This document summarizes a BSc thesis that explores using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to efficiently calculate convolutions. It first provides theoretical background on direct convolution calculations and Fourier analysis. It then describes implementing a 2D convolution using the Cooley-Tukey FFT algorithm and analyzing its time complexity advantages over direct convolution. The document evaluates the implementation's correctness, benchmarks its performance against other methods, and discusses potential optimizations and improvements.

![While Fourier Analysis itself was formalized by Fourier in his study of thermodynamics in

1822 [Berg and Solevej, 2011], the result we will use of discrete Fourier transforms (DFT),

was in fact originally established by Gauss around 1805. In 1965 it was shown how to ef-

ficiently compute the DFT on problems of sizes N = 2m by Cooley-Tukey [Duhamel and

Vetterli, 1990] with what is now widely known as the Cooley-Tukey Radix-2 algorithm,

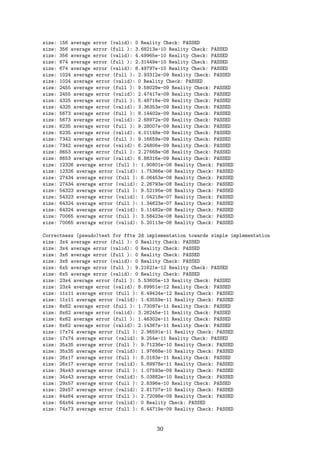

one of the first of many Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT). With a computational complexity

of O(N lg N), with lg N being the base-2 logarithm of N, the algorithm opens up convolu-

tions to vastly larger problem sizes.

As well for this project is the hope for an efficient implementation of a convolution function

for use in the SHARK Machine Learning C++ library [Igel et al., 2008]. The SHARK library,

having a wide array of machine learning algorithms implemented, is presently lacking the

support for performing fast convolutions on signal data, making this project of direct and

immediate use.

From a theoretical point, the difference between solving the convolution problem using FFT

on one, two or n-dimensional data is arbitrary, I will however, focus mainly on implementing

and explaining the case of the 2D convolution using FFT. In addition, most of the work will

lie in explaining and implementing the Cooley-Tukey Radix-2 algorithm. A primary reason

for choosing this algorithm in particular is that its presentation was a breakthrough in per-

forming fast discrete Fourier transforms, this algorithm also dips into some of the advanced

index mappings needed, without getting too tedious and confusing.

Finally, I will assess correctness of the implementation and give estimates of the error on real

world data. I will also perform benchmarking and compare the results with benchmarking

results from the widely used tool Matlab and and implementation using the FFTW library for

solving the FFT.

Throughout this BSc thesis, I will use the terms signal and image interchangeably referring

to a discrete function which in practice is just an array of input data. Moreover N and M

will often without definition refer to arbitrary dimensions of input data and the size refers to

the total size of the input data, i.e. Size = MN. Likewise, K will refer to the dimension(s)

of a K or K×K vector or square matrix called the kernel.

2 Theoretical Foundation

2.1 Direct Convolution

A convolution is a mathematical operation on two functions f and g resulting in a new

function denoted f ∗g. The convolution operation has many practical applications. In image

processing for instance, the function g could represent an image, and the function f a weight

function known as a kernel. The kernel could in turn represent some filter or transformation

on the image such as a bloom filter or simply a translation or scaling. The convolution on

continuous functions f, g is defined by

(f ∗ g)(x) =

∞

−∞

f(t)g(x − t) dt .

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-4-320.jpg)

![In many areas of use, we are often presented with discrete data 1. A discrete version of the

convolution and its two-dimensional counterpart is defined as

(f ∗ g)[x] =

∞

k=−∞

f[k]g[x − k] .

(f ∗ g)[x, y] =

∞

k=−∞

∞

m=−∞

f[k, m]g[x − t, y − m] .

Note that even thought the functions can theoretically extend to infinity, in practice the func-

tions will often be assumed zero-valued outside some bound. In case of image processing,

the bounds is simply the image and filter size. If we assume zero outside the bounds, con-

volved values near the edge will contain irregularities (also known as edge artifacts) since

not all values computed were based on actual image pixels. We therefore define the valid

region as the output region computed exclusively from values inside the bounds.

Assuming zero outside the boundary reduces the sums to

(f ∗ g)[x] =

b

k=a

f[k]g[x − k] ,

where we, in context of the computer, choose to set a = 0 whereto it follows that b = K − 1

for K the kernel array size.

