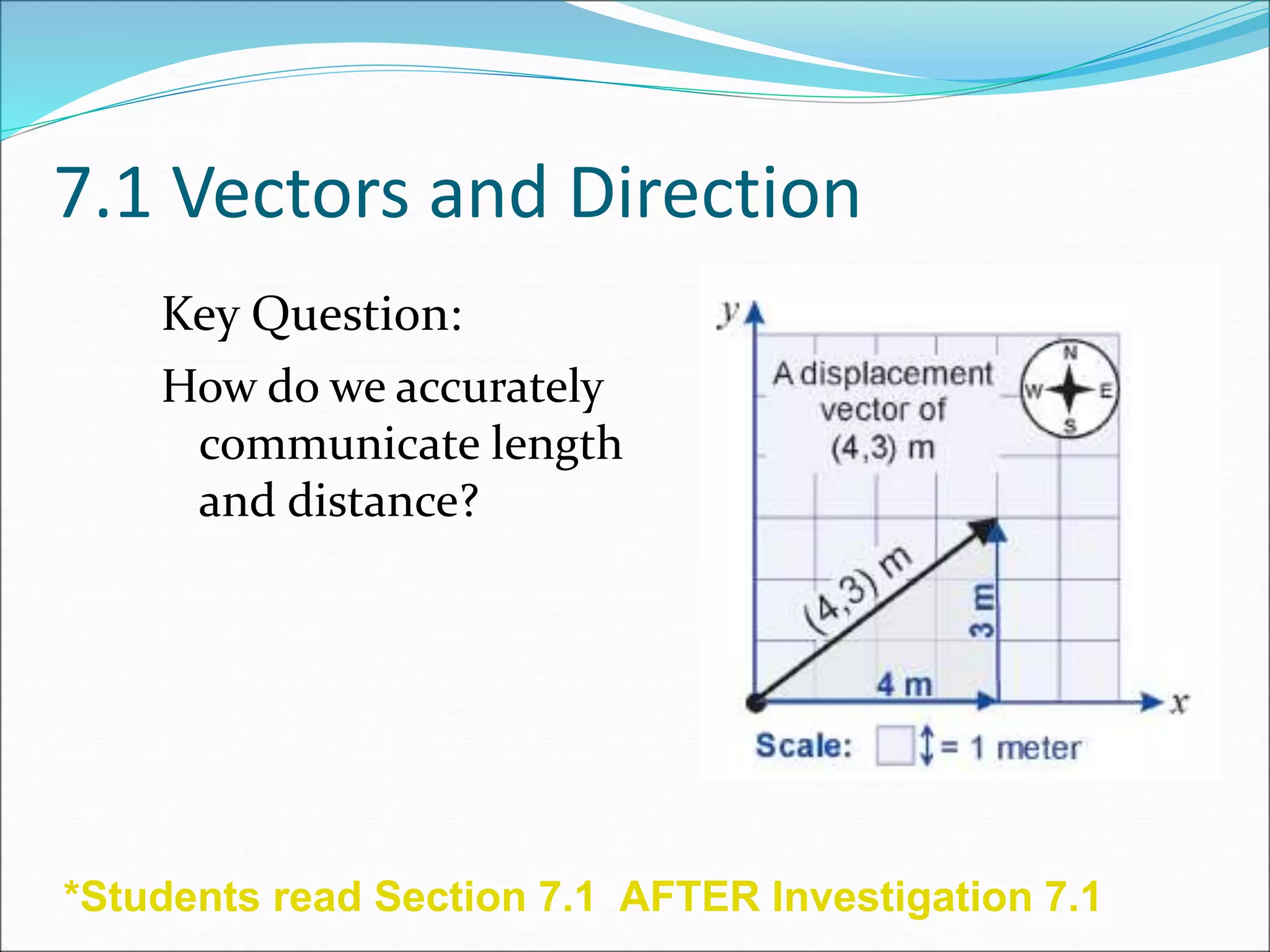

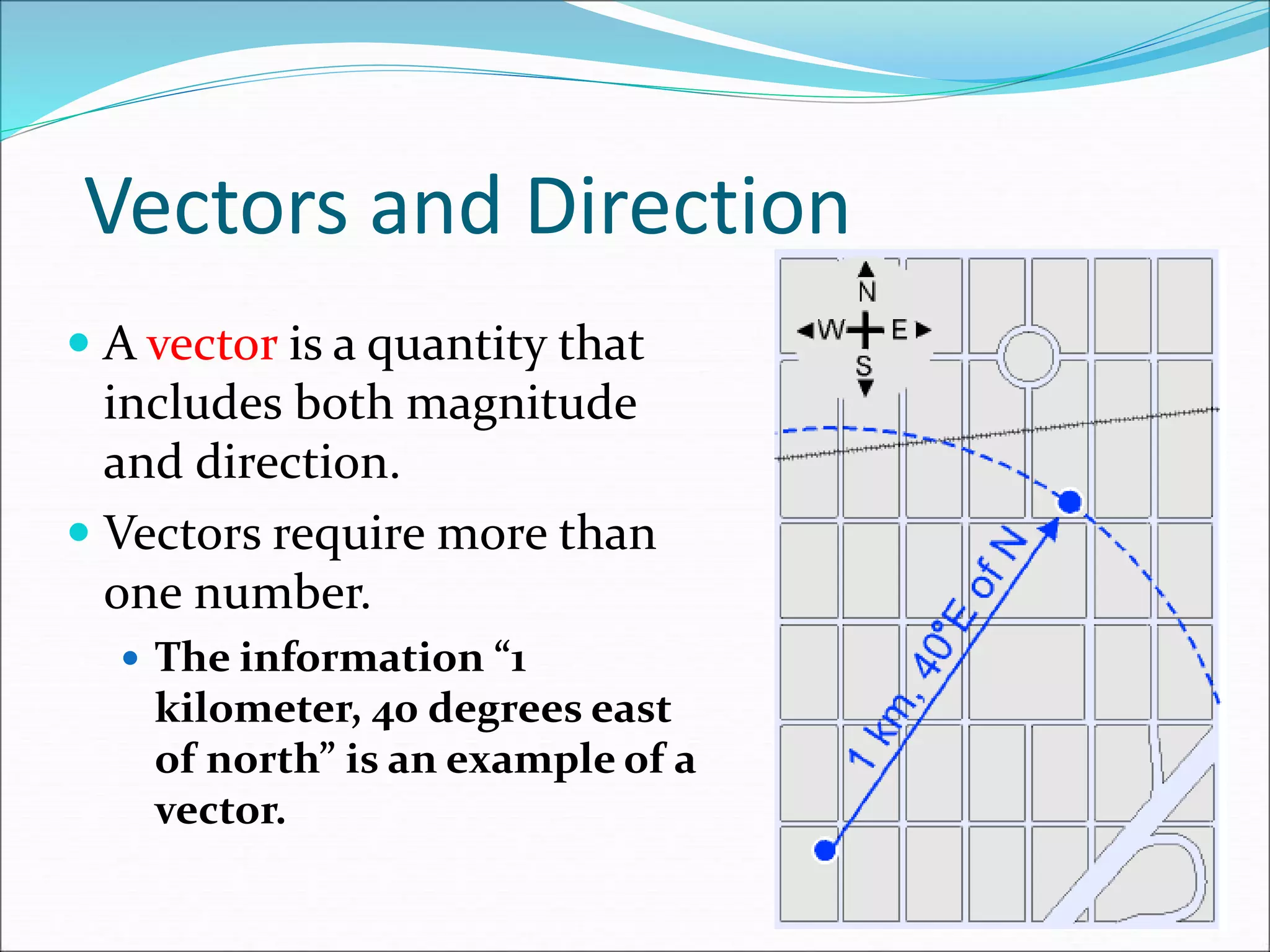

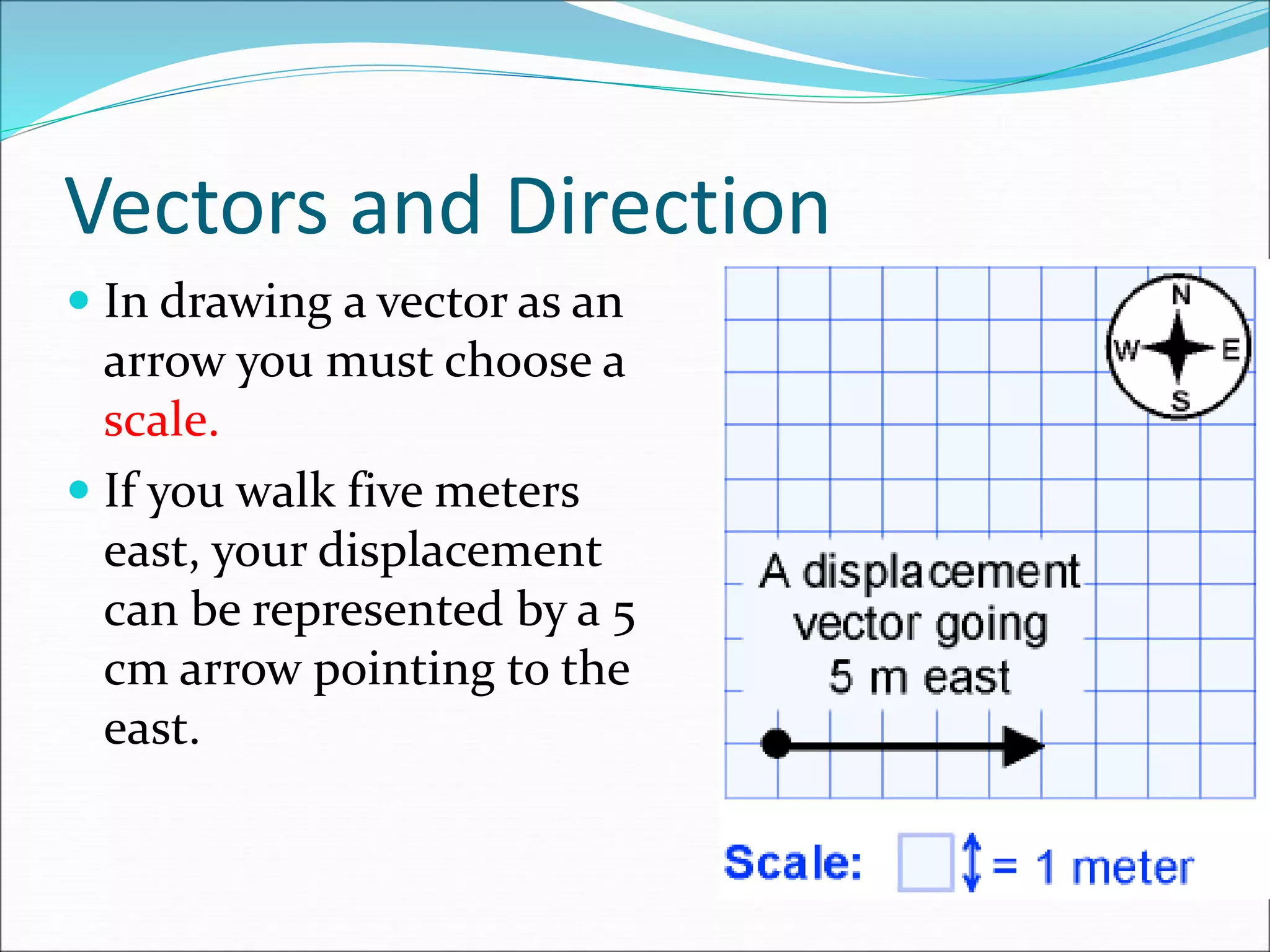

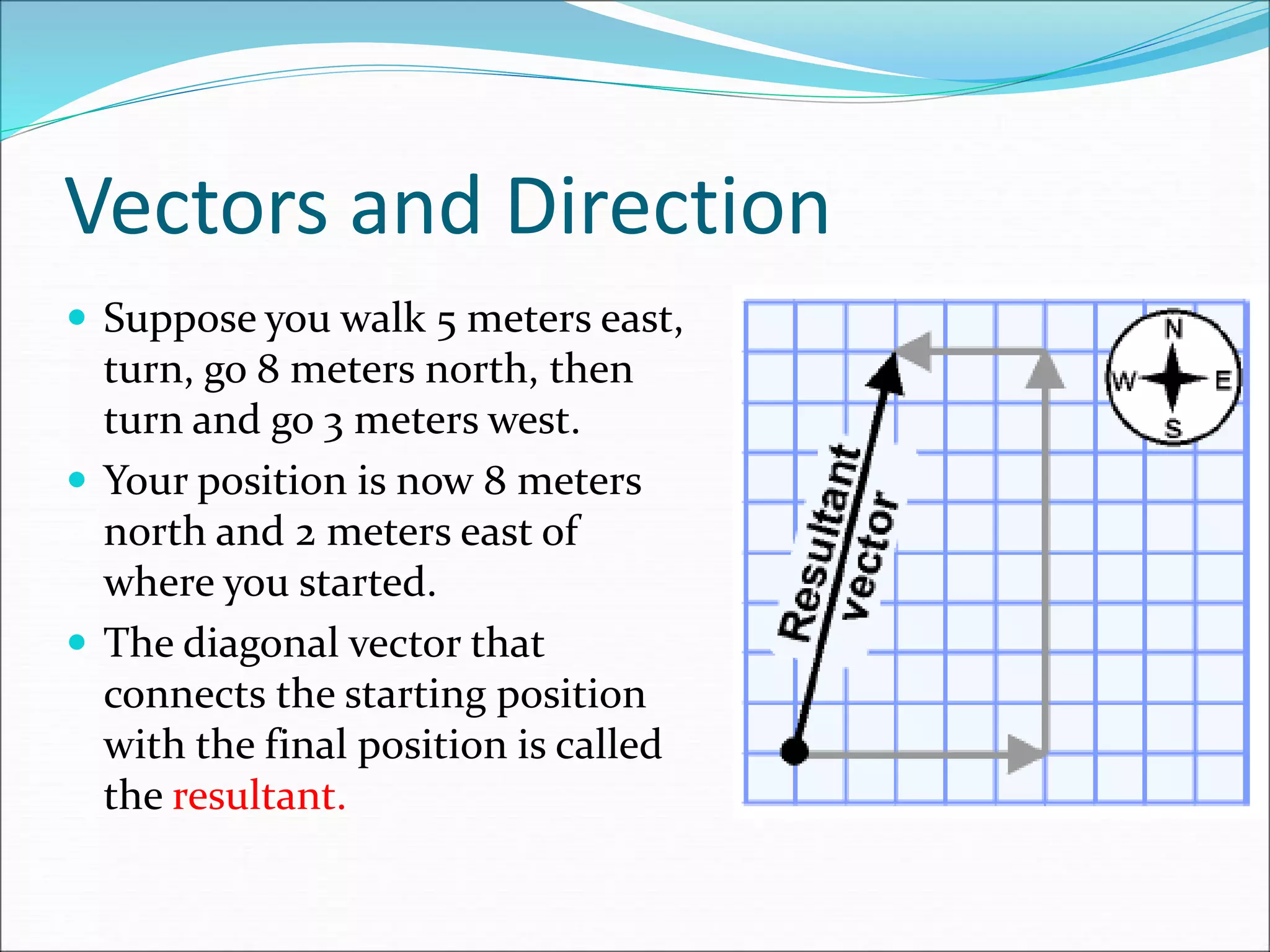

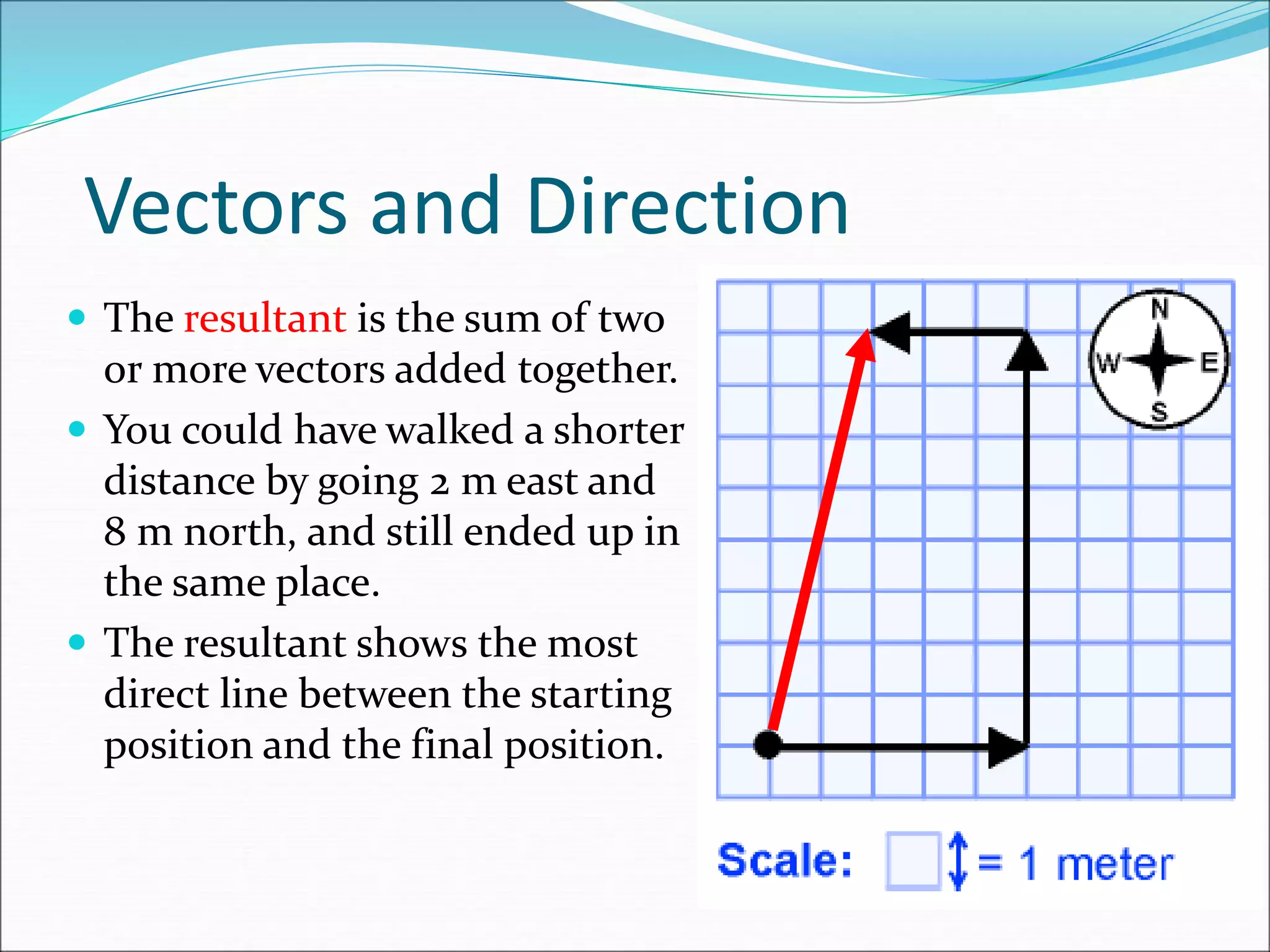

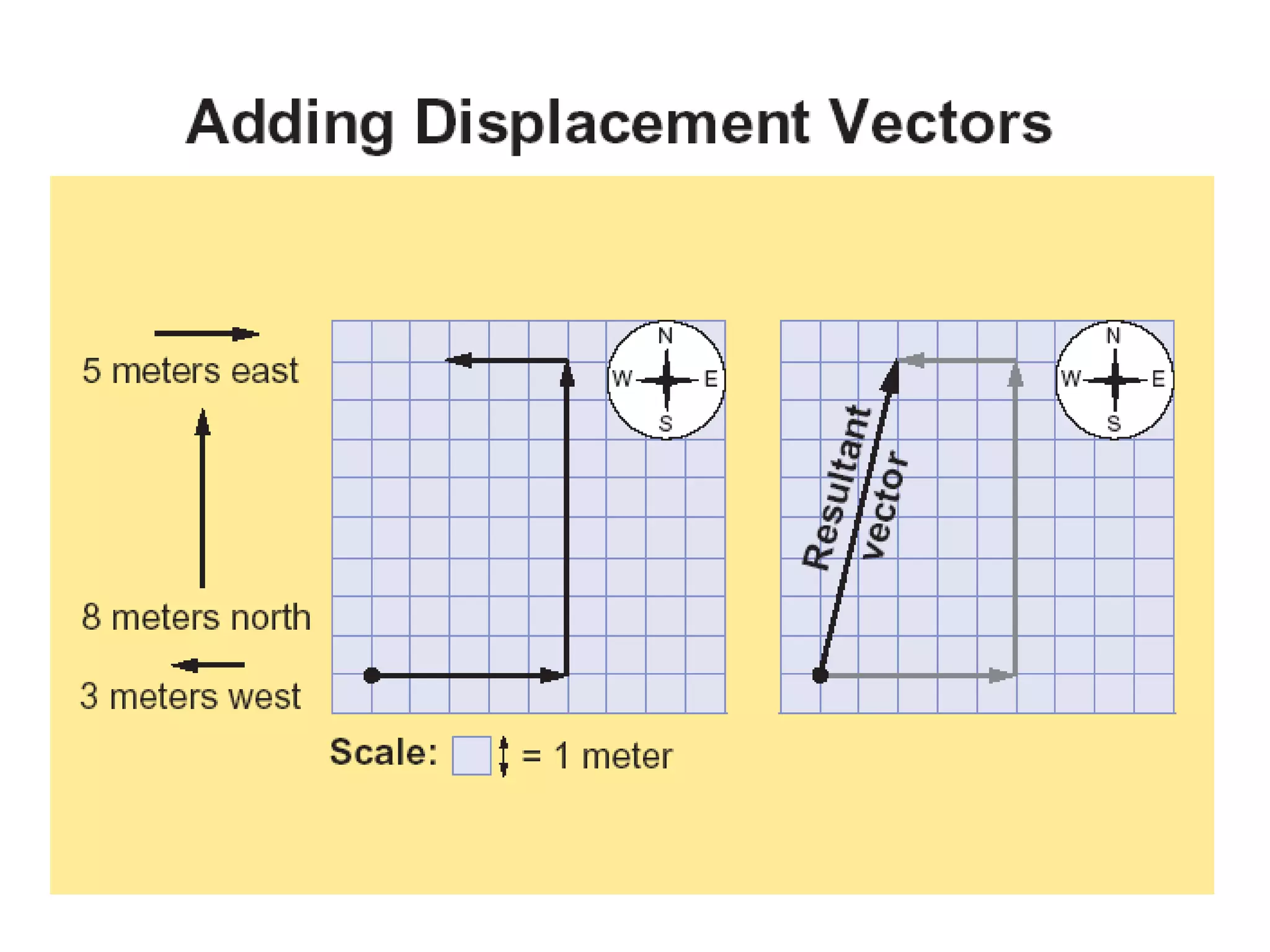

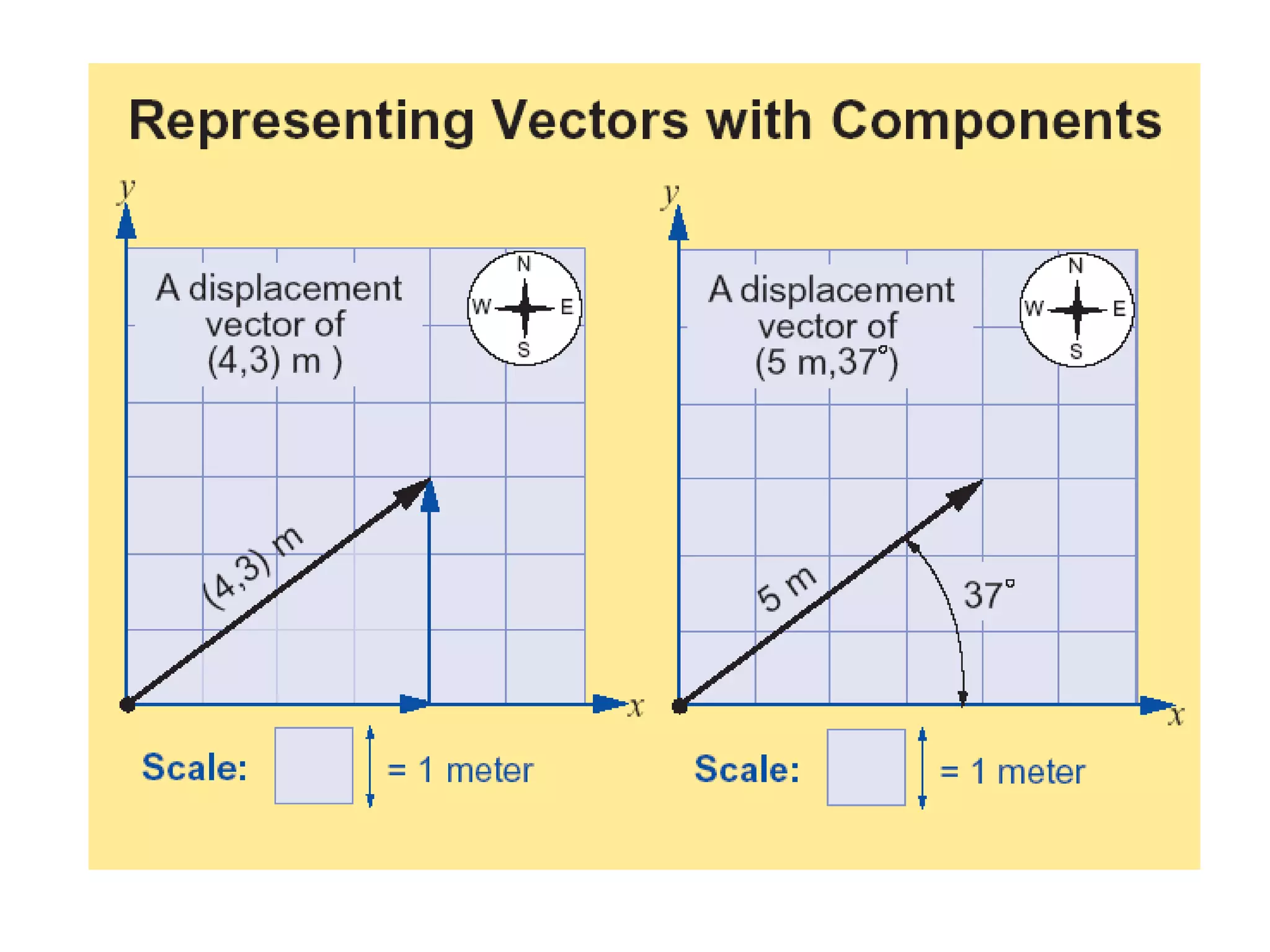

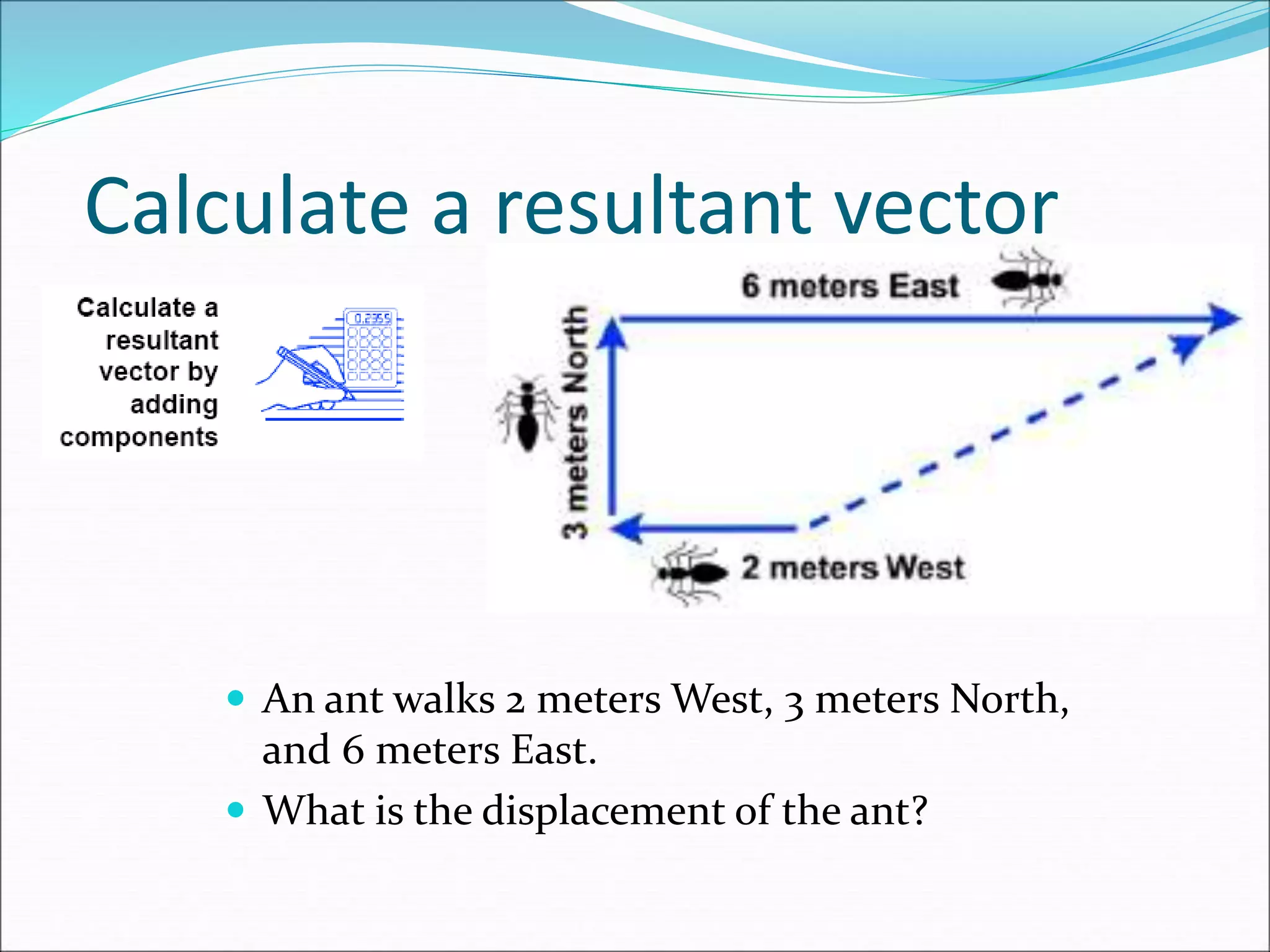

