This document provides an overview of the theory of computation. It discusses the following key points:

1. Computation involves executing programs on computers to perform input-output transformations. Programs are algorithms expressed in programming languages.

2. The theory of computation classifies problems by their computability and complexity. It studies models of computation like Turing machines.

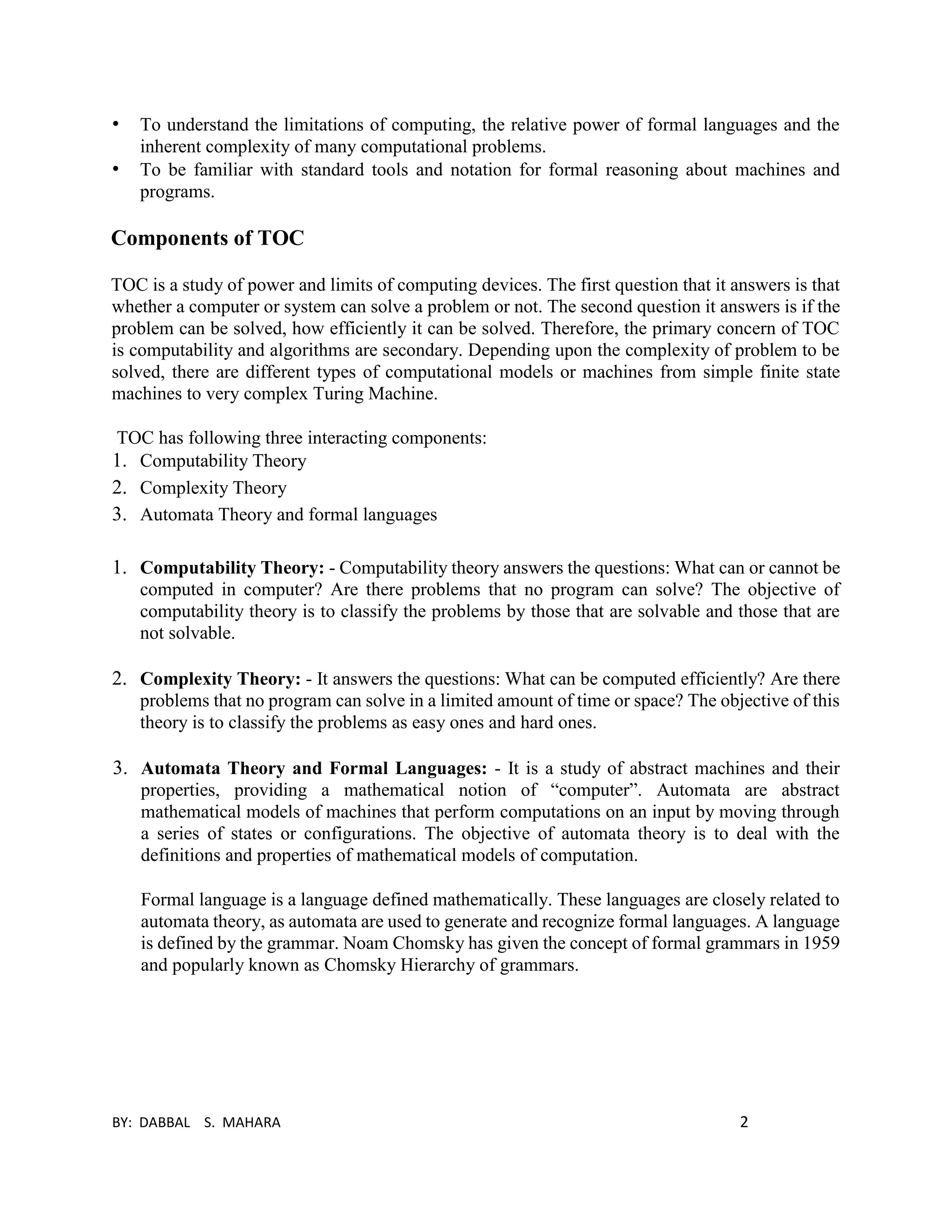

3. The theory has three main components: computability theory, complexity theory, and automata theory/formal languages.

4. Proofs in the theory use techniques like mathematical induction to show properties are true for all cases.

![BY: DABBAL S. MAHARA 3

Why Study Automata Theory?

• For software designing and checking behavior of digital circuits, verifying communication

protocols or protocols for secure exchange of information.

• For designing software for checking large body of text as a collection of web pages,

to find occurrence of words, phrases, patterns (i.e. pattern recognition, string matching etc.)

• Designing “lexical analyzer” of a compiler, that breaks input text into logical units called

“tokens

• It is a useful concept of software for natural language processing.

Abstract Model

An abstract model is a model of computer system (considered either as hardware or

software) constructed to allow a detailed and precise analysis of how the computer system works.

Such a model usually consists of input, output and operations that can be performed and so can be

thought of as a processor. E.g. an abstract machine that models a banking system can have

operations like “deposit”, “withdraw”, “transfer”, etc.

