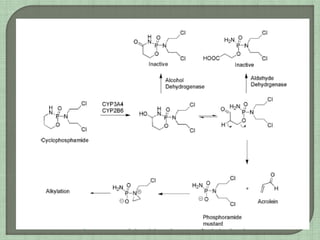

The document summarizes the mechanisms of action and properties of alkylating agents, a class of chemotherapy drugs that work by forming covalent bonds with DNA and other biomolecules. It discusses how alkylation of DNA can lead to cell death through disruption of DNA function and apoptosis. However, cancer cells can become resistant through mechanisms like dysfunctional p53 or DNA repair pathways. The document also describes specific alkylating agents like nitrogen mustards, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide and their mechanisms of activation and metabolism.

![ The first of these, cisplatin, was discovered by Barnett

Rosenberg as a result of experiments investigating the role

of electrical current on cell division.

Escherichia coli cells in an ammonium chloride solution had

an electrical current applied through platinum electrodes. It

was subsequently found that cell division was inhibited but

not as a result of the current but from the reaction of the

ammonium chloride with what was thought to be an inert

platinum electrode. Further investigation led to the

identification of cis-[PtCl2(NH3)2] as the active species and

mechanistic studies revealed that after administration of the

agent to mammals, the dichloro species is maintained in the

blood stream as a result of the relatively high chloride

concentration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anticanceragentsnitrogenmustards-180518095042/85/cancer-anticancer-agents-40-320.jpg)

![ The first of these involves dechlorination,

which is facilitated by CYP participation and

involves cyclization to give 4,5-dihydro-

[1,2,3]oxadiazole and the isocyanate, which

is still capable of carbamylating proteins.

The oxadiazole can be further degraded by

hydrolysis to give several inactive products.

The second route involves denitrosation,

which in the case of BCNU (carmustine) has

been shown to be catalyzed by CYP

monooxygenases and glutathione-S-

reductase](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anticanceragentsnitrogenmustards-180518095042/85/cancer-anticancer-agents-46-320.jpg)