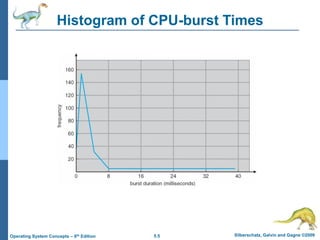

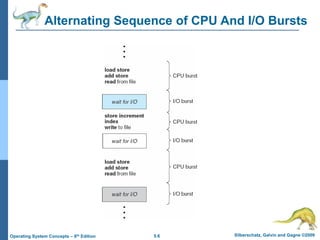

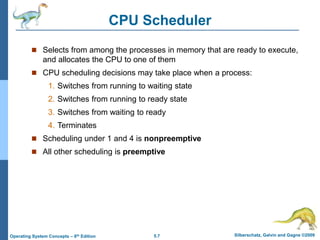

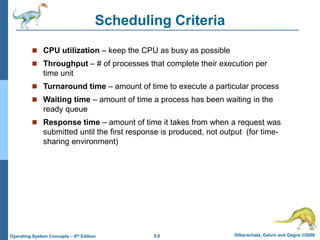

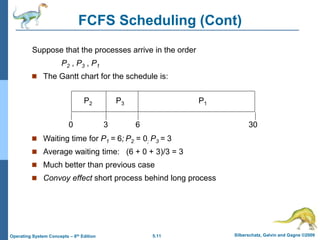

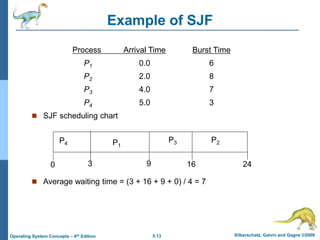

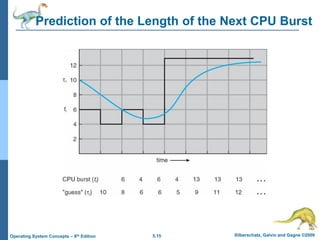

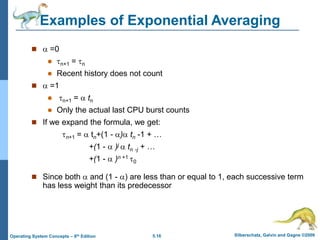

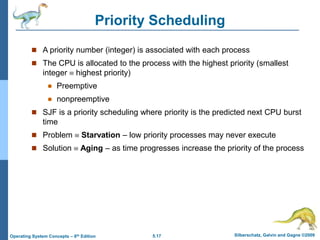

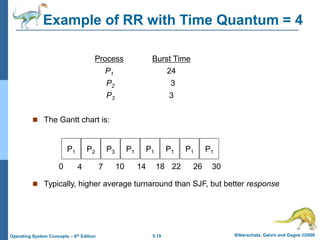

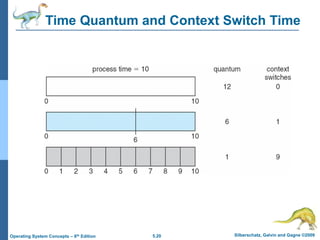

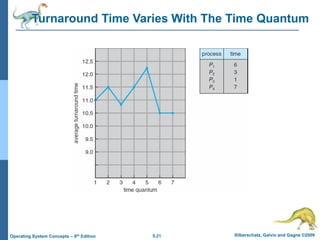

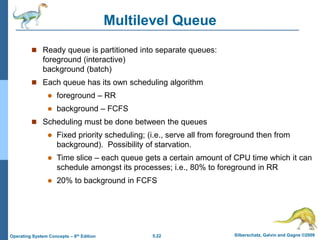

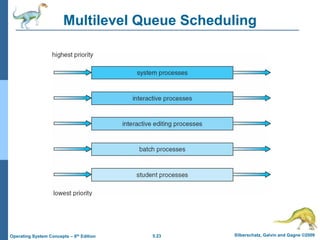

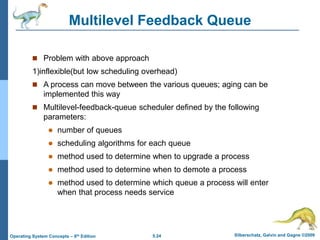

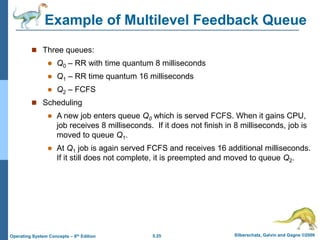

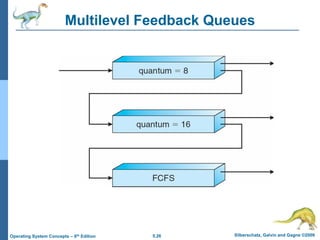

This document summarizes Chapter 5 from the textbook "Operating System Concepts - 8th Edition" by Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne. The chapter introduces CPU scheduling algorithms which are important for multiprogrammed operating systems. It describes scheduling criteria like CPU utilization and waiting time. Specific algorithms covered include first-come first-served scheduling, shortest-job-first scheduling, priority scheduling, and round robin scheduling. Advanced scheduling techniques involving multiple queues and multiple processors are also discussed.