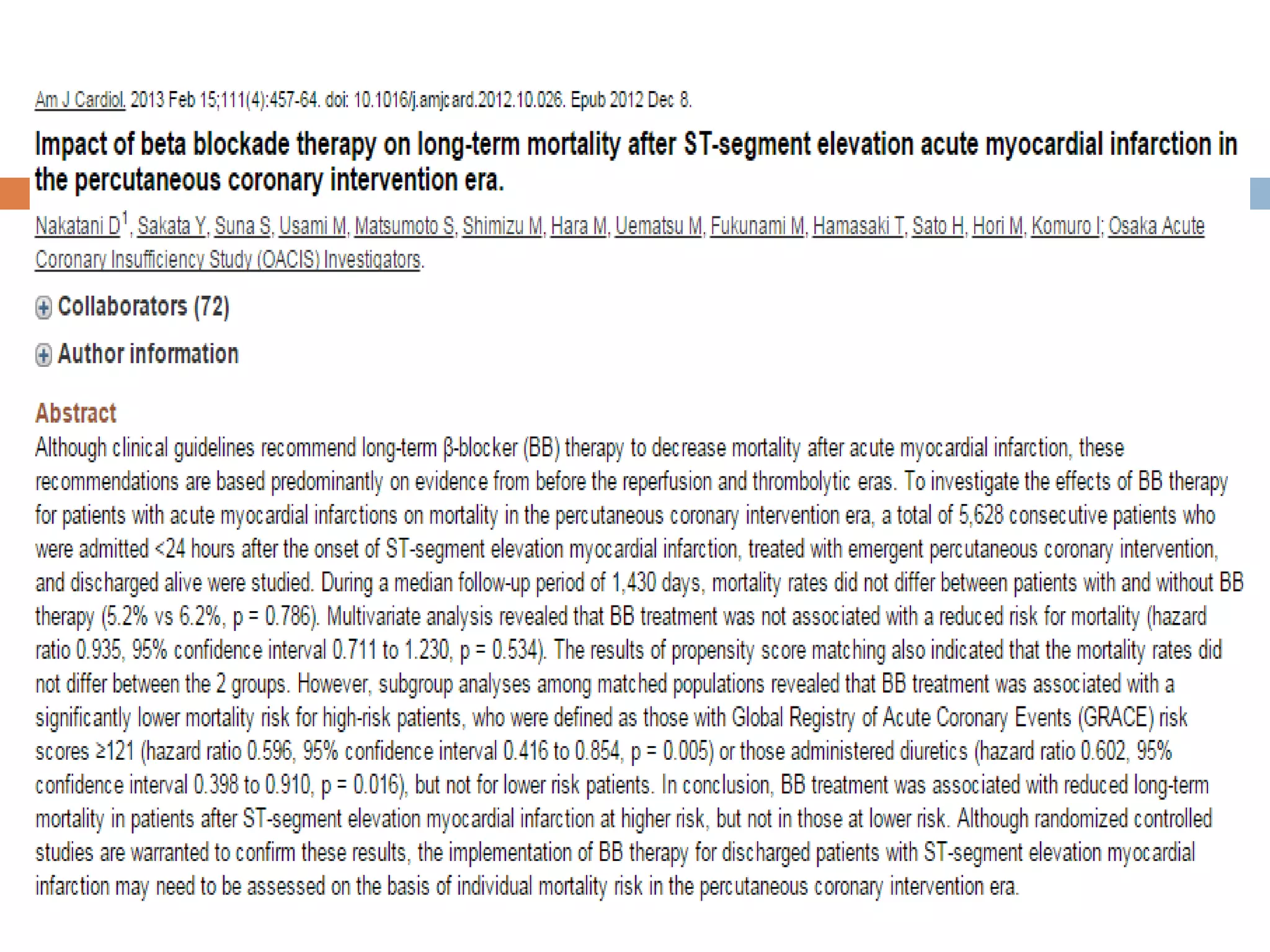

This document discusses beta blockers for acute myocardial infarction (AMI). It provides an overview of their mechanism of benefit in AMI, indications and recommendations, and evidence supporting their use. The evidence shows beta blockers reduce infarct size, mortality, and arrhythmias when started early after AMI. Intravenous initiation is generally not recommended for fibrinolytic-treated patients, but oral initiation within 24 hours is. Long-term beta blocker therapy for up to 3 years is also indicated to reduce mortality post-AMI.

![ The optimal timing of beta blocker therapy was evaluated in a study of

patients enrolled in the TIMI II trial [30]. (See "Trials of conservative versus

early invasive therapy in unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial

infarction", section on 'TIMI IIIB trial'.) A subset of 1390 patients who were

eligible for intravenous beta blockade were randomly assigned to 15 mg of

IV metoprolol tartrate (followed by oral metoprolol) or oral metoprolol begun

on day six. There was no significant difference between the two groups in

the in-hospital left ventricular ejection fraction or in mortality at 6 and 42

days. However, by day six, the early therapy group had significant

reductions in nonfatal reinfarction (16 versus 31 patients) and recurrent

ischemic episodes (107 versus 147 patients).