The above method for computing the convolution is called the direct method, whereas using

Fourier Transforms to perform the convolution is called an indirect convolution [Sundarara-

jan, 2001]. When we introduce the convolution in terms of the Fourier transformation, the

convolution will be assumed periodic, meaning for a function defined on n points, for every

point, f[x] = f[x + n]. This is fundamental to Fourier transformation, since the theory at the

root of Fourier Analysis requires the functions to have a period. Due to this, we will see edge

artifact appear near the edges due to the convolution sum doing a wraparound catching val-

ues from the other end of the signal. This is of little concern in practice as we simply extend

function by desired values to a size of N +K −1, in effect extending the period to N +K −1

as well. To see why this works we examine the boundary case x = 0 where k = K − 1. Since

the sum in the convolution goes from 0 to K − 1 we get

f[k]g[x − k] = f[K − 1]g[−(K − 1)]

= f[K − 1]g[N + K − 1 − (K − 1)] (Period N + K − 1)

= f[K − 1]g[N] ,

where we note that g[N] is placed safely in the area of our constructed values. Subtracting

one from every index of g in the above calculations shows the same is true in the boundary

case g[N − 1].

It is often necessary to assume the kernel has what is called a kernel center (sometimes

kernel anchor). The center can be seen as the special case in the sum, in which the signal

input, multiplied by the kernel center, is placed back at the same index. This does not happen

in general. For instance, if we want the result of the convolution to be the sum of every value

with its neighboring values we can apply the one-dimensional filter [1, 1, 1] to the signal. If

the signal is [0, −1, 3, 0, 0], we want the result to be [−1, 2, 2, 3, 0] but from the definition

alone we get [0 + 0 + 0, −1 + 0 + 0, 3 − 1 + 0, 0 + 3 − 1, 0 + 0 + 3] = [0, −1, 2, 2, 3]. Since

1

data is only defined on a (possibly infinite) number of points

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-5-320.jpg)

![the convolution has no center by definition, this abstraction is one we create and maintain

ourself. Define kc as the kernel center. When performing the convolution (f ∗ g)[x] for some

x, at some point in the sum, the product f[kc]g[x−kc] appears with signal values originating

from x − kc. In other words, if the kernel center is placed at index kc. The wanted result

will have values shifted in the positive direction by kc. This is a small detail relevant only to

implementation.

2.2 Fourier Transformation

2.2.1 Fourier Series

Before we introduce the Fourier Transformation, it is instructive to introduce the Fourier

Series. In solving the heat-equation2 Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier (1768-1830) founded

Harmonic Analysis. Fourier showed that any periodic functions can be described as an infi-

nite sum of sine and cosine functions. It’s worth giving this some thought, as this is neither

a trivial or intuitive result at first, it’s actually quite remarkable. Even without delving into

the theory of why this is true, some intuition for the Fourier transform is granted.

Let f(x) be a periodic function with period P. If we adapt the notation of the complex

exponential cos(2πnx/P) + i sin(2πnx/P) = e2iπnx/P = W−nx

P , the function f(x) can be

described exactly by the Fourier series

f(x) =

∞

n=−∞

cnW−nx

P ,

where the coefficients cn is given by

cn =

1

P

x0+P

x0

f(x)Wnx

P .

This opens up the possibility of describing the function f, not by its values f(x) in the spatial

domain, but by its frequency components cn instead. When we talk about representing a

function in the frequency domain, these are the values we talk about.

2.2.2 Discrete Fourier Transform

Until now we have talked almost exclusively in terms of functions f. For discrete functions,

it is sometimes notationally helpful to simply use xn = f[n] and to treat the values as a

sequence.

On a sequence of values x0, x1, . . . , xN−1, we define the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) F

as the sequence of values X0, X1, . . . , XN−1 given by:

F{xn} =

N−1

k=0

xkWkn

N = Xn .

Notice the resemblance with the definition of the frequency coefficients of the Fourier Series.