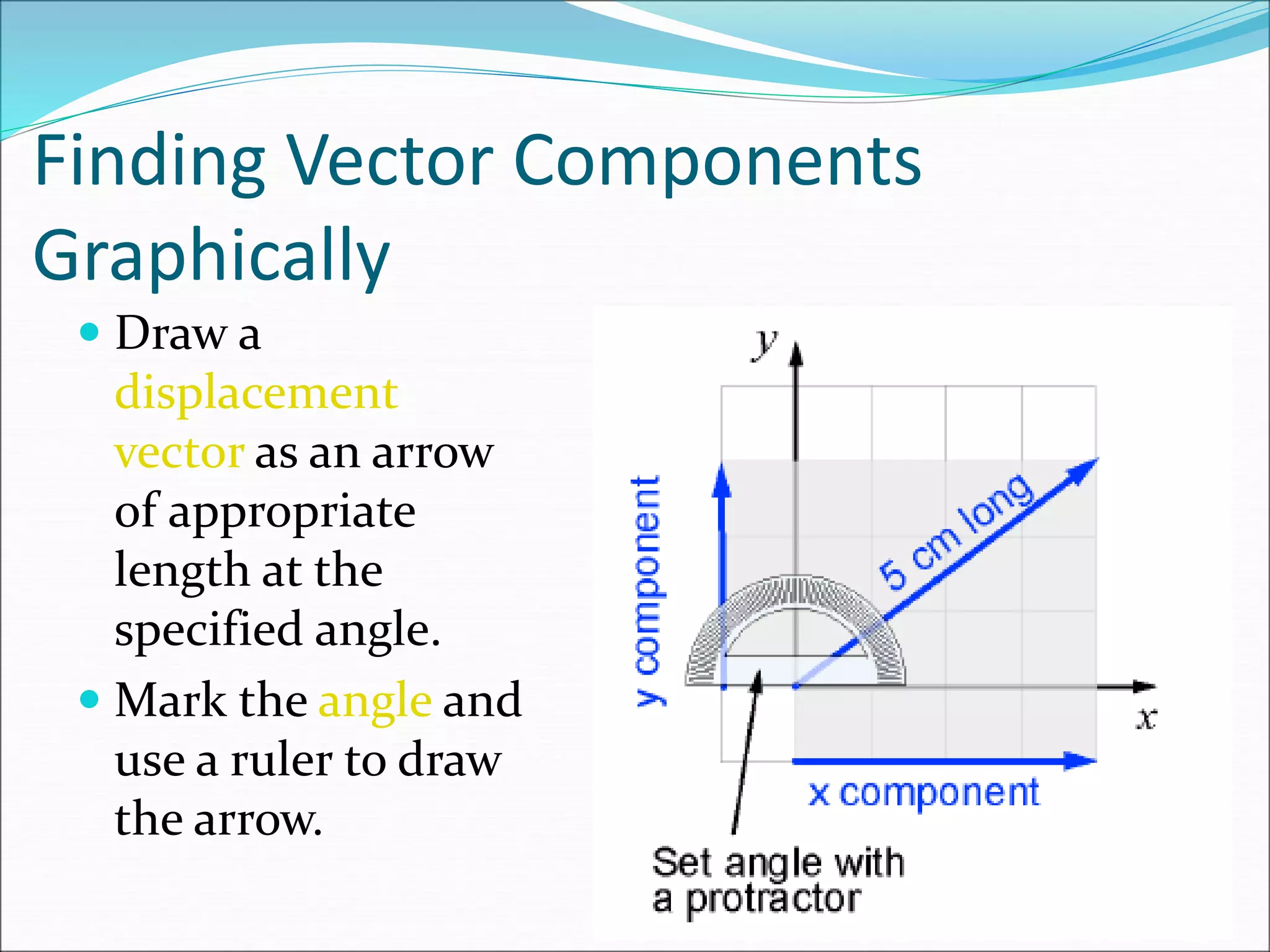

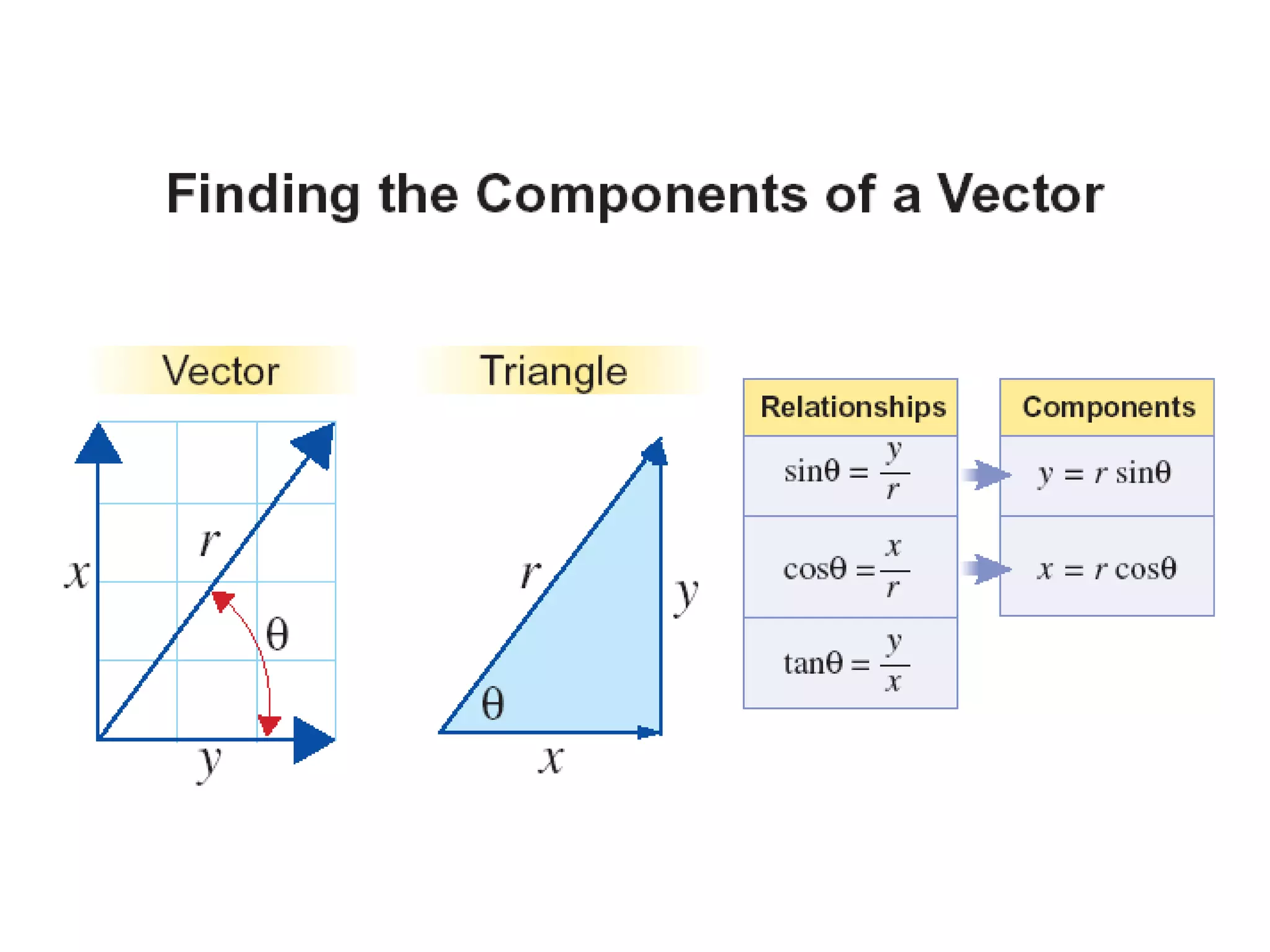

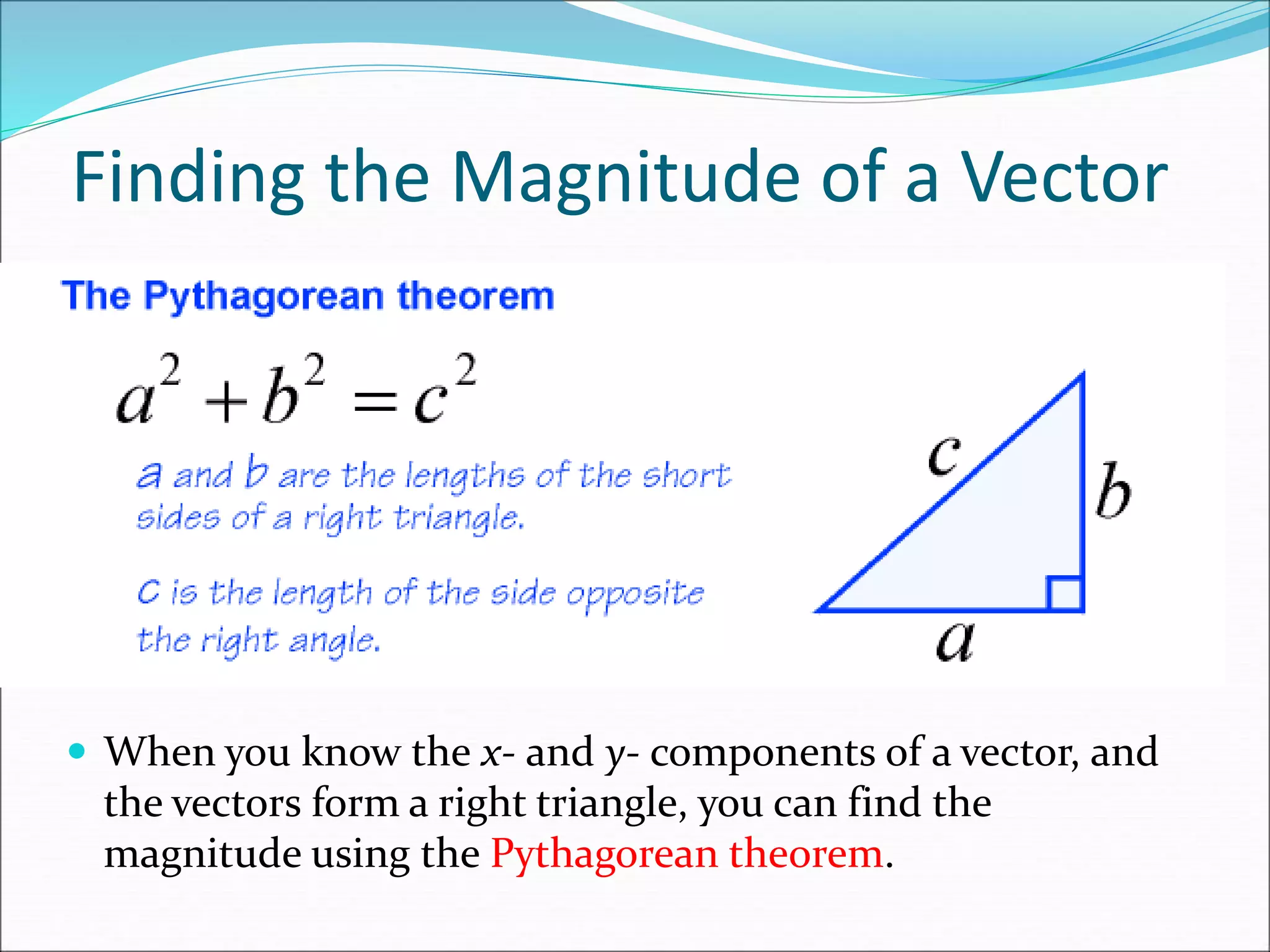

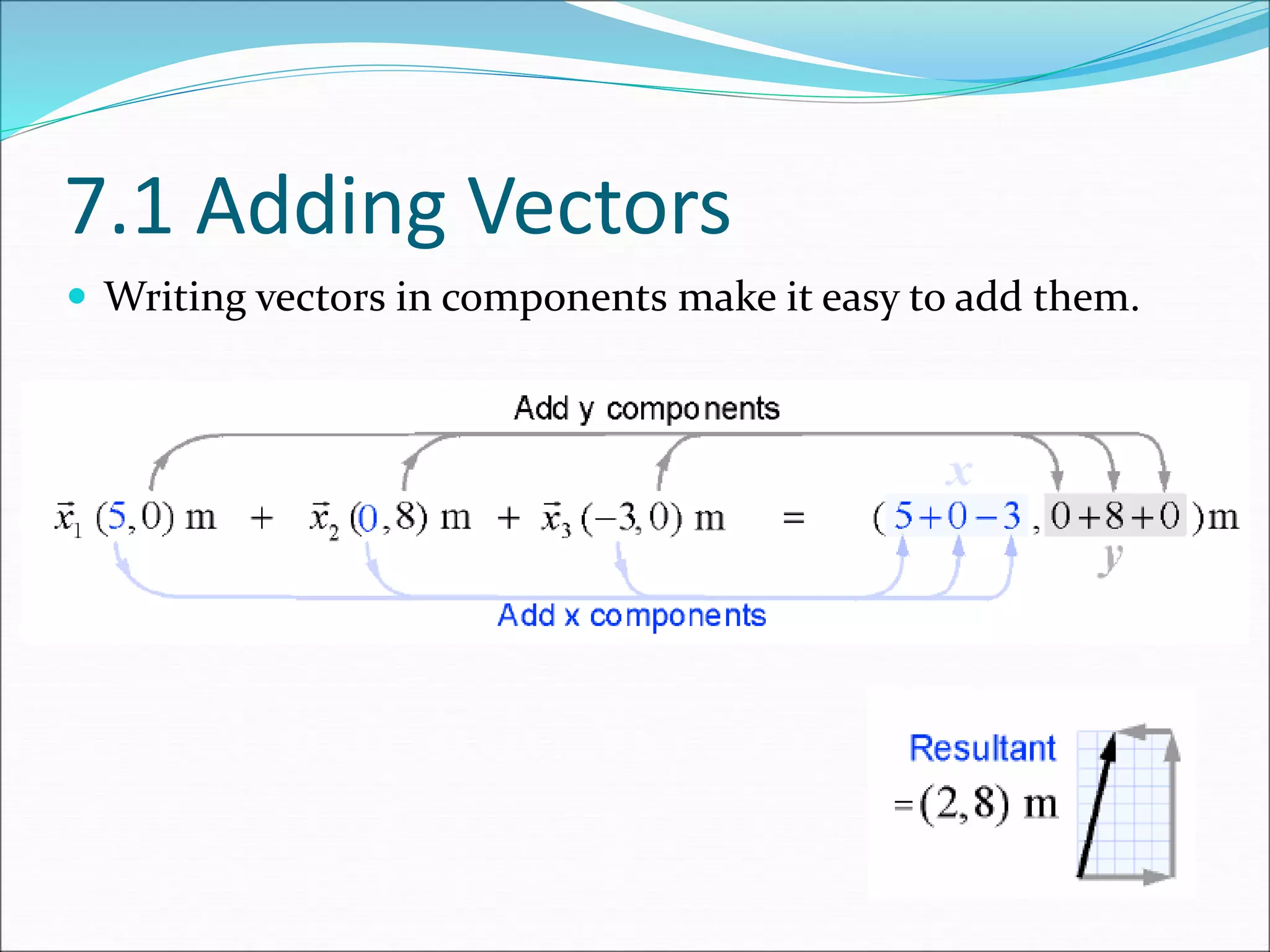

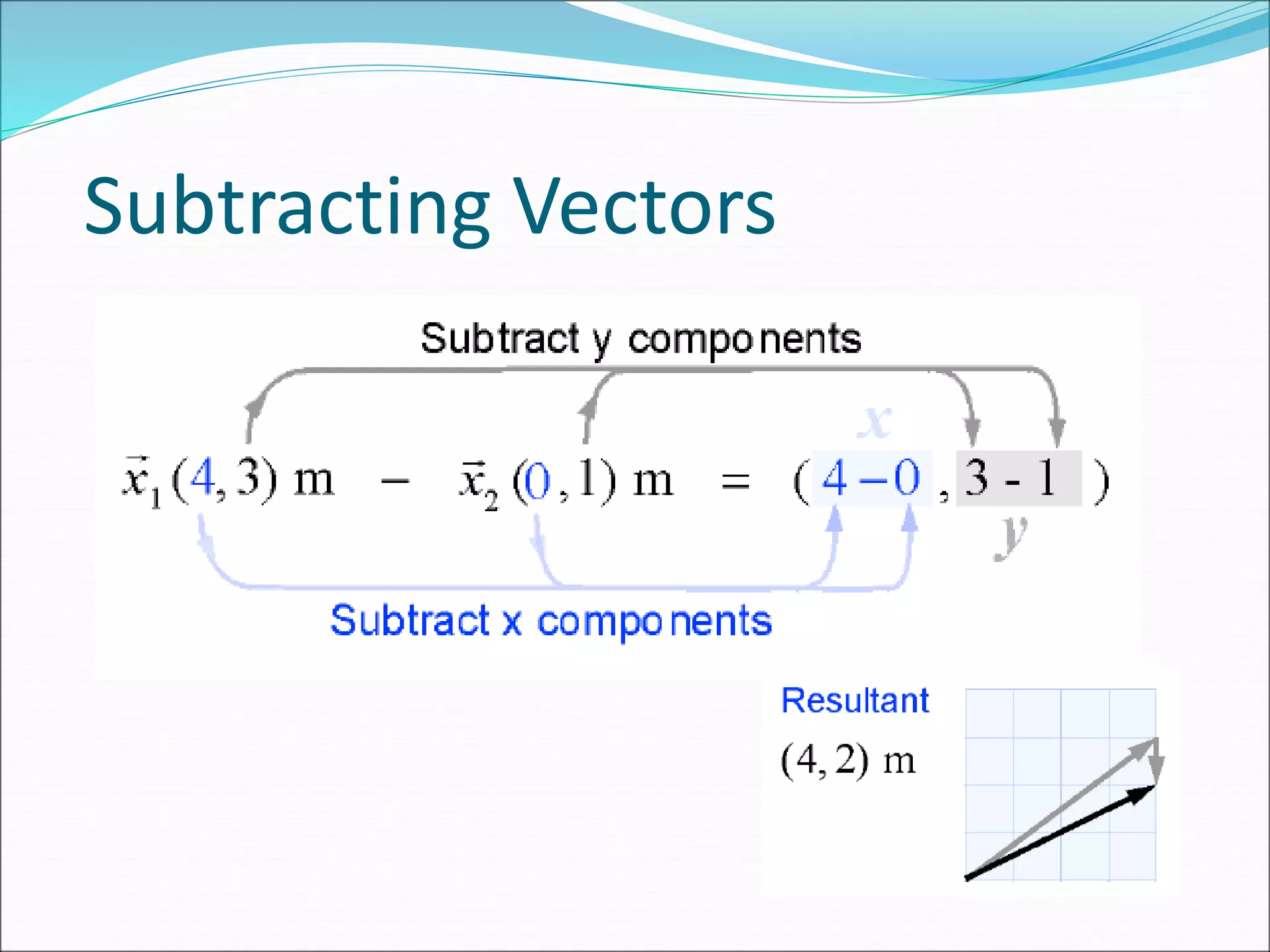

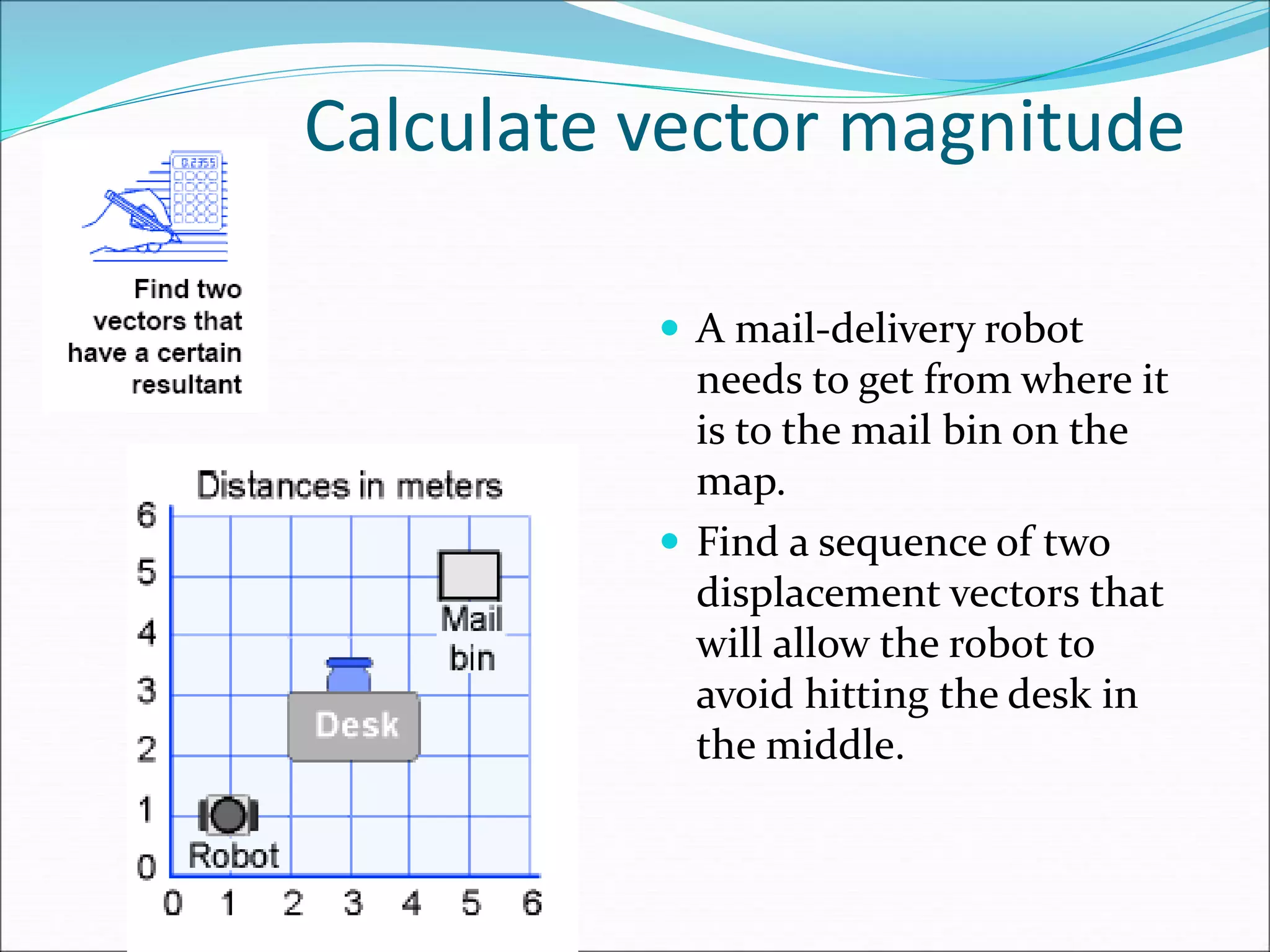

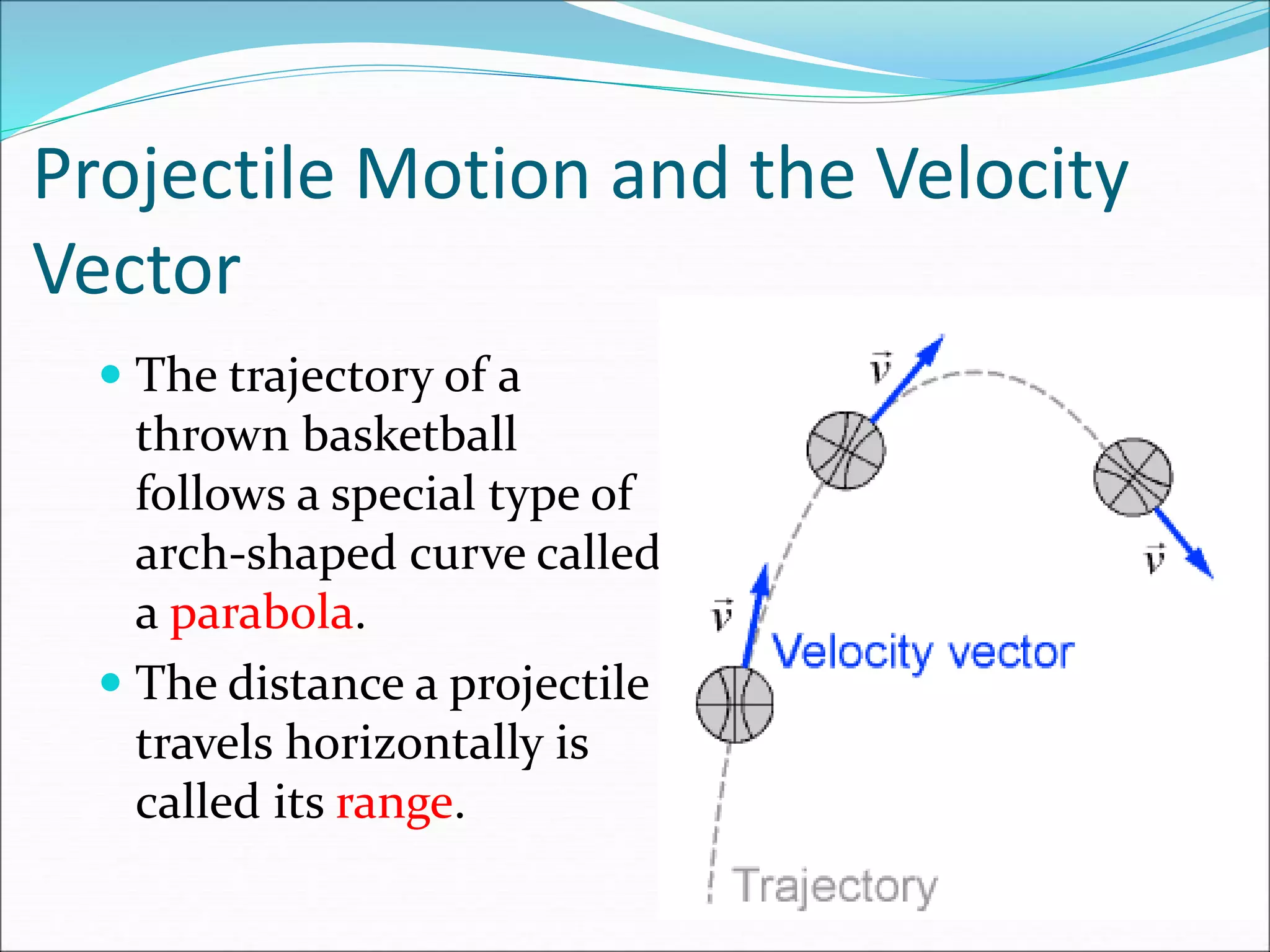

