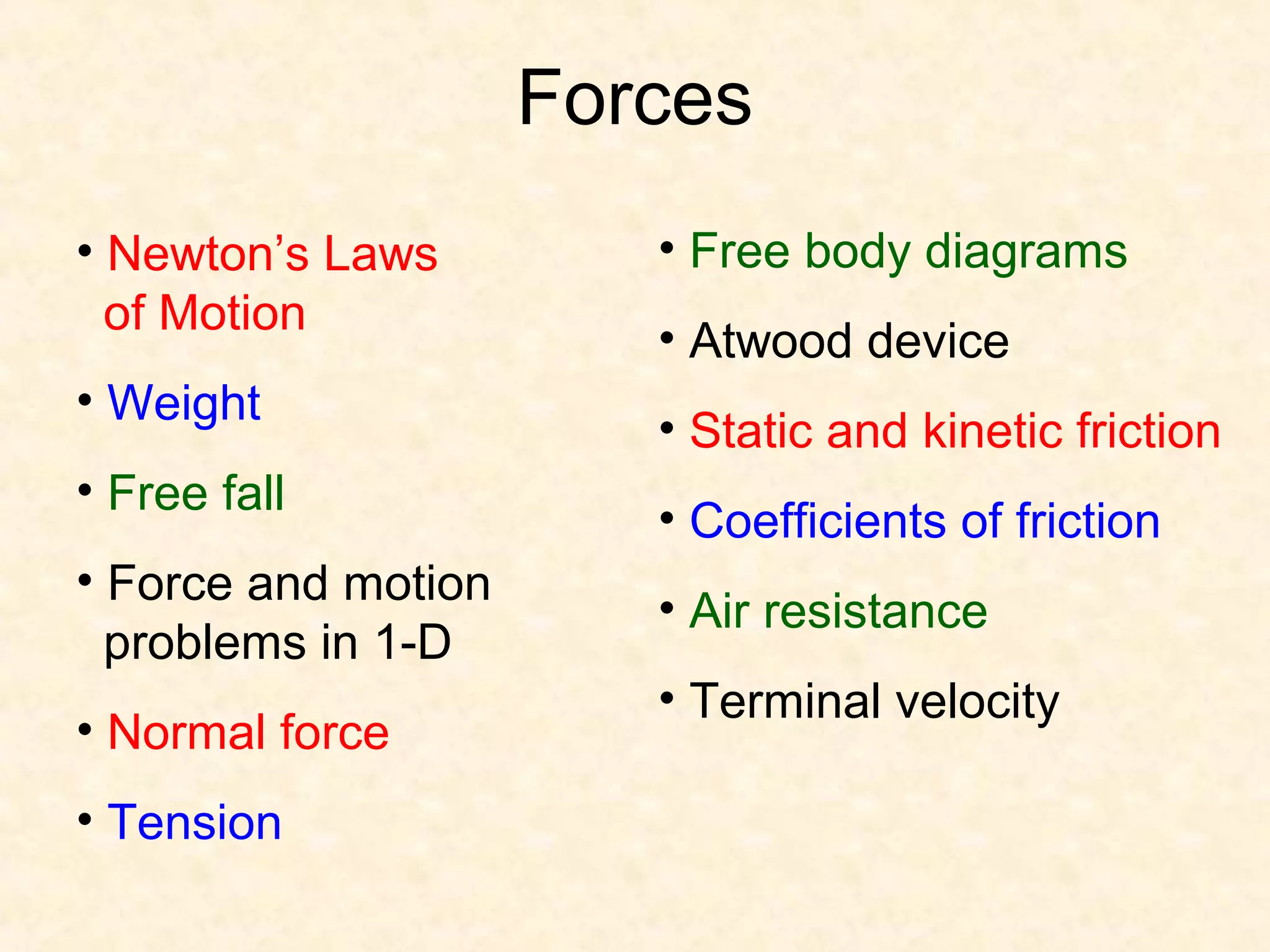

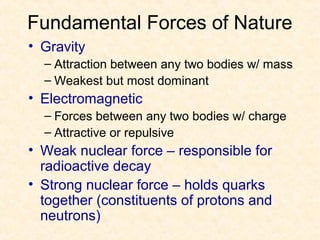

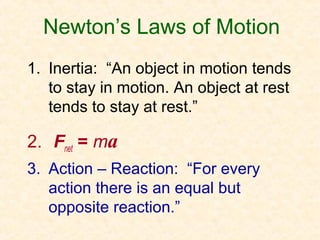

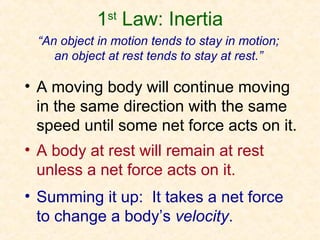

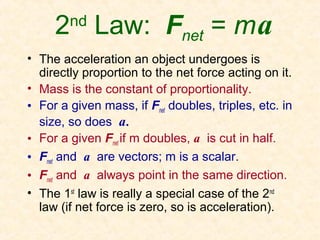

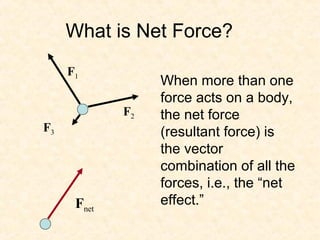

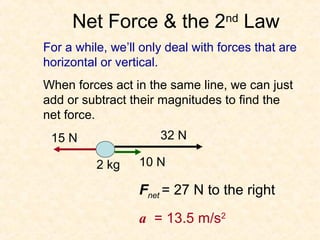

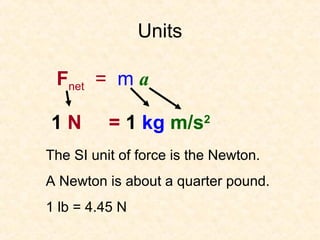

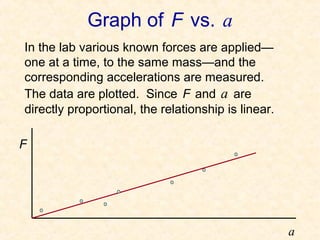

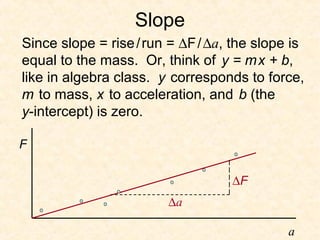

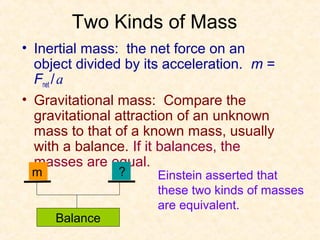

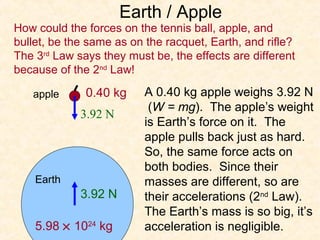

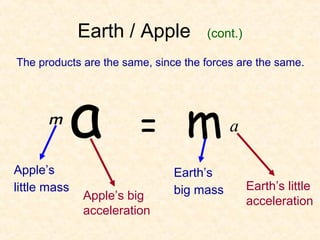

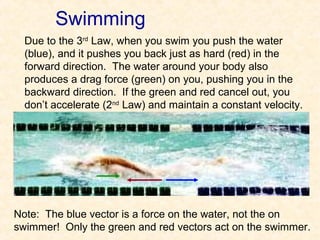

