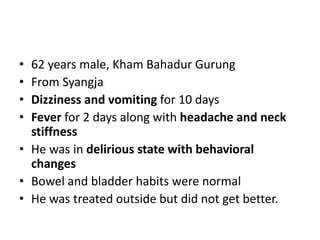

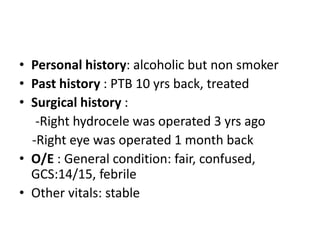

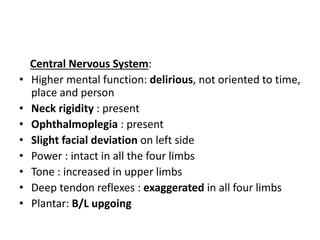

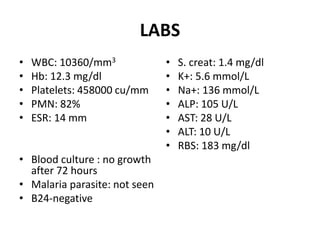

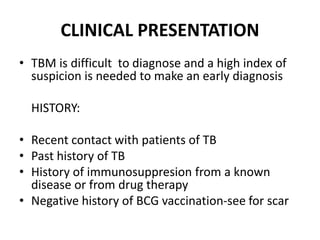

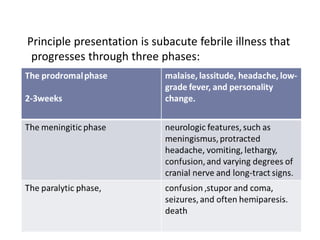

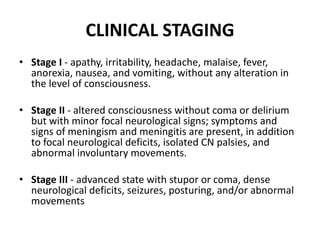

1. A 62-year-old man presented with 10 days of dizziness, vomiting, and 2 days of fever and headache. Examination revealed neck stiffness, delirium, and signs of meningitis.