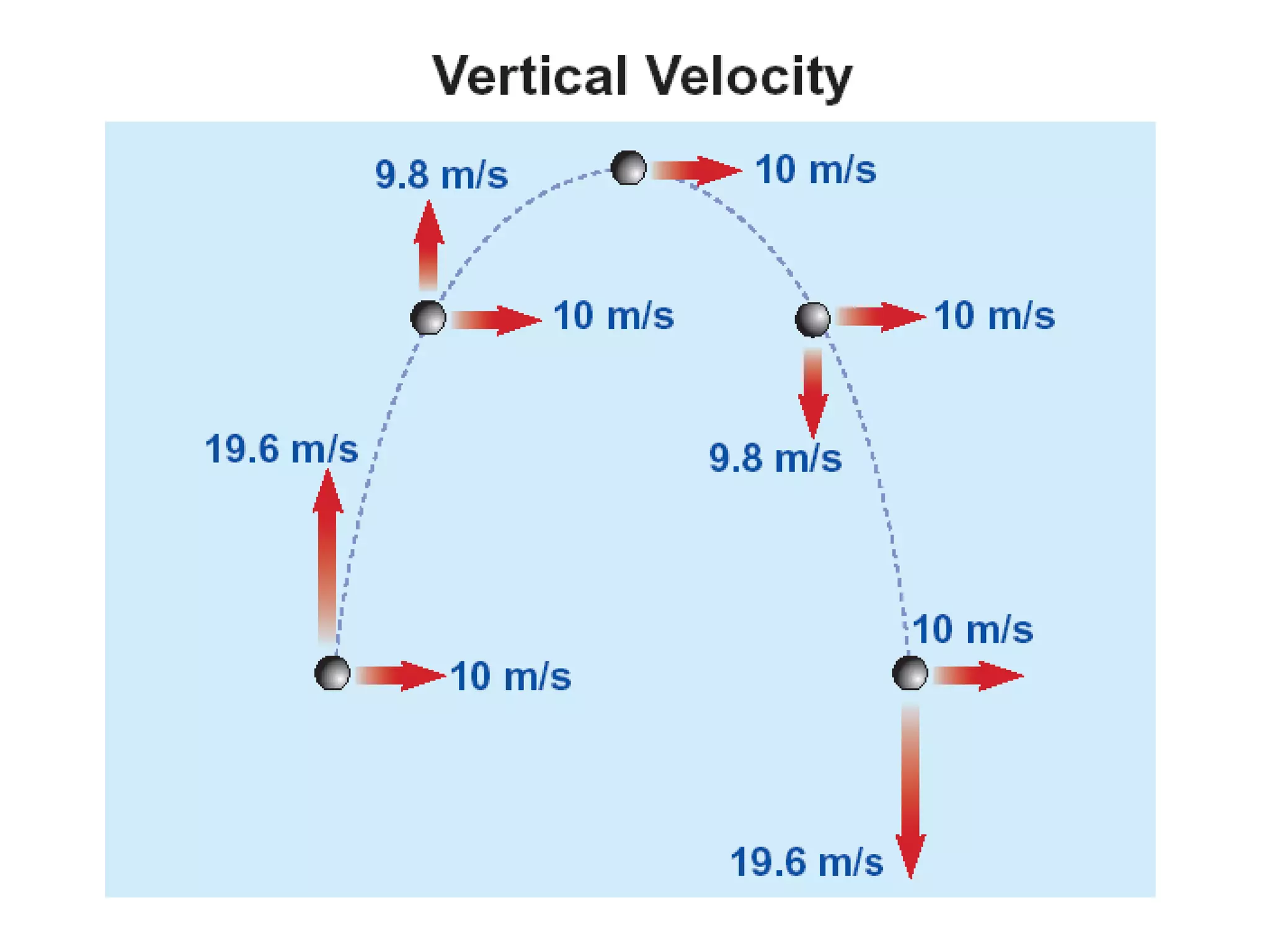

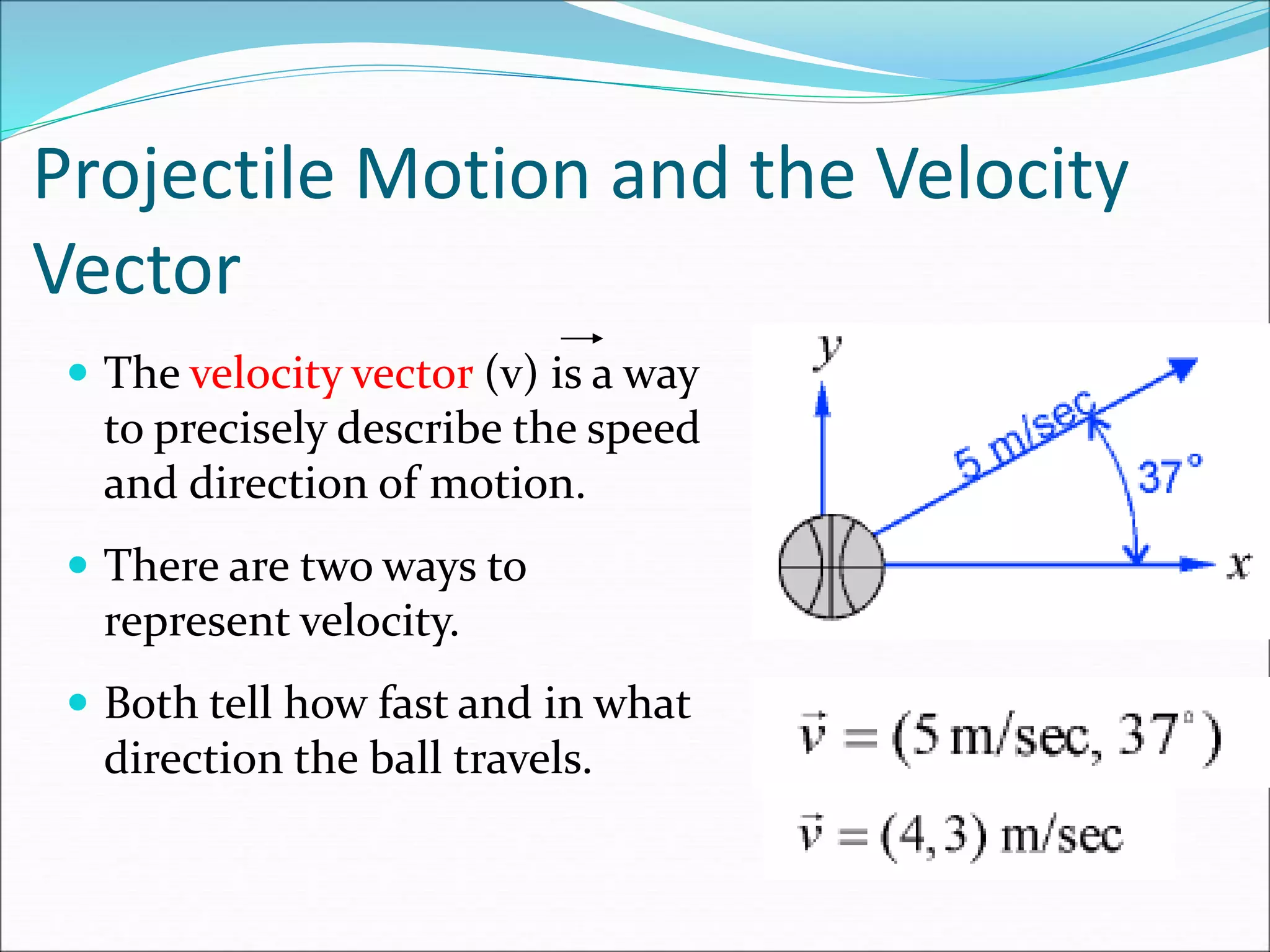

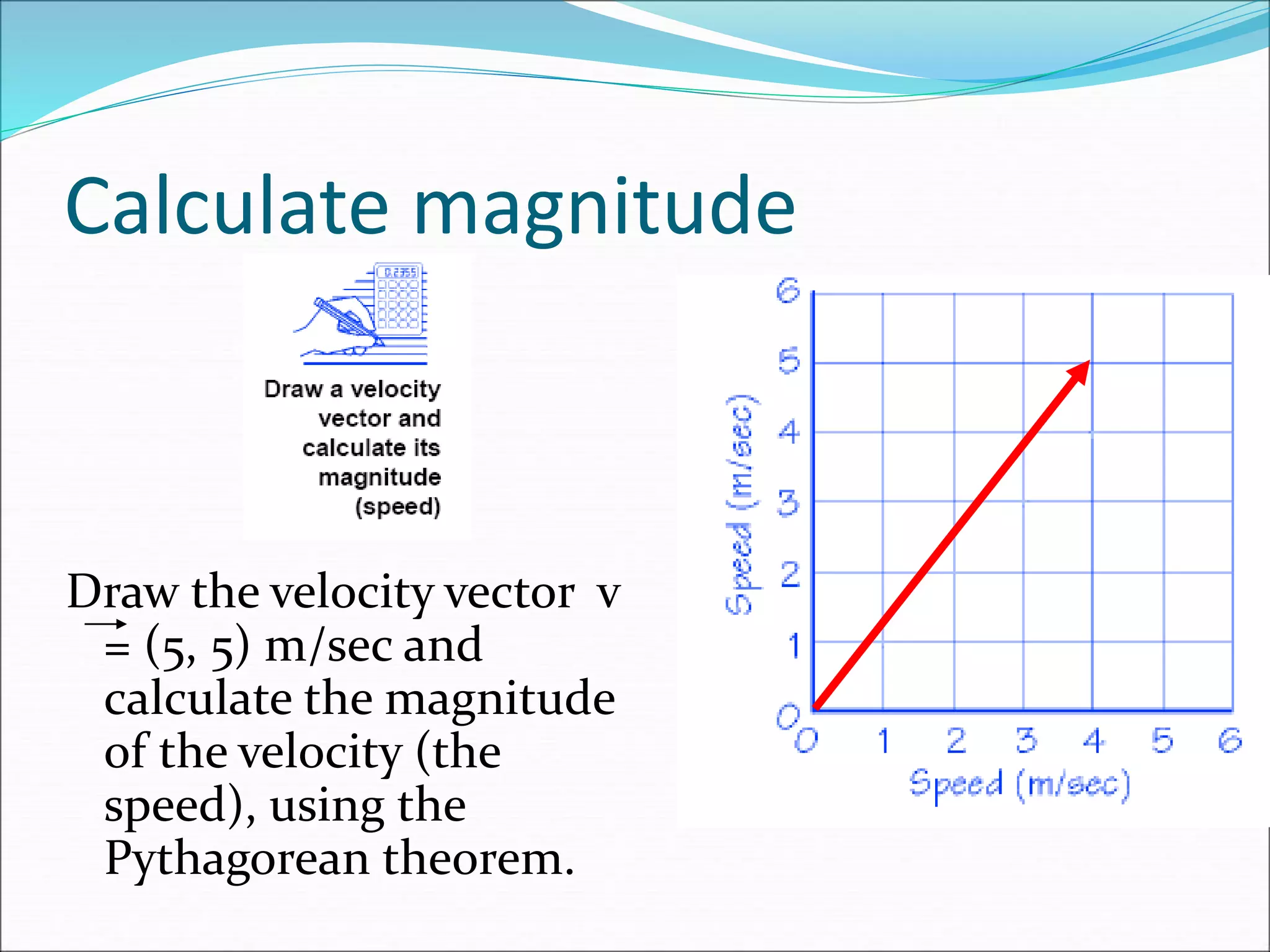

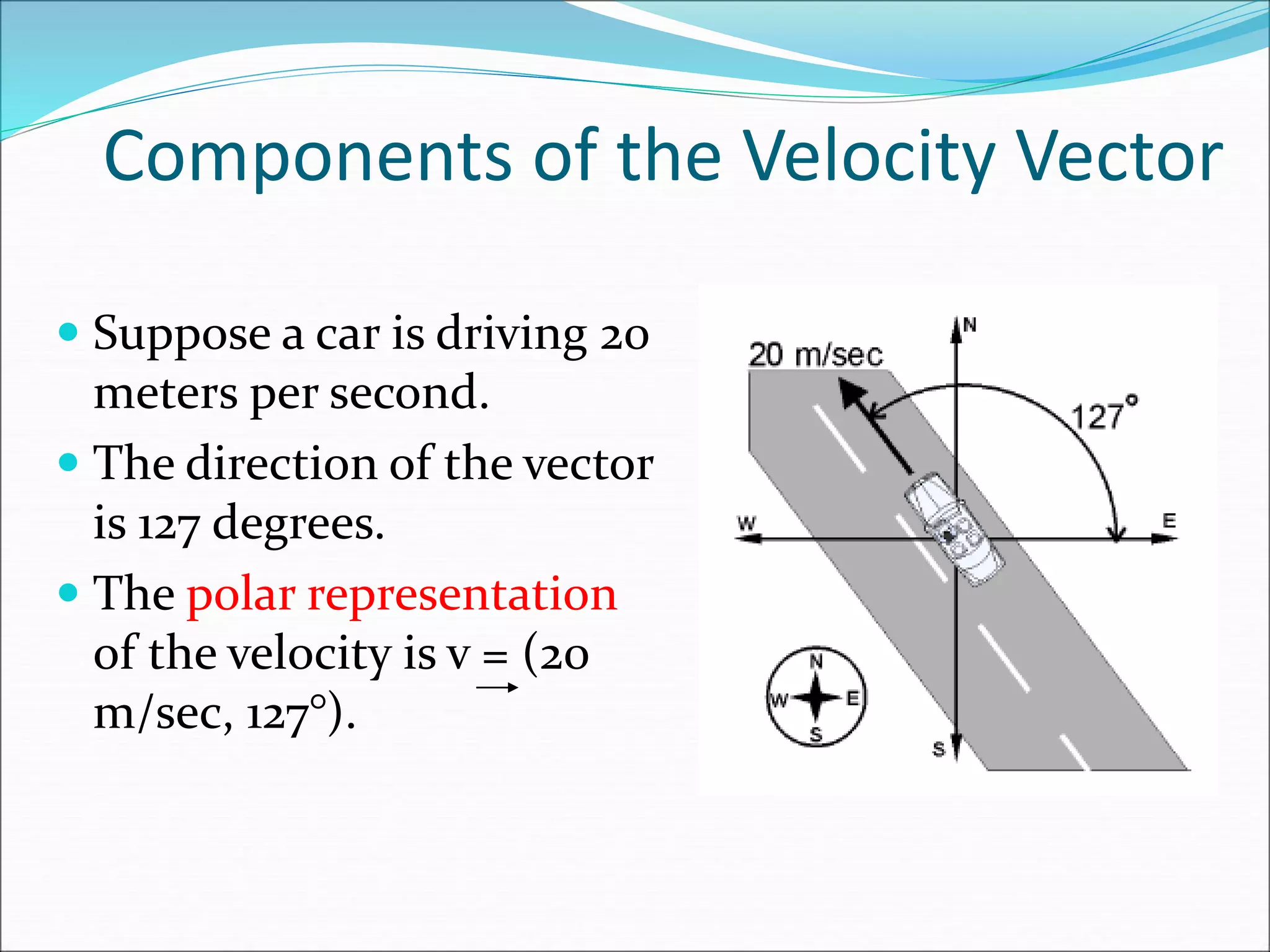

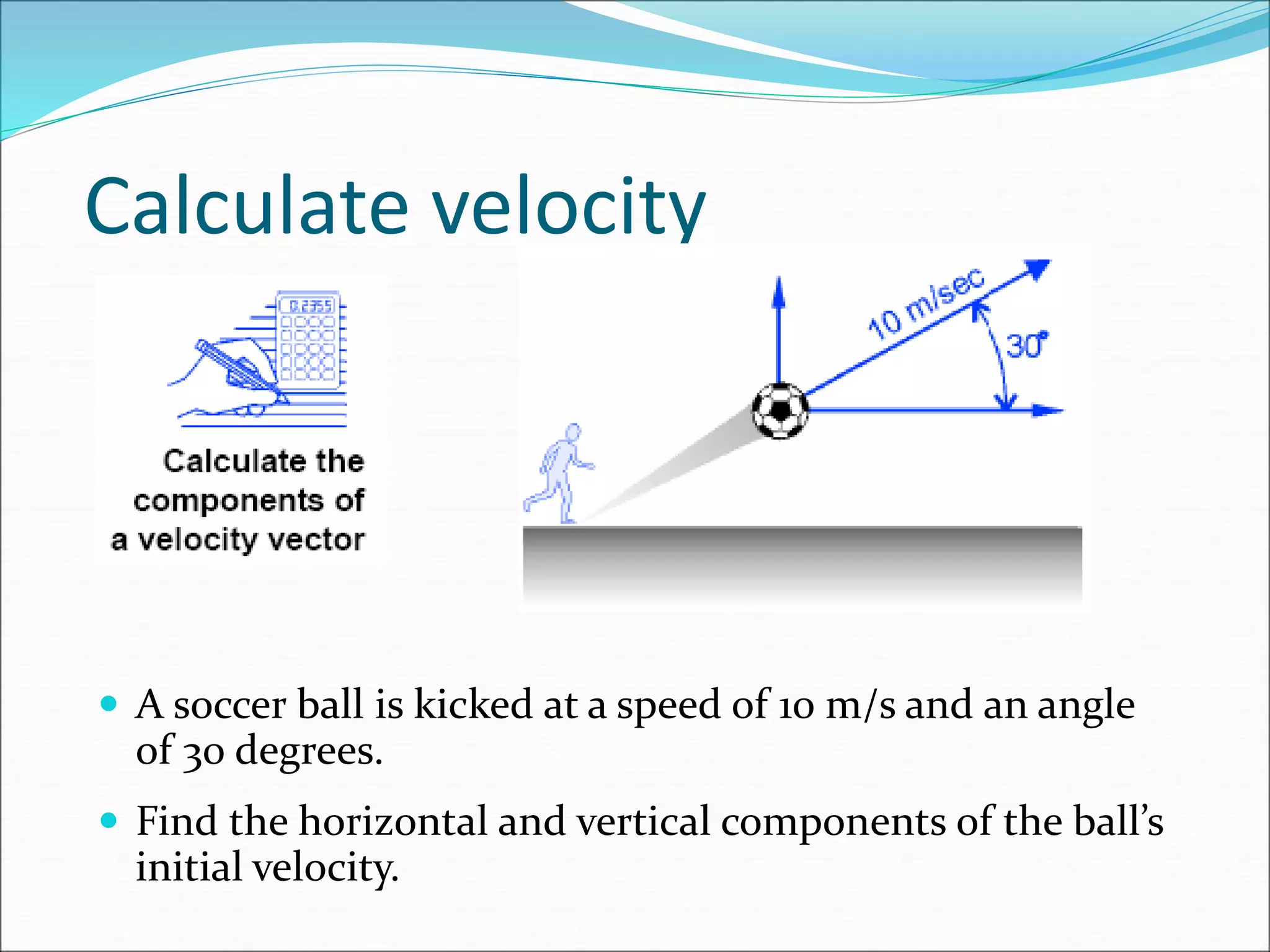

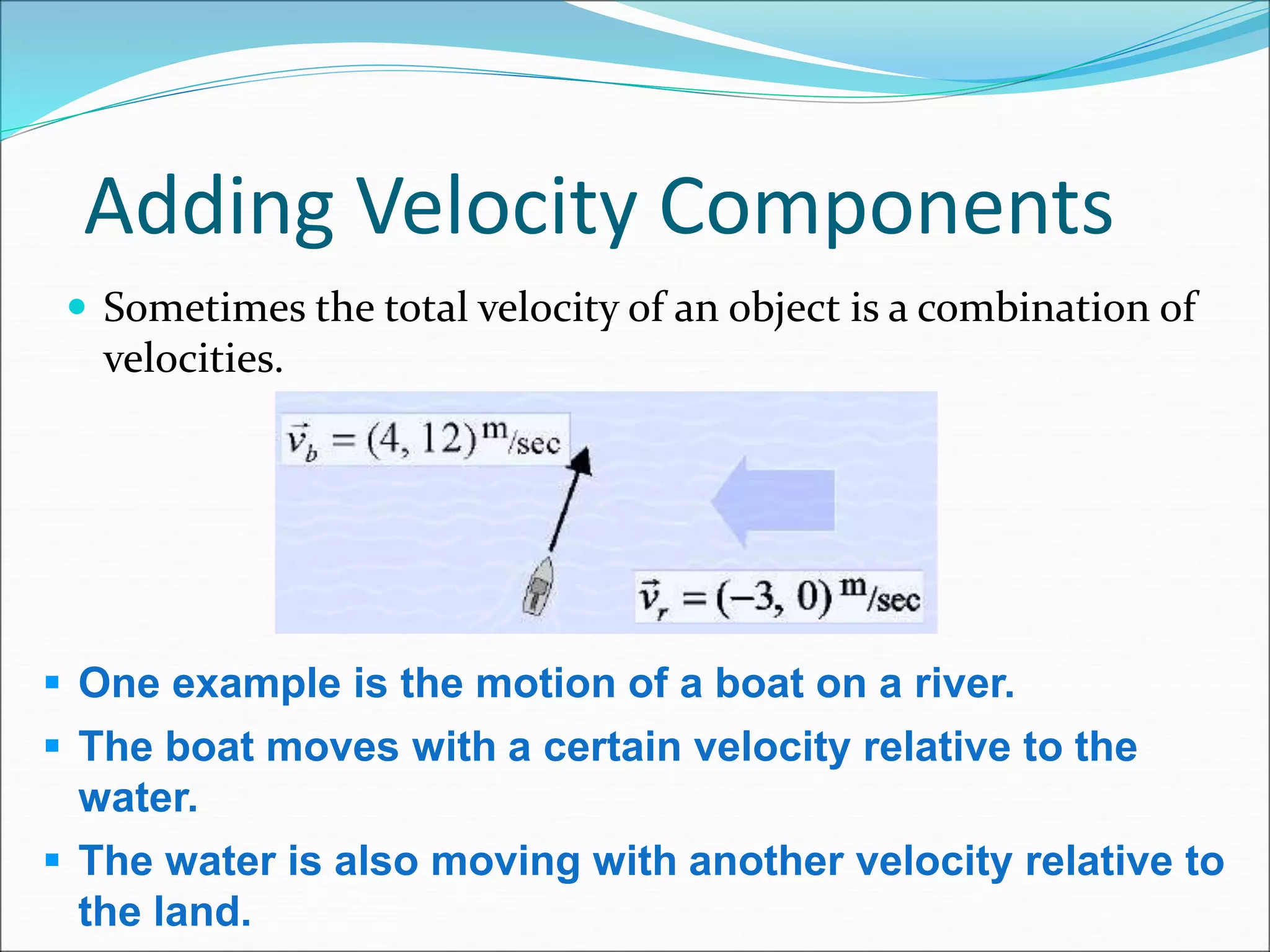

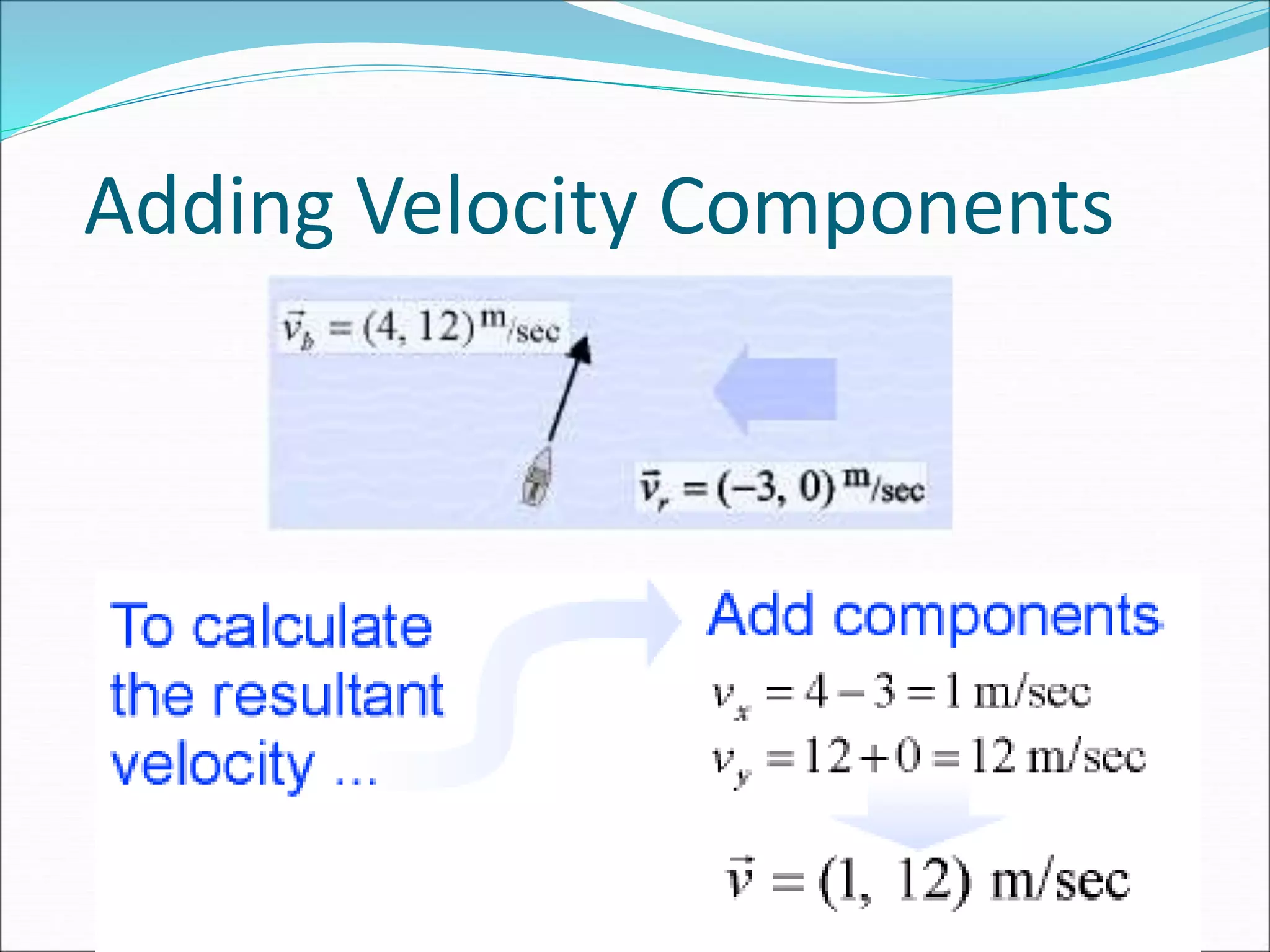

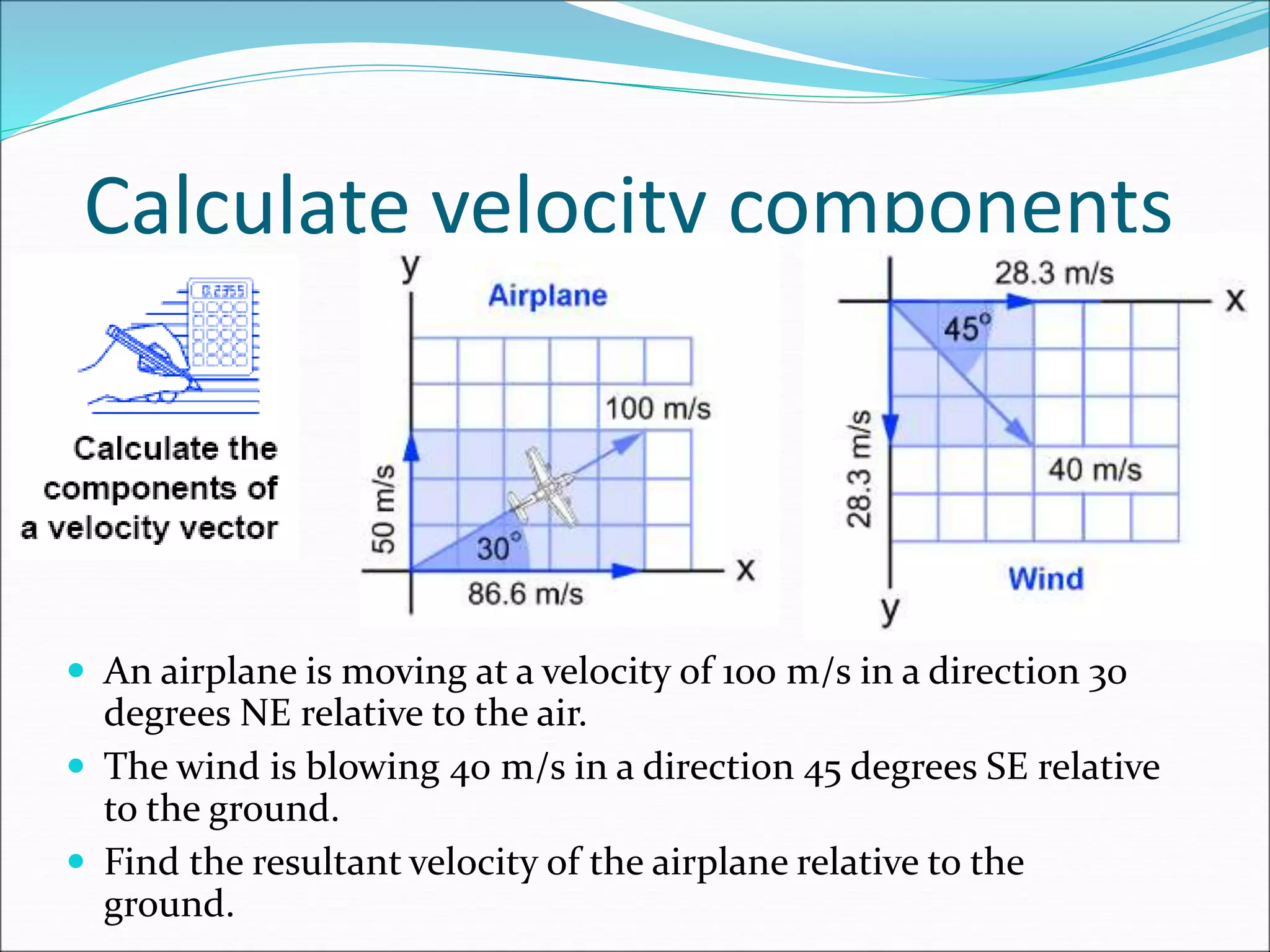