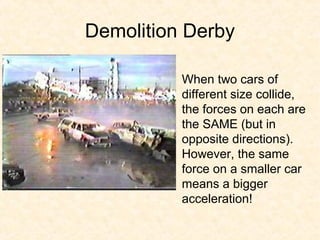

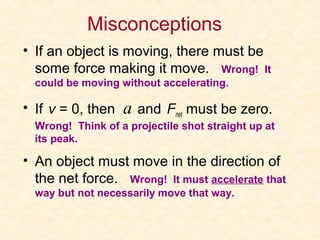

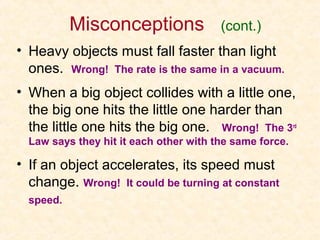

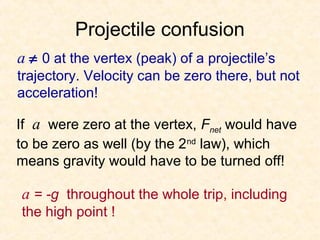

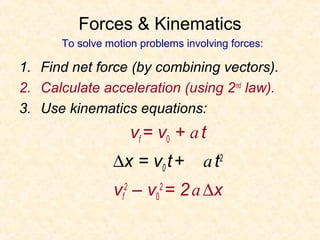

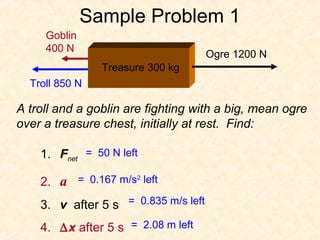

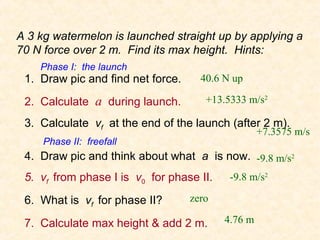

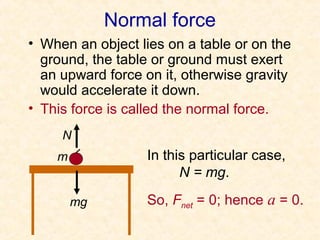

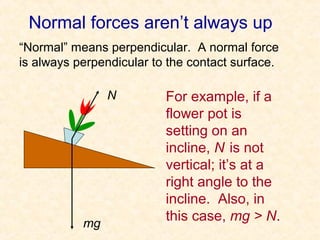

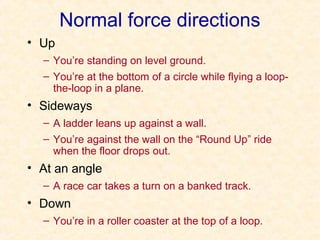

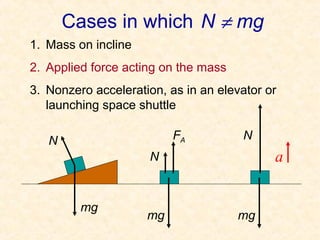

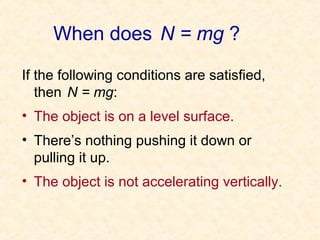

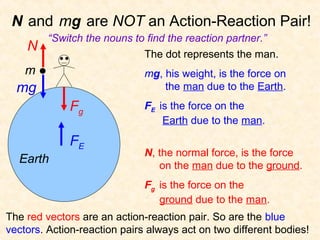

