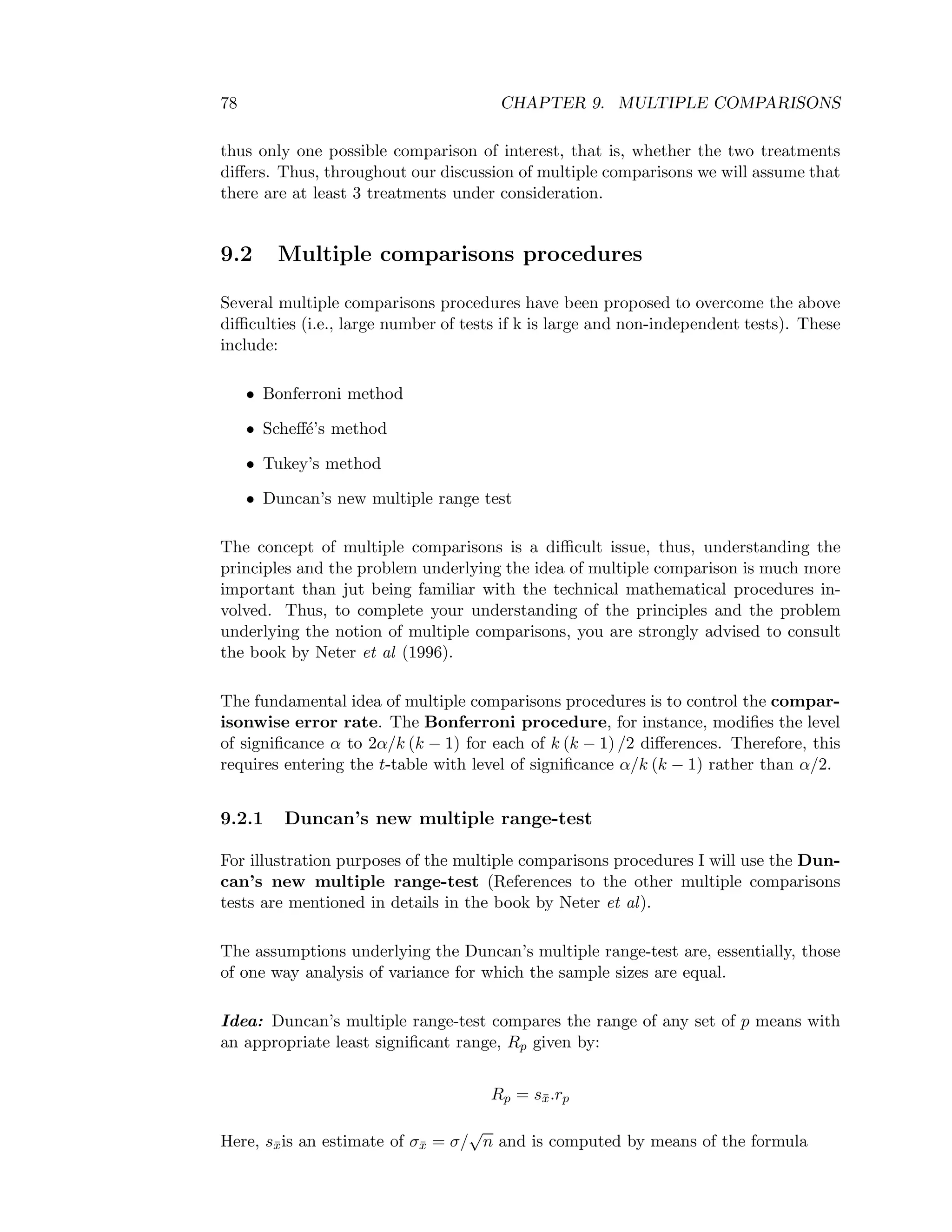

8.4 The 23

factorial experiments

In this case we consider 3 factors a, b, and c each at 2 levels. Hence we get 8 different

treatment combinations, which are listed below.

a0b0c0, a1b0c0, a0b1c0, a0b0c1, a1b1c0, a1b0c1,a0b1c1, a1b1c1 or

(1), a, b, c, ab, ac, bc, abc

The main effects and interactions as defined before can be represented by the fol-

lowing relations:

A = 1

4 (a − 1) (b + 1) (c + 1)

B = 1

4 (a + 1) (b − 1) (c + 1)

C = 1

4 (a + 1) (b + 1) (c − 1)

AB = 1

4 (a − 1) (b − 1) (c + 1)

AC =1

4 (a − 1) (b + 1) (c − 1)

BC = 1

4 (a + 1) (b − 1) (c − 1)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-75-2048.jpg)

![8.5. SUM OF SQUARES DUE TO FACTORIAL EFFECTS 69

ABC = 1

4 (a − 1) (b − 1) (c − 1)

The overall mean in this case is written as

M = 1

8 (a + 1) (b + 1) (c + 1)

The divisor (8) is due to the fact hat we have 8 different treatment combinations (as

listed above) to average out.

Expanding A we have,

A = 1

4 [− (1) + (a) − (b) + (ab) − (c) + (ac) − (bc) + (abc)]

Similarly, expanding B we have

B = 1

4 [− (1) − (a) + (b) + (ab) − (c) − (ac) + (bc) + (abc)]

The expression above can also be summarized by the following plus and minus signs

table.

Effect Treatment Combination Divisor

(1) a b ab c ac bc abc

M + + + + + + + + 8

A - + - + - + - + 4

B - - + + - - + + 4

C - - - - + + + + 4

AB + - - + + - - + 4

AC + - + - - + - + 4

BC + + - - - - + + 4

ABC - + + - + - - + 4

The above table can be extended to include up to n factors all at two levels by

corresponding the expression:

1

2n−1 (a ± 1) (b ± 1) (c ± 1)

Where a minus sign appears in any factor on right if the corresponding letter is

on the left or give to each of the treatment combination a plus sign where the

corresponding factor is at the second level and a minus sign where it is at the first

level.

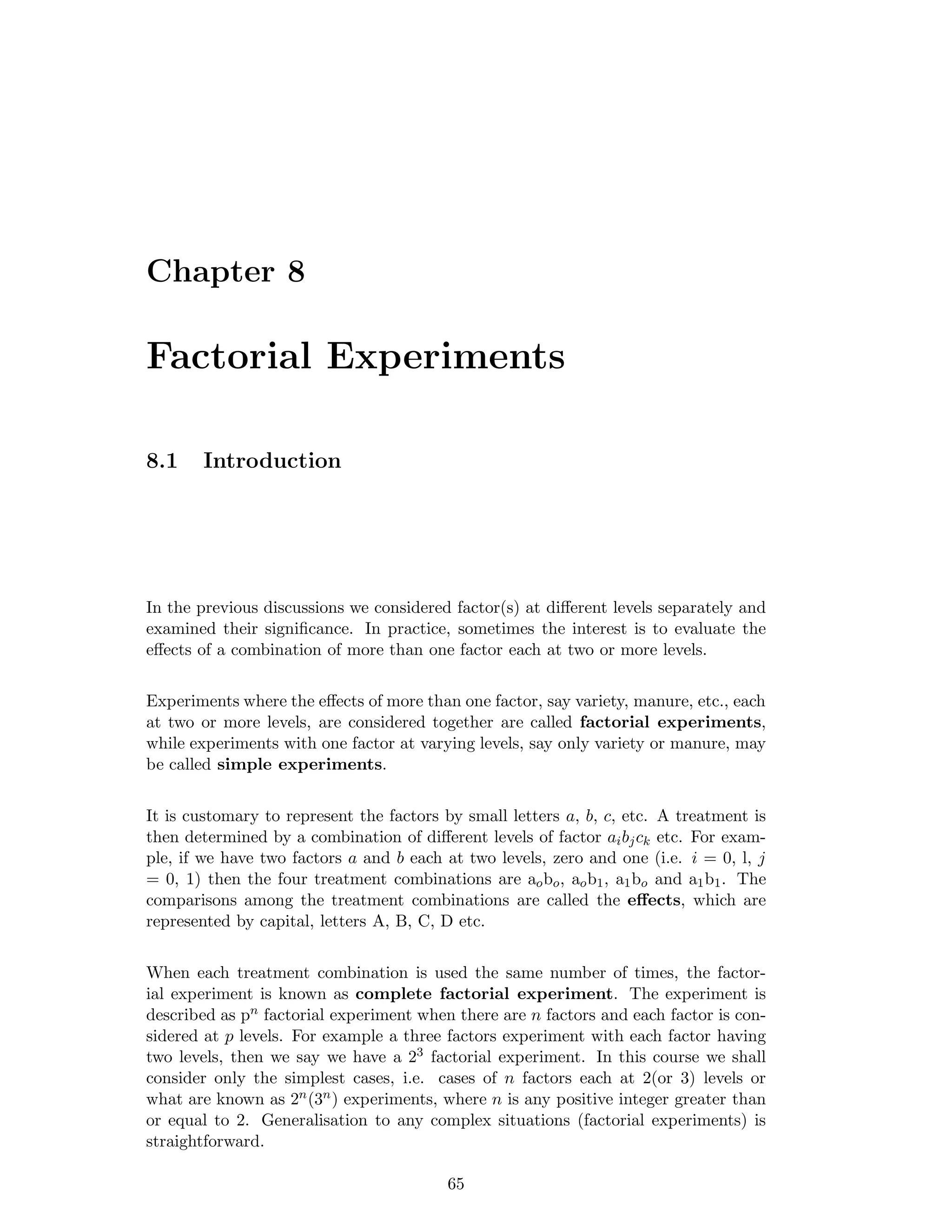

8.5 Sum of squares due to factorial effects

To conduct the tests of significance using the analysis of variance technique, we need

to estimate the sum of squares. In factorial experiments the basic sum of squares](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-76-2048.jpg)

