This document discusses dose adjustment in patients with renal impairment. It covers several key topics:

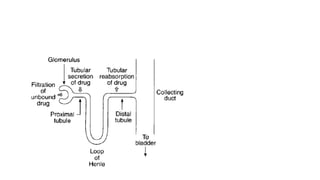

1. The kidney's role in regulating fluids, electrolytes, waste removal, and drug excretion. Impaired kidney function affects drug pharmacokinetics.

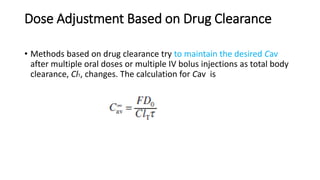

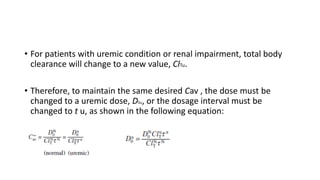

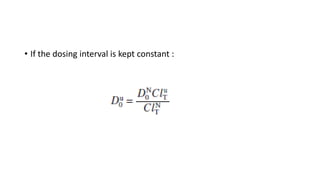

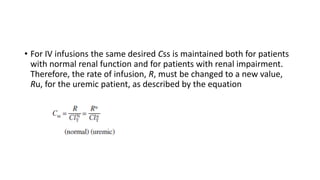

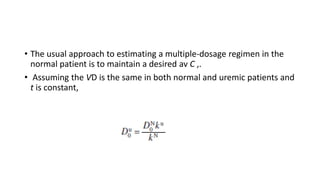

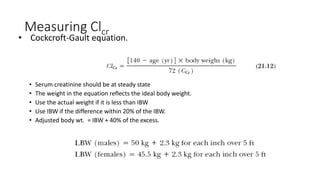

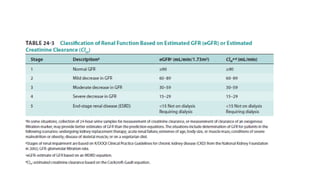

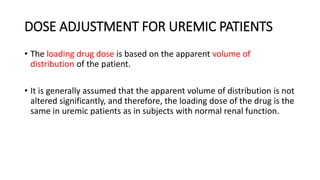

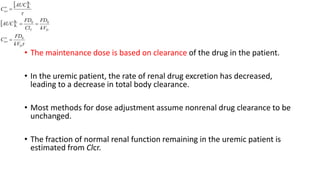

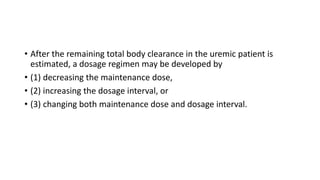

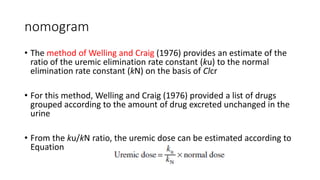

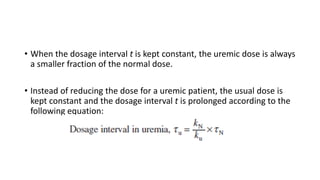

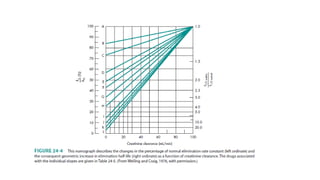

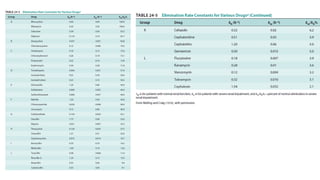

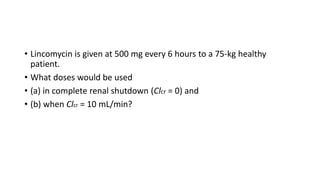

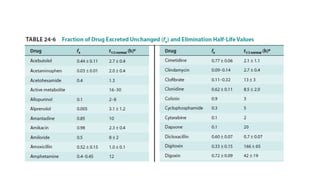

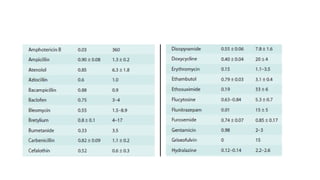

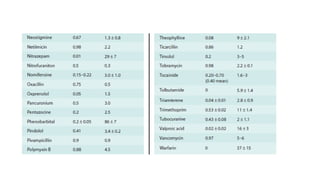