The integral simply reduces to a sum. By tradition, the factor of 1/N (1/P in the continuous

case), is removed. This has no consequences until when we want to perform the inverse

transformation, transforming the frequency components into values in the spatial domain

again. We could have let the transform have the factor of 1/N, and then let the inverse

transform be without it. The same is true for the factor of −1 in the exponent as should

2

Differential equation describing how heat moves through a metal plate

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-6-320.jpg)

![2.2.4 Convolution Theorem

The motivation for going through so much trouble of talking frequencies and transformations

has so far only been remarked briefly, so it’s a perfect time to introduce the convolution

theorem, which is the one central result used in every computation of the convolution using

Fourier Transformation, and therefore central to this project.

Theorem 2.1 (Convolution Theorem) For two discrete periodic functions f and g with equal

period, the following is true

F {f ∗ g} = F {f} · F {g} , (2.1)

and equally

(f ∗ g)[n] = F−1

{F {f} [n] · F {g} [n]} . (2.2)

Before proving the convolution theorem, it’s worth discussing what this means in our case,

and under what restrictions. Firstly, instead of convolving the two functions directly by

calculating a sum for each value, we end up with a single multiplication. As we want the

convolution theorem to be applicable, we need the two convolving functions to have the

same period. When performing convolution using the direct method, we need only multiply

the numbers inside the range as we assume zero values outside the bounds, which therefore

contributes nothing. Conversely, when performing the convolution using the convolution

theorem we will need to extend the kernel to the size of the signal.

Proof This proof uses the same trick we used when proving F−1 was the inverse of F that

reduced a sum of complex exponential to a single non-zero case. We start with the definition

of the convolution, and insert the inverse of the transform F−1{F{f}} = f in place of both

functions. For convenience we define F{f} = F and F{g} = G. We get the following:

(f ∗ g)[m] =

N−1

k=0

f[k]g[m − k]

=

N−1

k=0

N−1

n=0

1

N

F[n]W

−nk

N

N−1

l=0

1

N

G[l]W

−l(m−k)

N

=

1

N

N−1

n=0

F[n]

N−1

l=0

G[l]

1

N

N−1

k=0

W

−nk

N W

−l(m−k)

N

=

1

N

N−1

n=0

F[n]

N−1

l=0

G[l]W

−lm

N

1

N

N−1

k=0

W

k(l−n)

N .

With similar arguments as in the proof of the inverse. If n = l the sum over k becomes N,

and reduces to zero in all other cases. Thus the sum over l collapses to the case l = n and

we get:

1

N

N−1

n=0

F[n]

N−1

l=0

G[l]W

−lm

N

1

N

N−1

k=0

W

k(l−n)

N =

1

N

N−1

n=0

F[n] · G[n]W

−nm

N

1

N

N

= F−1

{F[n] · G[n]} .

This ends the proof.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-8-320.jpg)

![2.2.5 Fast Fourier Transform: Cooley-Tukey Radix-2 algorithm

The same year as the Programma 101, the first Desktop Personal Computer went into produc-

tion, Cooley and Tukey published a short paper detailing how the Discrete transformation

problem of size N = 2n, can be solved efficiently[Duhamel and Vetterli, 1990]. The idea

is to restate the problem recursively in terms of two subproblems of half the size occurring

when splitting the input in even and odd indices. We will here use notation FN to explicitly

state the size of the input sequence of the transform. The derivation goes as follows:

FN {xk} =

N−1

n=0

xnWkn

N

=

n even

xnWkn

N +

n odd

xnWkn

N

=

N/2−1

m=0

x2mW2km

N +

N/2−1

m=0

x2m+1W

k(2m+1)

N

=

N/2−1

m=0

x2mW2km

N + Wk

N

N/2−1

m=0

x2m+1W2km

N .

Renaming ym = x2m and zm = x2m+1, letting M = N/2 and rewriting the exponent to

reflect the new problem size

W2km

N = e−4πkm/N

= e

−2πkm

N/2 = Wkm

N/2 = Wkm

M ,

we end up having two DFTs of half the size

M−1

m=0

ymWkm

M + Wk

N

M−1

m=0

zmWkm

M = FM {yk} + Wk

N · FM {zk} .

The factor Wk

N is called a twiddle factor and is the only complex exponential needing to be

calculated in practice since in the base case N = 1 we simply get

F1{xk} =

0

n=0

xnWkn

N = x0W0

1 = x0 .

With analogous derivation, since 1/N = 1/2 · 1/M, the inverse becomes

F−1

N {xn} =

1

2

1

M

M−1

m=0

ymW−km

M + W−k

N

1

M

M−1

m=0

zmW−km

M (2.3)

=

1

2

F−1

M {yk} + W−k

N · F−1

M {zk} . (2.4)

This can be recognized as a classic divide and conquer approach. We gain some simplicity

by how neatly the new subproblems shrink until the absolutely trivial base case solves itself.