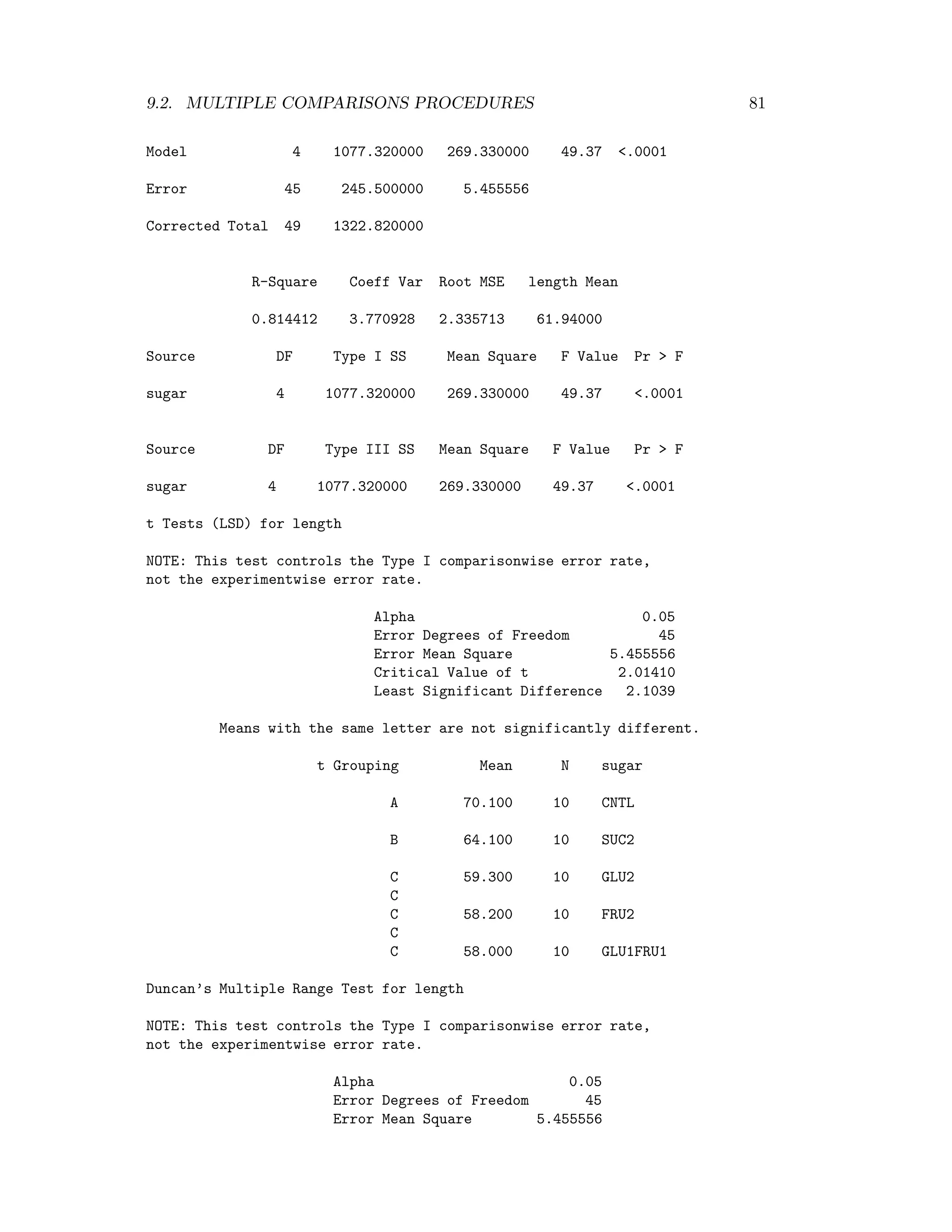

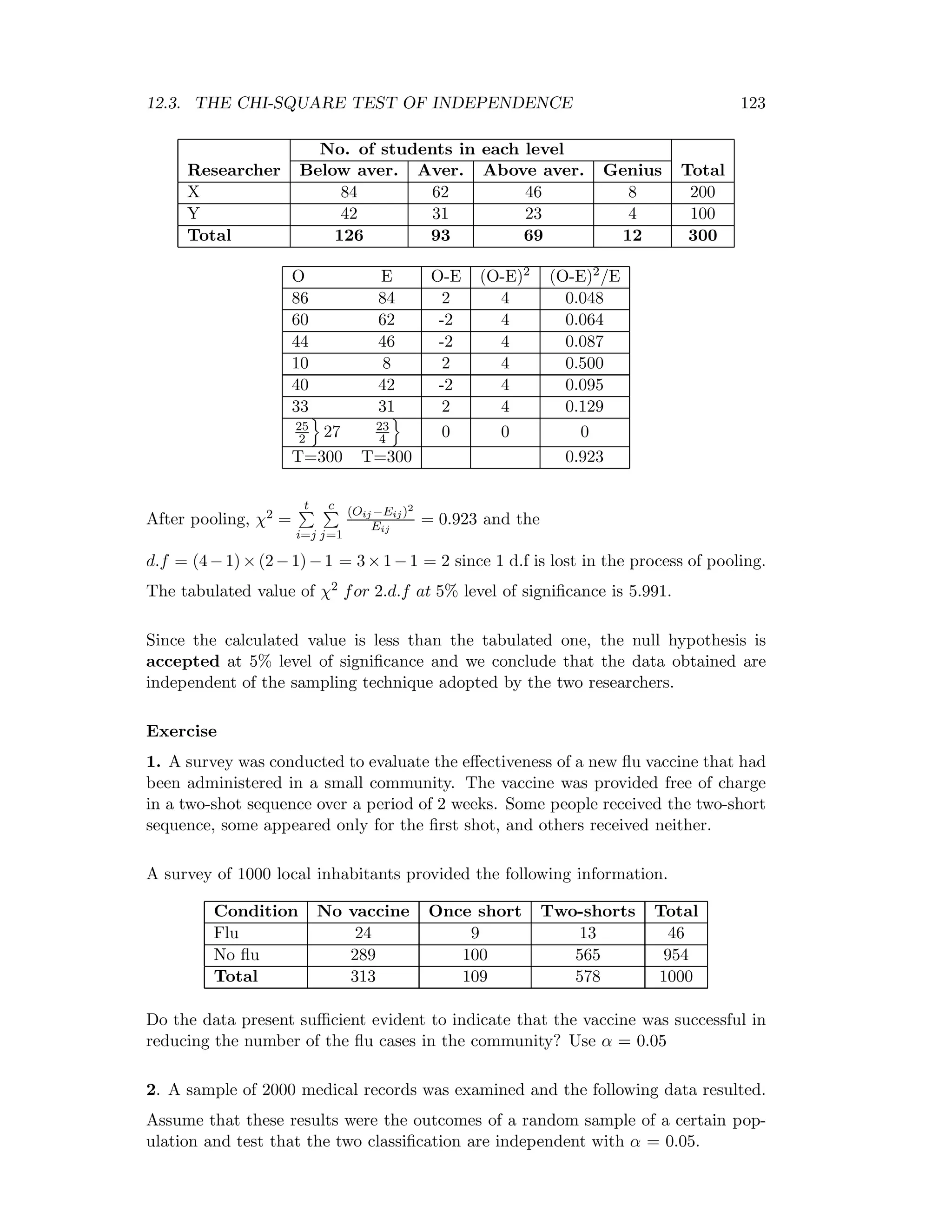

![70 CHAPTER 8. FACTORIAL EXPERIMENTS

are computed in the usual way with the addition that the treatment sum of squares

is further partitioned into component parts of main effects and interaction.

The design structure may be CRD, RBD or LSD but it is the treatments that have

a factorial structure.

To compute the sum of squares let us consider a 22 factorial experiment, which has

been carried out in an RBD with r replications or blocks. The statistical model as

we discussed before would be:

yij = µ + ti + bj + eij

The block SS, Treatment SS and error SS are computed in the usual way. However,

since our interest is in the main effect and interaction effects. We obtain their SS as

follows.

Define the effect totals by []

i.e. [A] = − [1] + [a] − [b] + [ab]

Then the SS due to any main effect or the interaction effect is obtained by multiplying

the square of the effect total by the reciprocal of 4r, where r is the common replication

number. Thus.