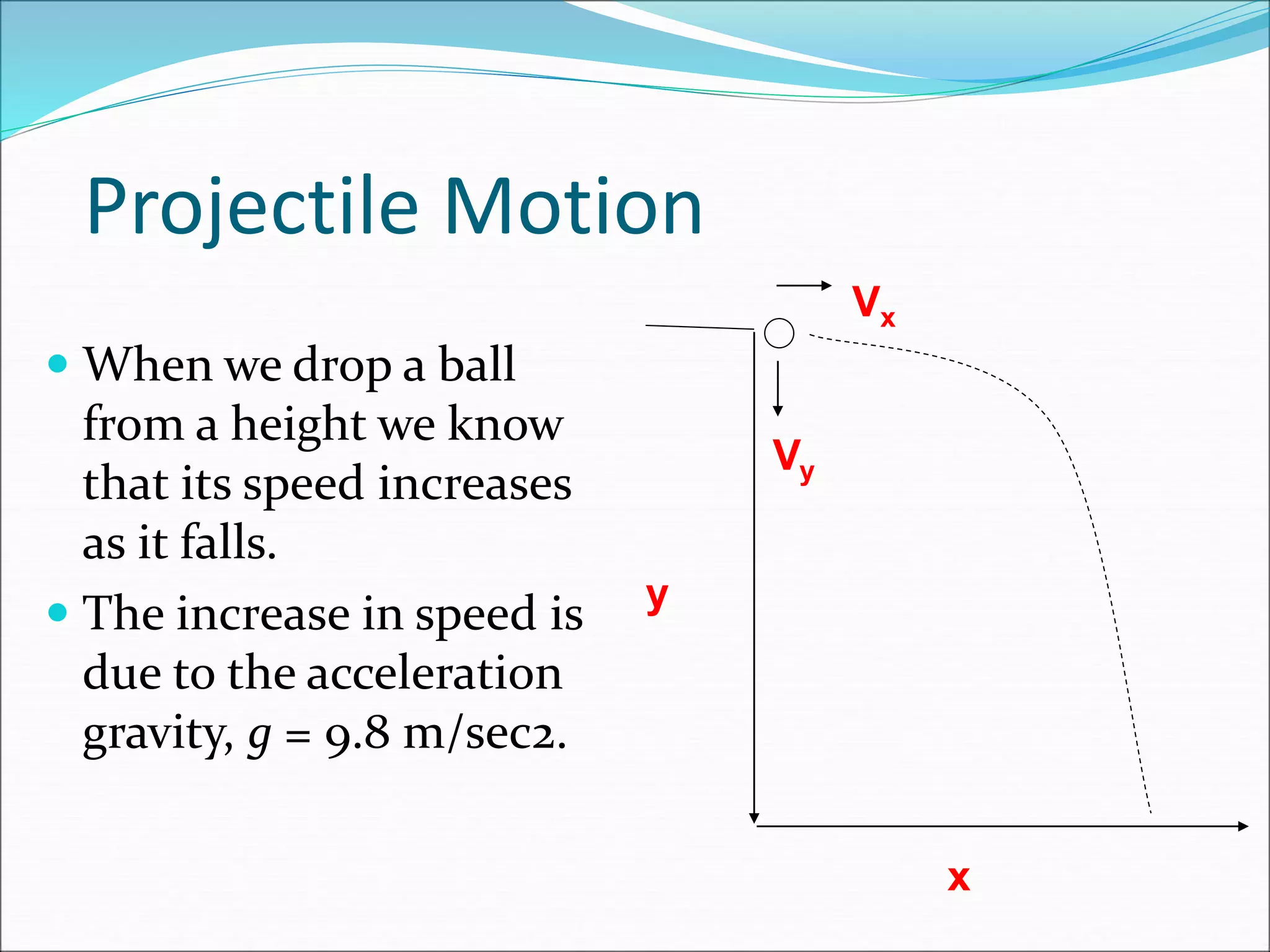

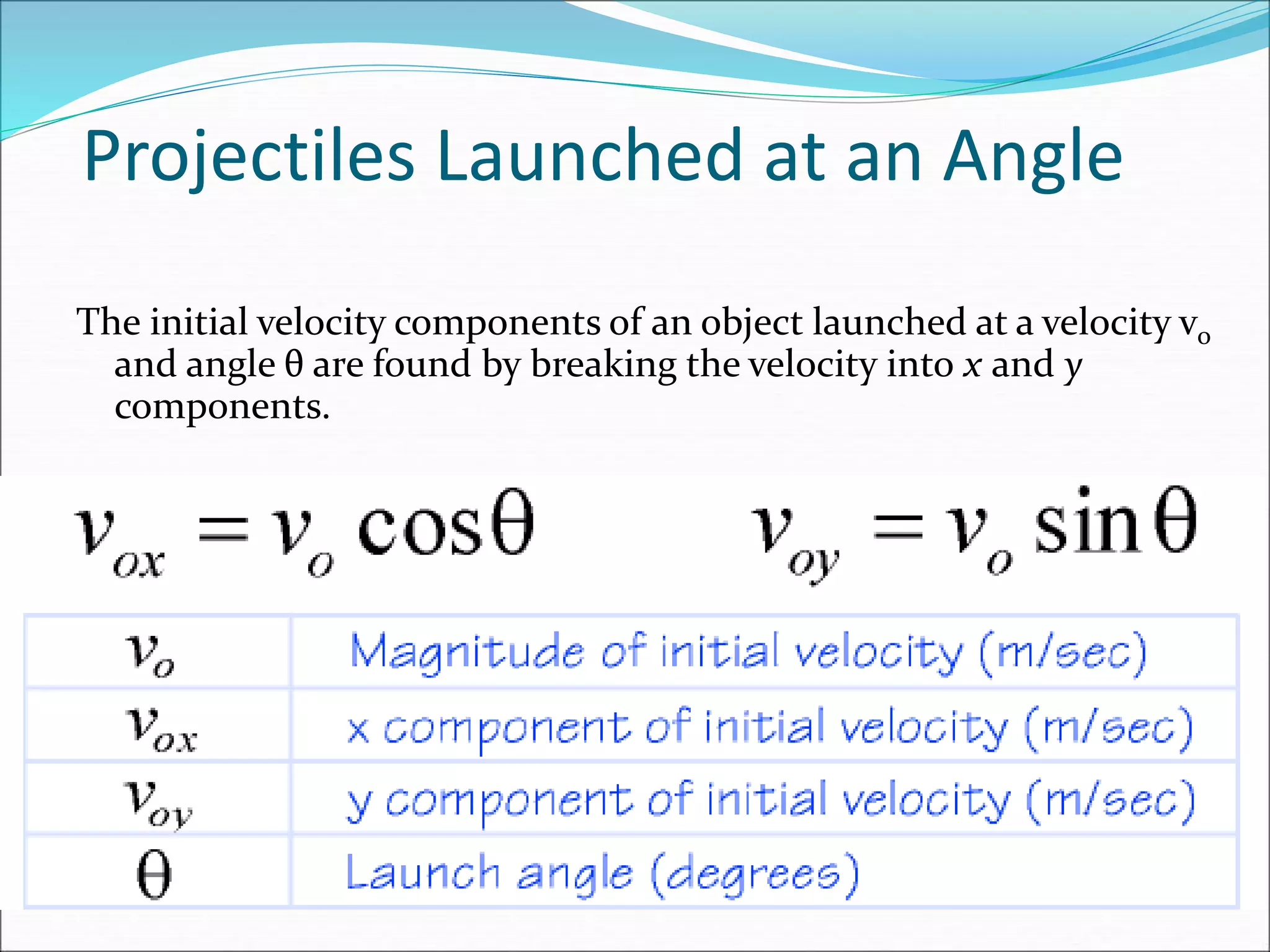

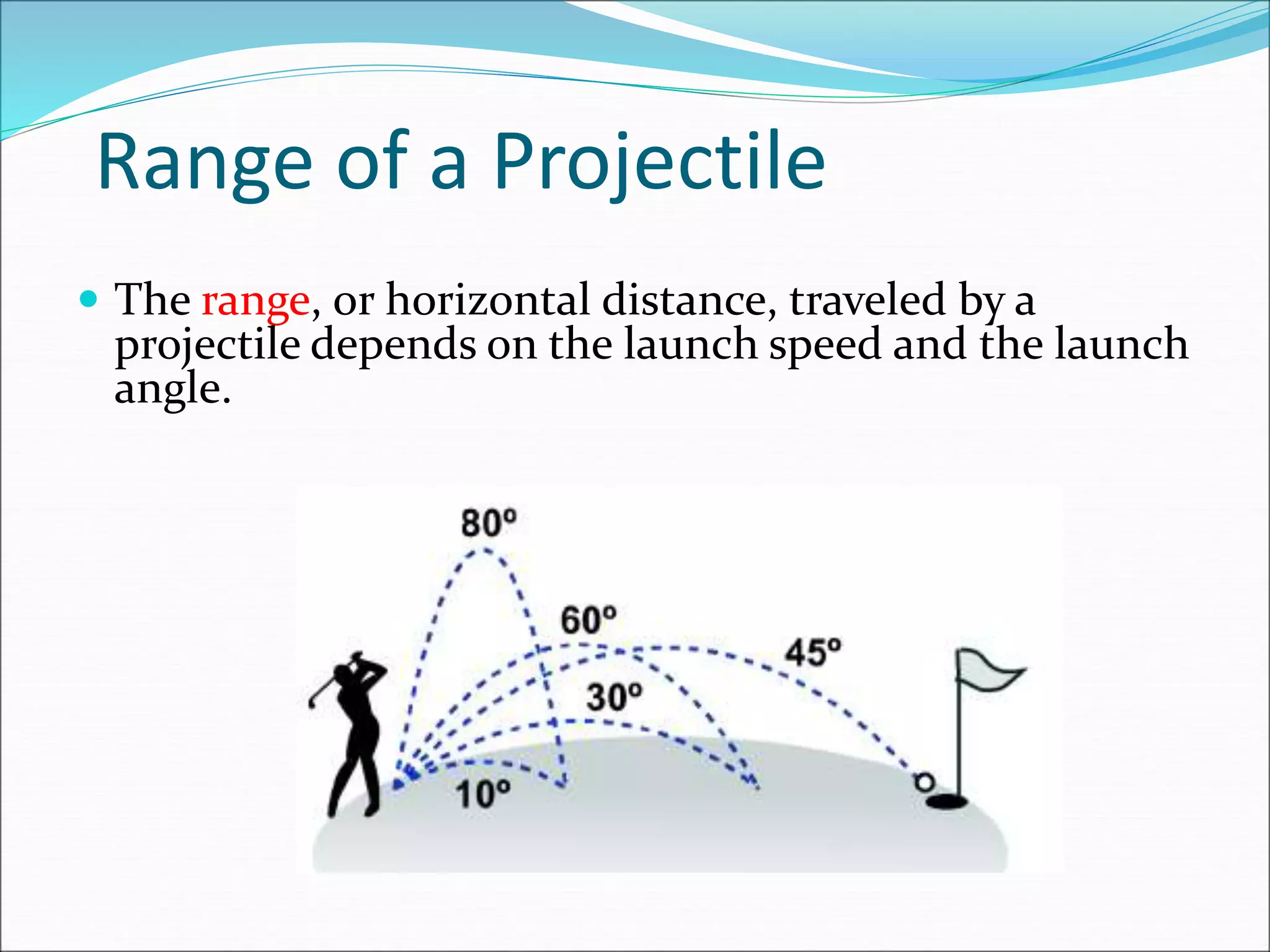

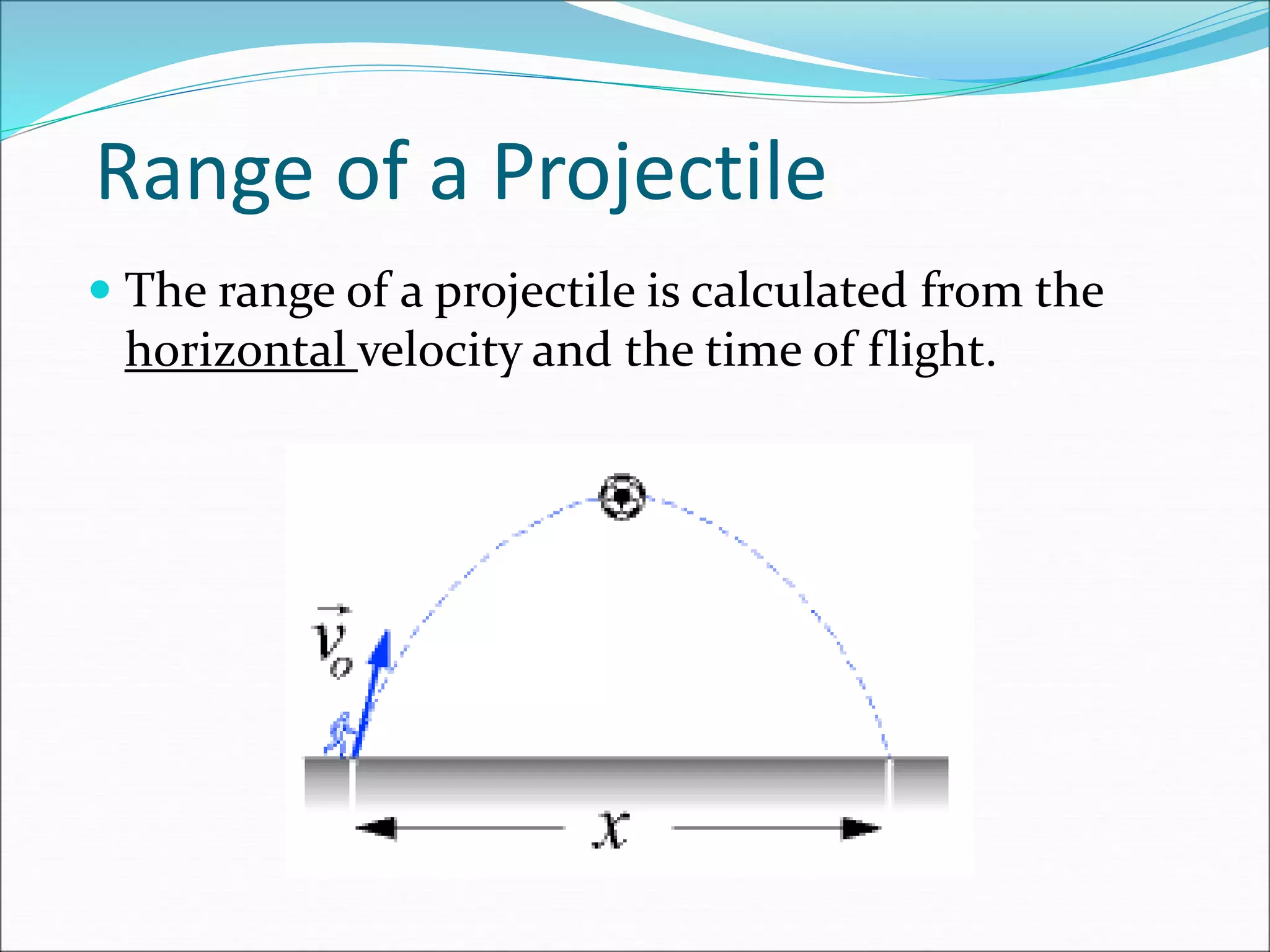

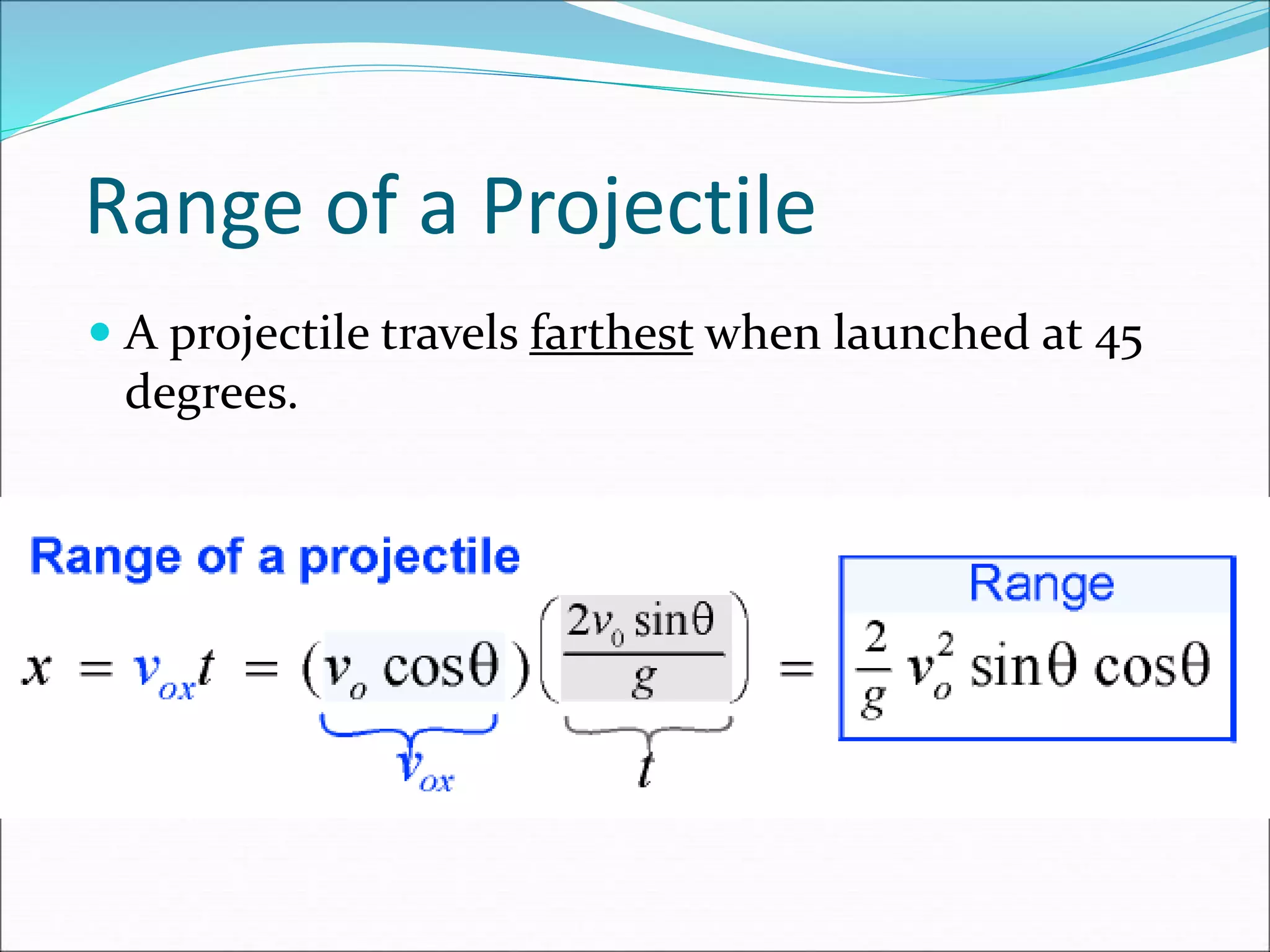

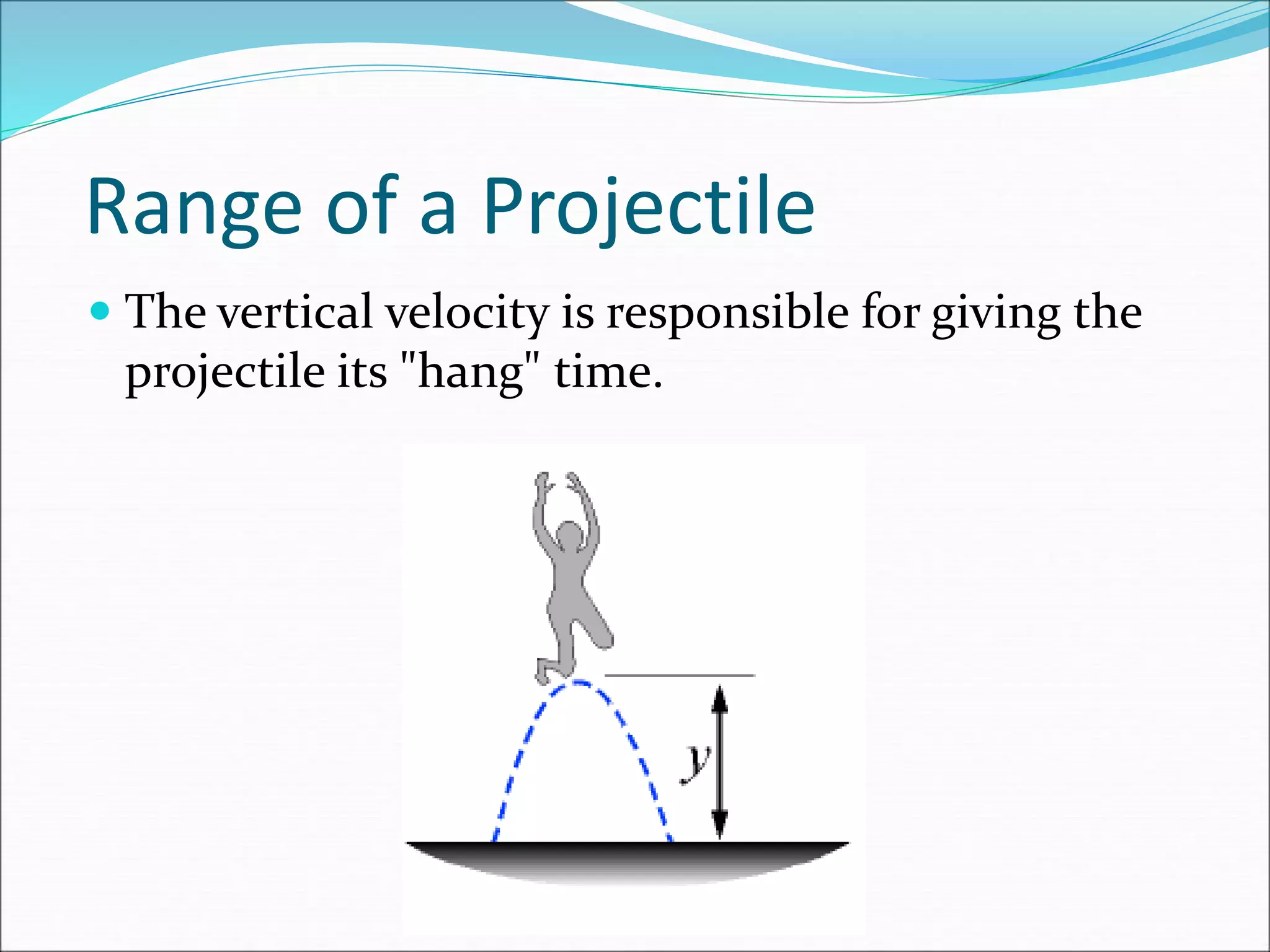

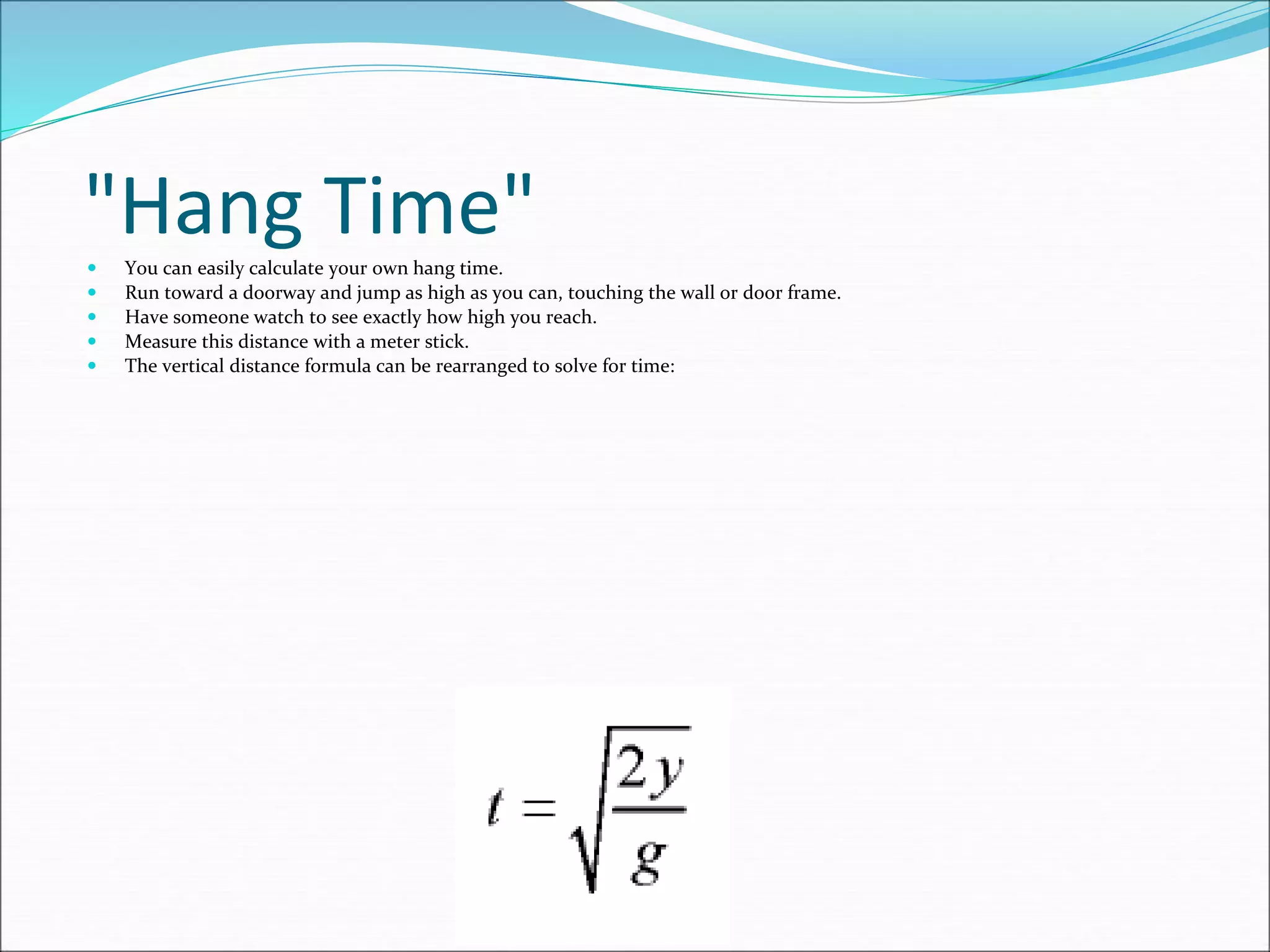

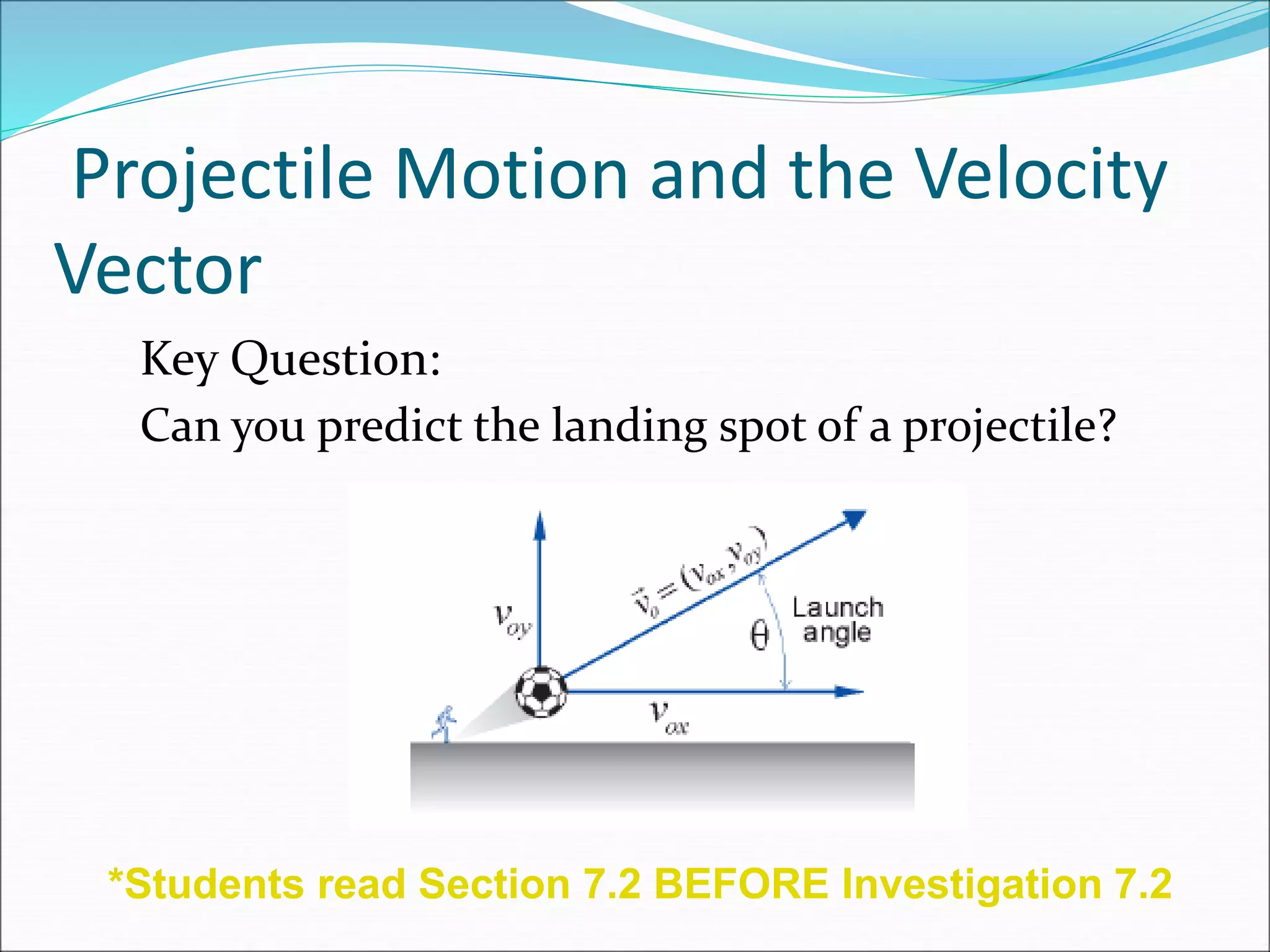