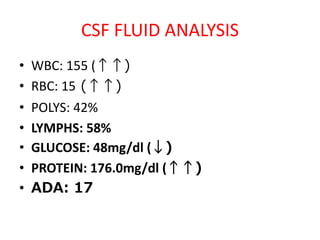

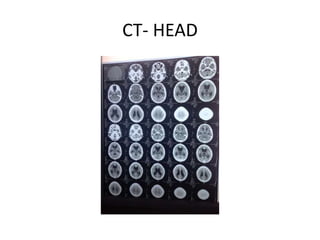

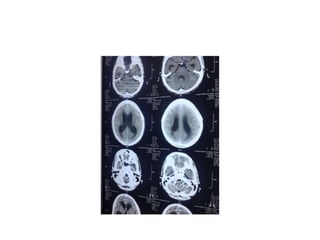

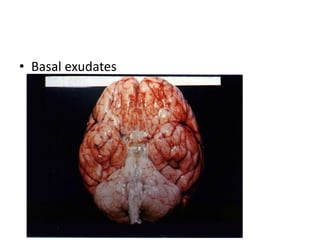

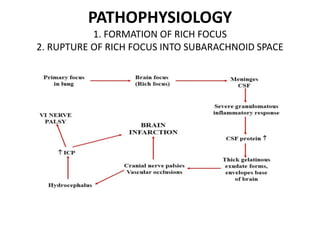

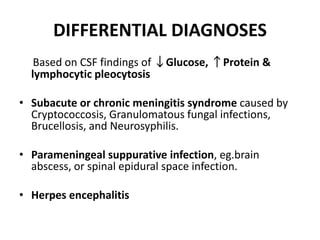

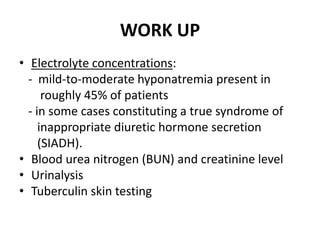

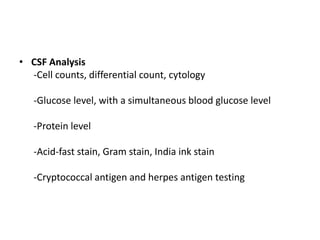

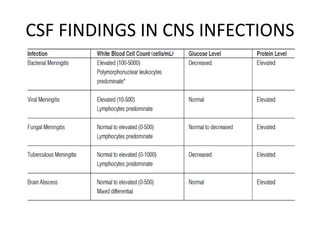

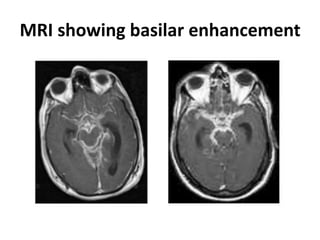

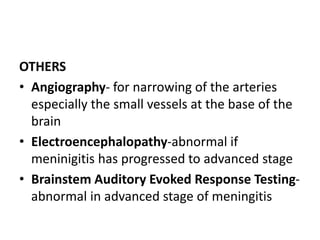

2. CSF analysis showed elevated white blood cells and protein with low glucose, consistent with tuberculous meningitis. CT head and MRI brain showed basilar enhancement.

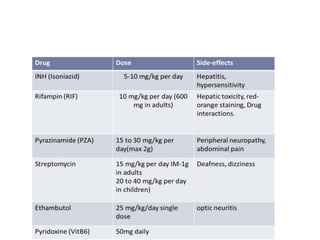

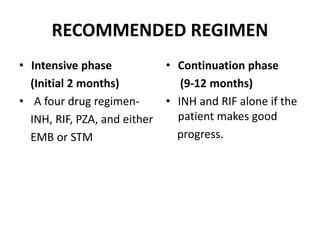

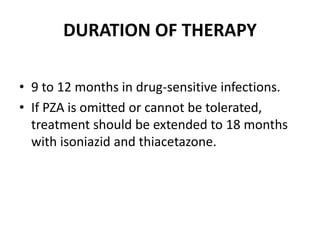

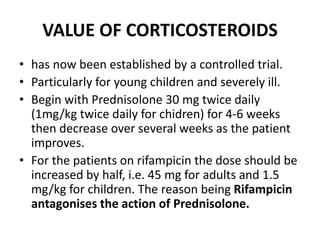

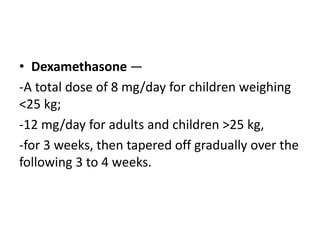

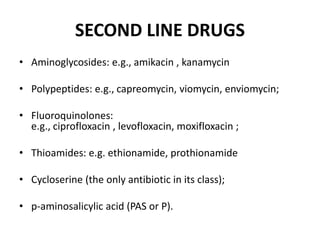

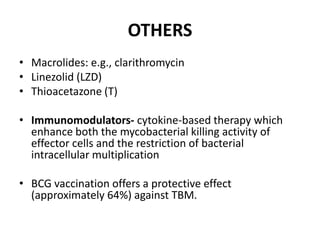

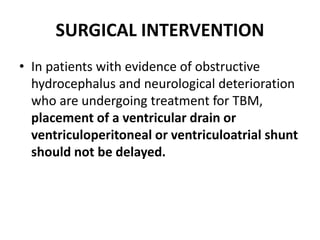

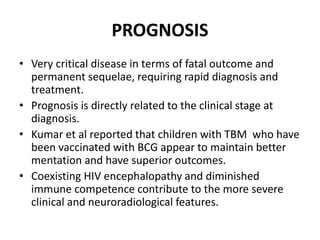

3. Tuberculous meningitis was diagnosed and treatment initiated with a four drug antitubercular regimen along with corticosteroids. Prognosis depends on stage at diagnosis and risk factors like HIV co-infection impact outcomes.