SS due to main effect of A = [A]2

4r with d.f. = 1;

SS due to main effect of B = [B]2

4r with d.f. = 1;

SS due to interaction effect of AB = [AB]2

4r with d.f. = 1;

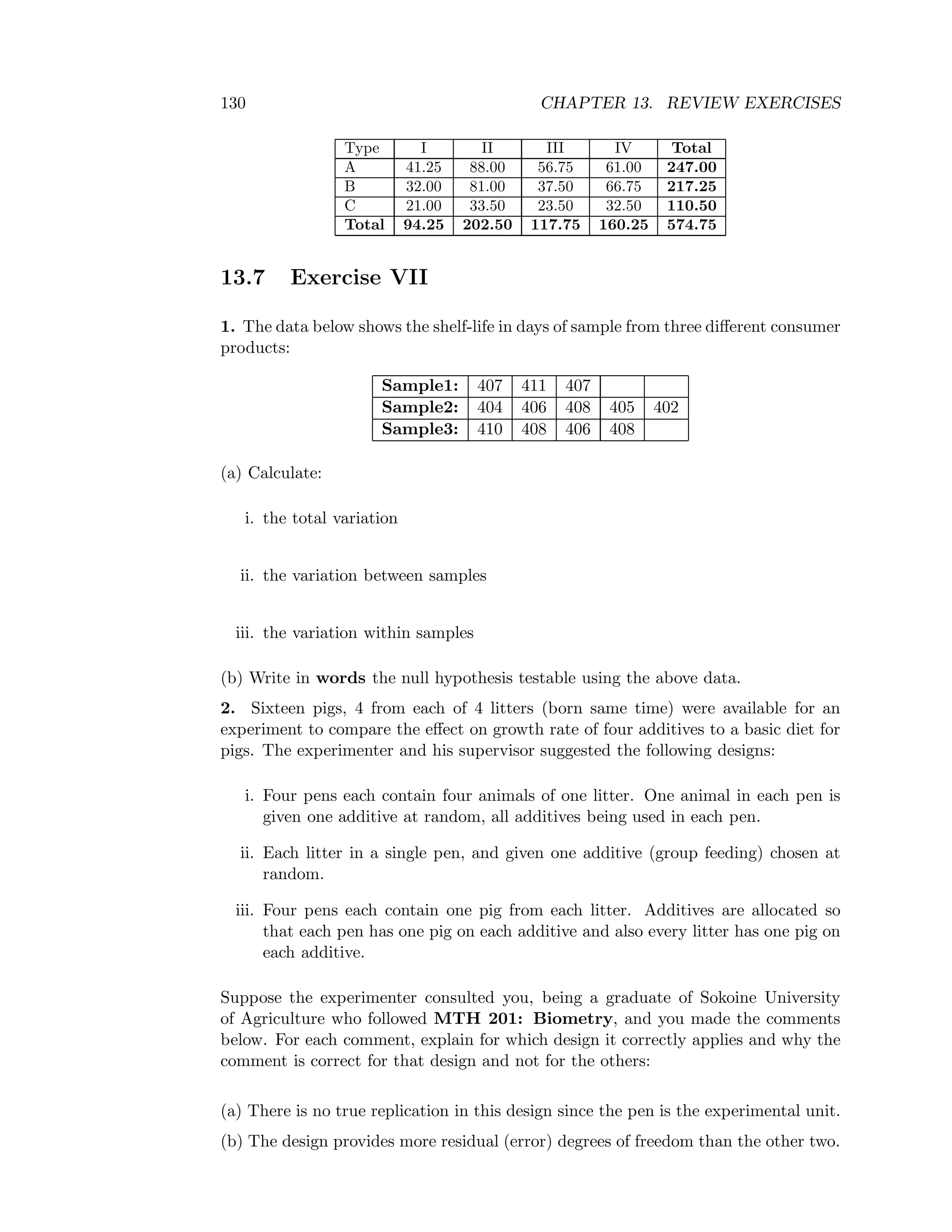

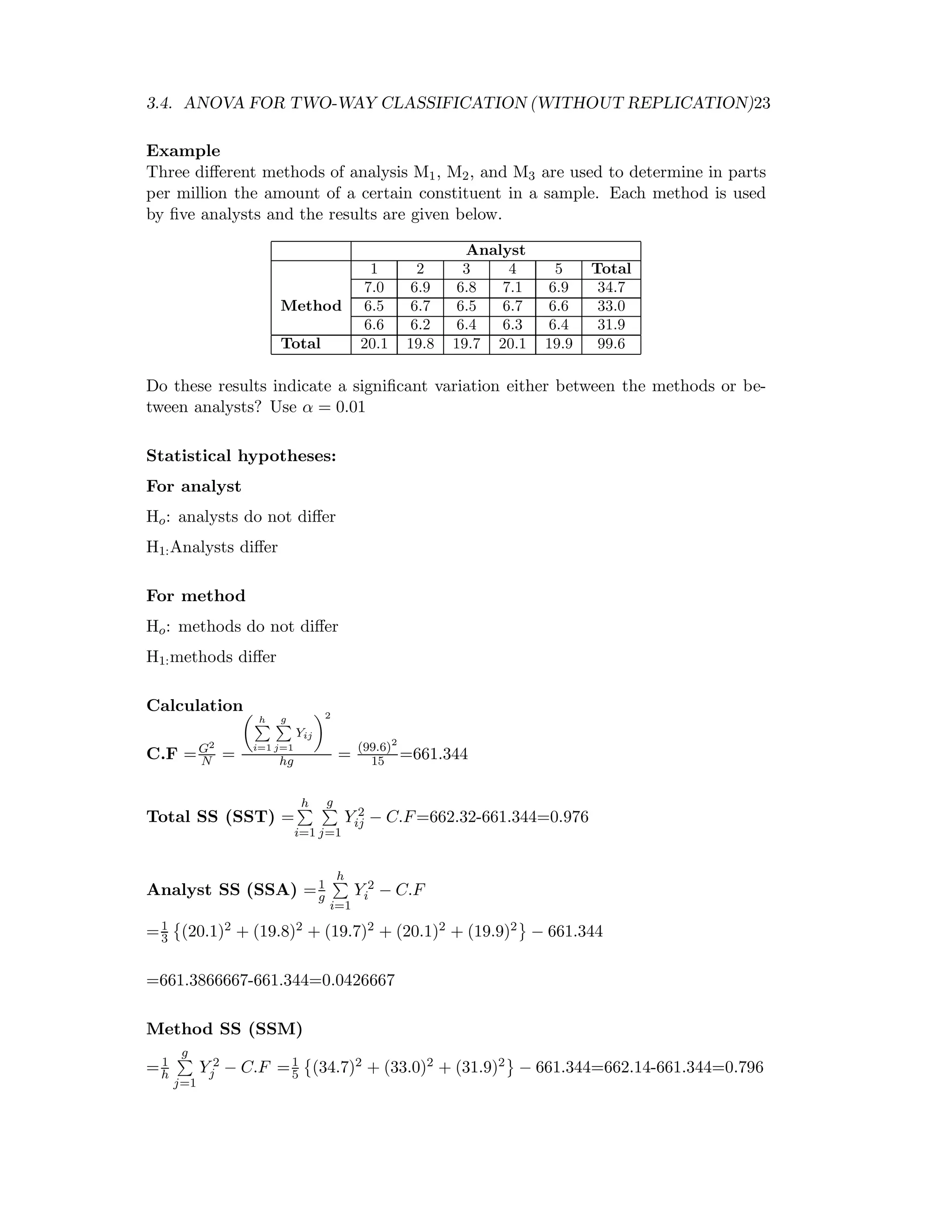

With this model, the analysis of variance table would be as follows:

