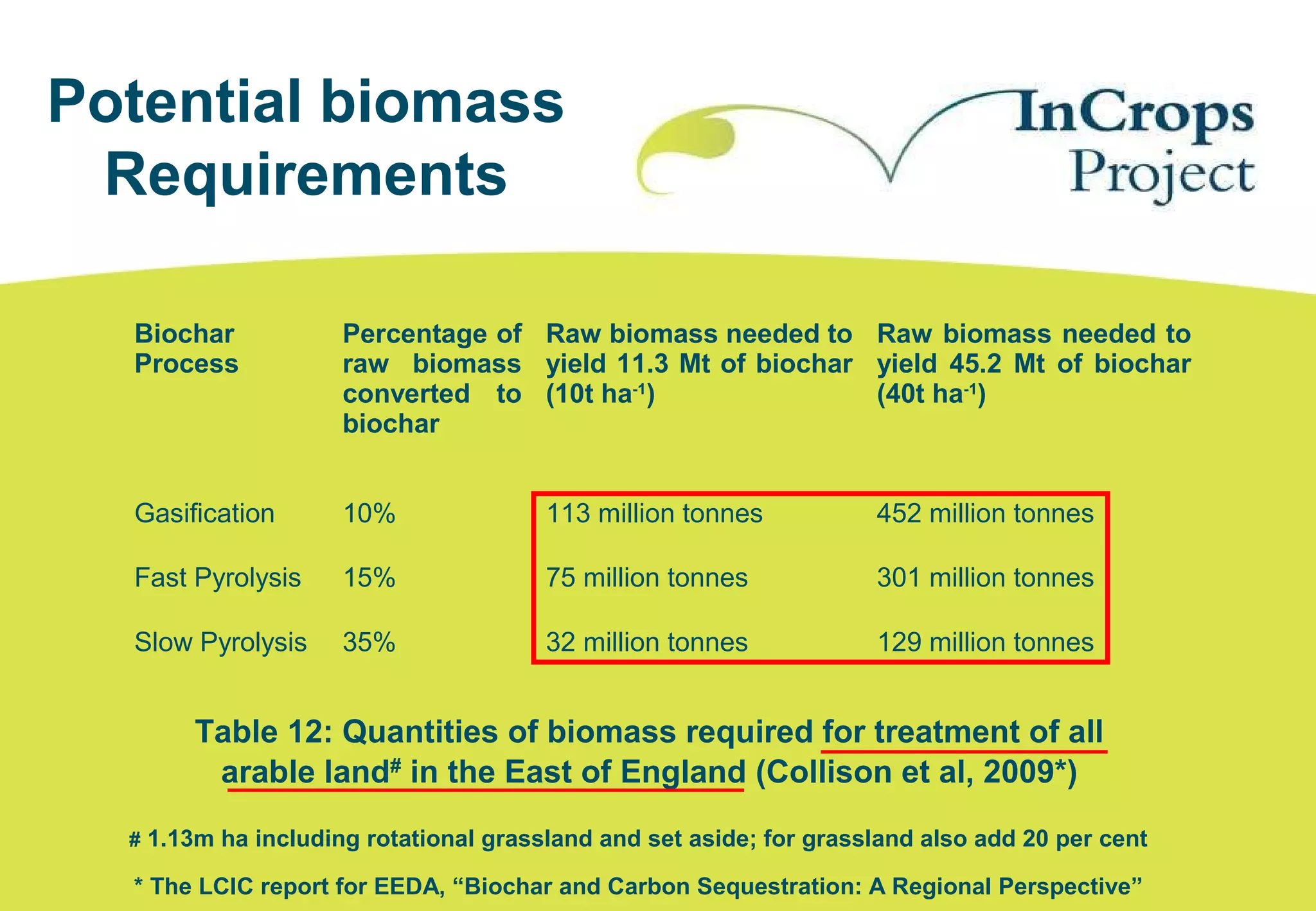

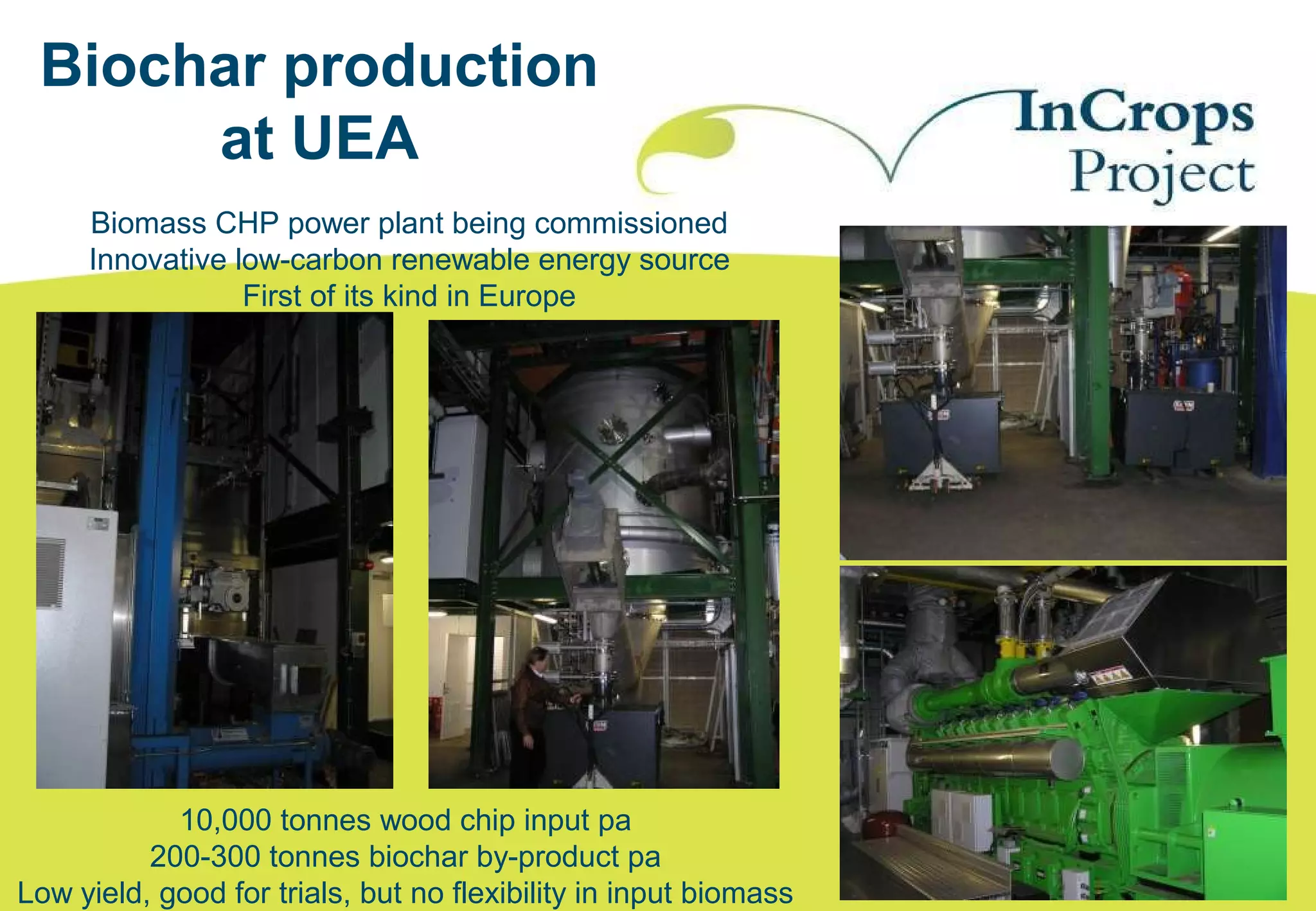

This document discusses biochar and its potential benefits for soil and the environment. It summarizes an organization called InCrops Ltd that is working to stimulate innovation in alternative crops and bio-renewable products. The document discusses how biochar can improve soil quality, productivity, and carbon sequestration. However, there are still uncertainties and a lack of commercial production. InCrops is investigating applications of biochar in the UK to identify niche markets and establish flexible low-cost production to advance scientific understanding through trials. They are working with a steering group of academics and businesses to accelerate industry adoption and innovation in biochar technologies.