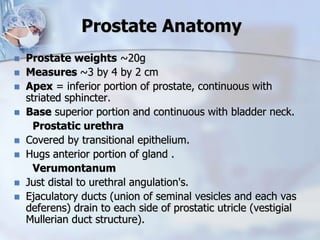

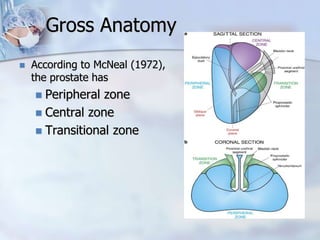

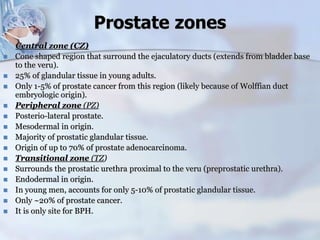

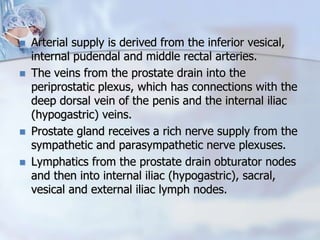

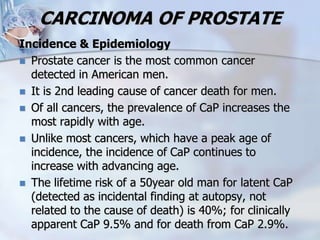

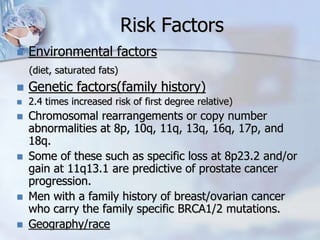

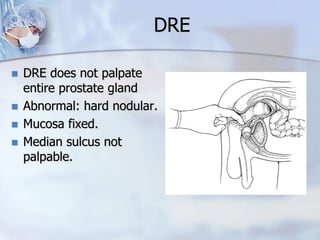

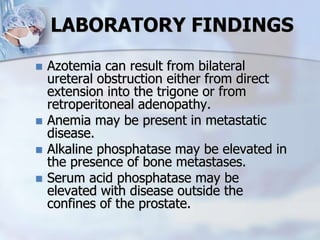

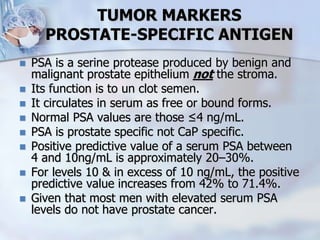

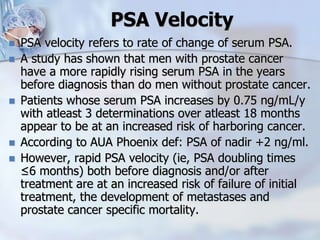

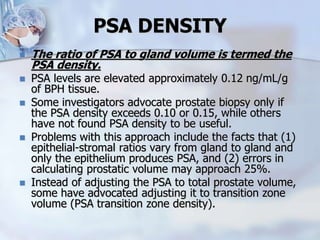

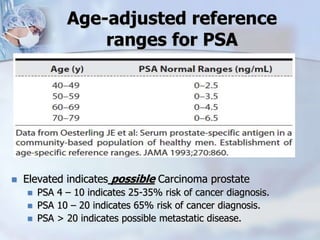

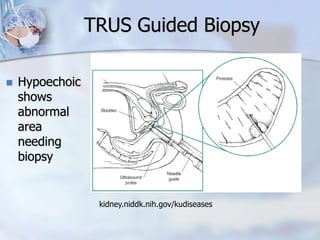

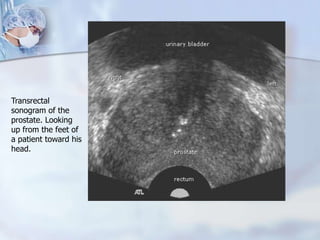

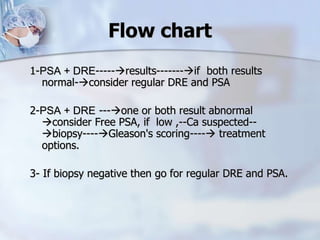

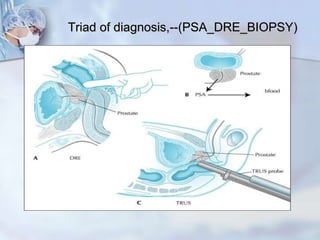

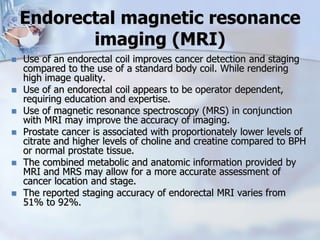

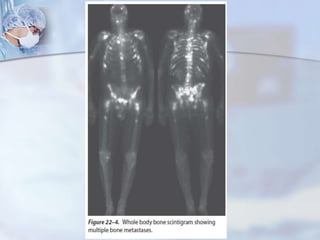

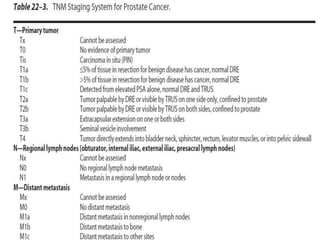

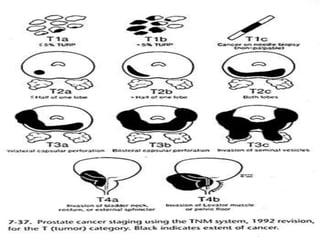

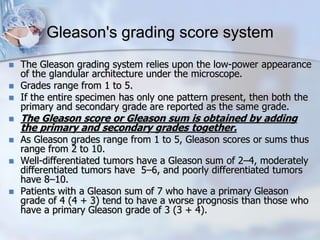

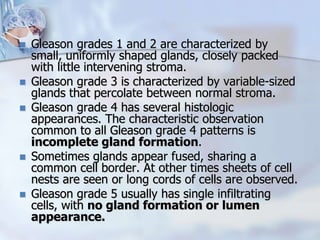

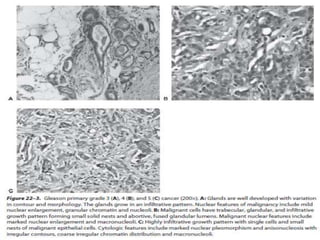

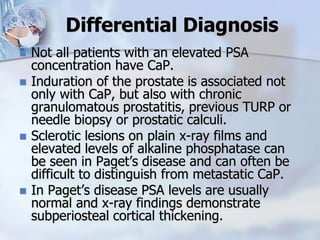

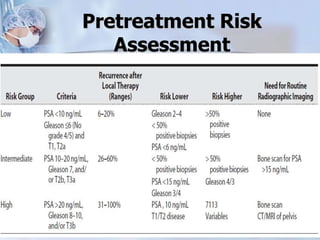

The document provides information on the anatomy and function of the prostate gland. It discusses that the prostate sits at the base of the bladder and produces seminal fluid. It grows during puberty and again around age 50. The document also covers prostate zones, blood supply, lymphatic drainage and common presentations of prostate cancer such as elevated PSA levels or urinary symptoms. Prostate cancer risk factors, diagnosis using PSA, digital rectal exam and biopsy are summarized. Staging of prostate cancer is discussed including the TNM system and Gleason grading scale.