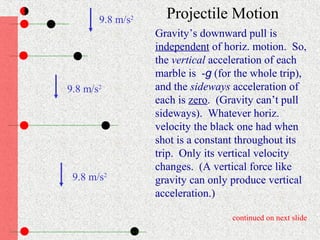

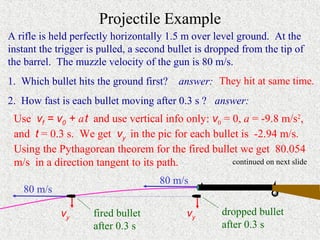

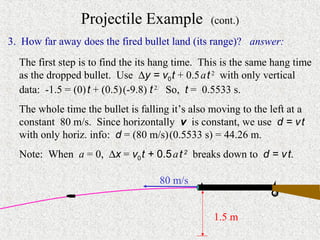

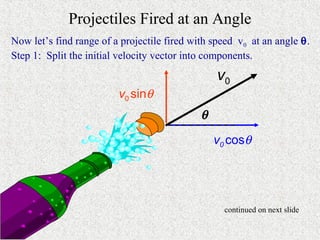

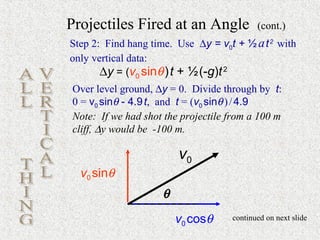

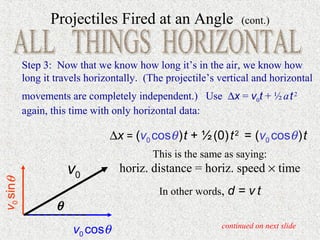

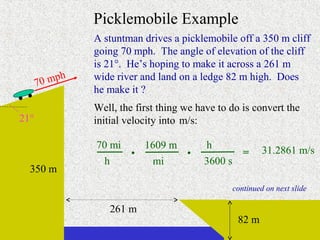

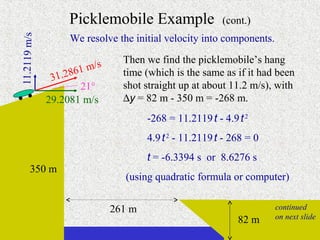

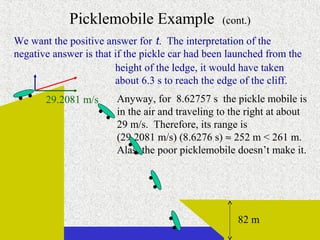

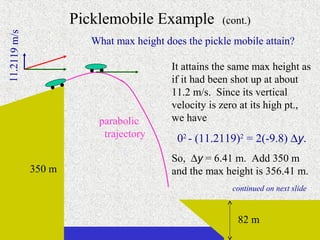

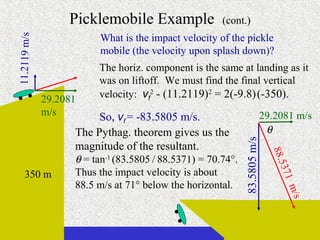

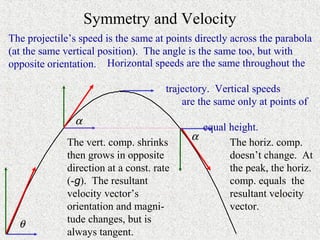

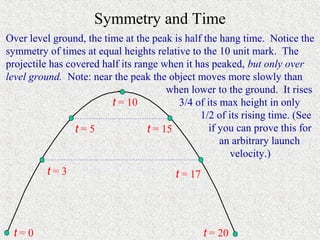

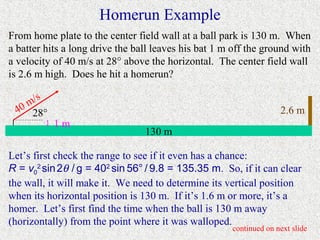

The document discusses projectile motion, describing how objects moving through the air are affected by gravity. It explains that gravity only affects vertical motion, not horizontal motion, so horizontally a projectile maintains a constant velocity if no other forces are present. Examples are provided to demonstrate how to calculate the time of flight, range, and landing point of projectiles fired at various angles and velocities.

![Parabolic Proof

A projectile is shot with speed v0 at an angle θ. Its vertical

position is given by y = (v0 sinθ ) t + ½ (-g) t 2. Here y is the

dependent quantity, and t is the independent quantity. Everything

else is a constant.