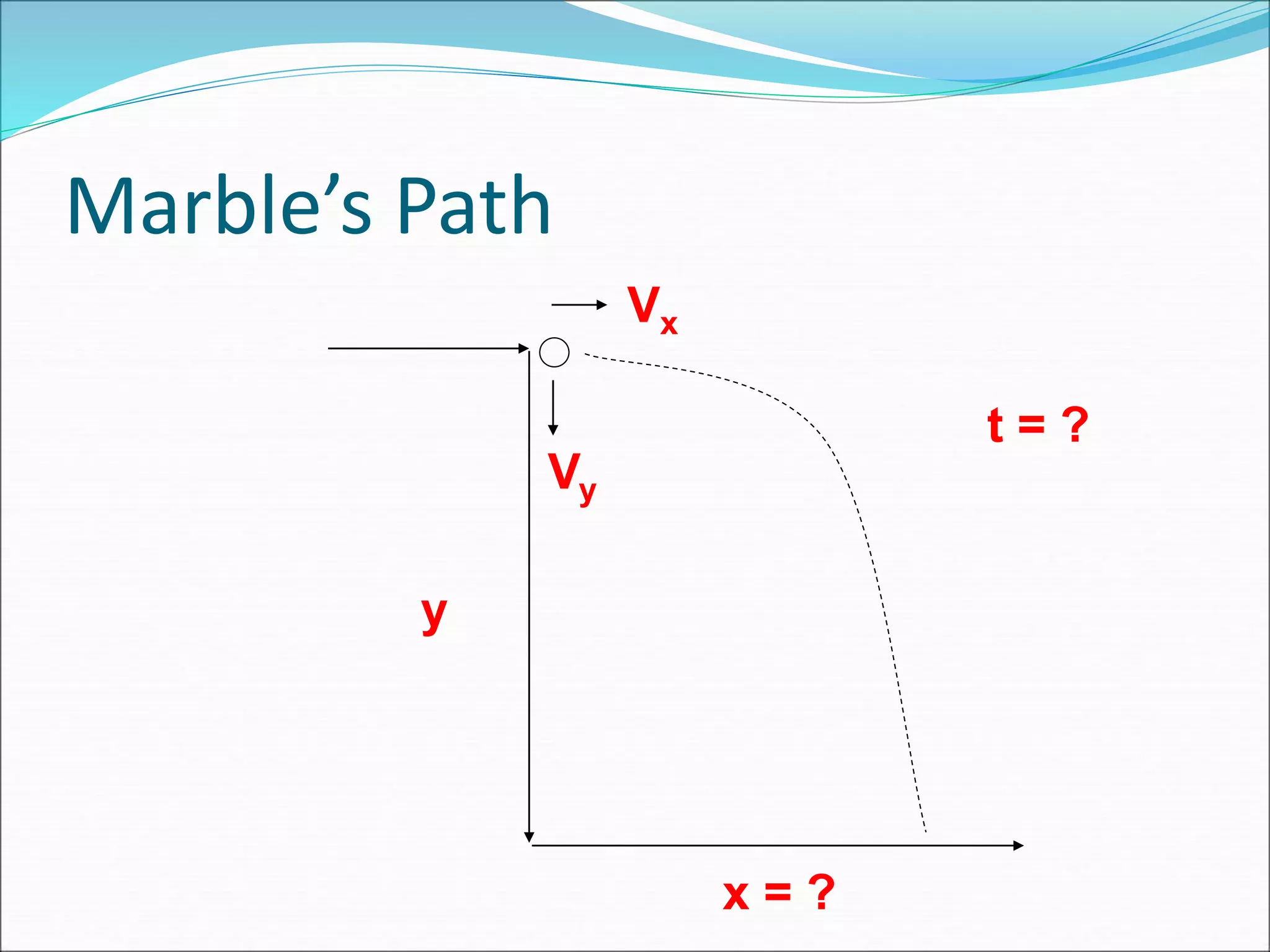

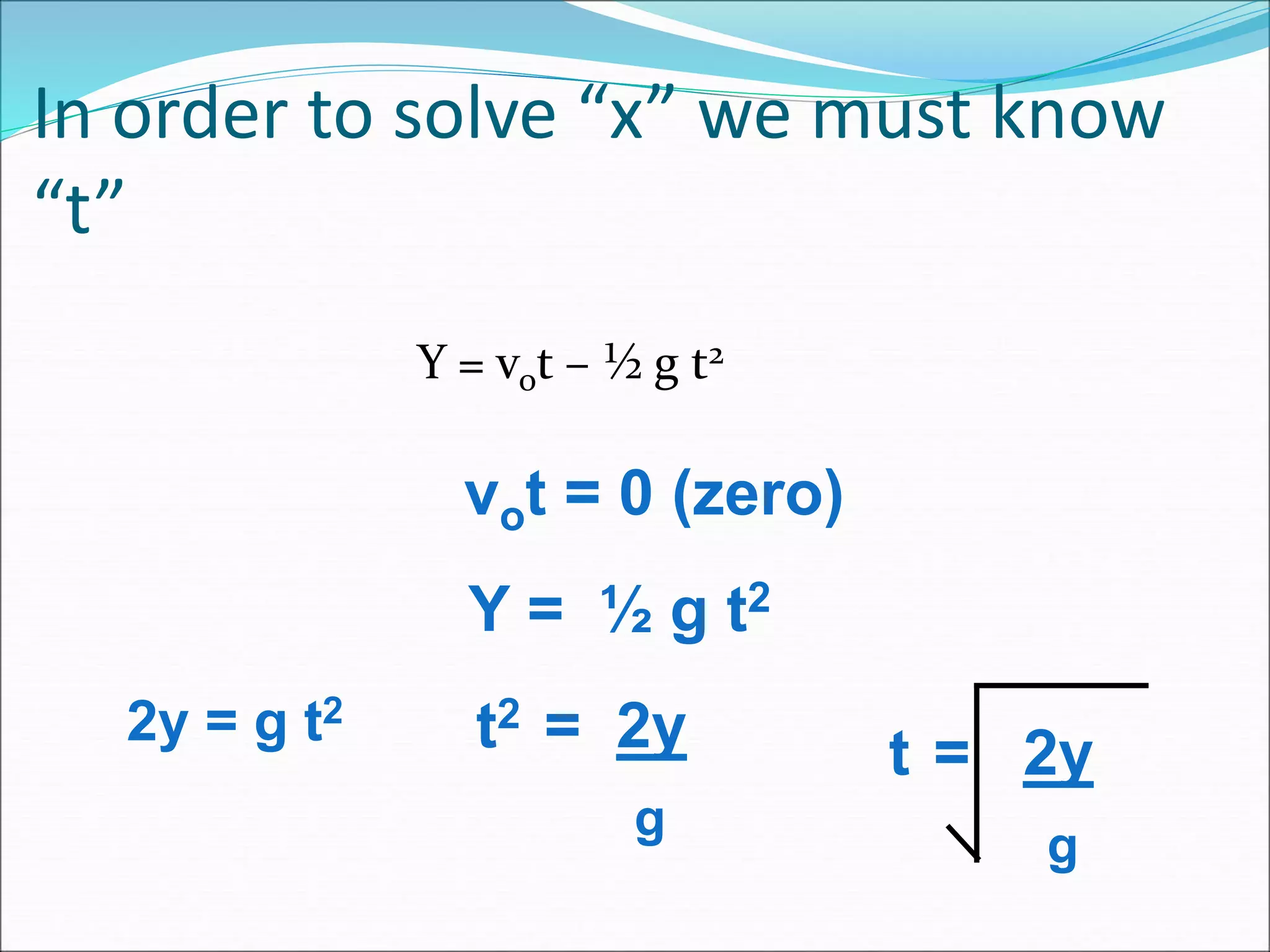

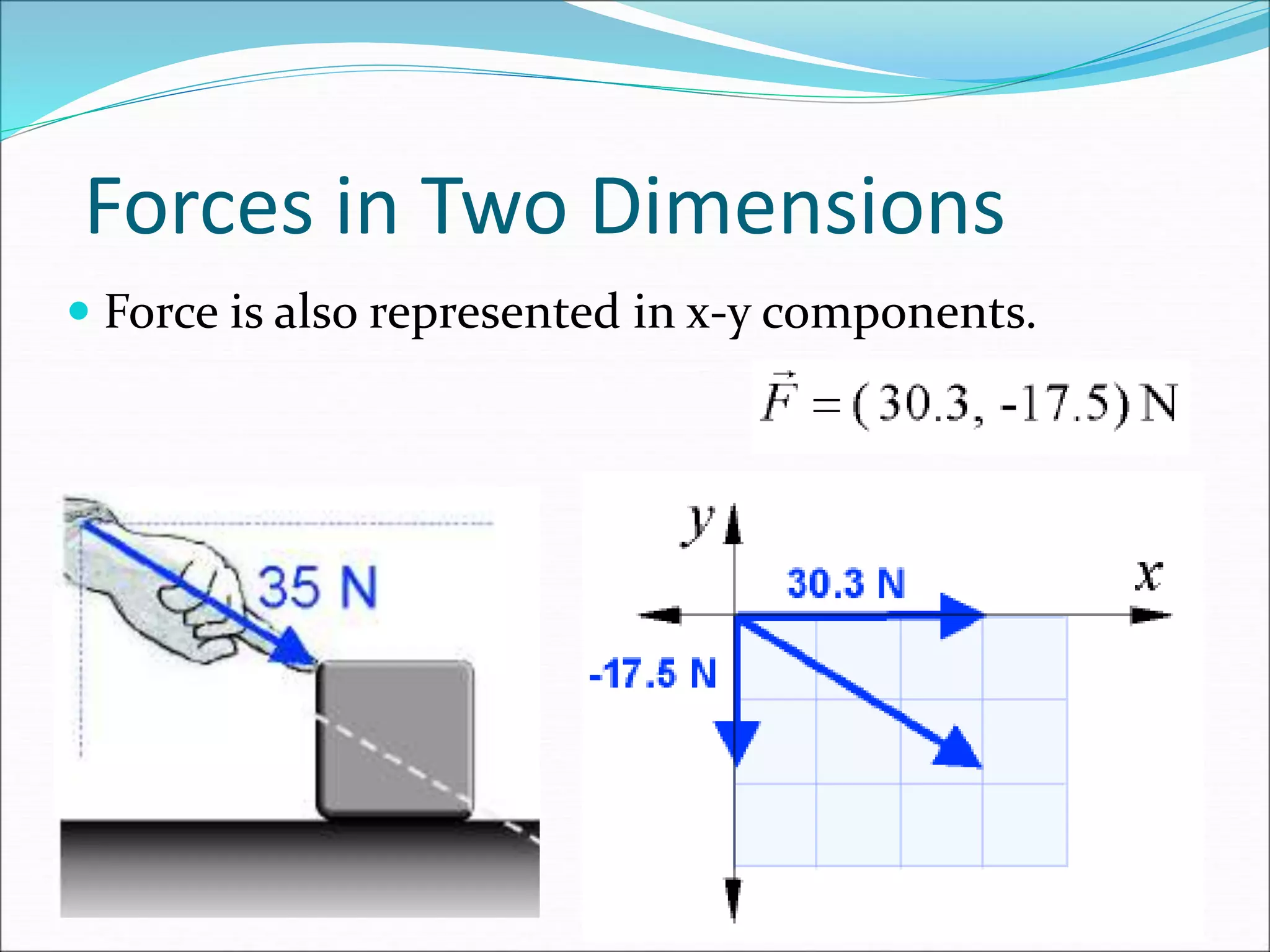

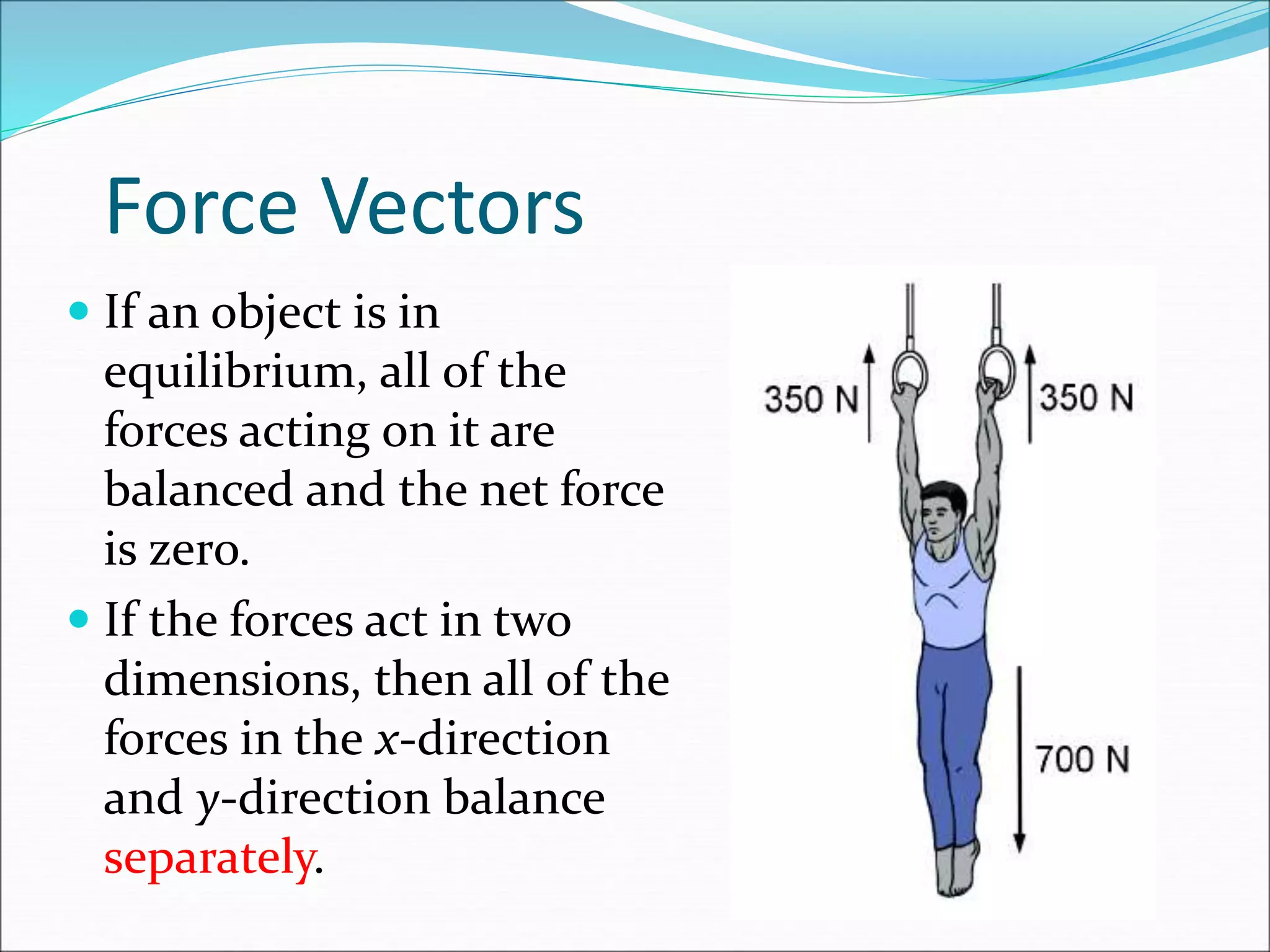

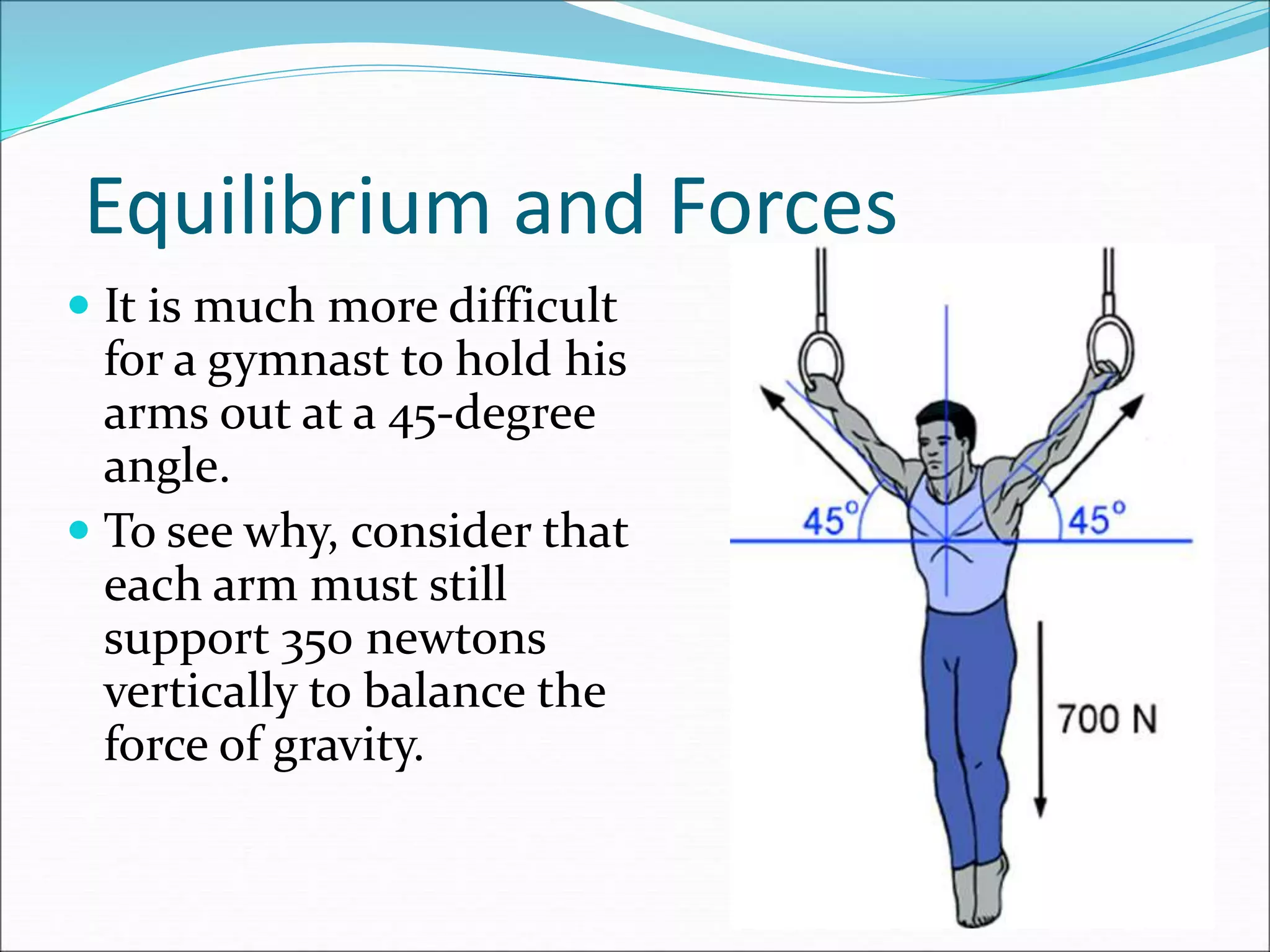

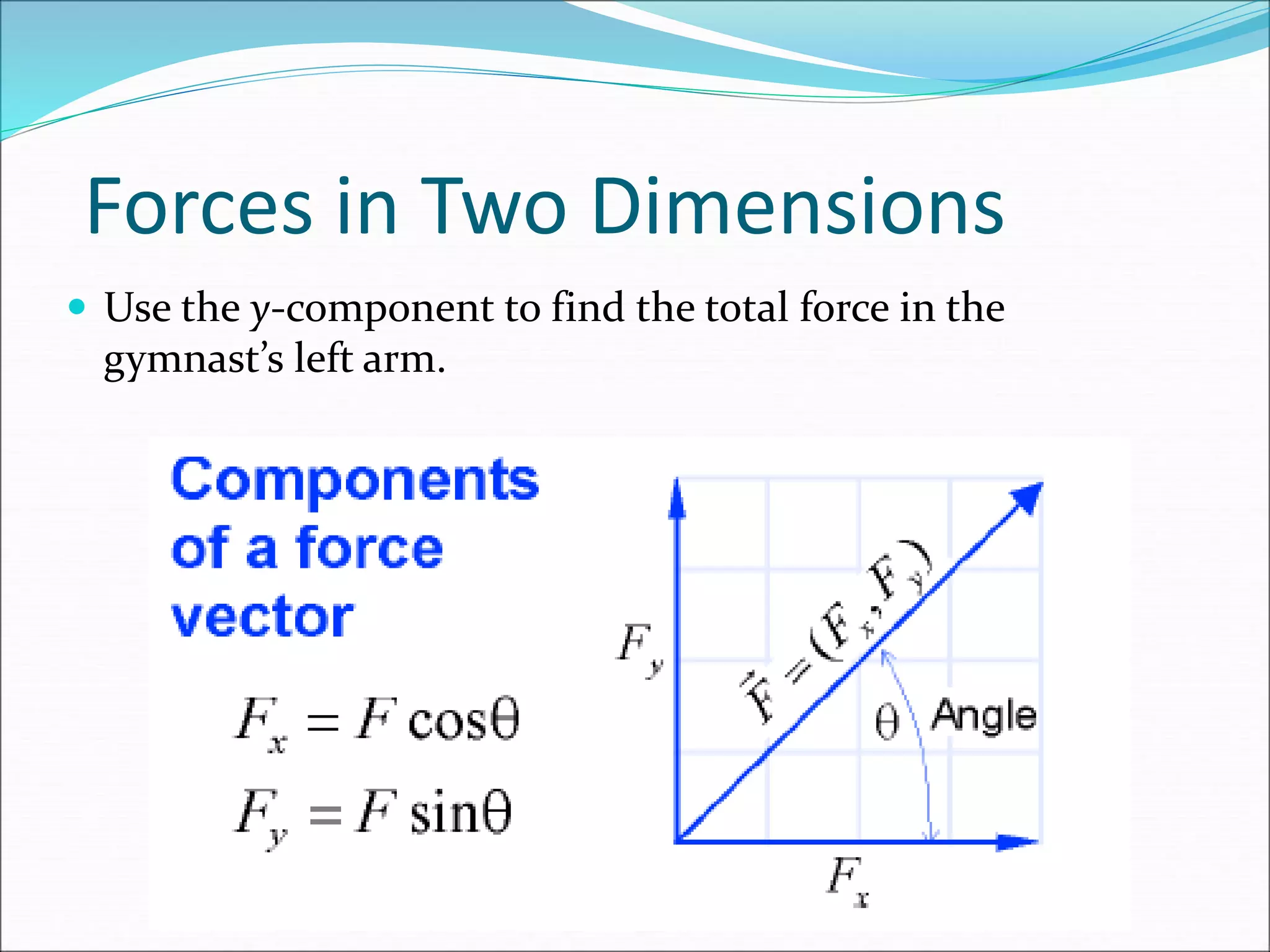

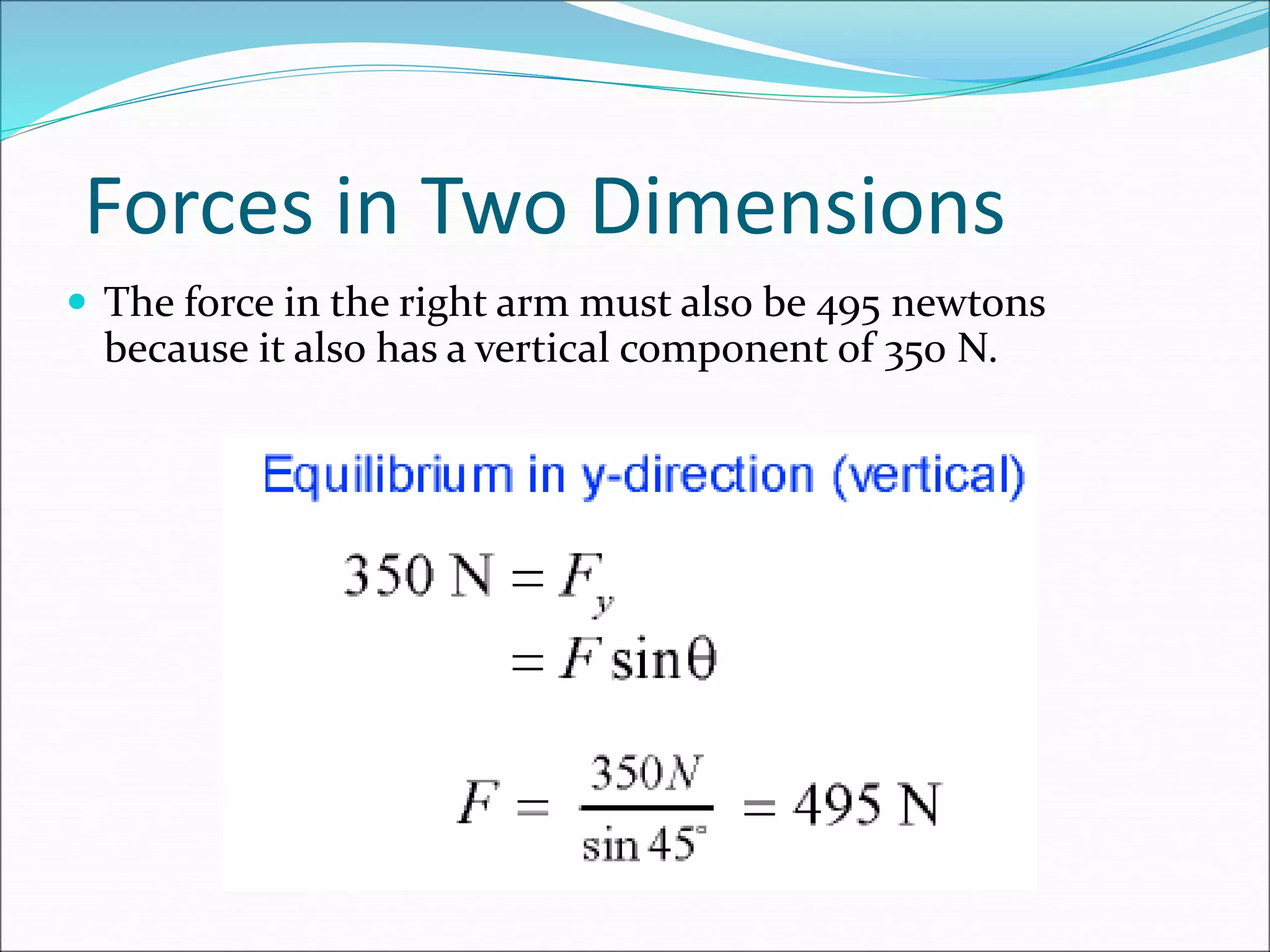