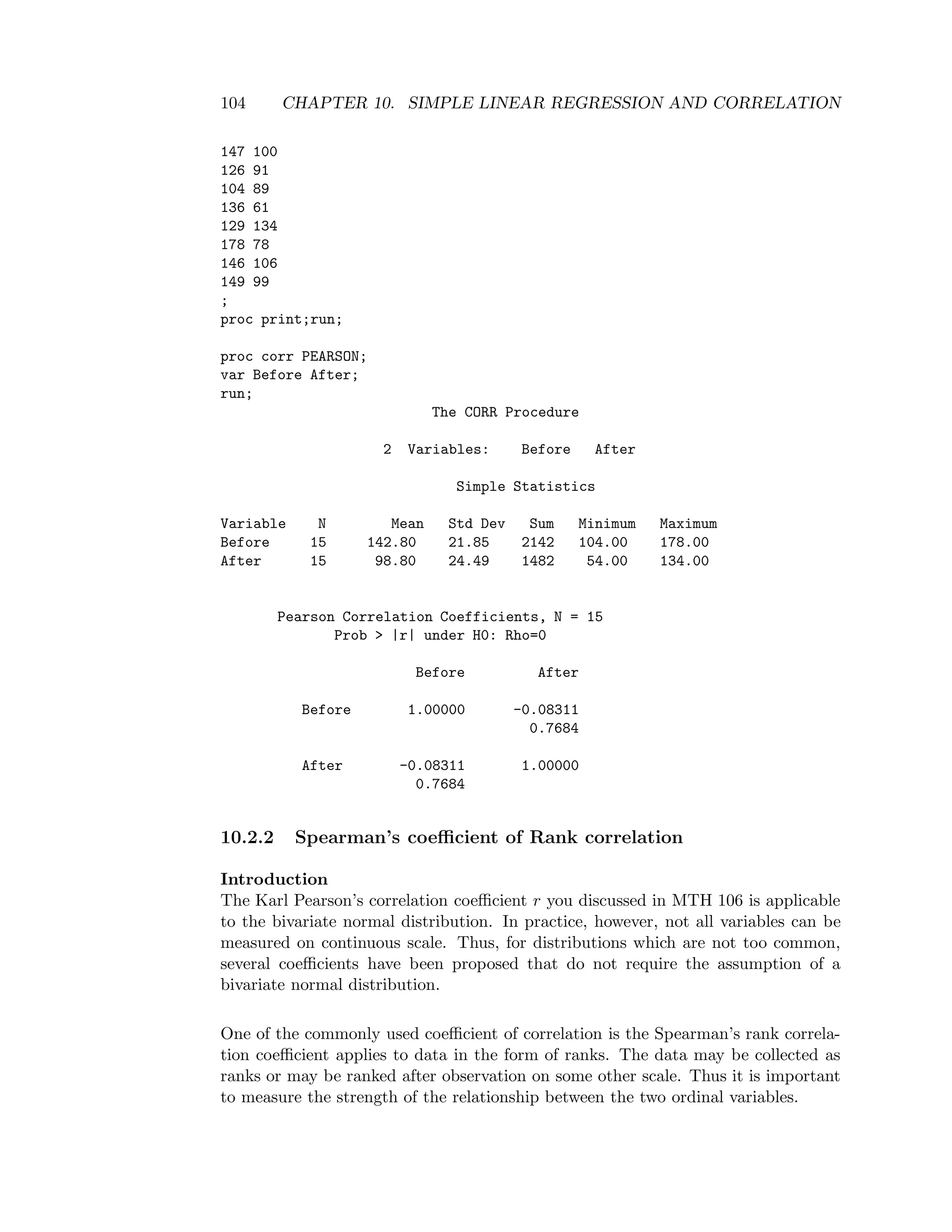

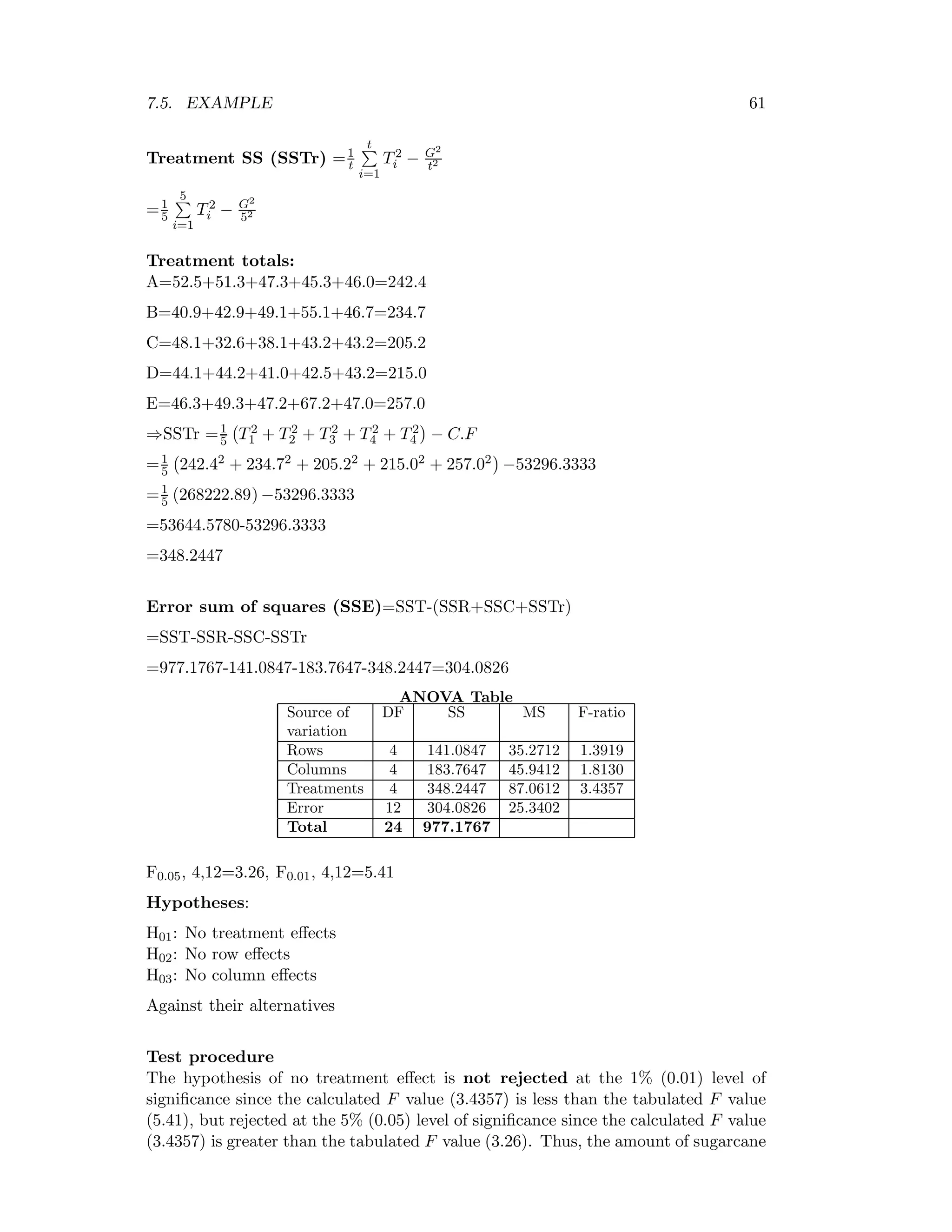

Table 8.1: ANOVA table for a 22 experiment in r randomised blocks

Source of Variation d.f. S.S. M.S. F-ratio

Blocks r - 1 SS (Blocks) MS (Blocks) MS(Blocks)

Treatments

Main effect A 1 [A]2

4r MSA MSA/MSE

Main effect B 1 [B]2

4r MSB MSB/MSE

Interaction AB 1 [AB]2

4r MS(AB) MS(AB)/MSE

Error 3(r - 1) By subtraction MSE

Total 4r- 1 SST - -

Note: the total D.F for a randomised block design is rt-1. Where r and t are

respectively the replication number and the treatments in the RBD. Since in the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-77-2048.jpg)