Brief History

In 1936, when no any computer were there, British mathematician, logician, computer scientist,

Alan Turing wrote a paper that defined an abstract machine called Turing Machine. It defines

power and limitation of any computational machines. The point is that whatever Turing Machines

can do, computer can do it; and whatever Turing machines cannot do, no computer can do it. In

other words, what all can be done by an algorithm; can be done by Turing machines. So, by just

studying the Turing machines, we can find power and limitations of any computers.

Later in 1940’s and 1950’s, a number of researchers introduced simple kinds of machines called

finite automata. [ See References for Chapter 2 of Textbook]

In late 1950’s the linguist N. Chomsky began the study of formal grammar that are closely related

to abstract automata.

In 1969 S. Cook extended Turing’s study of what could and what couldn’t be computed

and classified the problem as:

Decidable: The problems that can be solved by computer are called decidable. In computability

theory, an undecidable problem is a decision problem for which it is impossible to construct

a single algorithm that always leads to a correct “yes” or “no” answer- the problem is

not decidable. An undecidable problem consists of a family of instances for which a

particular yes/no answer is required, such that there is no computer program that, given any

problem instance as input, terminates and outputs the required answer after a finite number of

steps.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1basicfoundations-190509025724/75/Basic-Foundations-of-Automata-Theory-3-2048.jpg)

![BY: DABBAL S. MAHARA 7

Methods of Proofs

A proof is a convincing logical argument that a statement is true. The only way to determine the

truth or falsity of a mathematical statement is with a mathematical proof. Unfortunately, finding

proofs is not always easy. There are a number of formal proof methods in computer science.

Some of proofing techniques are as follows:

Mathematical Induction

Mathematical induction can be used to prove statements that assert that P(n) is true for all positive

integers n, where P(n) is propositional function. A proof by induction has two parts, a basis step,

where we show that P(1) is true, and an inductive step, where we show that all positive integers

k, if P(k) is true, then P(k+1) is true.

To complete inductive step of a proof using the principle of mathematical induction, we assume

that P(k) is true for an arbitrary integer k, this assumption is called inductive hypothesis and show

that under this assumption, P(k+1) must be true.

Expressed as a rule of inference, this proof technique can be stated as,

[P(1) ^ k P(k) P(k+1)] → ∀𝑛 (𝑛), when domain is the set of positive integers.

When the domain is the set of non-negative integers, so that we need to prove P(n) is true for n =

0, 1, 2,....., basis step is P(0).

Example:

Prove that if n is a positive integer, then 1 + 2 + 3 + ... + n = n(n+1)/2.

Let us prove this by induction:

Let P(n) be the proposition that the sum of the first n positive integers is n(n+1)/2. To prove P(n)

is true for n = 1,2,3...., we must show P(1) is true and that the conditional statement P(k) implies

P(k+1) is true fro k = 1,2,3...

Basis step: P(1) is true, since 1= 1(1+1)/2.

Inductive step: Let us assume that P(k) holds for arbitrary positive integer k. i.e. we assume that,

1+2+... + k = k(k+1)/2.

By using this assumption, let us show that P(k+1) is true, i.e. we show 1+2+.... + k + (k+1) =

(k+1)[(k+1)+1]/2 = (k+1)(k+2)/2.

For this, let us use P(k),

1+2+.. + k + ( k+1) = k(k+1)/2 + (k+1)

= [k(k+1)+2(k+1)]/2

= (k+1) (k+2)/2

This last equation shows that P(k+1) is true under the assumption that P(k) is true. This completes

the proof.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1basicfoundations-190509025724/75/Basic-Foundations-of-Automata-Theory-7-2048.jpg)

![BY: DABBAL S. MAHARA 11

• Suffix of a string

A string s is called a suffix of a string w if it is obtained by removing 0 or more

leading symbols in w. For example; w = abcd s = bcd is suffix of w. here s is proper

suffix if s ≠ w.

• Prefix of a string

A string s is called a prefix of a string w if it is obtained by removing 0 or more trailing symbols

of w. For example; w = abcd

s = abc is prefix of w, Here, s is proper suffix i.e. s is proper suffix if s ≠ w

• Substring

A string s is called substring of a string w if it is obtained by removing 0 or more leading or

trailing symbols in w. It is proper substring of w if s ≠ w.

If s is a string then Substr (s, i, j) is substring of s beginning at ith

position & ending at jth

position both inclusive.

• Problem

A problem is the question of deciding whether a given string is a member of some particular

language. In other words, if Σ is an alphabet & L is a language over Σ, then problem is; given

a string w in Σ*, decide whether or not w is in L.

Note: Read Chapter 1, from the textbook [ Hopcroft, Motwani and Ullman]

Formal Grammars and Languages

Grammar

A grammar is a set of rules that defines the structure of strings in the language. It specifies whether

the strings belong to the language or not. Grammars are the language generators. A language is

collection of all the valid strings that are defined by the grammar.

Formally, a grammar G is a 4-tuple (N, T, P, S), where N is a finite set of non-terminals, T is a

finite set of terminals, P is a finite set of production rules and S Є N is the start symbol.

Eg. Let grammar G = (N, T, P, S), where N = { S}, T = {a,b}, start symbol = S and P = { S

aSb , S Є }.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1basicfoundations-190509025724/75/Basic-Foundations-of-Automata-Theory-11-2048.jpg)