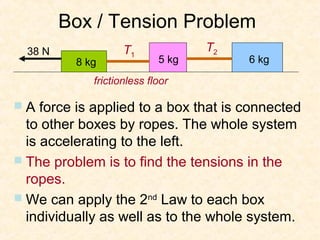

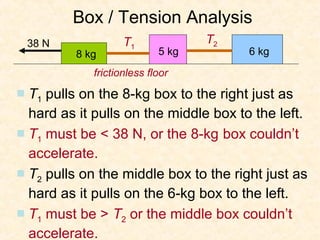

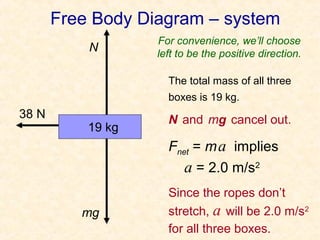

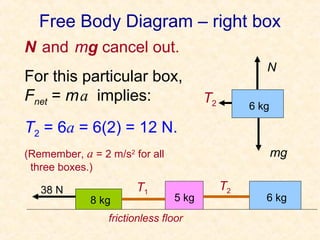

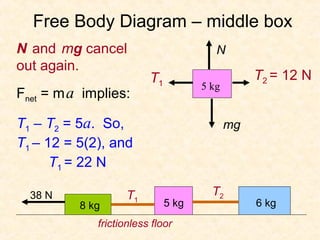

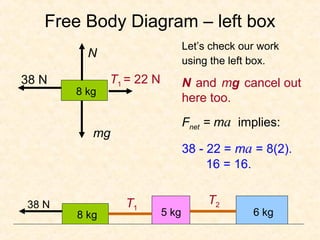

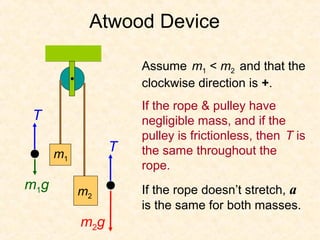

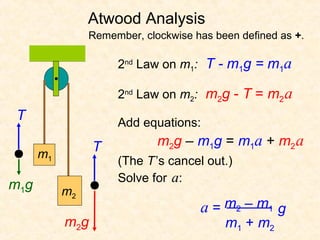

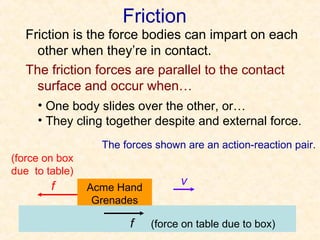

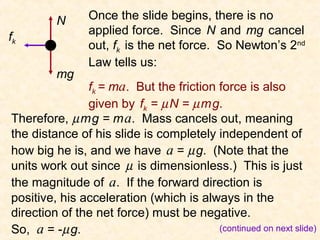

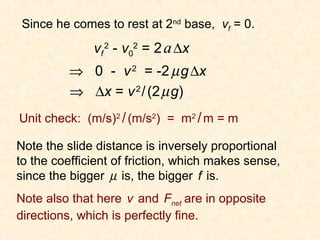

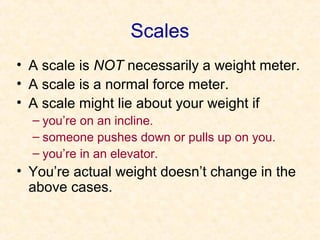

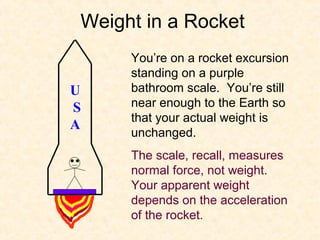

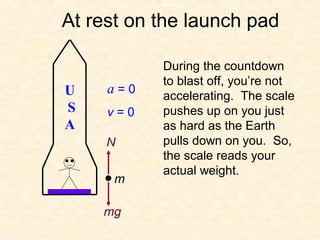

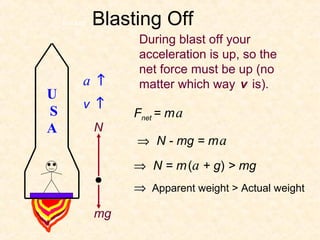

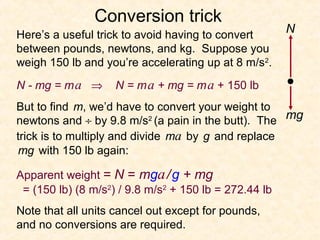

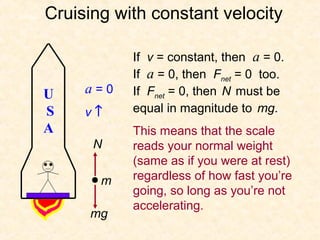

This document discusses Newton's laws of motion and provides examples of forces. It introduces Newton's three laws, including inertia, Fnet=ma, and action-reaction. Examples are given for each law such as an astronaut drifting in space (1st law), graphs of force vs. acceleration (2nd law), and collisions between objects of different masses (3rd law). Common forces like gravity, tension, and normal forces are also explained.