The projectile’s horizontal position is given by x = (v0 cosθ ) t.

Only x and t are variables, and t = x / (v0 cosθ ). Let’s substitute

this for t in the equation for y:

y = (v0 sinθ ) t + ½ (-g) t 2

y = (v0 sinθ ) [x / (v0 cosθ )] - ½ g [x / (v0 cosθ )]2

g

y = (tanθ ) x - x2

2 v02 cos2θ

The coefficients of x and x 2 are constants. Since the leading coef.

is negative, this is the equation of a parabola opening down.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-18-320.jpg)

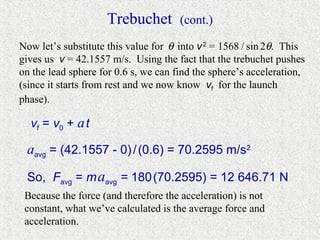

![Trebuchet (cont.)

Let t = time at impact. Horizontally: 120 = (v cosθ ) t.

Vertically: 18 = (v sinθ ) t - 4.9 t 2. Now substitute for t :

18 = (v sinθ ) [120 / (v cosθ ) ] - 4.9 [120 / (v cosθ ) ] 2

⇒ 18 = 120 tanθ - 4.9 • 14400

v2 cos2θ

From the last slide, v 2 = 1568 / sin 2θ. Substitute for v 2

into the equation above:

14400

18 = 120 tanθ - 4.9 •

1568 • cos2θ

sin 2θ

⇒ 18 = 120 tanθ - 45 sin 2θ ⇒ 6 = 40 tan θ - 15 sin 2θ

cos2θ cos2θ

continued on next slide](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-33-320.jpg)

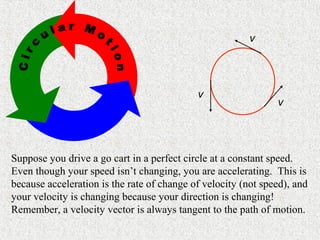

![Trebuchet (cont.)

Now we have an equation with just one variable, but it’s not an easy

one to solve. We can solve for θ by graphing the equation below and

looking for a y-intercept (in radian mode).

15 sin 2θ

y = 40 tanθ - -6

cos θ

2

10

7.5 0.4

5

0.2

2.5

-2.5 0.25 0.5 0.75 1 1.25 1.5 0.525 0.53 0.535 0.54 0.545 0.55

-0.2

-5

-7.5 -0.4

-10 Domain: [ 0, π / 2 ] Domain: [ 0.52, 0.55 ]

180°

θ = 0.5404 radians • = 30.9626°

π radians continued on next slide](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-34-320.jpg)

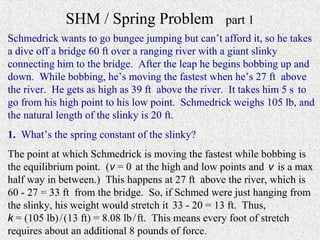

![Simple Harmonic Motion

A mass bobbing up and down on a spring undergoes

simple harmonic motion (SHM). SHM occurs whenever

a body’s position as a function of time is of the form

y = A cos [ b (t - c) ] + d. You’ll see this in trig class too.

y = vertical position (our dependent variable)

t = time (our independent variable)

|A| = amplitude (maximum distance from equilibrium)

d = vertical displacement of the equilibrium from your

reference point (point from which you measure)

m

c = phase shift (time from start of

experiment until the mass reaches equilibrium pt.

its first maximum displacement). c = 0 if experiment starts with

spring fully stretched or compressed. The period of the mass is

the amount of time it takes to bob up and down once. b is used to

determine the period. The period, T, is given by T = 2π / b. 2π is

the “normal” period of the sine & cosine functions (see next slide).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-62-320.jpg)

![sin

Sine & Cosine Graphs: y = A cos [ b (t - c) ] + d

y = cos t 3

2 period = 2π y = 1 cos[ 1(t - 0) ] + 0

1

-Pi Pi } amp = 1 A=1

-2 Pi -1 2 Pi

-2

b=1

-3 c=0

d=0

y = cos t begins at a max; y = sin t begins at

T = 2π / 1 = 2π

equilibrium. Their periods and amplitudes are the

same. Their graphs are congruent, differing only

by a 90° horizontal shift.