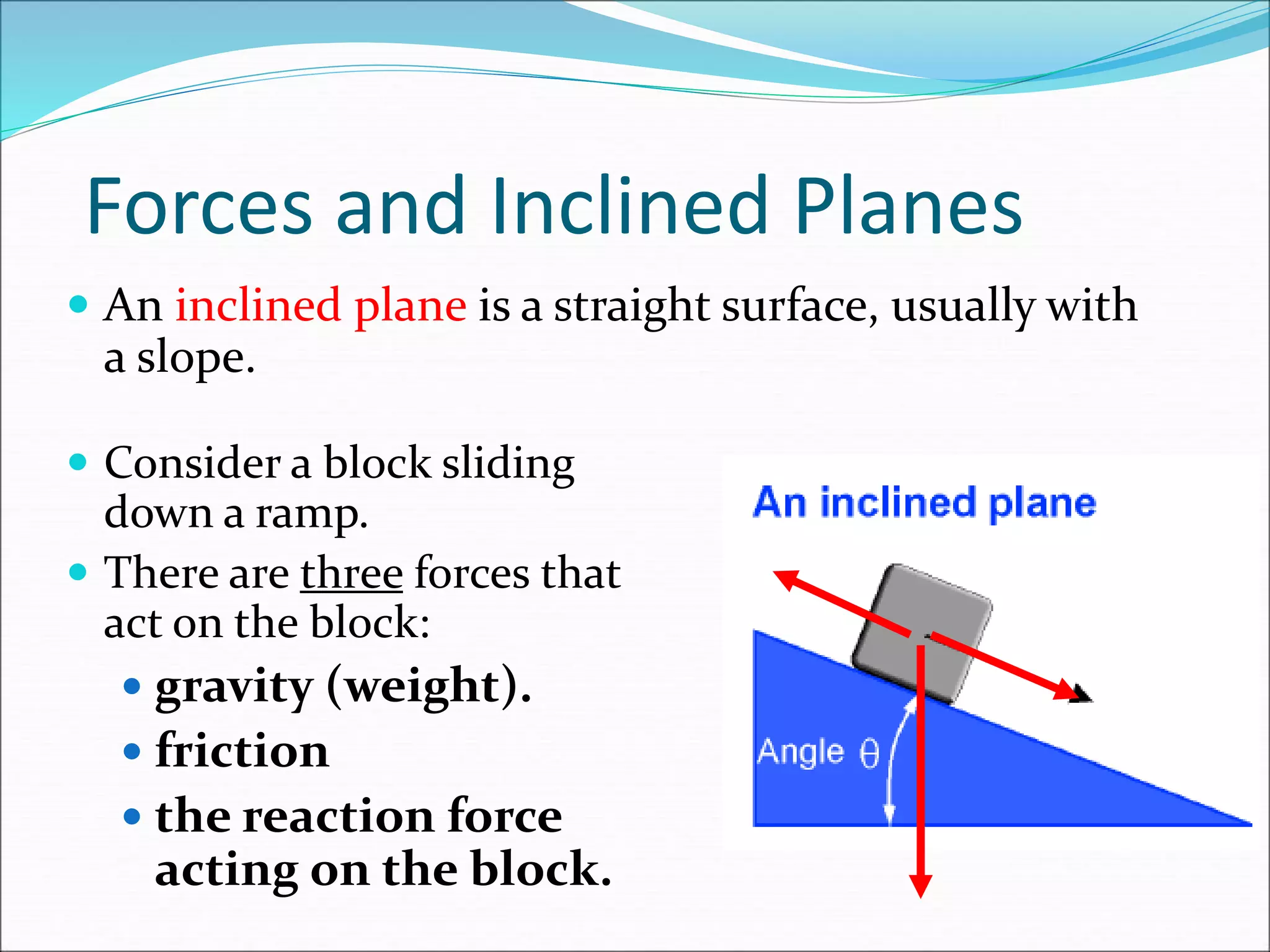

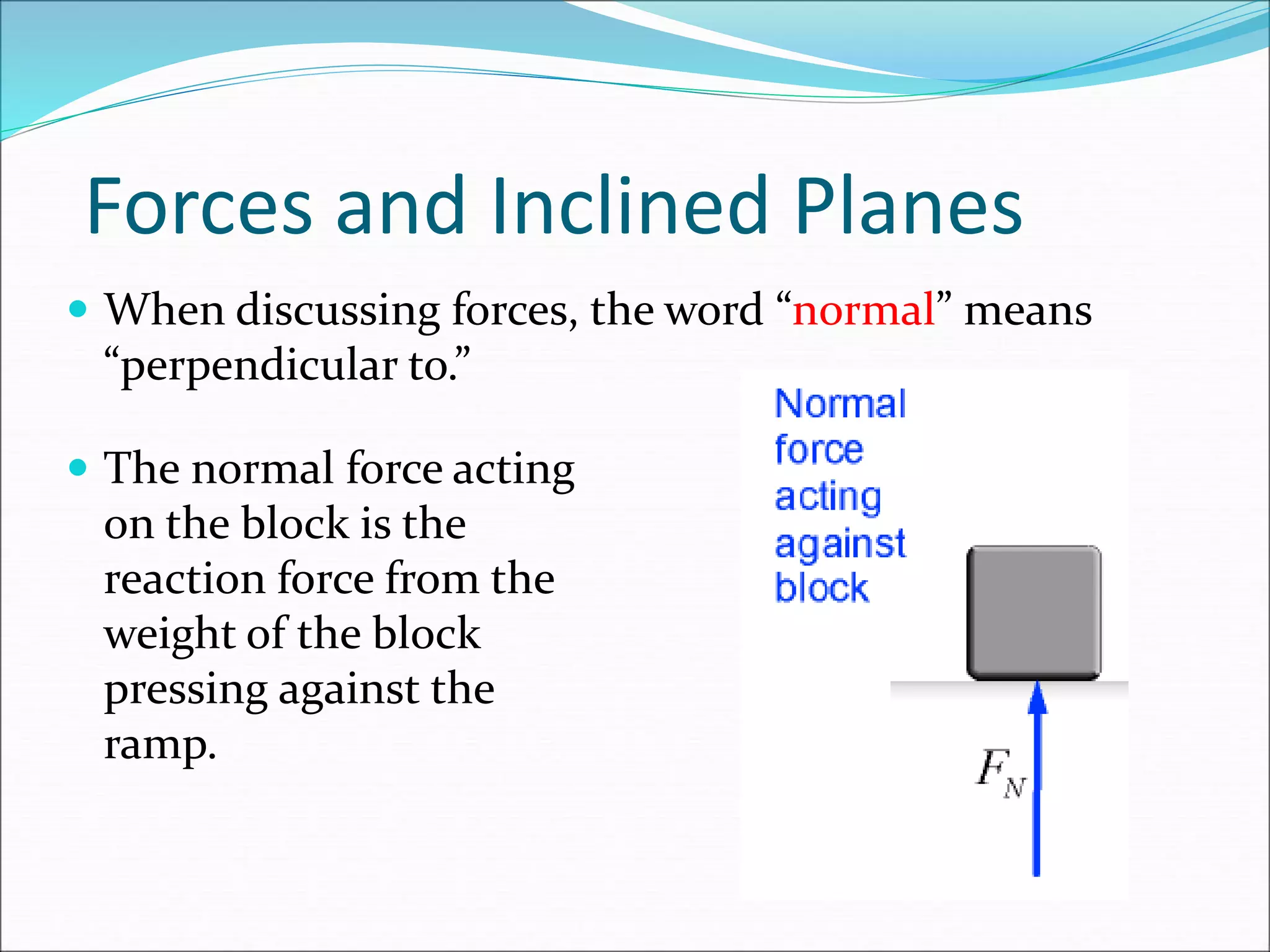

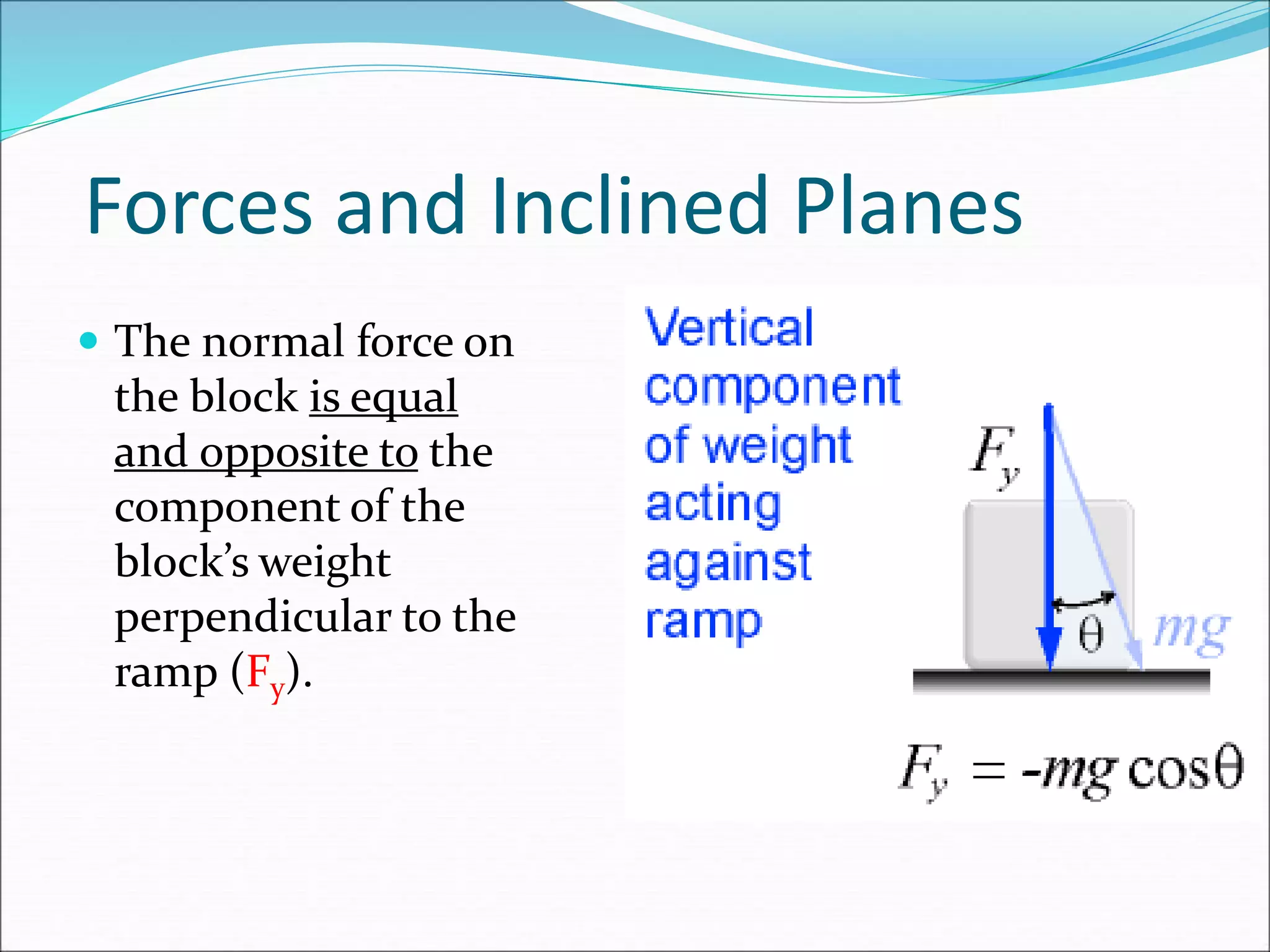

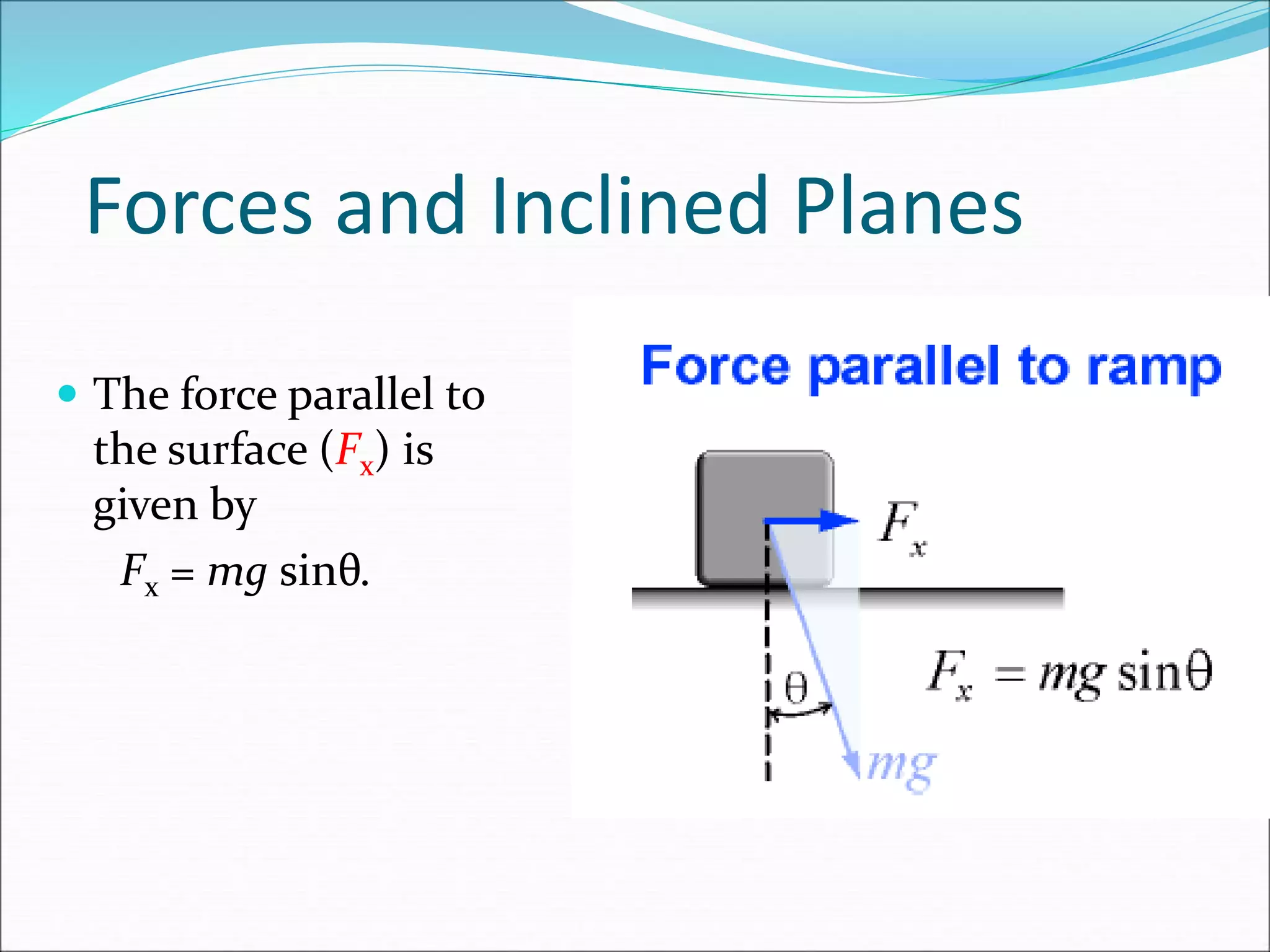

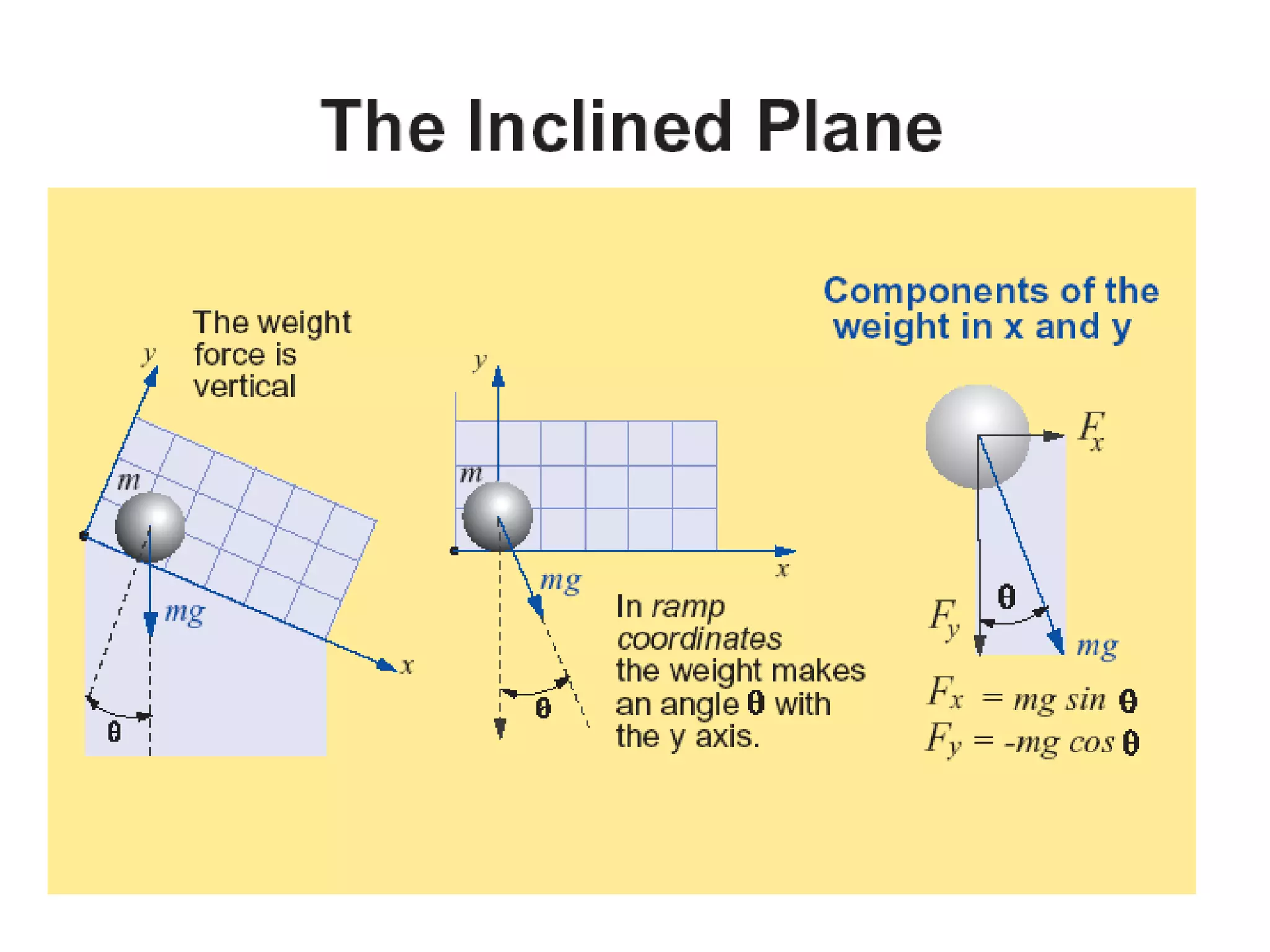

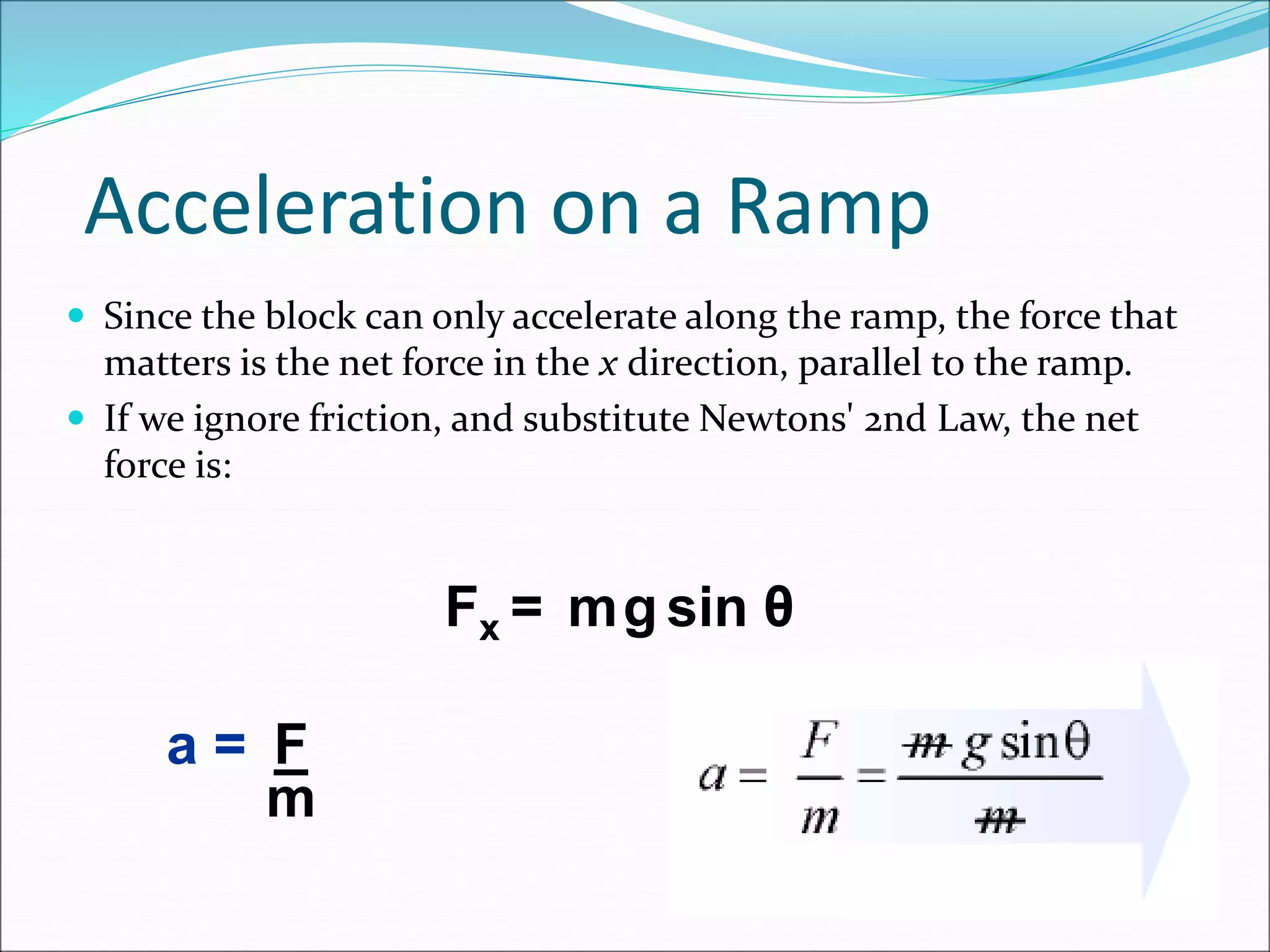

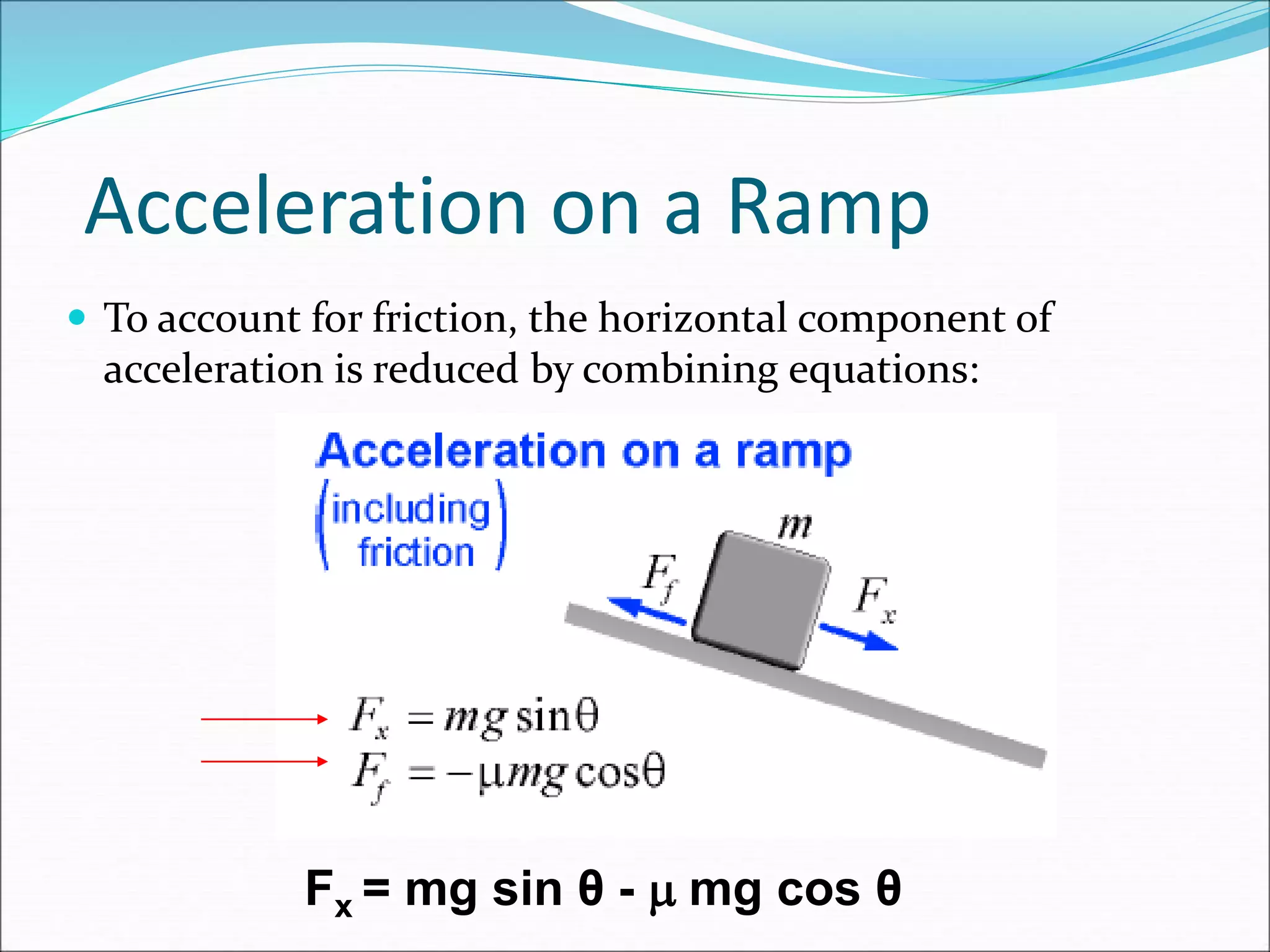

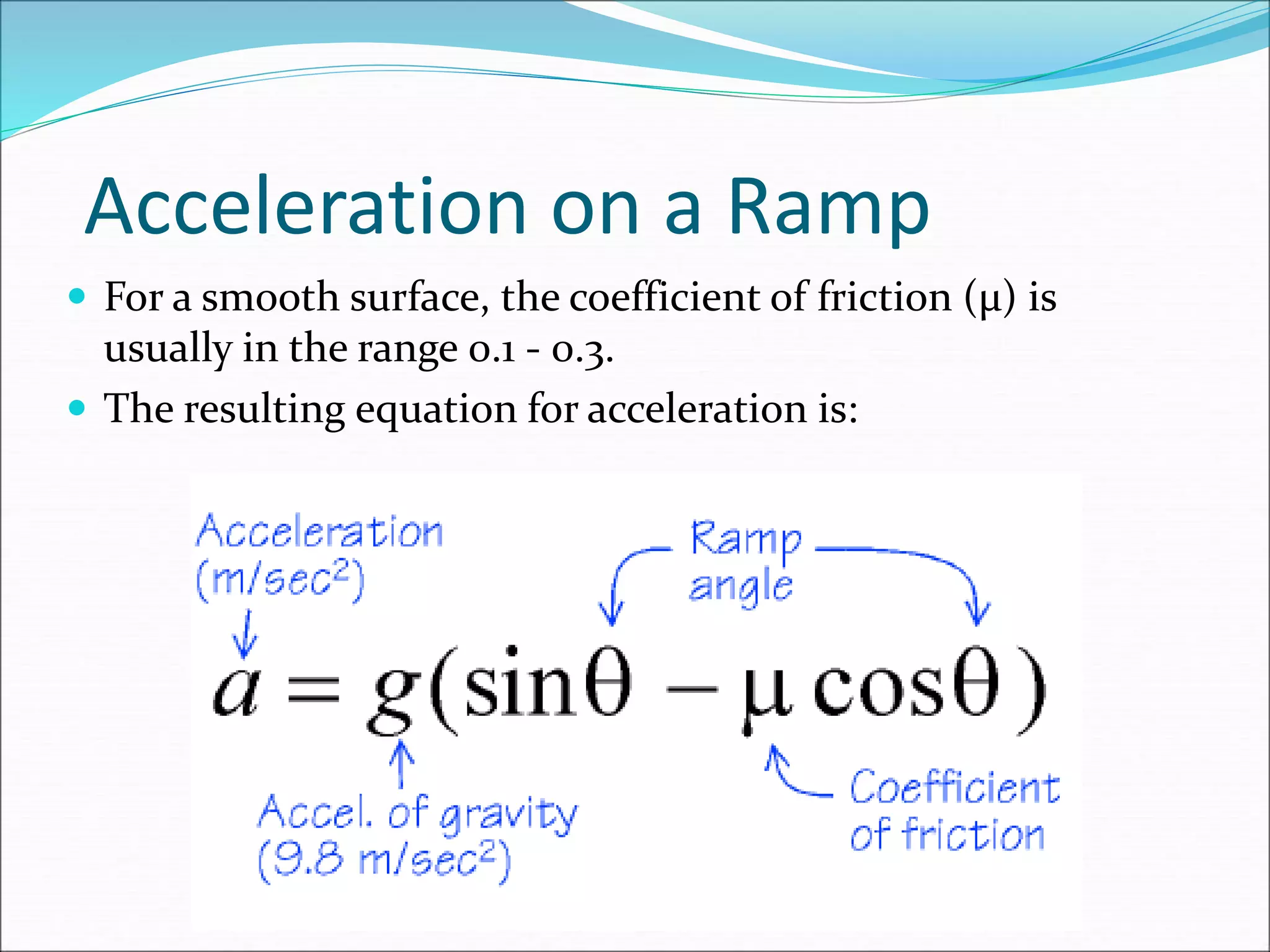

