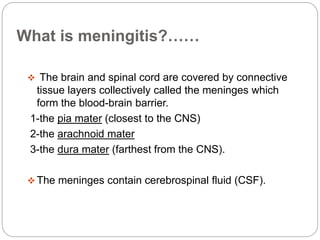

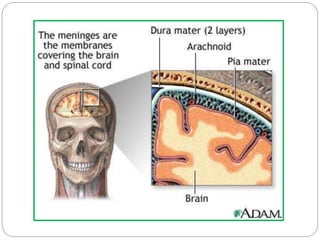

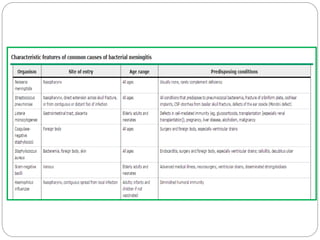

Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges, the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. It is caused by bacterial, viral, or fungal infections. The classic symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Diagnosis involves examination of cerebrospinal fluid which shows increased white blood cells and decreased glucose levels in bacterial meningitis. Treatment depends on the identified pathogen but generally involves antibiotics. Adjunctive steroids may reduce complications for some types of bacterial meningitis. Outcomes vary depending on the cause, but bacterial meningitis can have mortality rates around 20% even with treatment.

![Role Of Steroids:

dexamethasone reduces cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

concentrations of cytokines (such as tumor necrosis factor

[TNF]-alpha and interleukin [IL]-1), CSF inflammation, and

cerebral edema](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/casepresentationmeningitis-180610065229/85/Case-presentation-meningitis-and-treatment-Moh-d-Sharshir-41-320.jpg)

![ In patients with known or suspected

pneumococcal meningitis who are treated

with dexamethasone, we suggest

adding rifampin to the standard antibiotic regimen

(vancomycin plus

either ceftriaxone or cefotaxime) if susceptibility

studies show intermediate susceptibility

(minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC]

≥2 mcg/mL) to ceftriaxone and cefotaxime (Grade

2C). A reasonable alternative is to initiate rifampin

and then discontinue it if the isolate is susceptible

to the cephalosporin. (See 'Antibiotic

regimens' above.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/casepresentationmeningitis-180610065229/85/Case-presentation-meningitis-and-treatment-Moh-d-Sharshir-45-320.jpg)

![ In a prospective study of 86 adults with bacterial

meningitis, cerebral angiography was performed

in 27 (31 percent) because one or more of the

following findings were present: focal neurologic

deficits, abnormalities on computed tomographic

(CT) scanning, or persistent coma after three

days of antibiotic therapy [16]. Abnormal

angiograms were found in 13 of these 27

patients; the abnormal findings included:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/casepresentationmeningitis-180610065229/85/Case-presentation-meningitis-and-treatment-Moh-d-Sharshir-49-320.jpg)

![ In another report, a cranial CT scan was

performed in 87 of 122 adults with bacterial

meningitis seen after 1975 [2]. A cerebral infarct

was noted in four, lesions consistent with septic

emboli in two and cavernous sinus thrombosis in

one. Four patients without a lesion on initial scan

had signs of an infarct on a later CT scan that

was performed because of persistent hemiparesis

in three and triplegia in one](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/casepresentationmeningitis-180610065229/85/Case-presentation-meningitis-and-treatment-Moh-d-Sharshir-51-320.jpg)

![Management and Treatment :

Anticoagulation:

In a nonrandomized case-control study, a greater proportion of

adult patients treated with LMWH (n = 119) compared with

unfractionated heparin (n = 302) were independent at six months

(92 versus 84 percent, adjusted odds ratio 2.4, 95% CI 1.0-5.7)

[33]. Treatment with LMWH was also associated with slightly

lower rates of mortality (6 versus 8 percent) and new intracranial

hemorrhage (10 versus 16 percent), but these outcomes were

not statistically significant

Unfractionated or low-molecular weight

heparin for the treatment of cerebral

venous thrombosis. Stroke.

2010;41(11):2575.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/casepresentationmeningitis-180610065229/85/Case-presentation-meningitis-and-treatment-Moh-d-Sharshir-113-320.jpg)