This document discusses birth injuries, including definitions, risk factors, types, and descriptions of specific injuries. Some key points:

- Birth injuries occur in about 0.7% of births and account for under 2% of neonatal deaths. Factors like difficult delivery or fetal positioning can increase risk.

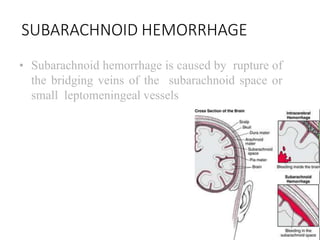

- Types of injuries include head/neck trauma, nerve injuries, fractures, and internal organ damage. Specific injuries discussed include brachial plexus injuries, skull fractures, intracranial hemorrhages, and others.

- Injuries are described in detail, along with typical presentations, diagnostic methods, and treatment approaches depending on severity. Head injuries commonly involve skull fractures or bleeding, while nerve injuries often affect the