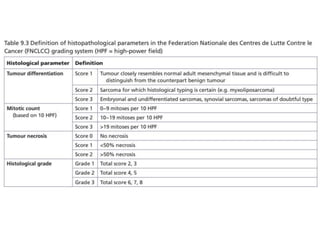

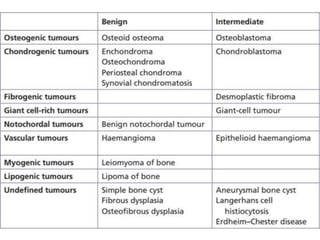

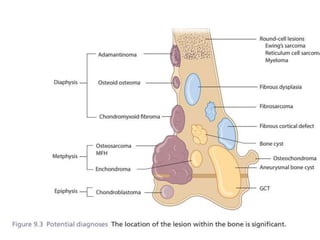

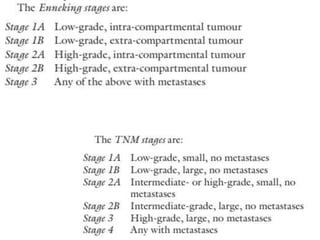

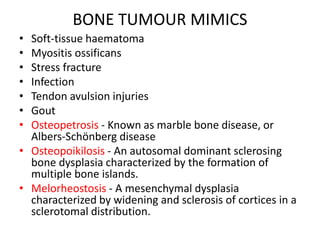

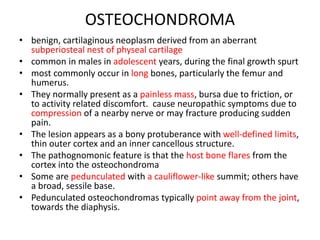

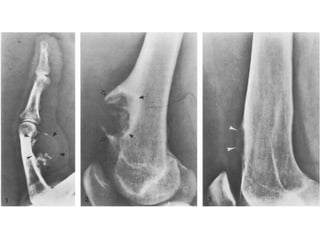

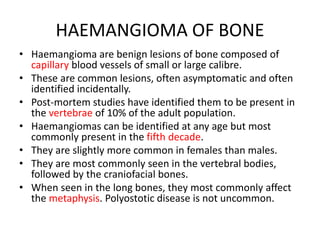

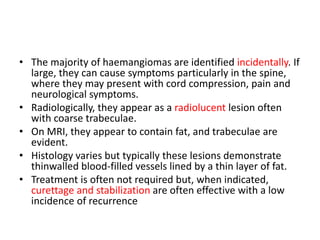

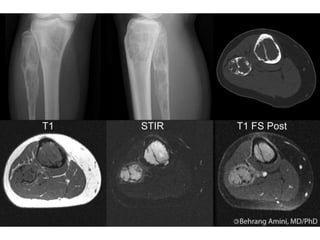

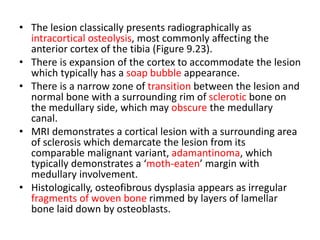

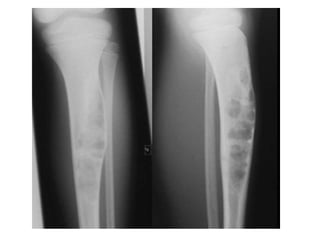

This document summarizes several types of benign bone tumors and tumor-like conditions. It describes the characteristics, presentation, diagnosis and treatment for conditions such as osteoid osteoma, enchondroma, osteochondroma, peristeal chondroma, haemangioma of bone, simple bone cyst, and fibrous dysplasia. These lesions are generally classified based on their ability to invade surrounding tissue or spread elsewhere in the body, with benign lesions not invading or spreading, intermediate lesions potentially destroying bone and recurring, and rare intermediate lesions having a potential to metastasize. Diagnosis involves imaging such as x-ray, CT, MRI and biopsy. Treatment ranges from observation to surgical resection depending on symptoms, risk of fracture