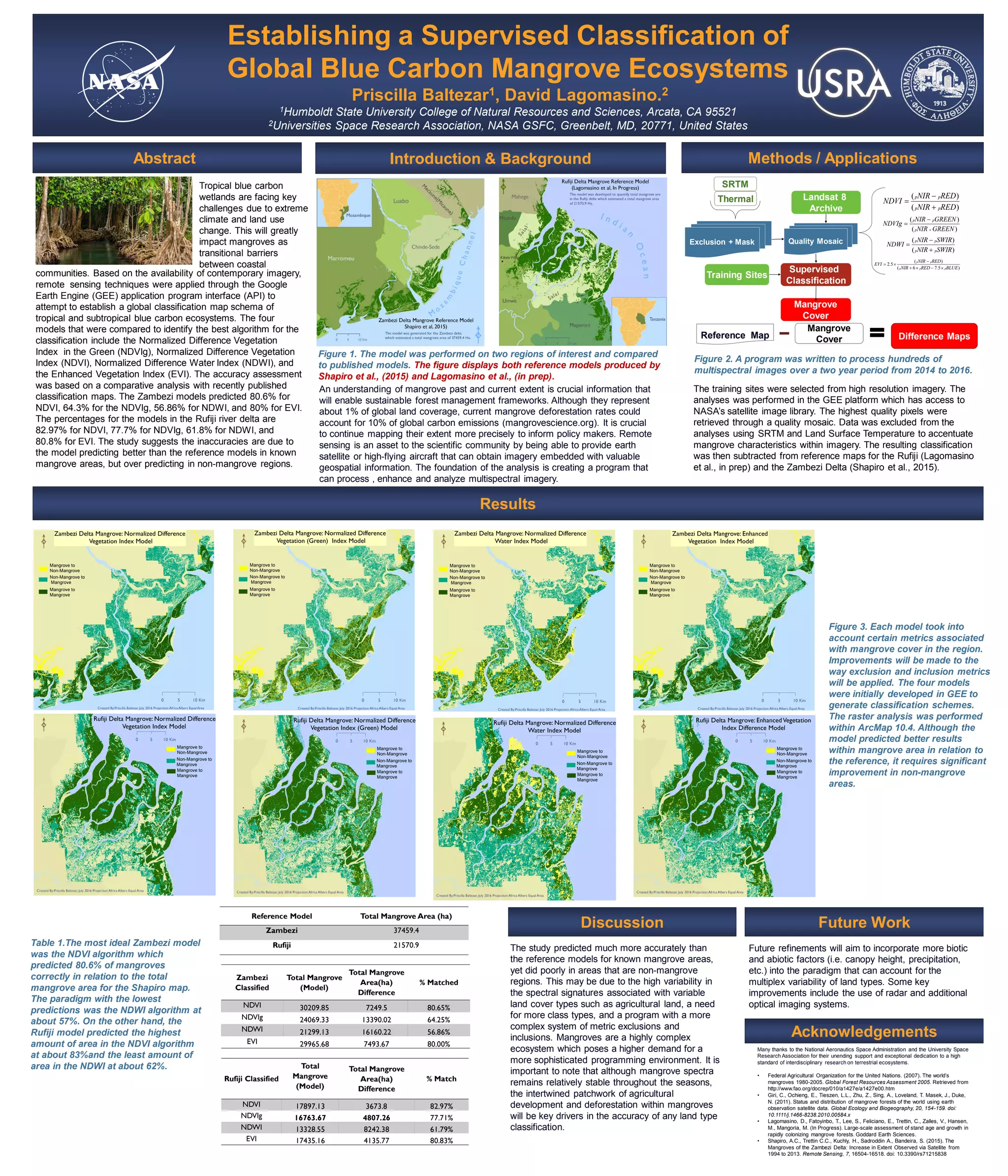

This study aimed to establish a supervised classification of global blue carbon mangrove ecosystems using remote sensing techniques. Four classification models were compared for two regions of interest: the Zambezi Delta and Rufiji River Delta. The models used different vegetation indices and were assessed against published classification maps for accuracy. The NDVI model achieved the highest accuracy for both regions at around 80-83%. However, all models overpredicted mangrove cover in non-mangrove areas, suggesting improvements are needed to better account for land cover variability. The study demonstrates the potential for remote sensing to map mangroves globally but highlights challenges in achieving high accuracy.