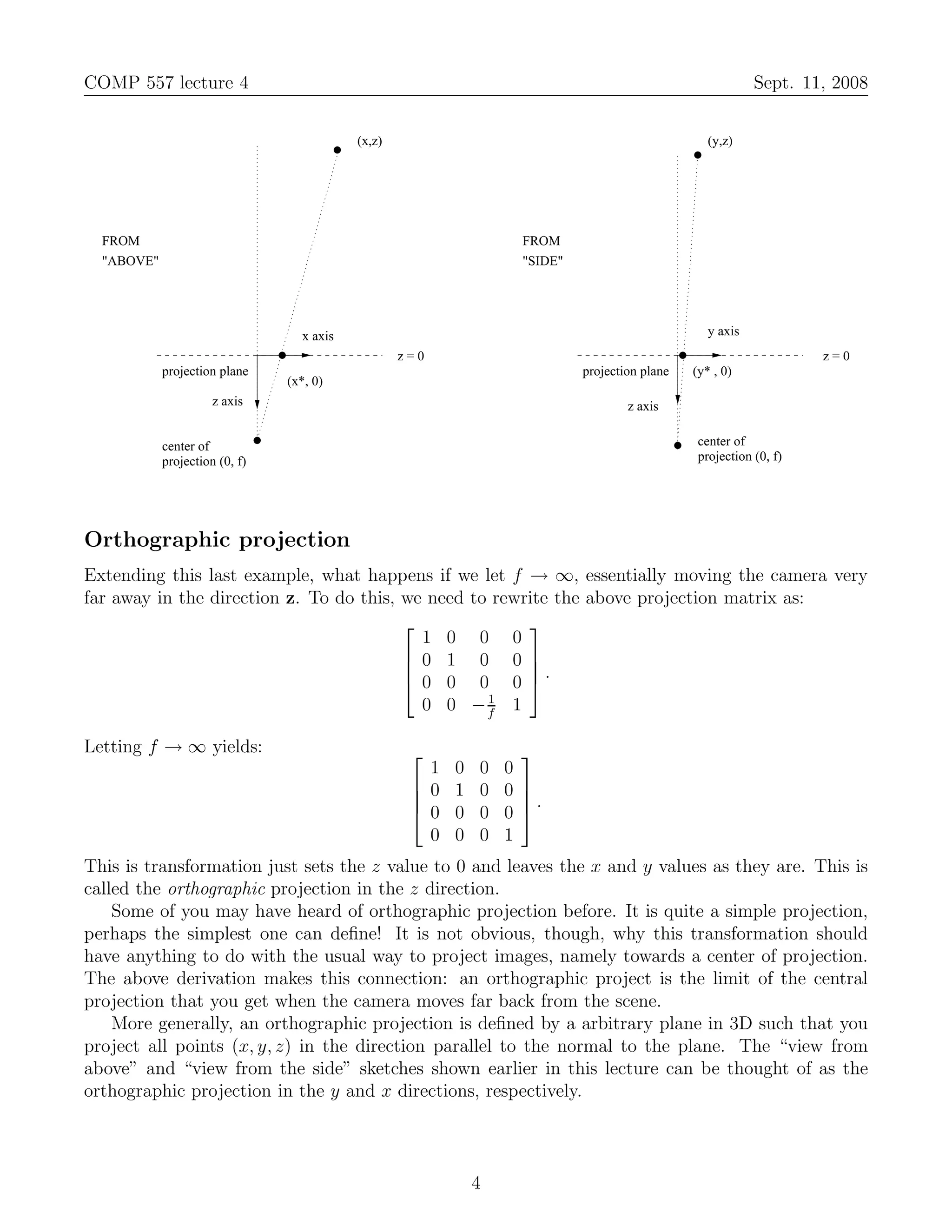

1) The document discusses perspective projection, which models image formation by projecting a 3D scene onto a 2D projection plane from a single center of projection, analogous to a camera.

2) It introduces homogeneous coordinates to represent 3D points as 4D vectors, allowing perspective transformations to be represented by 4x4 matrices.

