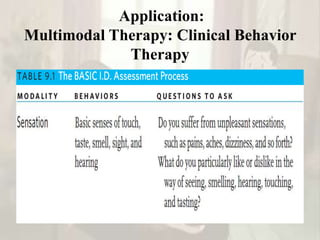

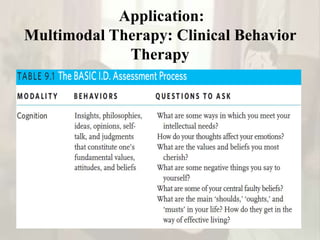

The document provides an overview of behavior therapy, including its historical background and key figures like Pavlov, Skinner, and Bandura; it discusses concepts like classical and operant conditioning, social cognitive theory, and cognitive behavior therapy; and it describes the therapeutic process in behavior therapy including the therapist's role in assessment, goal setting, and applying evidence-based techniques.