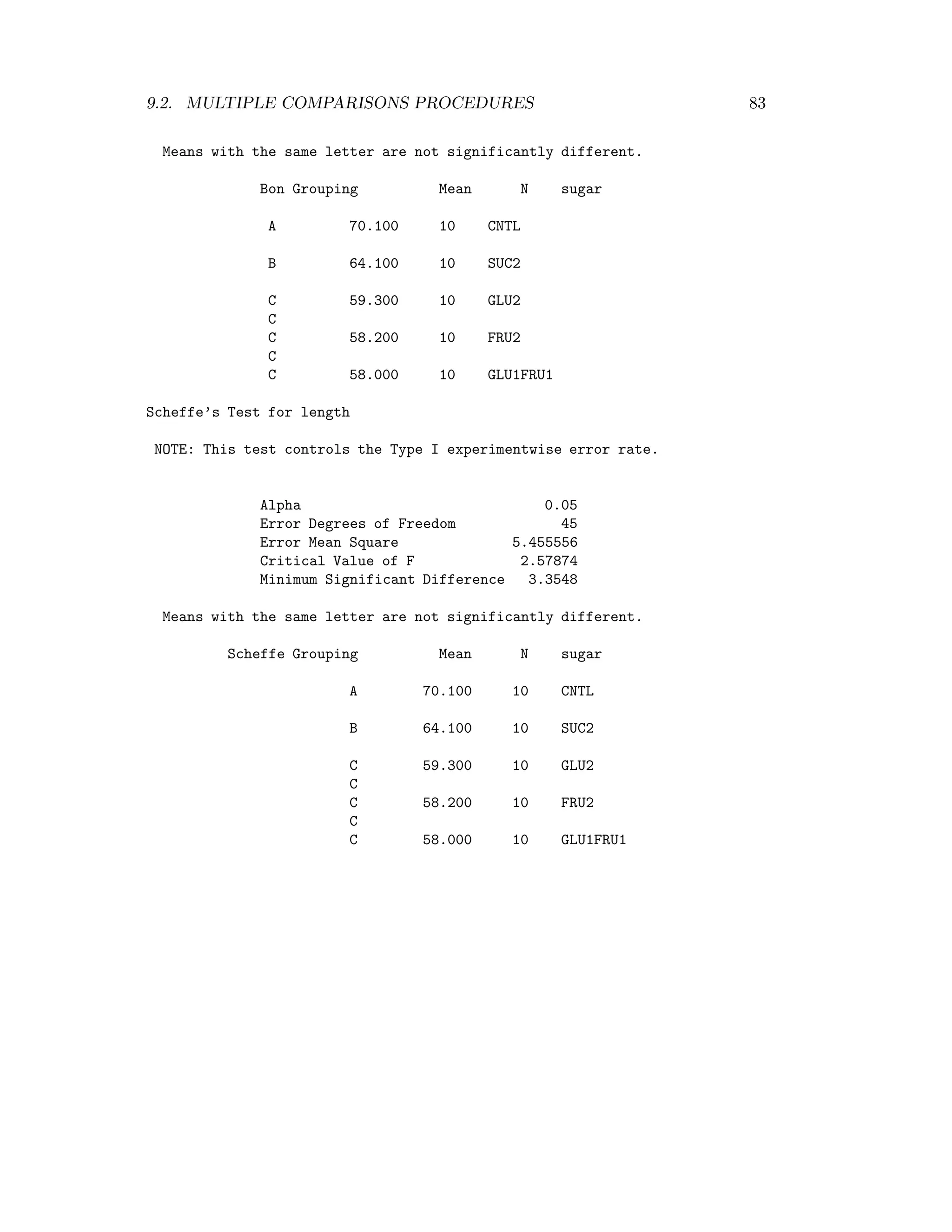

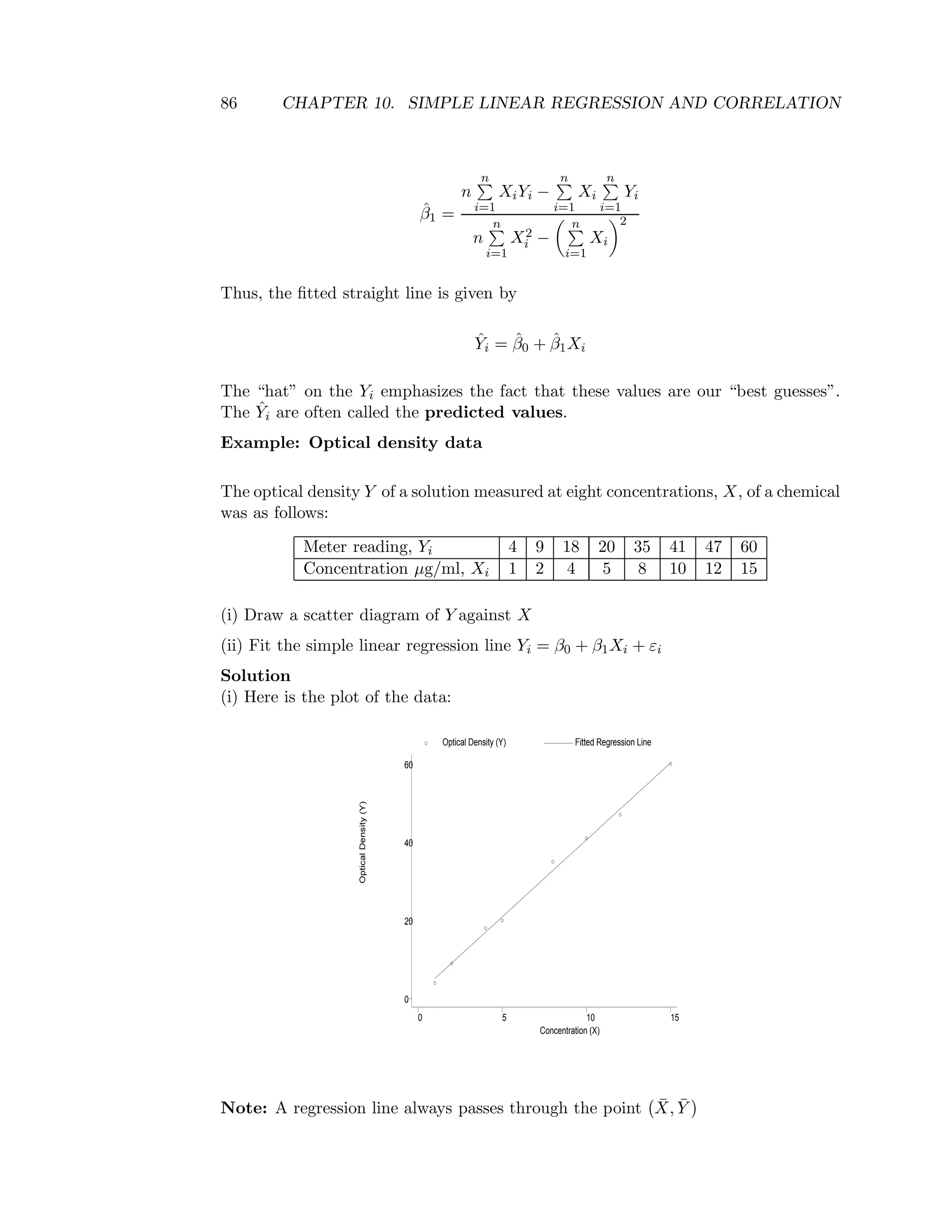

![72 CHAPTER 8. FACTORIAL EXPERIMENTS

The general formula for sum of squares of the effect is

[effect]2

2nr

where n is the number of factors in the experiment and r the replication number

(blocks).

Example:

A 22 experiment in six randomised blocks was conducted in order to obtain an idea

of the interaction: Spacing × number of seedlings per hole, along with the effects of

different types of spacing and different numbers of seedlings per hole, while adopting

the Indian method of cultivation. The levels of the two factors are:

S :

80cm spacing in between,

10cm spacing in between,

N :

3 seedlings per hole,

4 seedlings per hole.

The field plan and yield of dry Aman paddy (in kg) are as follows.

(1) s ns n

117 106 109 114

ns (1) s n

114 120 117 114

(1) n s ns

111 117 114 106

ns n s (1)

93 121 112 108

ns s (1) n

75 97 73 38

(n) (1) ns s

58 81 105 117

Analyse the data to find out if there are significant treatment effects – main or

interaction.

To find or computes the sum of squares for main effects and interaction effect, we

first find the effect totals:

First we compute the treatment totals. For each of the four treatment combinations

we sum the corresponding observations in all six blocks. For example, for treatment

n we have 114 + 114 + 117 + 121 + 38 + 58 which are observations from blocks

I, II, III, IV, V and VI respectively. This total is 562. Similarly, summing all

corresponding observations for the other treatments we have:

[ns]=607, [s]=663, [1]=610

Therefore, we obtain the effect totals as follows:

[N] = [n] + [ns] − [s] − [1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-79-2048.jpg)

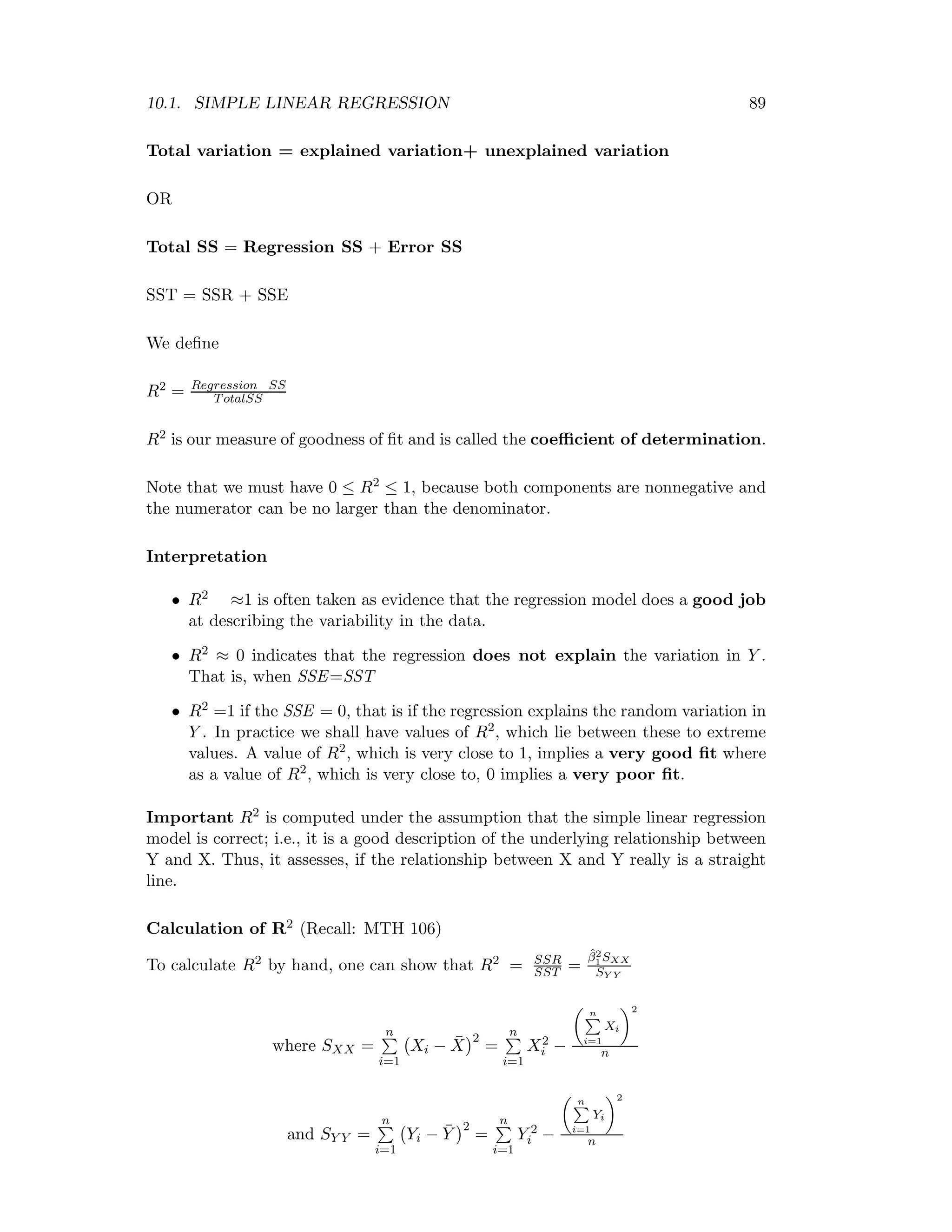

![8.6. TESTS OF SIGNIFICANCE OF FACTORIAL EFFECTS 73

= 562 + 607 – 663 – 610

= 1169 – 1273

= - 104

[S] = [s] − [n] + [ns] − [1]

= 663 – 562 + 607 – 610

= 98

[NS] = − [n] − [s] + [ns] + [1]

= 562 - 663 + 607 + 610

= 1225 + 1217

= -8

Thus, SS due to N = (−104)2

24 = 250.667;

SS due to S = (98)2

24 = 400.167;

SS due to NS = (−8)2

24 = 2.667;

We next perform the randomised block analysis.

The six block totals are:

Block I: 446, Block II: 465, Block III: 448, Block IV: 439, Block V : 283, Block VI:

361

Grand total G = 446 + . . . + 361 = 2442; N = rt=6×4= 24

⇒Correction factor (C.F.) = (2442)2

24 = 5963364

24

= 248, 473.5

Uncorrected total sum of square

i j

y2

ij= 259,024.