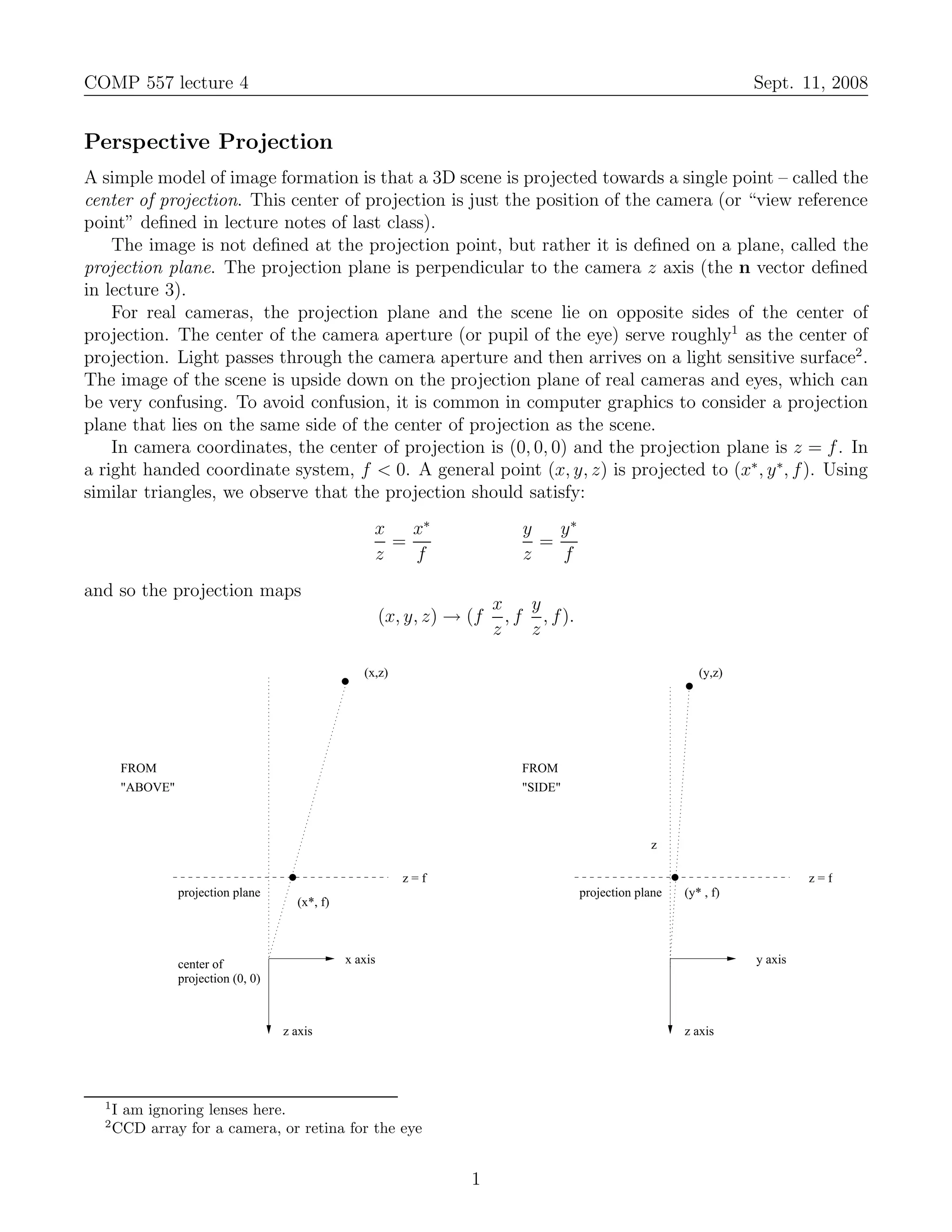

3) Two examples of perspective projections are shown - onto the plane z=f, and onto z=0 with the center of projection at (0,0,f). 4x4 matrices representing these transformations are derived.

![COMP 557 lecture 4 Sept. 11, 2008

Homogeneous coordinates

Last class we have represented a 3D point (x, y, z) as a point (x, y, z, 1) in ℜ4 . We now generalize

this by representing (x, y, z) as any 4D vector of the form (wx, wy, wz, w) where w = 0. Note that

the set of points

{ (wx, wy, wz, w) : w = 0 }

is a line in ℜ4 which passes through the origin and the point (x, y, z, 1) in ℜ4 . [ASIDE: note we are

associating each point in ℜ3 with a line in ℜ4 , in particular, a line that passes through the origin.]

Is this generalization consistent with the 4 × 4 rotation, translation, and scaling matrices which

we introduced last class. Yes, it does, since for any q = (x, y, z, 1),

w(Mq) ≡ M(wq),

that is, multiplying each component of the vector q by w and transforming by M yields the same

vector as transforming q by M and then muliplying each component of M q by w. But multiplying

each component of a 4D vector by w doesn’t change the 3D point that is represented.

But what do we gain in identifying (x, y, z, 1) with (wx, wy, wz, w) ? Answer: alot. For example,

consider the projection mapping above. We re-write our projected points as follows:

x y

(f , f , f, 1) ≡ (xf, yf, f z, z).

z z

This allows us to represent the projection transformation by a 4 × 4 matrix, i.e. :

fx f 0 0 0 x

fy 0 f 0 0 y

fz = 0 0 f 0 z

z 0 0 1 0 1

Several observations can be made. First, since we are now treating all 4D points (wx, wy, wz, w)

as representing the same 3D point, we can multiply any 4 × 4 transformation matrix by a constant,

without changing the transformation that is carried out by the matrix. The above matrix can be

divided by the constant f and written instead as:

1 0 0 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 1 0

1

0 0 f 0

This matrix, like the one above, projects the 3D scene onto the plane z = f , with center of projection

being the origin (0, 0, 0).

A second observation is that, whereas the 4 × 4 translation, rotation, and scaling matrices were

invertible (and hence of rank 4), the projection matrix is clearly not invertible. It is of rank 3 since

the third and fourth rows are linearly dependent i.e. they differ only by a multiplicative constant.

A third observation is that there is nothing magic about the z = f projection plane. We can

easily define projections onto other planes. For example, the following matrix projects onto the

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cg-110930070607-phpapp02/75/Cg-2-2048.jpg)