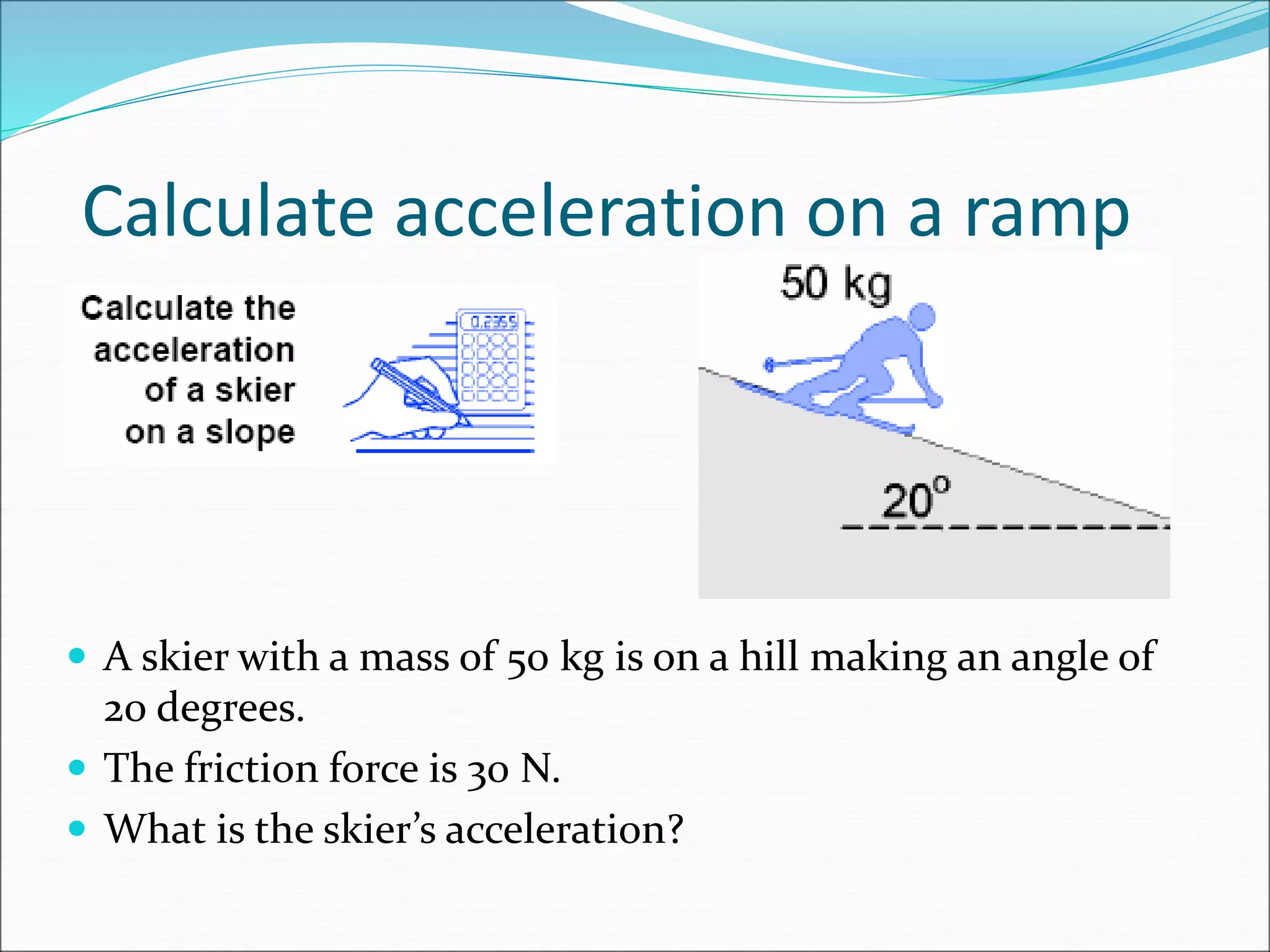

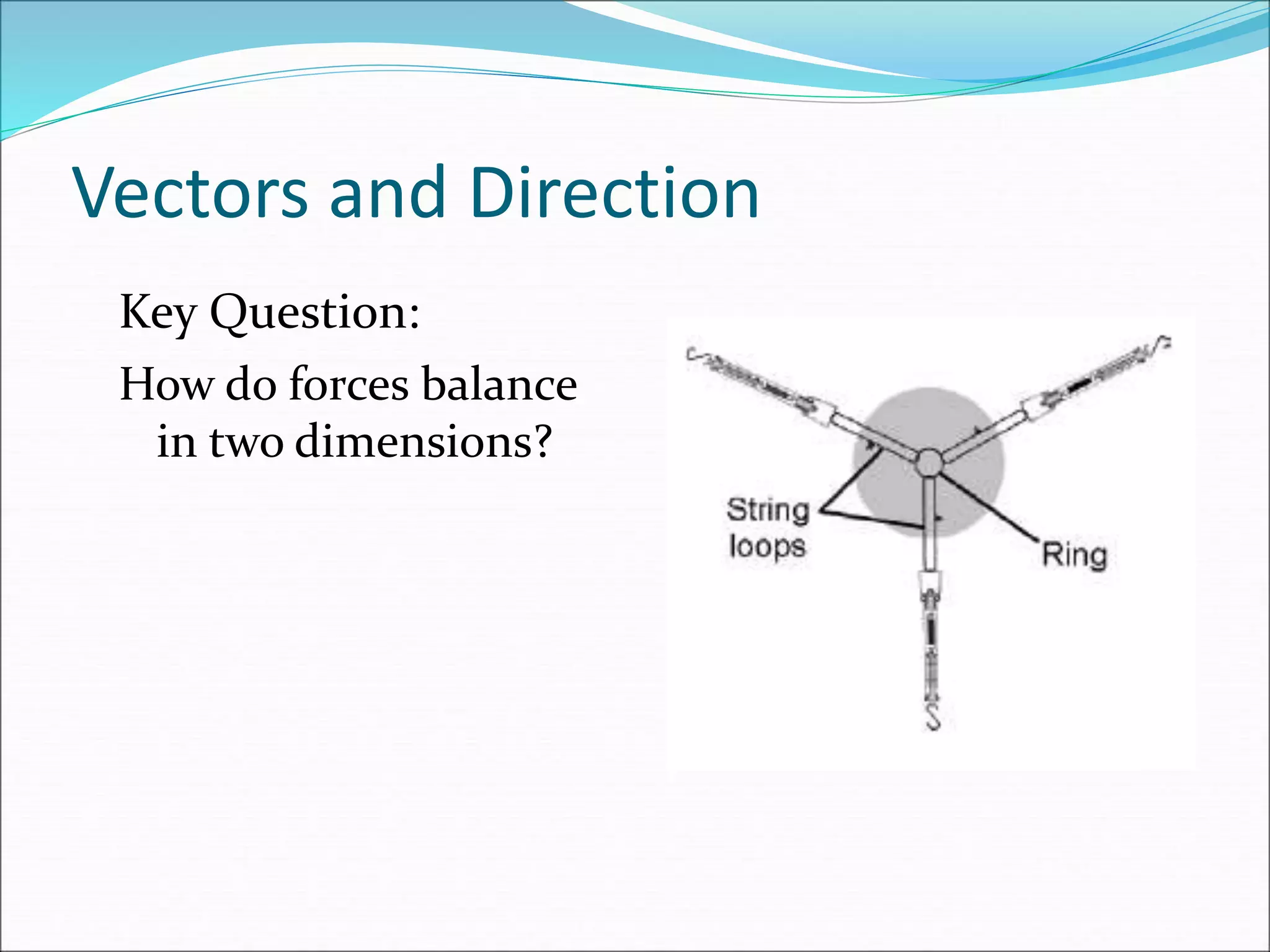

The document discusses vector concepts like displacement, velocity, and force and how to calculate their components in x and y directions. It also explains how to use vector addition and subtraction to solve problems involving projectile motion and forces in two dimensions, including calculating the acceleration on an inclined plane when given the angle of incline. The objectives cover topics like adding and subtracting vectors, writing vectors in polar and x-y coordinates, and using force vectors to solve two-dimensional equilibrium problems.