However, we gain a great bit of complexity due to the non-trivial index mapping required as

a result of the splitting of even and odd indices repeatedly. This will be addressed in 4.1.

Another consequence of this way of splitting is the possibility to reuse reoccurring twid-

dle factors. This will be explored further in 4.2. Also to be noted is the occurrence of a

great number of so called free complex multiplications. Free multiplications are multipli-

cation of any complex number by +1, −i, −1, +i that happens at each recursive step when

k is 0, N/4, (2N)/4 and (3N)/4 respectively. The exception is N = 2 where we only have

multiplication by +1 and −1. This was not exploited in the project due to time constraints.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-9-320.jpg)

![2.2.6 Alternative methods and implementations

James W. Cooley and John Tukey made a breakthrough with their presentation of the Radix-

2 divide and conquer algorithm, but other methods has since been presented, some with

great success as well. Winograd, for instance, managed to reduce the number of arithmetic

computations using convolutions. Given the goal of this project, this should come as a bit

of a surprise. However, implementations of this method has been disappointing and the

emergence of so called mixed-radix and split-radix algorithms took the scene[Duhamel and

Vetterli, 1990]. The split-radix algorithm resembles the radix-2 approach greatly. Like the

Cooley-Tukey algorithm, the split-radix algorithm divide the input problem into subproblems

of smaller size, but instead of just dividing into two problems of equal size, the problem is

now divided into 3 subproblems, one at half size and two at a quarter the size of the origi-

nal problem. This happens to open up the possibility of performing a higher degree of free

complex multiplications.

The Cooley-Tukey algorithm has also been generalized to any problem size N that can be

factored N = N1N2. This is the aforementioned method named the mixed-radix method

[Frigo and Johnson, 2005]. The index mapping is now instead k = k1 + k2N1 and n =

n1N + n2 and the complete formula needing to be computed is

Xk1+k2N1 =

N2−1

n2=0

N1−1

n1=0

xn1N2+n2 Wn1k1

N1

Wn2k1

N Wn2k2

N2

.

This is effectively making a DFT of size N into a 2D DFT of size N1 × N2. It is not at all

clear why this way of rewriting actually reduces the number of operations, but it’s due to

the reuse of the smaller DFTs. This is what we do in the Cooley-Tukey Radix-2 algorithm as

well having just two DFTs of half the size. We know a DFT of size N has worst case time

complexity in the order of N2 operations by use of the definition. Using this index mapping,

the inner sum are DFTs of size N1. These are each computed a total of N2 times and then

reused to calculate the N values of the original DFT. The outer sum of length N2 is computed

for each N values. In total we get:

T(N) = NN2 + N2N2

1 = N1N2

2 + N2N2

1 = N1N2 (N1 + N2) .

For N1, N2 > 2 this is less than N2[Duhamel and Vetterli, 1990].

One of the most, if not the most, successful FFT library, FFTW, tailors the execution of the

transform to the specific computer architecture it runs on by use of an adaptive method. In

effect, the FFTW implementation is composed of various highly optimized and interchange-

able code snippets (codelets), of which they benchmark the efficiency, during computation,

and switches based on the measurements[Frigo and Johnson, 1998]. An implementation

of this will not be done due to time constraints. Instead, an alternative implementation of

the convolution solver, where the transforms are performed by use of the FFTW library, is

implemented alongside. Since the FFTW library supports precomputation of transformation

plans based on execution time measurements, I have implemented functionality to create a

convolution plan in case multiple convolutions of equal size is needed. This serves as an top

layer interface for the FFTW planning code. A tutorial detailing the use of the implemented

convolution functions using FFTW can be found in the appendix B.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-10-320.jpg)

![4.1 In-place calculations and bit-reversal

The input data type is, as with most in the SHARK library, assumed to be real. Since the

fourier transformation produces complex numbers, the closest we can get to a complete in-

place calculations are to copy once from real to complex, and then back when done. This is

indeed possible, while not entirely trivial to see why since each recursive step of the divide

and conquer algorithm splits the data in a way that seems intuitively like opening a zipper.

This operation however, has a well defined structure as I will show in the following.