period = 2π y = 1 sin[ 1(t - 0) ] + 0

y = sin t 3

2

1

A=1

} amp = 1 b=1

-2 Pi -Pi -1 Pi 2 Pi

c=0

-2

-3

d=0

T = 2π / 1 = 2π](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-63-320.jpg)

![Cosine graph: Amplitude y = A cos [ b (t - c) ] + d

3

y = cos t The leading coefficient

2 A=1m

1 determines the amplitude,

-Pi Pi

-2 Pi 2 Pi

which equals |A|. If A is

-1

-2

negative, the graph is

-3 reflected about the time

3

axis. For the red graph,

y = 2 cos t 2

A=2m

1 our mass is pushed up,

compressing the spring

-2 Pi -Pi Pi 2 Pi

-1

2 m and is released at time

-2

-3

zero. In the green graph,

it’s pulled down 1.5 m and

3 released at time zero.

y = -1.5 cos t 2 A = 1.5 m

1

Note: all graphs have the

same period or 2π, and

-2 Pi -Pi -1 Pi 2 Pi none has a phase (horiz.)

-2

shift or a vertical shift.

-3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-64-320.jpg)

![Cosine graph: Period y = A cos [ b (t - c) ] + d

3 T = 2π / b

y = cos t 2 2π

1 The bigger b is, our

-Pi Pi

“scrunch factor,” the more

-2 Pi 2 Pi

-1

scrunched up the graph

-2 b = 1 s-1

-3 gets. The red graph

completes 3 cycles in same

y = cos 3 t 3

2π / 3

2 time the blue graph does

1 one, and red’s period is 3

-2 Pi -Pi -1 Pi 2 Pi times shorter. So, the mass

-2

b = 3 s-1 in the red graph goes up and

-3 down 3 times more often.

3 The green graph completes

y = cos 0.5 t 2 half as many cycles as blue

1 b = ½ s-1 and its mass has twice the

-2 Pi -Pi -1 Pi 2 Pi period. Note: b’s units

-2 cancel t’s.

4π

-3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-65-320.jpg)

![Cosine graph: vertical displacement y = A cos [ b (t - c) ] + d

3

y = cos t 2 Adding or subtracting

-Pi

1

Pi outside of the cosine

-2 Pi -1 2 Pi function shifts the graph

-2

d=0 vertically. The dotted

-3 lines are lines of

y = cos t + 1.5 3 symmetry. For our mass

2

on a spring, this is where

1

it’s in equilibrium (where

-2 Pi -Pi -1 Pi 2 Pi the spring is neither

-2 d = 1.5 stretched nor compressed).

-3

For the red graph, the

3 mass is in equilibrium 1.5

y = cos t - 0.5 2 d = -0.5 meters above the point

1

from which we chose to

-2 Pi -Pi -1 Pi 2 Pi

make our measurements.

-2

-3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-66-320.jpg)

![Cosine graph: Phase Shift y = A cos [ b (t - c) ] + d

3

y = cos t 2 Adding or subtracting inside

1 c=0 the cosine function shifts the

-2 Pi -1 2 Pigraph horizontally. (Adding

-2 shifts it left, subtracting

-3 right.) Like the mass in the

c = -1.2 s 3 blue graph, the red mass was

y = cos (t + 1.2)

2

compressed 1 m and then

}

1

released, but the clock was

-2 Pi -Pi -1 Pi 2 Pistarted 1.2 s after it had

-2 reached max compression.

-3

The green mass was also

3 c = 0.9 s compressed 1 m and

y = cos (t - 0.9) 2

released, but the clock was

}

1

started 0.9 s before the mass

-2 Pi -Pi Pi 2 Pi

-1

reached max compression.

-2

-3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-67-320.jpg)

![bridge

SHM / Spring Problem part 2

y = 60 ft

2. If the clock starts when he jumps off the bridge, write

Schmedrick’s position as a function of time using the river

as a reference point.

Ignoring air resistance, a mass on a spring undergoes

SHM (derived in advanced physics). Hence we can use

y = A cos [ b (t - c) ] + d. Our task, then, is to find H y = 39 ft

A, b, c, and d. d = 27 ft since the equilibrium pt, Eq,

is 27 ft above our reference position. The high pt, H, is

Eq y = 27 ft

given to be 39 ft. This is 12 ft above Eq, so A = 12 ft,

and the low pt, L, is 12 ft below Eq. Since it takes 5 s

for him to go from H to L, his period is 10 s. So, L y = 15 ft

T = 2π / b ⇒ b = 2π / (10 s) = 0.628 s-1. If Schmedrick

had been at H or L at t = 0, c would be zero. But the clock

starts early (when y = 60 ft), so let’s figure out

how long it takes him to fall to H (assume free fall). y=0

continued on next slide river](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-69-320.jpg)

![bridge

SHM / Spring Problem part 2 (cont.)