⇒Total sum of square (SST) =

i j

y2

ij-C.F = 259.024 – 248,473.5

= 10,550.5

Block sum of square (SSB) =1

4

6

j=1

Y 2

j − C.F = (446)2

+...+(361)2

4 − 248, 473.5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-80-2048.jpg)

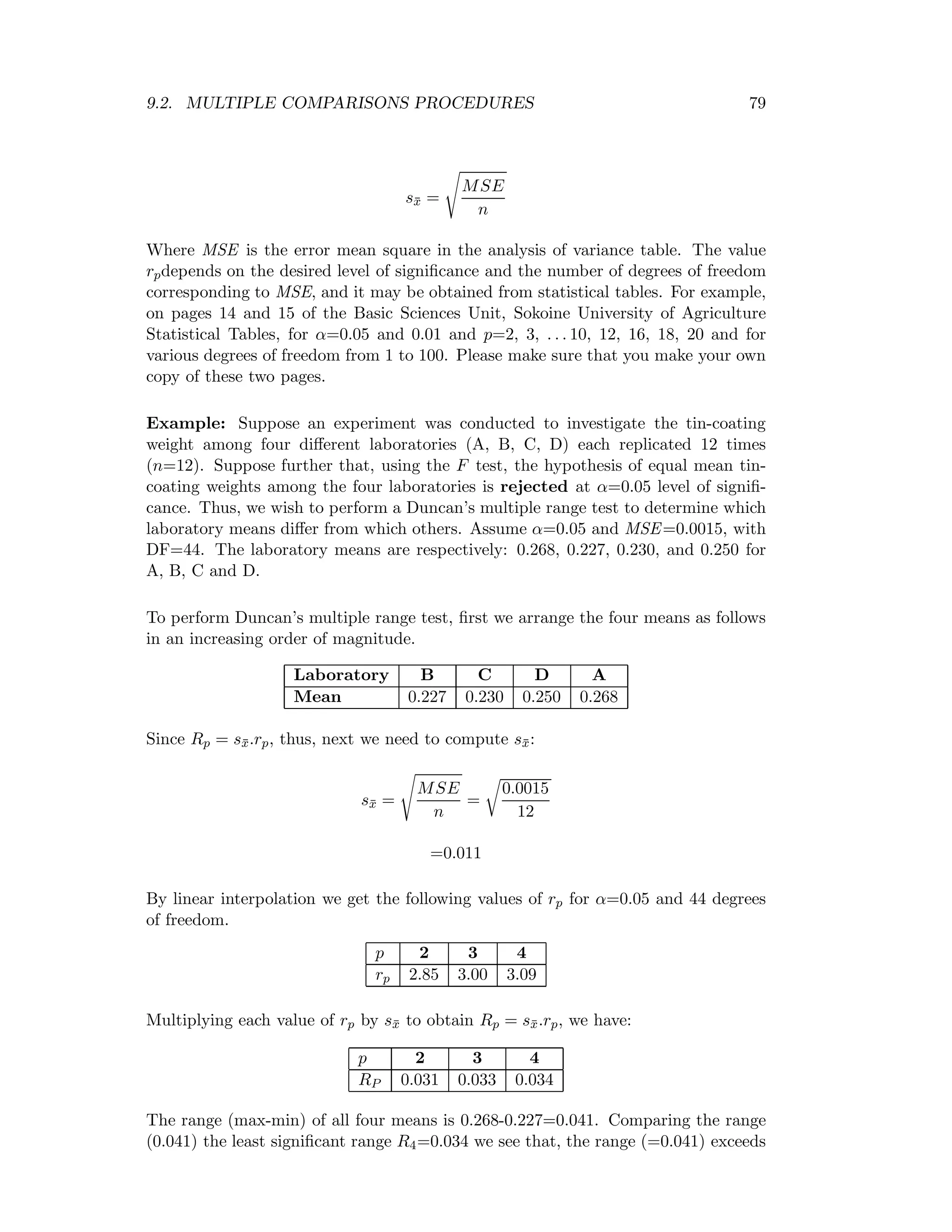

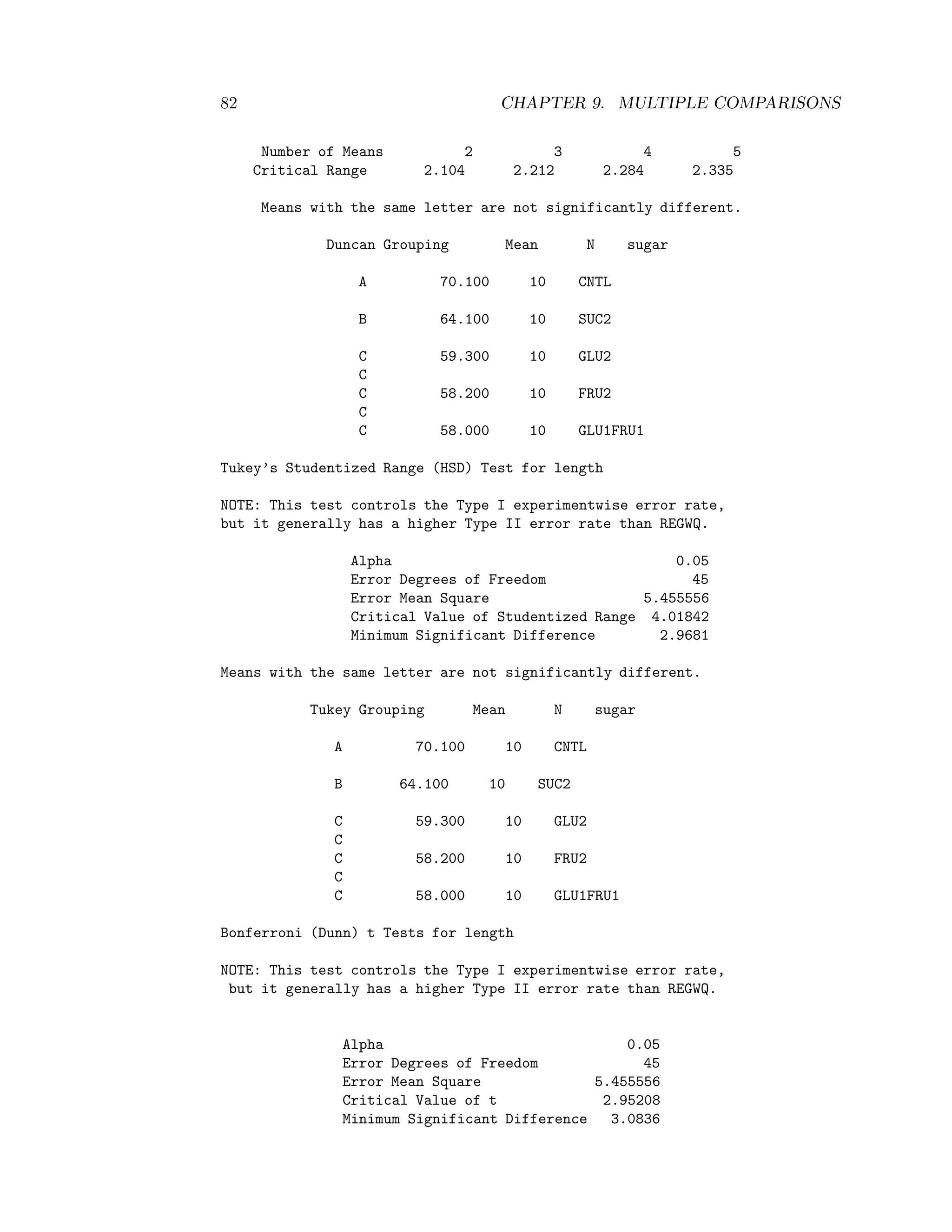

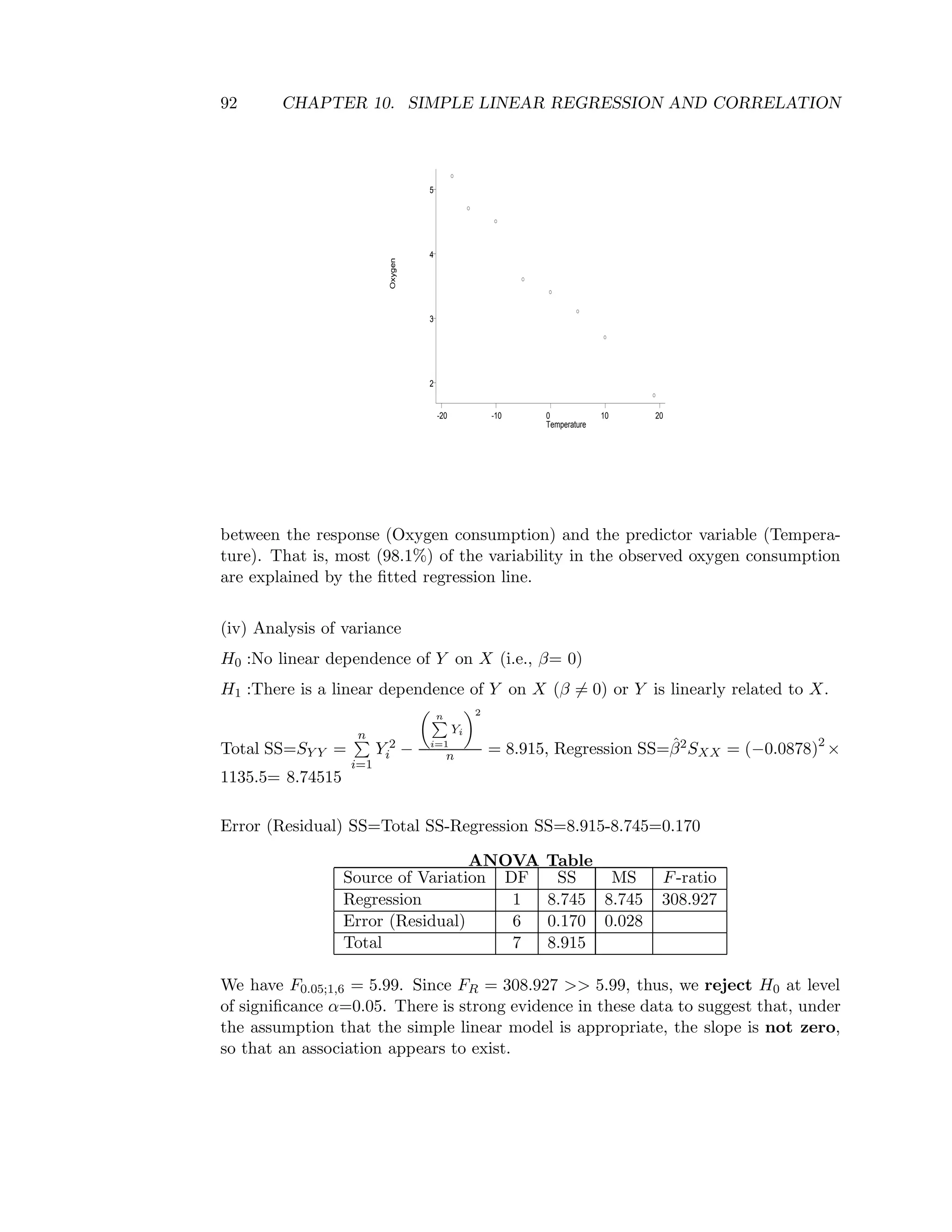

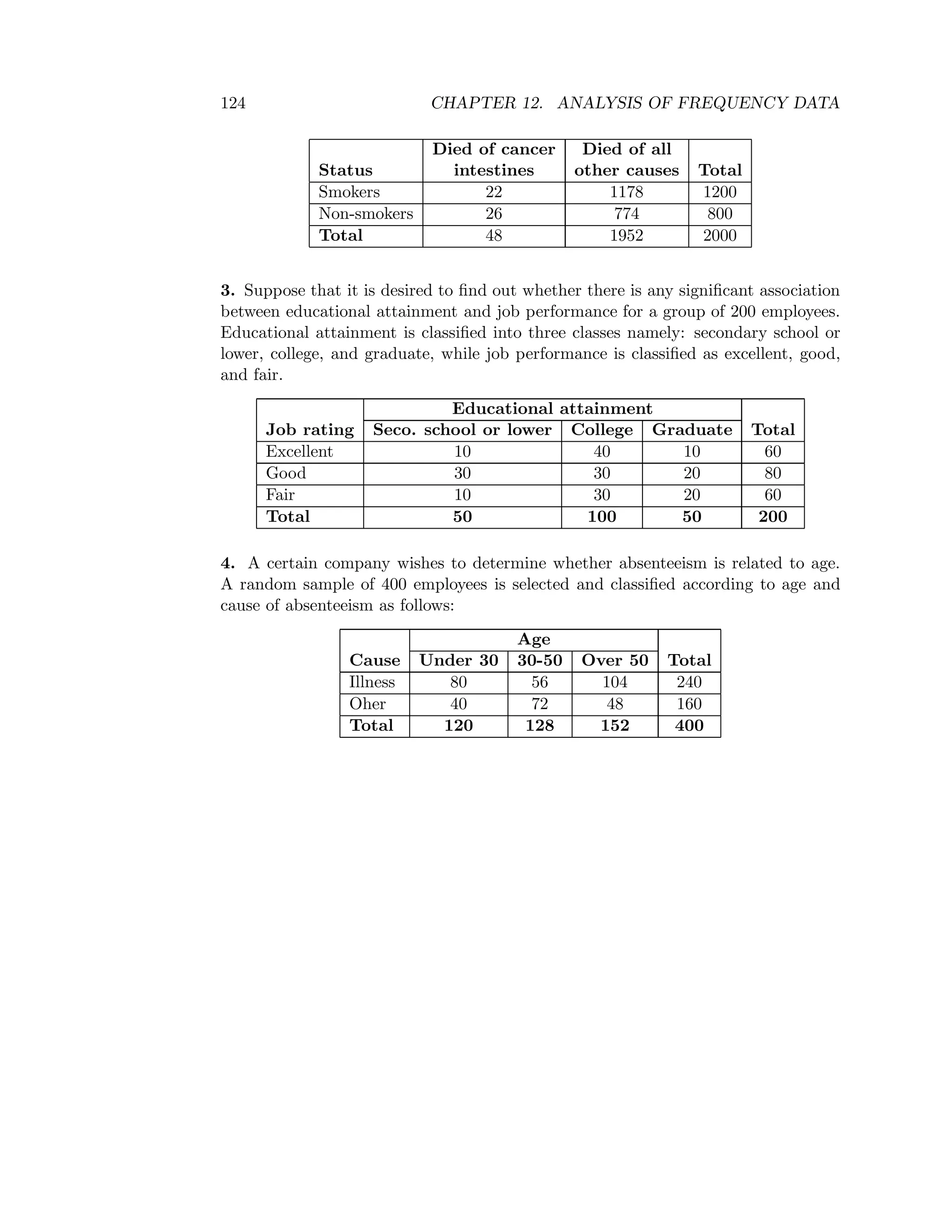

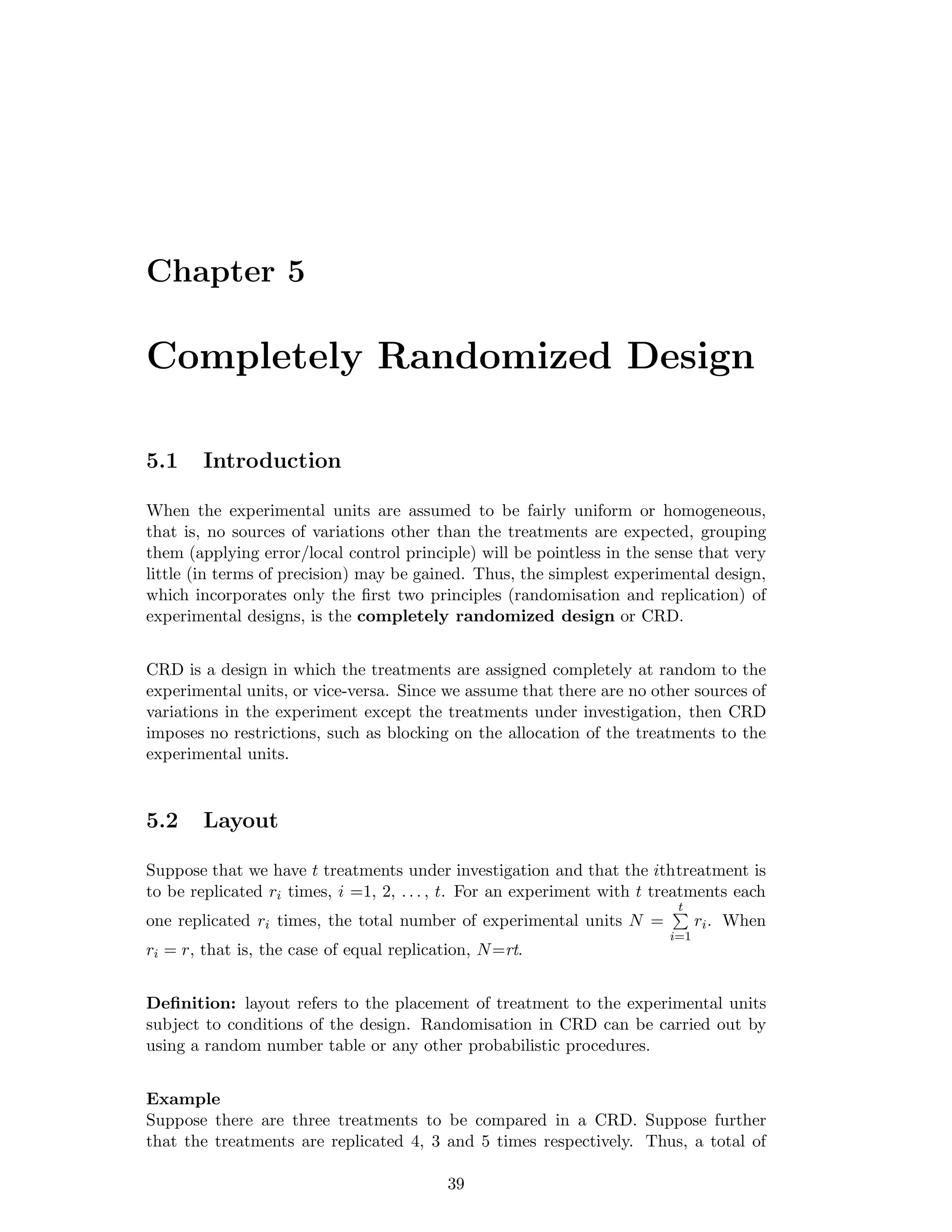

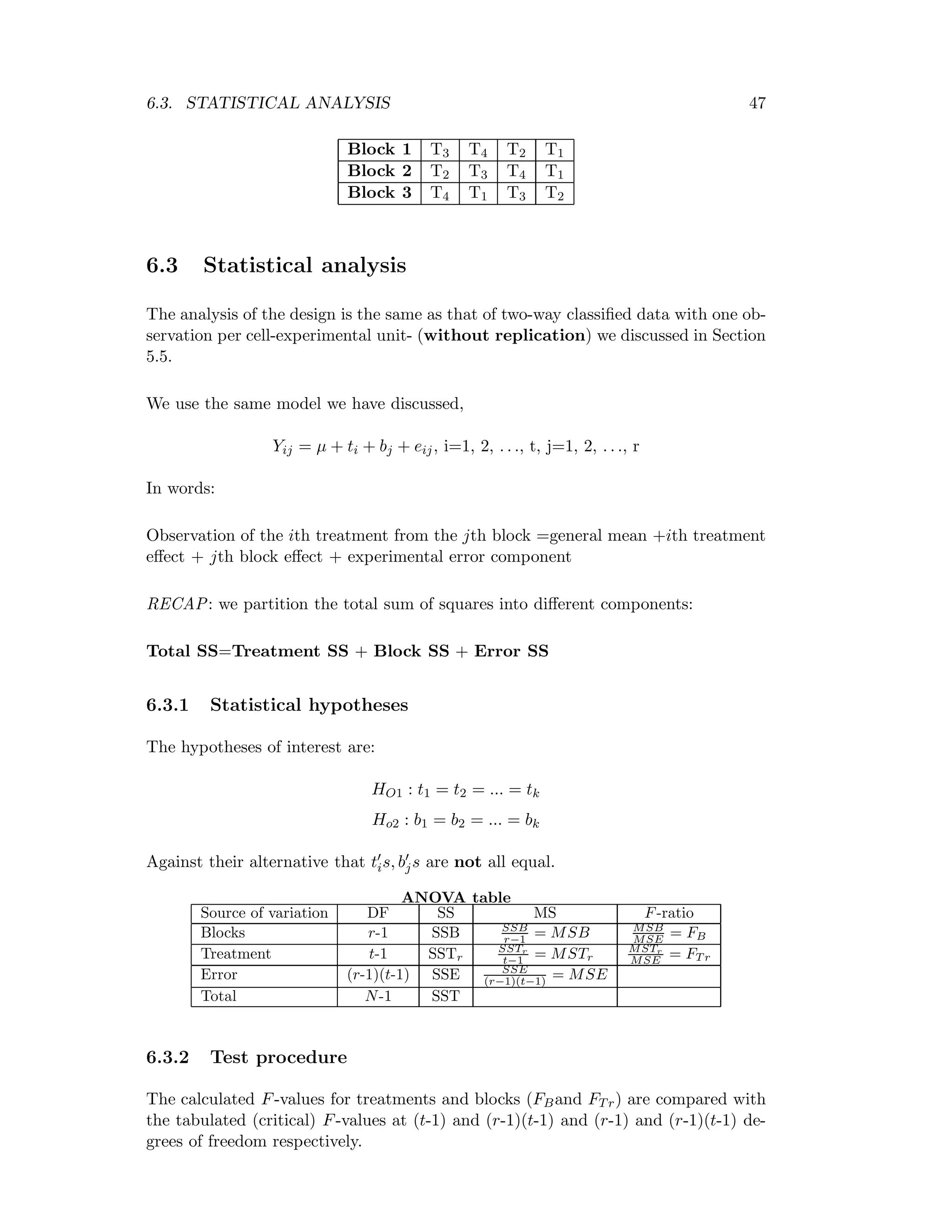

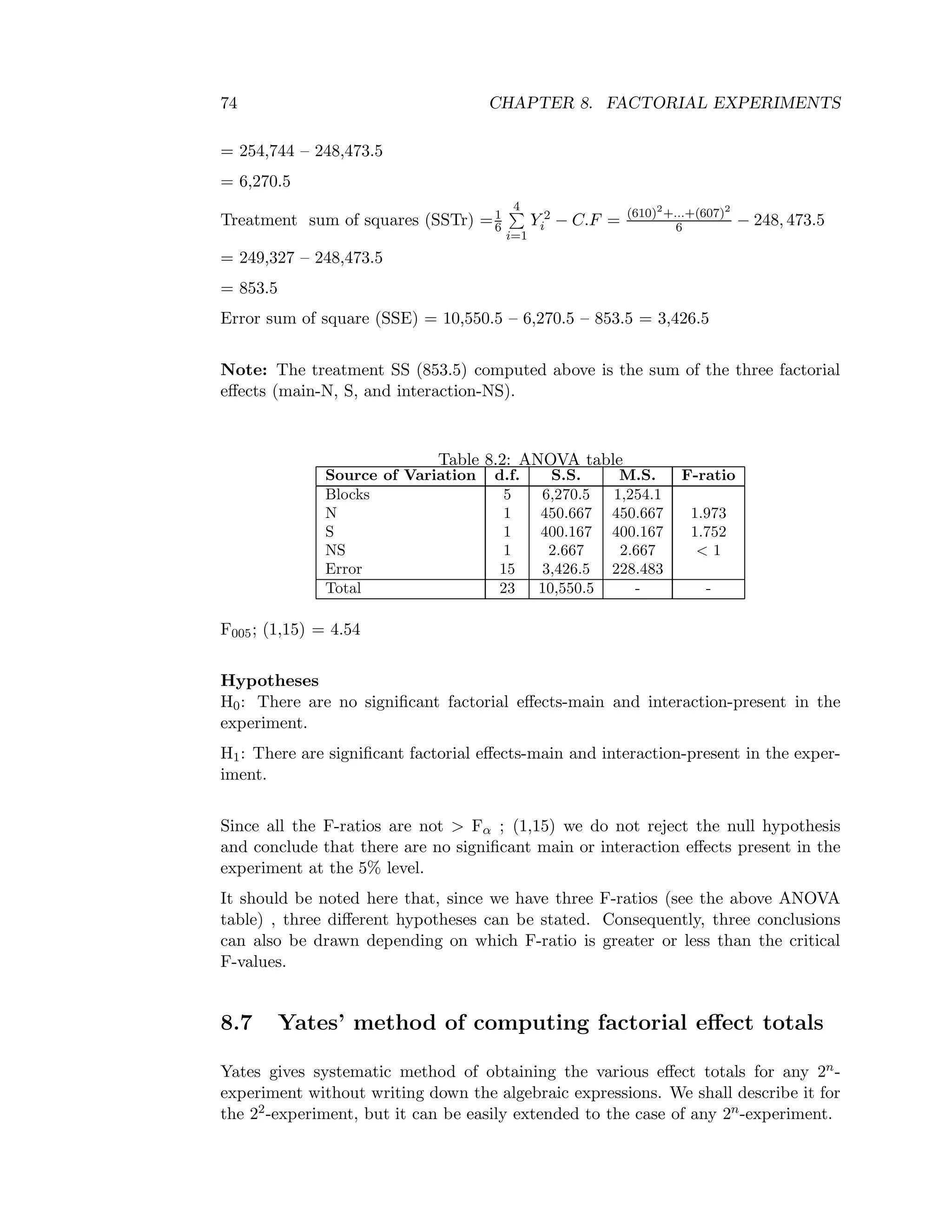

![8.7. YATES’ METHOD OF COMPUTING FACTORIAL EFFECT TOTALS 75

The steps are as follows:

• Write down the four (4) treatment combinations systematically in the first

column, stating with the treatment combination (1) and then introducing the

letters a, b in turn. After introducing a letter, write down its combination

with all the previous treatment combinations and then introduce a new letter.