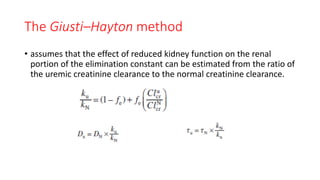

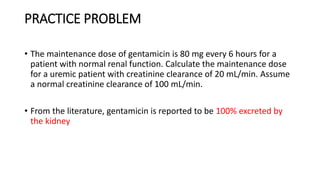

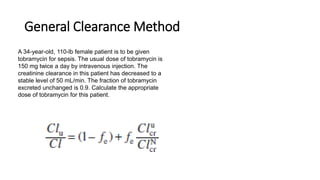

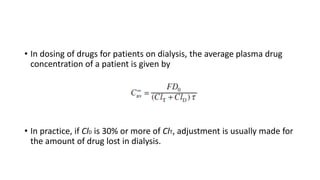

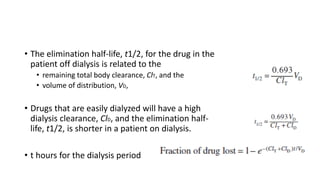

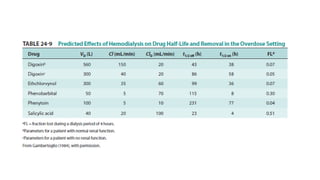

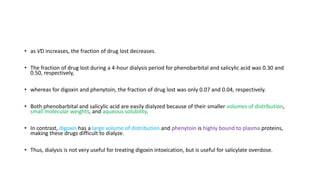

2. Approaches for dose adjustment based on estimating remaining renal function and drug clearance. Dose, dosing interval, or both may be adjusted to maintain therapeutic drug levels.

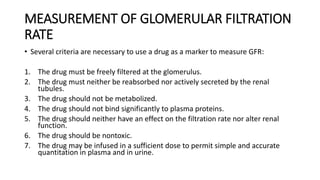

3. Methods for estimating glomerular filtration rate and measuring kidney function using markers like inulin, creatinine, and urea. Creatinine clearance is commonly used in clinical practice.

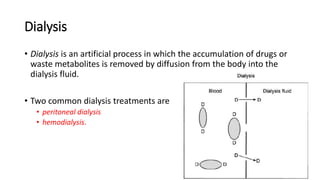

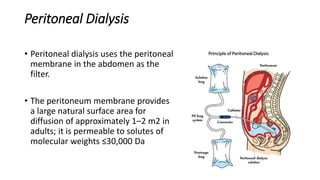

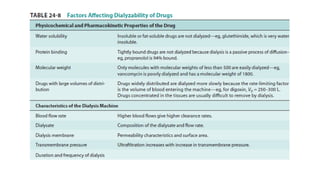

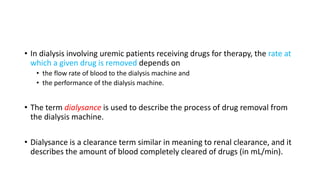

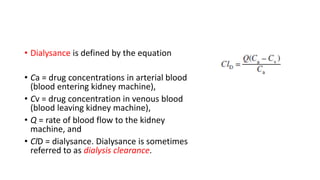

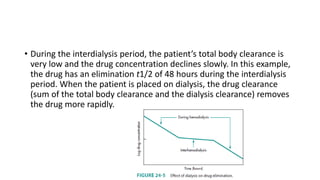

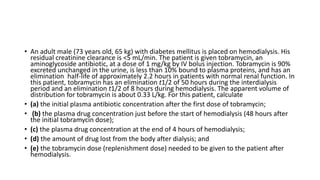

4. Considerations for dose adjustment in patients on dialysis, as