If we’d like to continue working in feet, we can’t use y = 60 ft

9.8 m/s2 for g. Instead we use its equivalent: 32 ft / s2.

He falls 21 ft to H. Thus, -21 = (0) t + 0.5 (-32) t 2

⇒ t = 1.146 s, and this is our c value. (This is only

an approximation, since the spring begins stretching after

he falls 20 ft.) Putting it all together, we have:

H y = 39 ft

y(t) = 12 cos [ 0.628 (t - 1.146) ] + 27

where t is the time in seconds from the instant he

jumps, and y is his height above the water in feet. Eq y = 27 ft

Note: This formula only works for t > 1.146 s, since

that’s when SHM begins.

L y = 15 ft

Check by plugging in some values into the function

(using radian mode in the calculator):

y(1.146) = 12 cos [0] + 27 = 12(1) + 27 = 39 ft. (H)

y(6.146) = 12 cos [0.628 (5) ] + 27 = 12 (-1) + 27 y=0

= 15 ft. (L) So he’s at L 5 s after he’s at H. river](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-70-320.jpg)

![SHM / Spring Problem parts 3 & 4

3. How high up is Schmedrick 14 s into the experiment?

y (14) = 12 cos [0.628 (14 - 1.146) ] + 27 = 24.4 ft. (When we

calculated b, we used 2π rather than 360° for the “normal” period

of the cosine function, so we must put our calculators in radian

mode.)

4. At what times is he 30 ft above the river?

He can only be at one position at a particular time, but he can be at a

particular position at many different times. (This is the nature of a

function.) Thus, 30 = 12 cos [ 0.628 (t - 1.146) ] + 27, and we must solve

for t. First isolate the cosine function by subtracting 27 and dividing by

12: 0.25 = cos [0.628 (t - 1.146) ]. Think of the quantity in the

brackets as an angle. We want to know what angles have a cosine of

0.25. One angle is cos-1 (0.25) = 1.318 (radians). But this is only one

of an infinite number of angles whose cosine is 0.25.

continued on next slide](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-71-320.jpg)

![y

SHM / Spring Problem part 4 (cont.)

P1 On a unit circle (radius 1, center at origin):

cosθ left & right (green)

sinθ up & down (brown)

θ

x tanθ slope (of red)

One angle in which cosθ = 0.25 is 1.318

radians ≈ 75.5° (in Q I). Another

occurs at 4.965 ≈ 284.5° (in Q IV). To

P2 get to P1 or P2 from the origin, you must

go 0.25 units to the right. Thus, both

angles have the same cosine of 0.25. Negative angles and angles over

2π (or 360°) that terminate at P1 or P2 will also have a cosine of 0.25.

These angles are 1.318 + 2nπ and 4. 965 + 2nπ, where n = 0, ±1, ±2,

±3, …. Ex: when n = 5, cos[1.318 + 2(5)π ] = 0.25. Here we’ve gone

around the circle 5 times and stopped at P1. continued on next slide](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-72-320.jpg)

![SHM / Spring Problem part 4 (cont.)

We are in the process of solving 0.25 = cos [0.628 (t - 1.146) ]. Our

“angle” is 0.628 (t - 1.146). Therefore,

0.628 (t - 1.146) = 1.318 + 2nπ t = 1.146 + (1.318 + 2nπ) / 0.628

or or

0.628 (t - 1.146) = 4. 965 + 2nπ t = 1.146 + (4.965 + 2nπ) / 0.628

We only want t values > 1.146 s (when SHM begins). Substituting in

for n, we get t = 3.245 s, 13.250 s, 23.255 s, … or

t = 9.052 s, 19.057 s, 29.062 s, …

These are all the times when Schmedrick is 30 ft above the water. The

top row lists times when he’s on his way down. The bottom row lists

times when he’s bouncing back up. The difference between consecutive

times on a given row is 10 s (neglecting some slight compounded

rounding error), which is the period of his motion. That is, every 10 s

he is at the same position moving in the same direction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap7-130128145229-phpapp02/85/Chap7-73-320.jpg)