Repeat this until all the letters (n letters in the case of a 2n-experiment) have

been exhausted.

• Write down the treatment totals from all the replicates in the second column

against appropriate treatment combination.

• Put the values in column 2 into consecutive pairs (i.e. 1 and 2, 3 and 4, etc).

The obtain column three by adding the values of these pairs up to half way

and subtracting the pairs in the other half (the second subtracting the first in

the pairs).

• Break the values in the third column into consecutive pairs and put the sums

and differences members of these pairs in order in the fourth column.

For a 22-experiment, the fourth column values give the factorial effect totals corre-

sponding to the treatment combination occurring in the corresponding positions of

the first column.

For a 2n-experiment, repeat n times the operations of column 3 and 4. The procedure

ends at the (n+n) th column, the first entry in the last column being always the grand

total.

Treatment Treatment Third column Fourth column Effect Totals

combination Totals

(1) [1] [1] + [a] [1]+[a]+[b]+[ab] Grand Total

a [a] [b] + [ab] [a]-[1]+[ab]-[b] [A]

b [b] [a]-[1] [b]+[ab]-[1]-[a] [B]

ab [ab] [ab]-[b] [ab]-[b]-[a]+[1] [AB]

Exercises:

1. A 22 factorial experiment i.e. 2 factors, varieties and manures and each at 2 levels

was carried out in a randomised block design with 3 replicates. The yields given in

the following table are hypothetical.

Treatment combination

Replicates v1m1 v1m2 v2m1 v2m2

5 7 8 10

4 4 7 5

6 4 9 12

Using Yates’ method Perform the analysis of variance test for the significance of the

effects of varieties and manure and their interaction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mth201-171116073355/75/Mth201-COMPLETE-BOOK-82-2048.jpg)