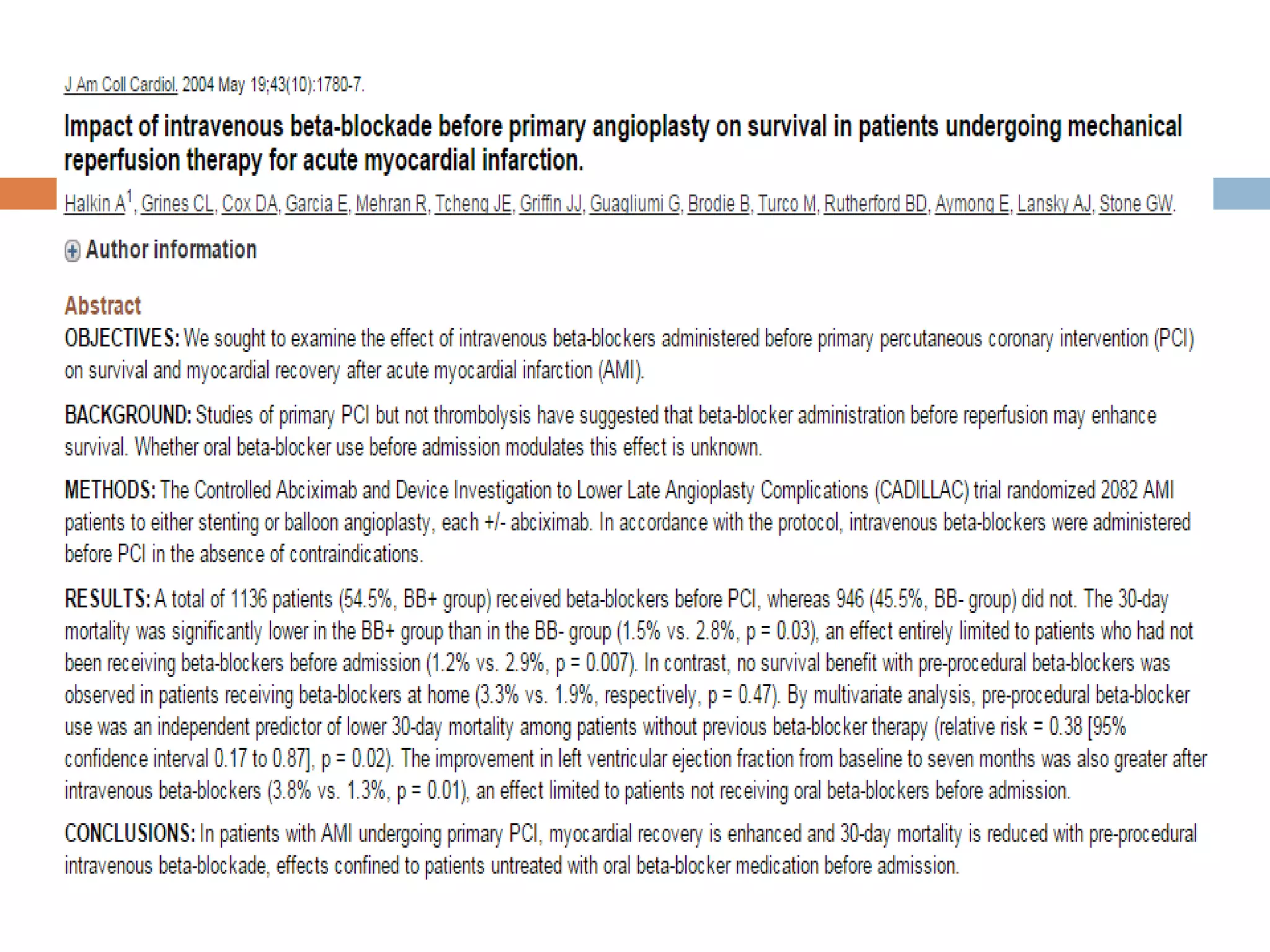

In an observational study of 2537 patients enrolled in primary angioplasty

trials, those who received beta blocker therapy before primary angioplasty,

compared to those who did not, had lower adjusted in-hospital mortality

(odds ratio [OR] 0.41, 95% CI 0.20-0.84) and nonsignificantly lower one-

year mortality (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.47-1.08). The dose and route of

administration of beta blocker was not reported.

Patients who do not receive a beta blocker during the first 24 hours

because of early contraindications should be re-evaluated for beta blocker

candidacy for subsequent therapy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/betablockers-160815130640/75/Beta-blockers-in-Acute-MI-37-2048.jpg)