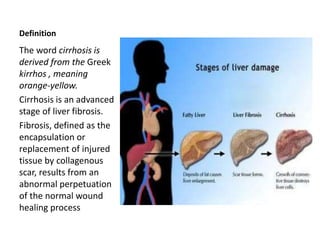

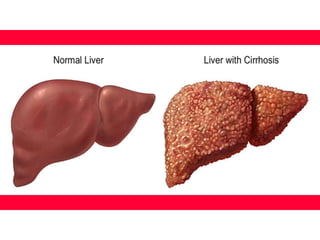

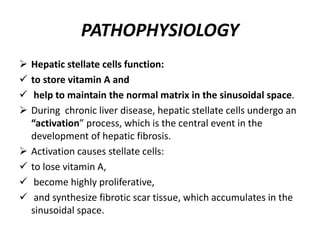

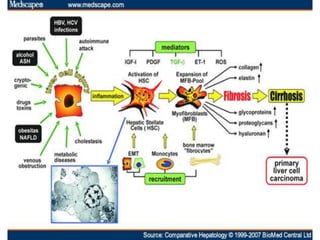

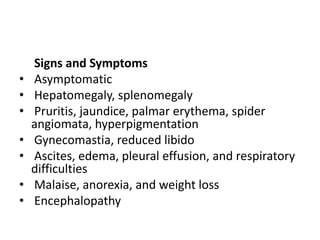

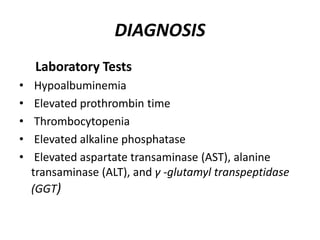

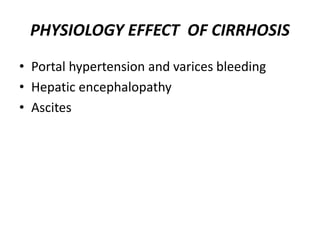

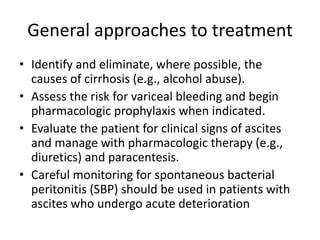

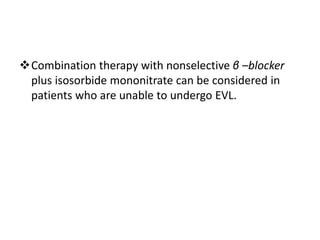

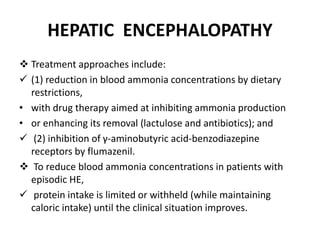

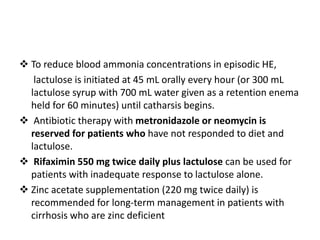

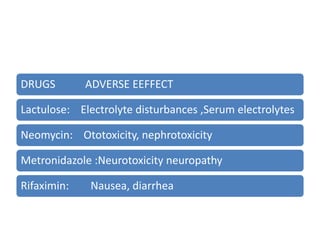

The document details cirrhosis, an advanced stage of liver fibrosis, including its definition, causes, pathophysiology, symptoms, diagnostic tests, and treatment strategies. Key treatment approaches involve managing portal hypertension, preventing variceal bleeding, and addressing complications like hepatic encephalopathy and ascites. The document also highlights clinical controversies regarding optimal therapies and the management of adverse effects associated with treatment.