To systematically assert the index mapping at each isolated recursion level, observe the fol-

lowing function:

s(x) =

x

2 : x even

x+N−1

2 : x odd

.

The function s(x) is a permutation of the set B = [0, 1, . . . , N − 1] with N = 2m for m ∈ N,

and represents the index mapping of a single step of the recursion in the Cooley-Tukey Radix-

2 algorithm. It happens that s(x) is also what occurs in a cyclic right shift on bit-strings of

length m. To see this we need only remind the reader what happens in a cyclic right shift.

For a number x, if the least significant bit is 0, x is even and the now ordinary right shift

simply halves x. If the least significant bit is 1, x is odd, and the least significant bit becomes

the most significant. In effect, the process can be seen as subtracting the least significant bit,

divide by two, and adding 2m−1, thus we get s(x) = (x − 1)/2 + 2m−1 = (x − 1)/2 + n/2 =

(x + N − 1)/2 which is the odd case of s(x).

Definition 4.1 (Bit-reversal) Define the bit reversal of a bit string bm−1bm−2 . . . b0 of length

m, as the bit string b0b1 . . . bm−1 with bits placed in reverse order such that bit bi is placed at

index m − 1 − i.

Theorem 4.1 Recursively splitting an array of length N = 2m into two evenly sized arrays

with even numbers in the first and odd numbers in the second can be done in-place by complete

bit-reversal of the original index i ∈ [0, 1, . . . , N − 1].

Proof At each recursive step j ∈ [1, . . . , m] the splitting is equivalent to a circular right-shift

of the m − j − 1 rightmost bits while not touching the j − 1 first. Thus at the end of the j’th

split, the j first bits are placed correctly. The recursion terminates in the trivial case when

there’s only one bit remaining, and a circular right-shift alters nothing. Since any bit bi is

right-shifted i times before it at the (i+1)’th step is placed at index m−(i+1) = m−1−i, the

entire bit-string ends up being reversed. Thus by definition of the Bit-reversal, recursively

splitting in even and odd of the sub-arrays is equivalent to reversing the entire bit-string.

In the case of the case of Cooley-Tukey, it is not needed (or efficient for that matter) to per-

form a dividing operation at each recursive step. Instead, reordering the entries beforehand,

into the indices given by the reversed bit string of the indices is sufficient. The output will

be placed correctly when the algorithm finishes. As a side note, this procedure could have

been done by index mapping instead. Two problems then arise. Firstly, it turns out not to be

a trivial task to have input placed correctly in the end. Usually you will have them placed in

a manner comparable to the bit-reversed order. Secondly, this may in fact slow computation

due to inefficient memory placement. In truth, many different methods for reordering has

been proposed, many doing so during computation. As to which one is faster may depend

on the particular hardware used in the computation [Frigo and Johnson, 2005].

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-12-320.jpg)

![estimated time consumption of the direct method by plugging NMK2 into the linear model.

For the linear model arising from the indirect method we need to undo the transformation.

Let z be the zero-padded size of the input, t the execution time and T(x) the transformation

with T−1(x) = x lg x, we have:

T(t) = mz + c

t = T−1

(mz + c)

= (mz + c) lg(mz + c) .

As noted, one big difficulty is the relative nature of the error when benchmarking. In practice

a great relative inaccuracy is seen for smaller input when minimizing the squared difference.

A solution is to use the following linear modeling scheme. Let (xi, yi) be measured data

points. We want to approximate the data by a predicting function ˆyi = mxi + c to not

minimize the squared difference as is usually done, but minimize the squared relative error

n

i ((xi − ˆyi)/xi)2. The complete derivation was performed and can be found in appendix C,

but in short we compute m and c by

m =

n

i=1

n

j=1

xj−xi

y2

i yj

n

i=1

n

j=1

x2

j −xixj

y2

i y2

j

, c =

n

i=1

1

yi

− m · n

i=1

xi

y2

i

n

i=1

1

y2

i

.

As noted by [Frigo and Johnson, 1998], there’s a great difference between which operations

during computation are faster using different computer architectures. This means that what

I conclude during this project may not yield optimal results on other architectures. It is

however possible to automate some estimation, effectively carrying out the steps above on

the system it is used on, in an effort to choose the optimal signal sizes to switch. This will not

be explored during this project, mainly due to how measuring execution time is OS specific,

and thus a bit out-of-scope.

