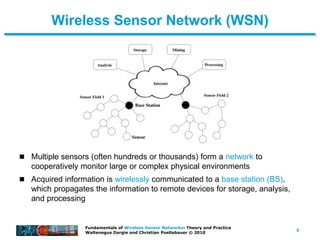

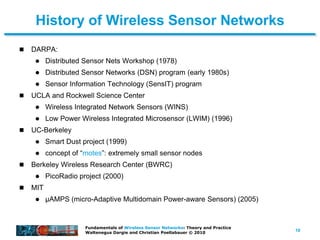

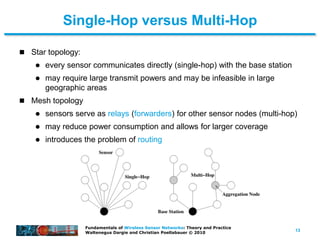

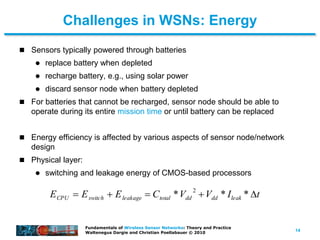

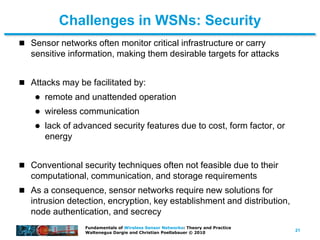

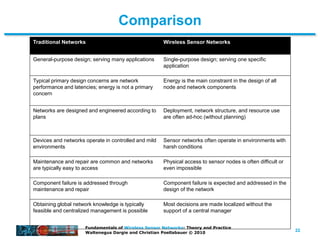

This document provides an overview of key topics in wireless sensor networks that will be covered in a course, including motivations, applications, node architecture, operating systems, networking layers, power management, time synchronization, localization, security, and programming. It discusses the history of wireless sensor networks and defines them as networks of multiple sensor nodes that cooperatively monitor environments. It also outlines several challenges in designing wireless sensor networks, such as limited energy, self-management without human intervention, and difficulties of wireless communication like signal attenuation over distance.