5 Implementation

5.1 Cooley-Tukey Radix-2

In short, the implementation requires the input signal and kernel to be transformed using

FFT, multiplied element-wise, and the result transformed back. The code has primarily been

broken into two functions, one for performing the convolution, and one for the FFT and the

its inverse.

A flow chart of the convolution program can be seen in figure 1. The convolution function,

based on the requested boundary mode, determines how much zero-padding is needed and

then create the needed data structures for storing the complex numbers used during trans-

formation and in the frequency domain. Since the two FFT’s are needed at the same time,

an attempt to spawn a child thread for carrying out one FFT is done. To not require the user

to use C++11, this is done using pthread. A simple data structure for a carrying parameters,

and a wrapper function has been written to not put requirements on the implementation of

the FFT function. Given the results of the transforms, the convolution function multiplies the

values element-wise, performs an inverse FFT and copies the resulting values back into the

given output data structure indexing in accordance with kernel center and boundary mode.

The implemented FFT function, carrying the majority of the complexity in the implementa-

tion, works as follows. First the data is copied into the given output data structure using

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-15-320.jpg)

![bit-reversed indexing. Then the twiddle factors are precomputed. After that, a four times

nested for-loops carries out the 1D recursion on the rows in which the following happens:

1. For every row

2. for every recursive level starting with N/2 subproblems of size 2.

3. for every subproblem of the current size (2, 4, 8, . . . )

4. for every element in the current subproblem, multiply the required values and twiddle

factors, and save them accordingly to fit the next subproblem size of double size.

By this time we reorder the input again using bit-reversal preparing 1D FFT’s on the columns,

but instead of performing the calculations on the columns, we transpose the input and per-

form the transformations on the rows again. As these computations are completed, the

function call terminates.

5.2 FFTW

Since results were not what was hoped for, an effort to make an implementation using the

FFTW library has been created alongside for both one, two and three dimensional input data

as well. To use the FFTW library, it is required to create both input and output arrays, since

in-place calculations is not possible for larger input sizes using FFTW [FFTW-Docs]. To save

memory use, three auxiliary arrays are made instead of two for both signal and kernel, and

the FFT results are juggled around to only overwrite already used data.

Since FFTW uses precomputed plans to optimize computations, an interface for performing

convolution utilizing this feature has been written as well. This is an optional step which is

advisable only in the case many convolutions of the same size input is needed. Using a plan

also gave the possibility to store a transformed kernel for reuse in case the same kernel is

needed in multiple convolutions. The specific details on the use of this implementation can

be found in appendix B.

6 Empirical evaluation & experimental setup

To systematically test the written program, a number of tests has been created and suitable

data chosen to best assert the success of different formulated goals. I have chosen to use

the well known Lena image shown in figure 2, for most testing and benchmarking purposes,

sliced or extended to needed sizes. This image is often used for comparing results between

different image processing algorithms. Here, the choice is a little bit arbitrary, since we do

not need to resort to a qualitative measure for the convolution method. Either it works or it

doesn’t, and the error can be measured at round-off level, making the testing entirely quan-

titative. For this reason, special input data, of which the outcome is known by analytical

means, has been used as well. When benchmarking the implementation I will be using CPU

time measurements in most cases. The reason for this is two-fold. Firstly, I’d like to factor

out the unknowns of operating systems CPU scheduling to give a more general measure, and

secondly, this seems to be the way benchmarking is often done other places (as in Matlab).

This in turn helps to compare results.

To cover the widest range of sizes of input data, the problem sizes used in testing are set to

increase exponentially by a real exponent by either 1.5 or 2, and then floored to an integer.

Unless otherwise stated, each data point in each test is generated from an average of 25

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-17-320.jpg)

![Figure 2: Lena, the primary test image of use.

repetitions of that particular problem size.

All tests were done on an Intel Core 4x2 50Ghz i7-4710MQ. The testing goals are, and

will be tested, as follows:

• Correctness & error estimation: As mentioned previously, the error should be low.

Due to round-off errors, some error in the calculations is to be expected. An IEEE

754 double-precision floating point numbers has 52 bits for representing the fractional

part of the number. Since we get an extra bit of precision due to the first digit being

represented implicitly4, the error can thus at most be the difference in the last digits5

2−53 = 10−15.955. While it is theoretically possible to formally derive bounds on the

propagating error, the error is tightly connected to both the relative and absolute size

of the numbers. I therefore expect a result with too large an upper bound on the error

when compared to what is both acceptable and realistic. Previous work suggest the

error in general for different FFT methods increases as a factor of

√

N on average

where N is the input size [Duhamel and Vetterli, 1990]. Thus we should expect and

error of about

10−15.955

·

√

20402 ≈ 10−13

,

on average for the biggest input being transformed. Since every output value from the

convolution has passed two transforms, the error as a result of the convolution should

be around 10−10. As well as the average error, the maximum error is observed. This

is primarily to ensure no single significant error is hiding under a low average error.

These could come from boundary case errors for instance.

Using constructed M ×N input data such that the value at index (i, j) is i+j, and using

a 3 × 3 kernel with center (1, 1) and values 1/4 at indices {(0, 1), (1, 0), (2, 1), (1, 2)}

while leaving the rest zero, should return the input data as output in the valid region.

The upper edge (j = 0) should, except for corner pieces, have the convolved value

4

The fractional number is represented in a such way that the first bit is always one, and can therefore be

represented implicitly.

5

This is actually only true under the assumption that the exponent is 1.

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-18-320.jpg)

![7.5.4 Switching mechanism

Firstly, the switching mechanism seems to work. Secondly, considering that the input varies

quite a bit, and since hitting the exact crossover point between methods is practically impos-

sible due to random variations in the execution time. An error of less than 5% of the tested

input is quite respectable. That said, it’s hard to argue what is good. The particular input

sizes where the method has a tendency to choose the wrong method may be input sizes that

are used often in practice, or may not be used at all. It is most likely that the error happens

in areas where theres a crossover point. This could explain the grouping we see. In that

case, the difference in time used by either of the methods shouldn’t be too big, and choosing

the wrong method at these points is therefore of less concern as well.

7.5.5 Possible improvements

As noted already, complex multiplications with +1, −1, +i, −i can be regarded as free, and

since I did not exploit this, this is a simple way to reduce execution time. Using only features

from C, and thus skipping the overhead that comes along with C++ should, in the case of an

algorithm like this, yield substantially better results. If we instead wanted to save the mem-

ory use, one way is to only allocate space for the complex numbers, and then use the given

array for the real part of the number, thus getting closer to in-place calculations, but since

the two arrays is now not placed efficiently in memory, this is expected to slow computations

greatly. Alternatively, one could make assumptions on the input data, and assume the data

is already stored in an efficient complex data structure. However, this would violate a goal

in this project, to write a general-purpose implementation, and for that reason fit less in the

context of the SHARK library. I would therefore advice against any of these solutions.

When it comes to the FFTW library, its adaptive nature should resist most attempts to per-

form FFT faster using only a single FFT algorithm. If instead we went for a more realistic

goal just to have an implementation comparable to FFTW and Matlab, I would argue the di-

rection to take would be first to rewrite the code in a low level language such as C. Look

into ensuring memory allocation is efficient and thereafter take a look into implementing the

optimization I have done so far, and adjust it further by previously mentioned optimizations

while looking into even more ways to reduce the number of simple operations. Perhaps

even implementing the split-radix algorithm with the savings in operations count that fol-

lows along, and a mixed-radix implementation would remove most needs for zero-padding.

Doing small optimizations can seem like beating a dead horse, but as noted in [Frigo and

Johnson, 1998], FFT implementations consist of a large number of the same small opera-

tions, meaning a small increases in efficiency on these small operations often leads to great

gain in performance for the entire implementation. And in that regard, the Cooley-Tukey

Radix-2 implementation in this project may in fact be nearly comparable to other implemen-

tations.

8 Conclusions and Outlook

In this BSc thesis, I have shown how the Discrete Fourier Transform, through the convolu-

tion theorem, presents us with an indirect way to perform the convolution operation. I have

shown how it allows for reductions in computational complexity due to FFT algorithms re-

ducing the computational complexity to an order of O(n lg n) as opposed to the polynomial

O(n2).

During the project, an implementation of an indirect convolution method using the Cooley-

Tukey Radix-2 algorithm has been implemented with varying success. I conclude that the

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b1839bd1-2a78-4db3-9b3a-8259e67581a5-151102083036-lva1-app6892/85/bachelors_thesis_stephensen1987-27-320.jpg)